April 15–May 28, 2011

Zurich’s art world was more-than-ordinarily abuzz when Peter Kilchmann and Eva Presenhuber unveiled new gallery spaces on the 14th April. Both have moved a few hundred meters north-west to the Diagonal building at the base of Switzerland’s new tallest building, away from the Löwenbräu-Areal brewery where they had previously lived alongside the Kunsthalle, Migros Museum, and other colleagues. The brewery’s cultural residents had once been moved in by city authorities to catalyse improvement in the neighborhood. Now Presenhuber and Kilchmann are the cherries on the cake of yet another transformation project, only this time it’s the Maag Areal, where mechanical gears were once manufactured, in which Citibank, Ernst & Young, and other multinational companies will soon be doing their alchemy.

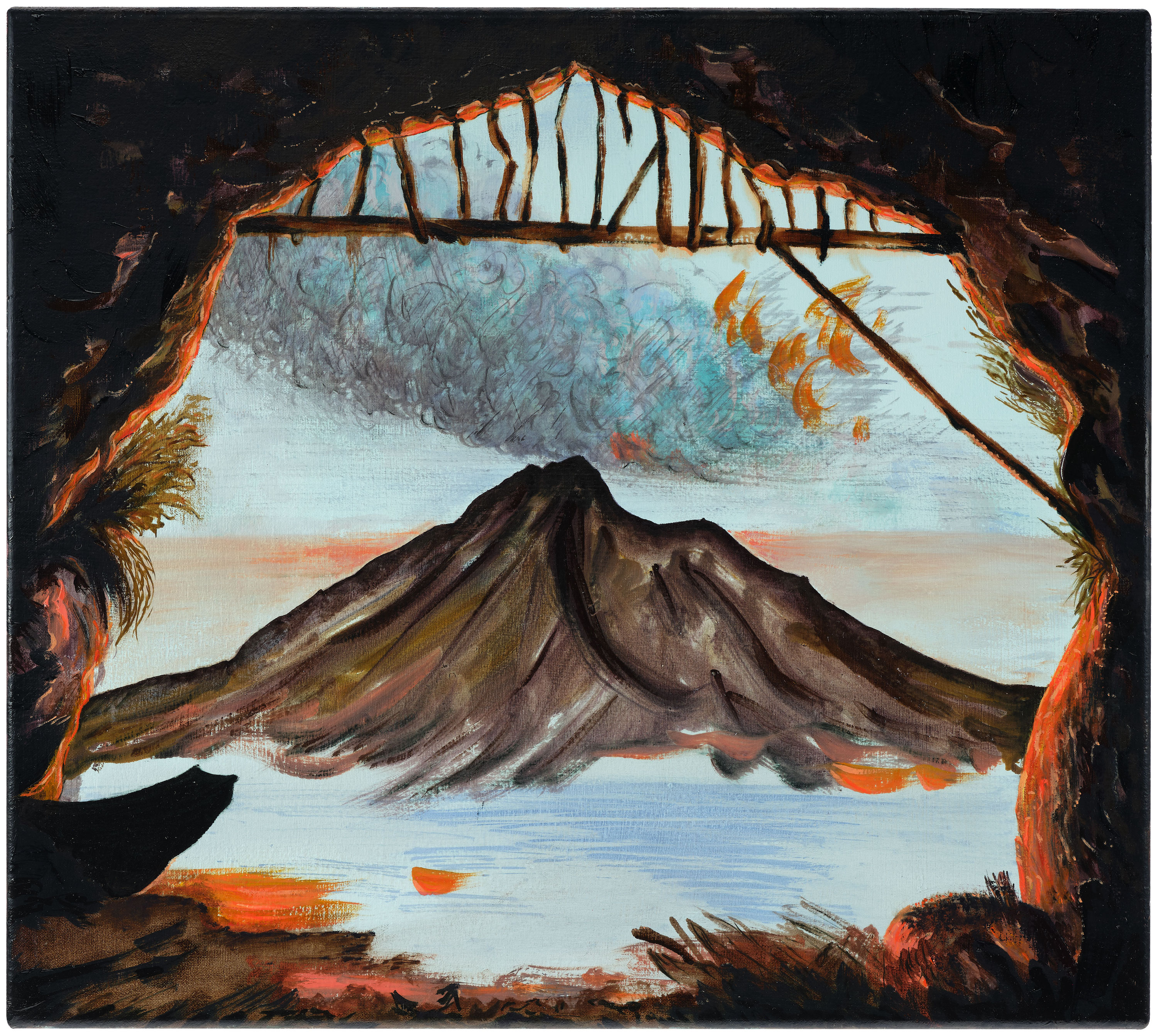

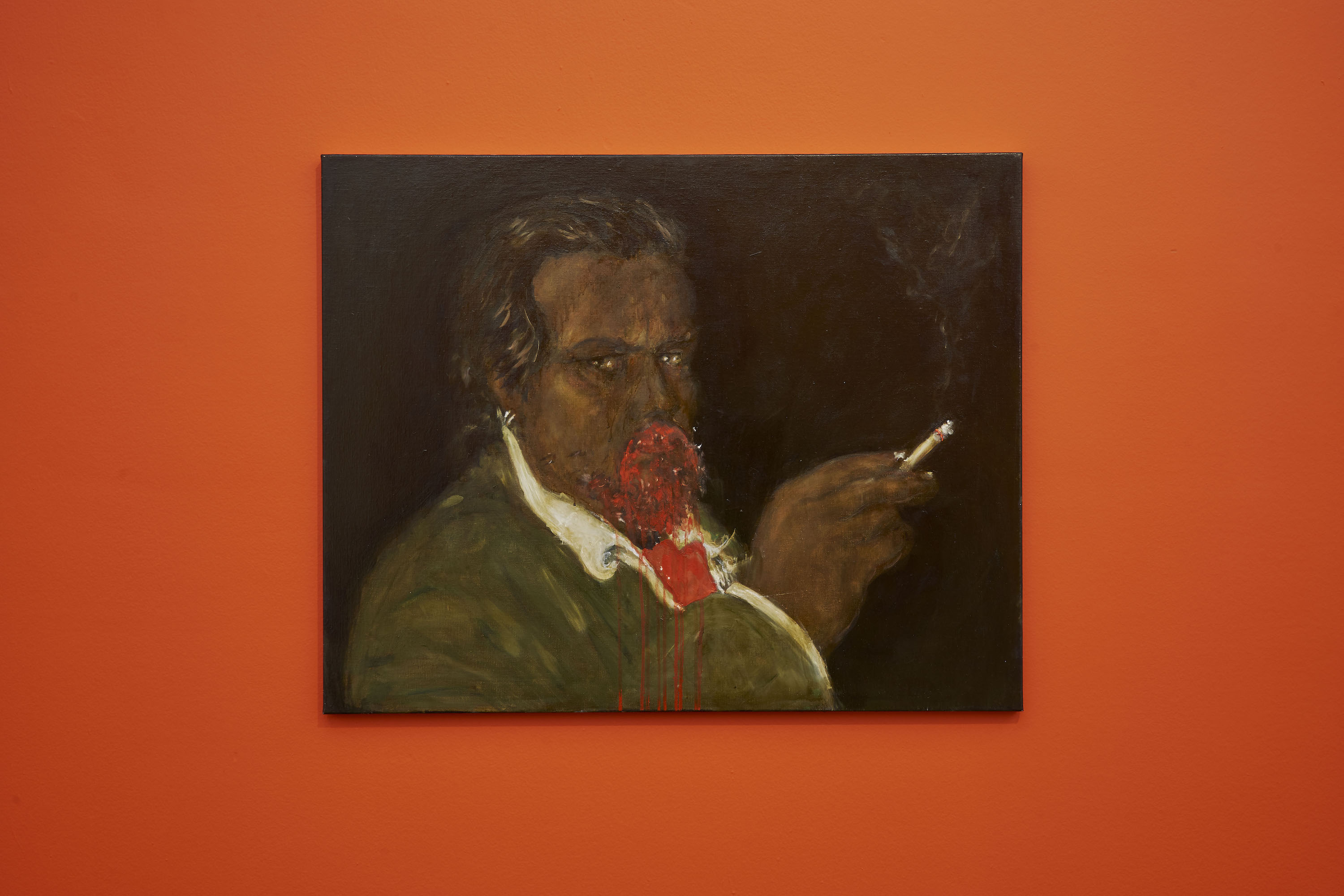

The Diagonal building opening unexpectedly echoed the Löwenbräu opening experience as people crowded on stairs and huddled in bottlenecks of the building, particularly keen to enjoy new views of the edifice towering over them. While Franz West sculptures paraded through Eva Presenhuber’s premises demonstrating their very generous proportions, Kilchmann was devoted to three painters, discretely hung. Unlike Kilchmann’s previous location which was more simply divided in two, his new space is a chain of galleries, in which one is greeted by Valérie Favre’s lapine ladies and ghosts upon entry. All of the deceptively sweet paintings shown are in the continuation of what Favre calls "painting nourished by dreams": their subjects tend to steal away from indistinct backgrounds in contrast to some of her earlier pneumatic bunnies and majorettes that jostled for attention with their artificial bodies. Two canvases from 2011 dominate: Die Henkerin III (The Executioner III), who seems unperturbed by the truncation of her own body below the waist, and the immersive landscape Wenn die Stadt Schläft II (While The City Sleeps II) after the film Asphalt Jungle (1950) by John Huston. Though the latter cites Huston and recreates a scene from Jacques Demy’s 1970 film Peau d’âne, its yellow-green hues and horses with lowered muzzles also evoke John Constable’s pastoral scenes.

Next door, this widescreen motif is picked up in a glorious ten-meter wide, five-panel work by John Armleder, Chrysanthemum parthenium (2008). The drip paintings presented here all date from 2008, though they nestle on a more recent work, Pierrotin (2010) with its rough, white oakum fuzz covering the walls. Each canvas carries a horticultural title, whose elaborate Latin hides brisker appellations such as the flowering onion (Allium aflatunense) akin to the motifs Armleder has frequently used as repeat pattern wall works; the white baneberry of Actaea pachypoda seems to beg a graphic reproduction of its goggle-eyed flowers. But though the glittering drips are a celebratory christening of this new gallery, the installation is the weak point of all three shows, not quite enabling the suspension of disbelief required to dive into the woolly environment.

As Peter Kilchmann and co. waited impatiently to move into their new premises these past few months, they could take comfort in Francis Alÿs’s patient experience tracking down tornadoes for the film that was shown at last year’s Tate and WIELS exhibitions. While Tornado (2000-10) cuts to the chase as Alÿs runs into the center of towers of swirling dust, Kilchmann shows the drawings he made passing the time till the phenomenon appeared. These little sandy landscapes are overlaid with titles relating to the larger metaphor of the tornado as a regime on the point of collapse. Alongside "turbulence" are "uncertainty," "control," "representation," and "chaos," among others, and the repetition of "in a given situation" or, in Portuguese, "numa dada situação." And of course there is the reference to Dada, brought back to its Zurich origins, which intimates that Alÿs was enjoying this solitary time, the absurdity of his enterprise, and the possibility of his own failure.