September 9–October 29, 2016

Rows of numbers instill in me a sickening panic. I got that feeling, familiar from childhood mathematics lessons and annual tax returns, in Hanne Darboven’s current exhibition at Sprüth Magers, Los Angeles.

Perhaps there was no need for such histrionics. In 1973, the West German Darboven told the writer Lucy Lippard that her art has “nothing to do with mathematics. Nothing!” For Darboven, numbers were a means of marking out time and space, “writing without describing.”1 For the most part, her work is not as concerned with calculation as with counting. Numbers, written sequentially, are akin to seconds ticking on a clock, days counted on a calendar or beats in a piece of music. (Indeed, in 1979 Darboven developed a system of musical notation which she used until the end of her life, in 2009, to write compositions for chamber orchestras and string quartets.)

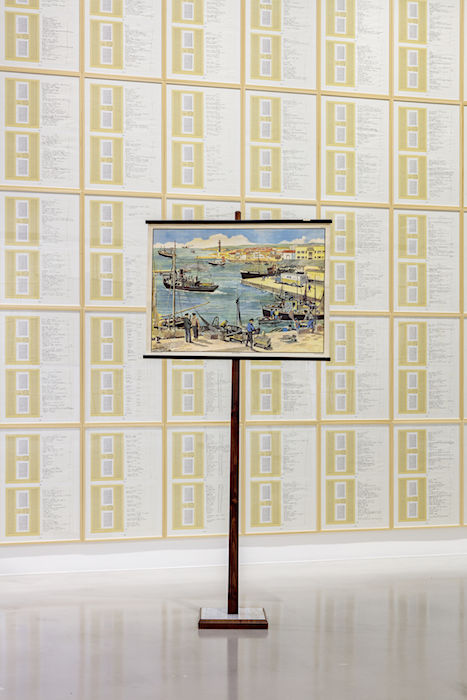

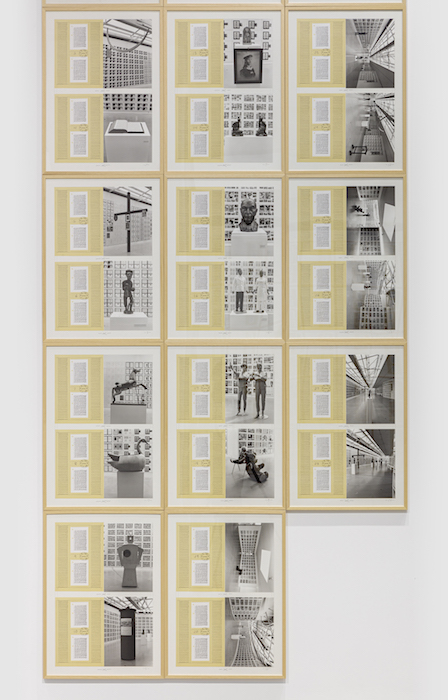

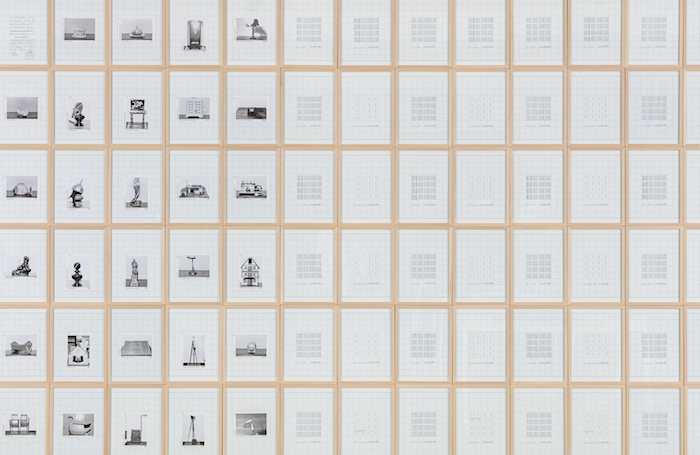

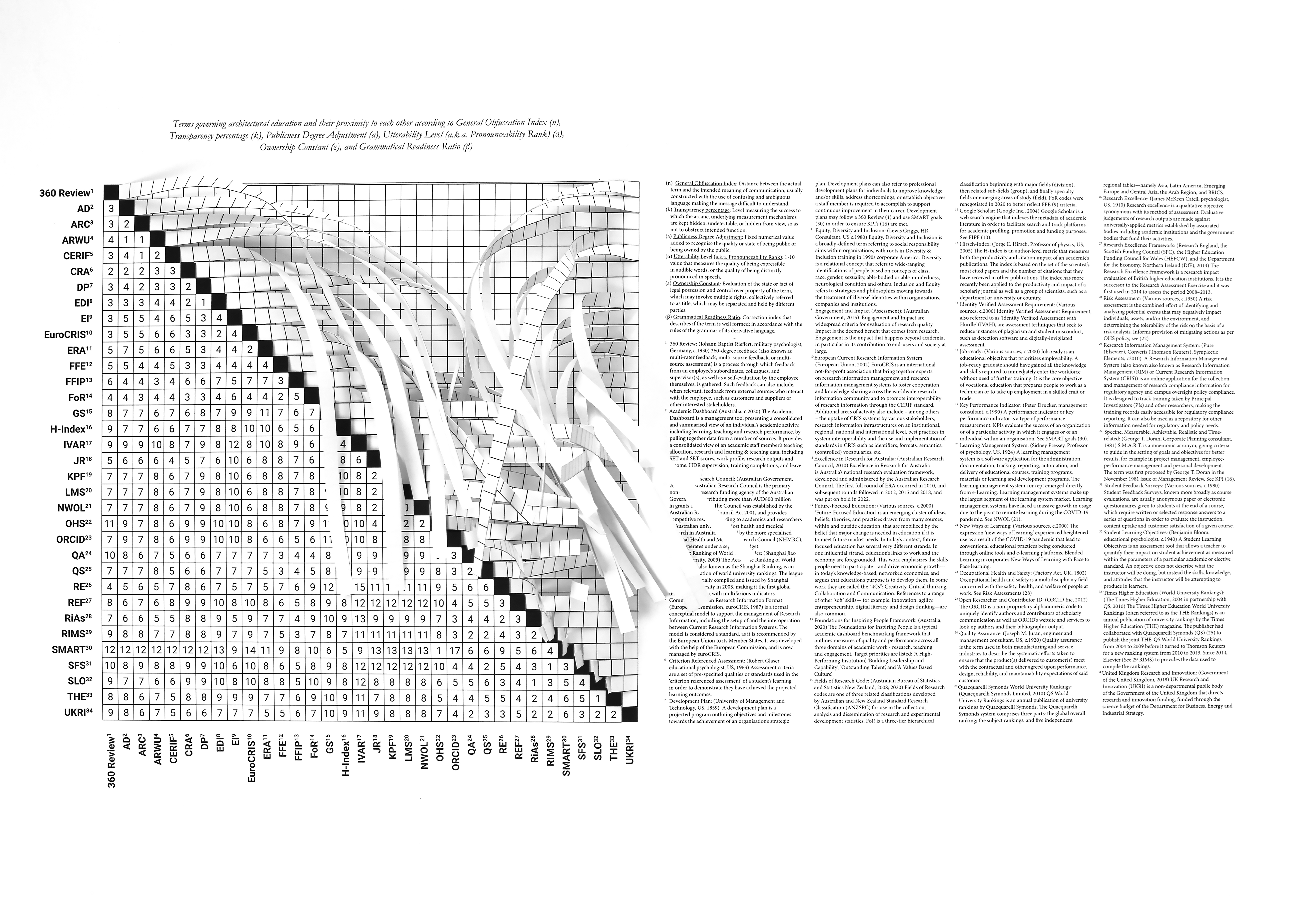

Darboven’s work generally consists of gridded pages of annotations and numerical inscriptions, sometimes handwritten, sometimes typed or printed; in 1978 she began including collaged elements such as her photographs and cuttings from books. In a single work, these pages can number in the hundreds or thousands. On the ground floor of the gallery, the staggering Erdkunde I, II, III (Geography I, II, III) (1986) is the earliest work in this show, and perhaps the most confounding. It includes 723 panels of text and collage; upstairs, another work, Leben, leben / Life, Living 1997-1998 (1998) comprises 2782 individually framed pages.

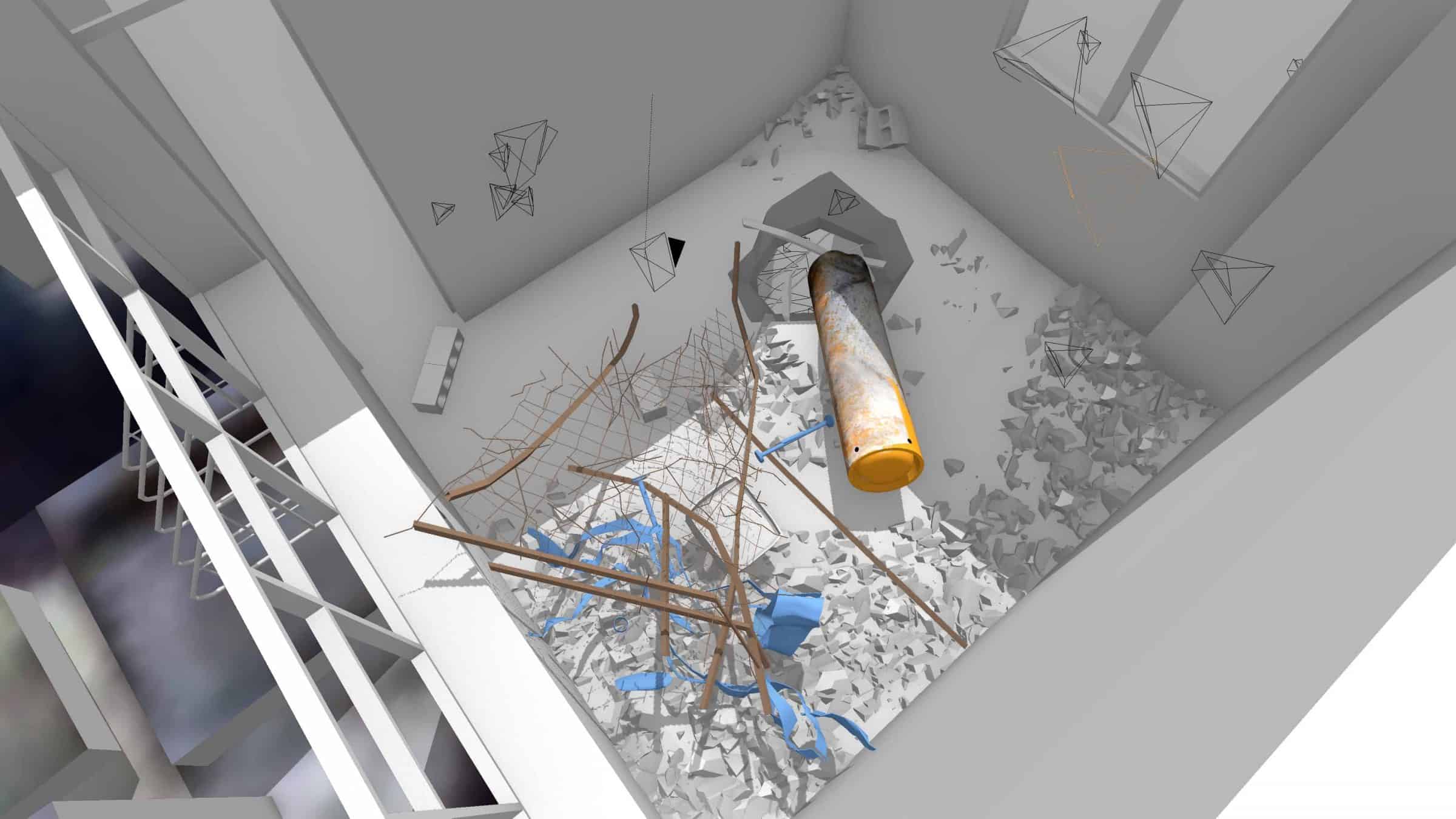

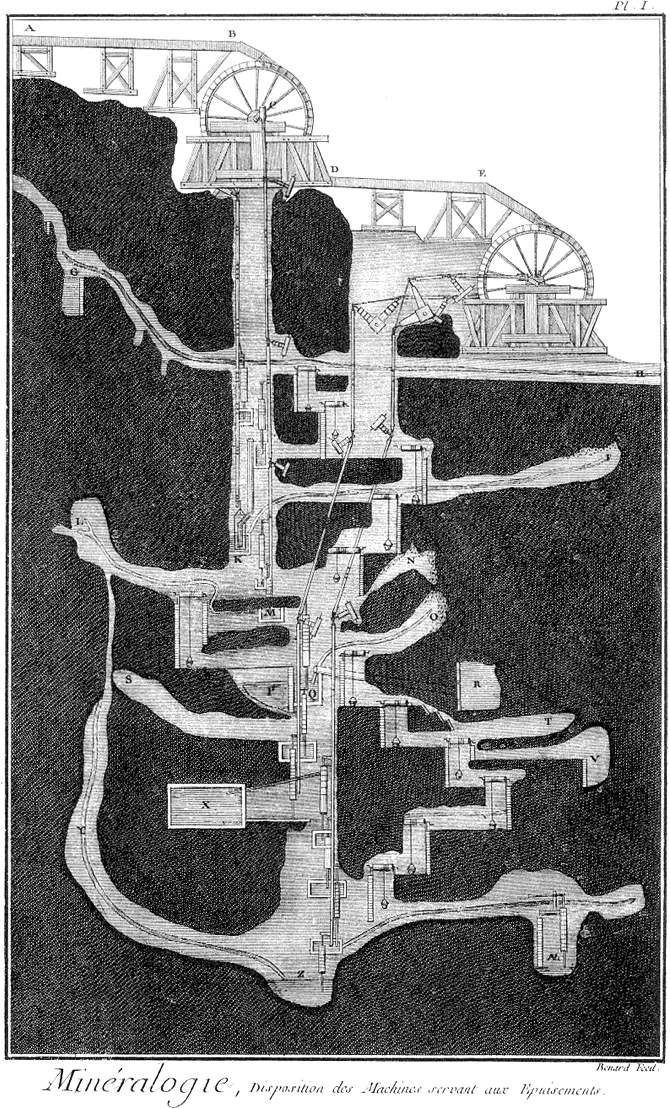

Erdkunde I, II, III departs from the form of the encyclopedia. Part one is an index, of sorts, although it also contains transcriptions and printed excerpts from the Brockhaus encyclopedia’s entries for Erde [earth] and Erdkunde [geography]. Parts two and three consist of Darboven’s own entries for these subjects: a numbered system of index cards, each bearing a single word or name. Most are places, but among “Alpen,” “München,” and “Park” are entries for “Bacall, L.,” “Hefner, H.,” and “Hitler, A.” No rationale, method, or context is provided. Unlike the Brockhaus, Darboven’s piece is unusable in any conventional sense. It is both brimming with information, and virtually empty. Printed pages that occur throughout are filled with looping lines, resembling abstracted script, saying nothing. Erdkunde I, II, III is a visualization not of knowledge itself but of the drives and methodologies involved in getting and keeping it.

One challenge here is in finding a way to read work that is based in apparently rational systems of numbers and words but which is, more often than not, illegible or unresolvable. This illegibility is not aided by my own poor German, nor by Darboven’s erratic handwriting. Leben, leben / Life, Living 1997-1998 involves an idiosyncratic method of numbering a daily calendar for the twentieth century. Try as I might, I cannot follow Darboven’s logic.

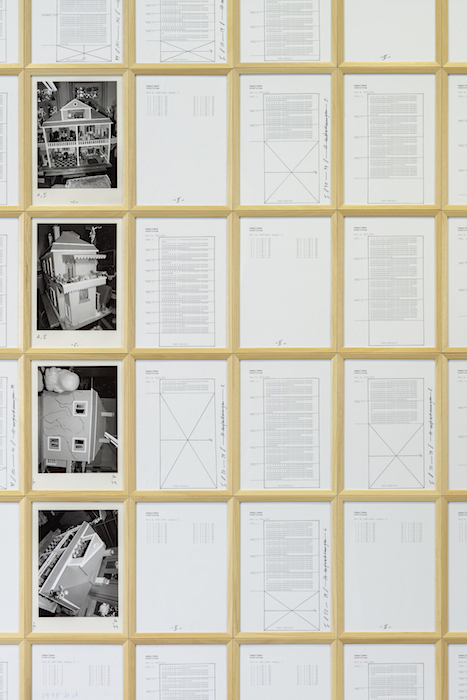

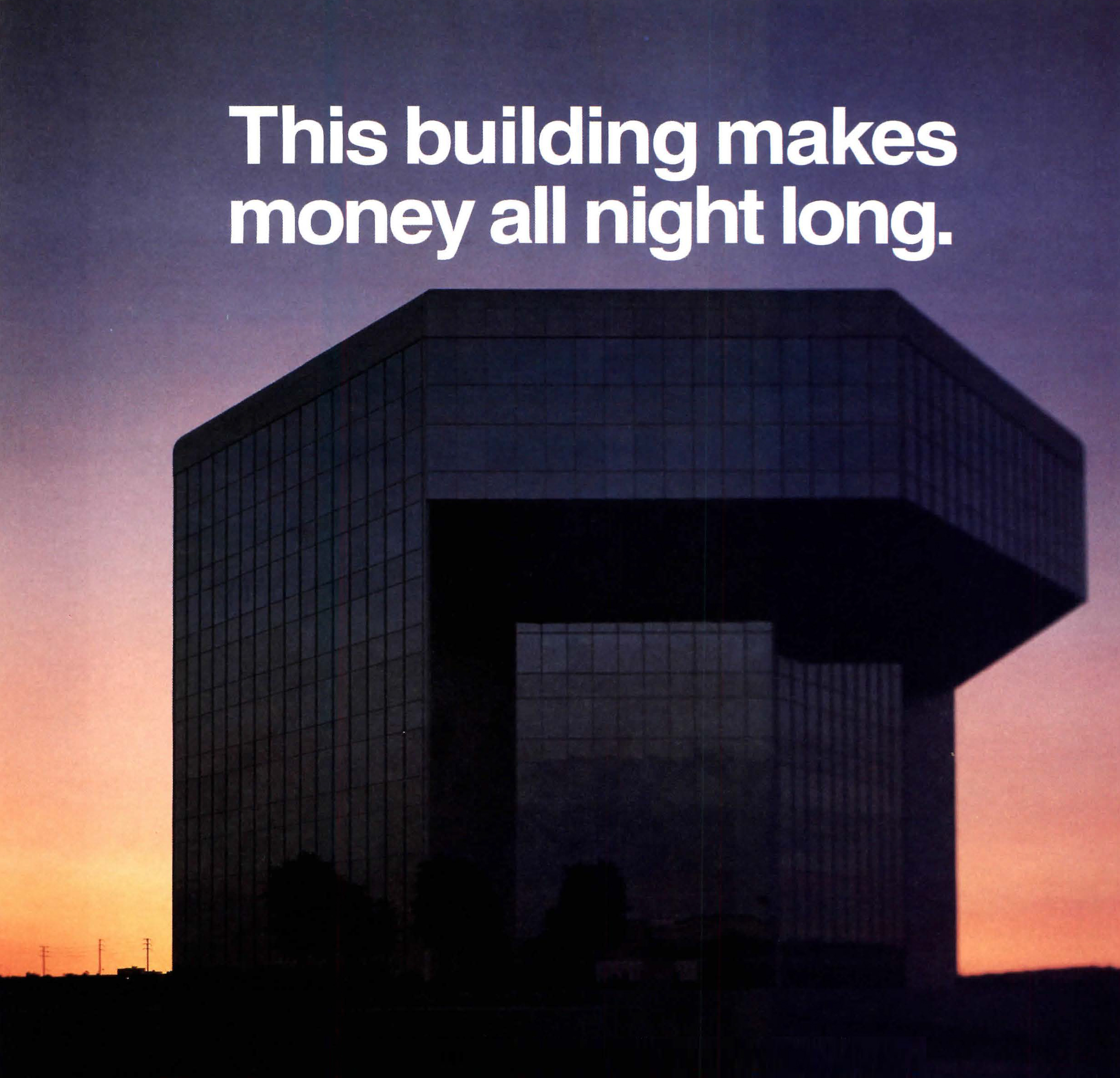

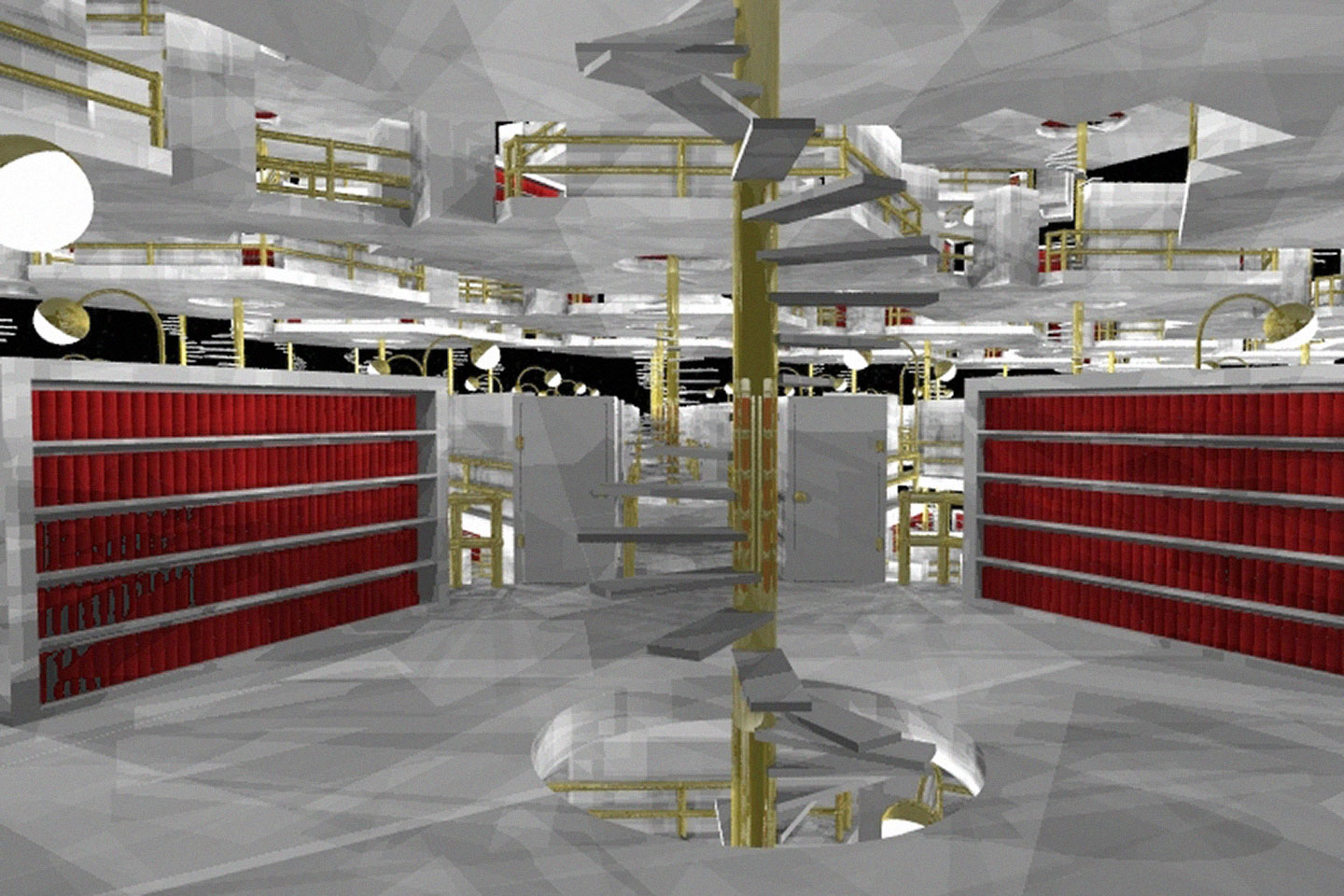

Often, it seems as if Darboven is deliberately complicating—even corrupting—her own systems. In Erdkunde I, II, III, she interrupts the flow with photographs of her studio and of her famous earlier work Cultural History 1880–1983 (1980–83) at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, exhibited in 1986, as if it were another form of index. We catch glimpses of wry humor, too. Around the gallery, antique children’s classroom posters condense convoluted systems—an industrial milking parlor, for example, or “2000 years of history”—into unintimidating illustrations. Darboven was evidently partial to these macro perspectives. In Leben, leben / Life, Living, two dolls’ houses—one traditional, one modernist—are included in the installation, along with photographs of the same dolls’ houses in the artist’s home. Darboven was an inveterate hoarder and her collections of bric-a-brac and antiques often made their way into her work. When viewed as analogous systems to her numerical works, these sprawling collections grant the latter a subjective looseness while they themselves absorb something of a process-oriented rigor.

The photographs featured in Darboven’s work are a means of tying the seemingly impersonal structures of Systems art to the disorderly flotsam and jetsam washed up by the tides of history. She is concerned with understanding time not only in an abstract philosophical sense but also as the structure underpinning all sociological and political phenomena. Time is never neutral or innocent in her work.

The most compelling piece in the exhibition also happens to be the most concise. (A relative term in Darboven’s case.) Für Abraham Lincoln [For Abraham Lincoln] (1996) hangs in a back room, set apart from the main exhibition due to space constraints. A photograph of two antique figurines recurs across 776 panels: a stooped black man, carved in polished wood, lifting up a figurine of Lincoln. The dynamic forced by Darboven onto the images of these two found objects is troubling and far from valedictory; her insertion of pages from a “classic jazz” calendar from 1989—in which every famous musician is black—is an ambivalent measure of the years since 1863, when the Emancipation Proclamation was passed. As with the other works in this exhibition, Darboven presents a selection of facts, without comment: writing without describing.

Hanne Darboven, quoted in Lucy Lippard, "Hanne Darboven: Deep in Numbers," Artforum 12, no. 2 (October 1973): 35–36.