Traditionally, the main occupation of art was to resist the flow of time. Public art museums and big private art collections were created to select certain objects—the artworks—take them out of private and public use, and therefore immunize them against the destructive force of time. Thus, our art museums became huge garbage cans of history in which things were kept and exhibited that had no use anymore in real life: sacral images of past religions or status objects of past lifestyles. During a long period of art history, artists also participated in this struggle against the destructive force of time. They wanted to create artworks that would be able to transcend time by embodying eternal ideals of beauty or, at least, by becoming the medium of historical memory, by acting as witnesses to events, tragedies, hopes, and projects that otherwise would have been forgotten. In this sense, artists and art institutions shared a fundamental project to resist material destruction and historical oblivion.

Art museums, in their traditional format, were based on the concept of a universal art history. Accordingly, their curators selected artworks that seemed to be of universal relevance and value. These selective practices, and especially their universalist claims, have been criticized in recent decades in the name of the specific cultural identities that they ignored and even suppressed. We no longer believe in universalist, idealist, transhistorical perspectives and identities. The old, materialist way of thinking let us accept only roles rooted in the material conditions of our existence: national-cultural and regional identities, or identities based on race, class, and gender. And there are a potentially infinite number of such specific identities because the material conditions of human existence are very diverse and are permanently changing. However, in this case, the initial mission of the art museum to resist time and become a medium of mankind’s memory reaches an impasse: if there is a potentially infinite number of identities and memories, the museum dissolves because it is incapable of including all of them.

While the museum emerged as a kind of secular surrogate for divine memory during the Enlightenment and the French Revolution, it is merely a finite material object—unlike infinite divine memory that can, as we know, include all the identities of all people who lived in the past, live now, and will live in the future.

But is this vision of an infinite number of specific identities even correct, e.g., truly materialist? I would suggest that it is not. Materialist discourse, as initially developed by Marx and Nietzsche, describes the world in permanent movement, in flow—be it dynamics of the productive forces or Dionysian impulse. According to this materialist tradition, all things are finite—but all of them are involved in the infinite material flow. So there is a materialist universality—the universality of the flow.

However, is it possible for a human being to enter the flow, to get access to its totality? On a certain very banal level the answer is, of course, yes: human bodies are things among other things in the world and, thus, subjected to the same universal flow. They become ill, they age, and they die. However, even if human bodies are subjected to aging, death, and dissolution in the flow of material processes, it does not mean that their inscriptions into cultural archives are also in flow. One can be born, live, and die under the same name, having the same citizenship, same CV, and same website—that means remaining the same person. Our bodies, then, are not the only material supports of our persons. From the moment of our birth we are inscribed into certain social orders—without our consent or often even knowledge of this fact. The material supports of our personality are state archives, medical records, passwords to certain internet sites, and so forth. Of course, these archives will also be destroyed by the material flow at some point in time. But this destruction takes an amount of time that is non-commensurable with our own lifetimes. Thus, there is a tension between our material, physical, corporeal mode of existence—which is temporary and subjected to time—and our inscription into cultural archives that are, even if they are also material, much more stable than our own bodies.

Traditional art museums are a part of these cultural archives—even if they claim to represent the subjectivity, personality, and individuality of artists in a more immediate and richer way than other cultural archives are capable of doing. Art museums, like all other cultural archives, operate by restoration and conservation. Again: artworks as specific material objects—as art bodies, so to speak—are perishable. But this cannot be said about them as publicly accessible, visible forms. If its material support decays and dissolves, the form of a particular artwork can be restored or copied and placed on a different material base. The history of art demonstrates both these substitutions of old supports by new supports and the efforts of restoration and reconstruction. Thus, the individual form of an artwork insofar as it is inscribed in the archives of art history remains intact—only marginally affected by material flux, if at all. And we believe that it is precisely this form that, after the artist’s death, somehow manifests his or her soul—or at least a certain zeitgeist or certain cultural identity that has disappeared.

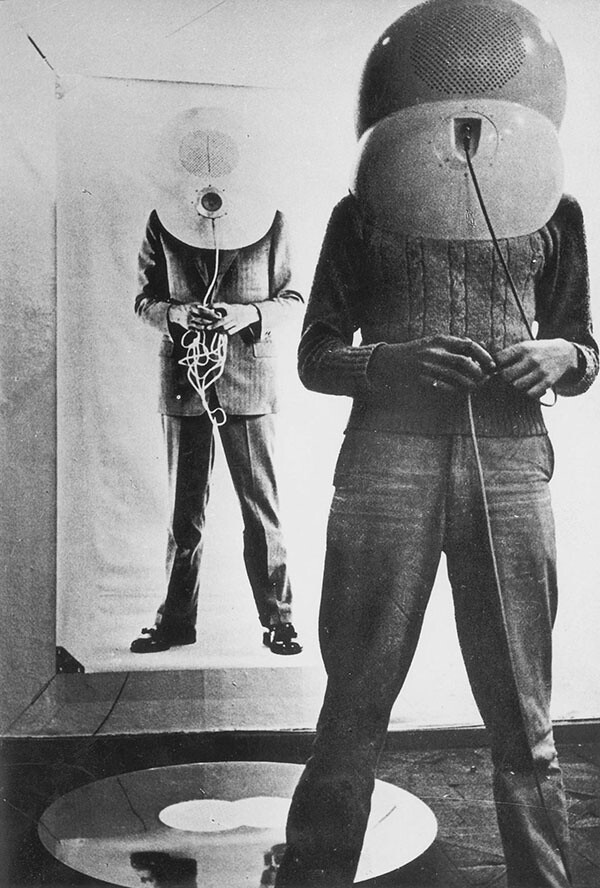

We can thus say that the traditional art system is based on desynchronizing the time of the individual, material human existence from the time of its cultural representation. However, the artists of the historical avant-garde and later some artists of the 1960s and 1970s already tried to resynchronize the fate of the human body with the mode of its historical representation—to embrace the precariousness, instability, and finiteness of our material existence. Not to resist the flow of time, but to let it define one’s own artwork, to pursue a certain self-propelled fluidity, rather than trying to make the work, or oneself, into a self-eternalizing being. The idea was to make the form itself fluid. However, the following question emerges: What is the effect of this radicalized precariousness, of this will to resynchronize the living body with its cultural representation within the relationship of artists to art institutions?

I would suggest that the relationship between these entities went through two different periods: the first is enmity on the part of the artist against the art system and, especially, art museums, complete with attempts to destroy them in the name of living art. The second encompasses the slow morphing of museums themselves into a stage, on which the flow of time is performed. If we ask ourselves what institutional form the classical avant-garde proposed as a substitute for the traditional museum, the answer is clear: it is the Gesamtkunstwerk. In other words, the total art event involving everybody and everything—as a replacement for a totalizing space of trans-temporal artistic representation of everybody and everything.

Wagner introduced the notion of the Gesamtkunstwerk in his programmatic treatise “The Art-Work of the Future” (1849–1850). Wagner wrote this text in exile, in Zurich, after the end of the revolutionary uprisings in Germany in 1848. In this text he develops a project for an artwork (of the future) that is heavily influenced by the materialist philosophy of Ludwig Feuerbach. At the beginning of his treatise, Wagner states that the typical artist of his time is an egoist who, in complete isolation from the life of the people, practices his art exclusively for the enjoyment of the rich; in so doing he follows the dictates of fashion. The artist of the future, says Wagner, must become radically different: “He now can only will the universal, true, and unconditional; he yields himself not to a love for this or that particular object, but to wide Love itself. Thus does the egoist become a communist.”1

Becoming communist, then, is possible only through self-renunciation—self-dissolution in the collective. Wagner defines his supposed hero as such: “The last, most complete renunciation [Entäusserung] of his personal egoism, the demonstration of his full ascent into universalism, a man can only show us by his Death; and that not by his accidental, but by his necessary death, the logical sequel to his actions, the last fulfillment of his being. The celebration of such a death is the noblest thing that men can enter on.”2 Admittedly, there remains a difference between the hero who sacrifices himself and the performer who makes this sacrifice onstage (the Gesamtkunstwerk being understood by Wagner as a musical drama). Nonetheless, Wagner insists that this difference is suspended by the Gesamtkunstwerk, for the performer “does not merely represent in the art-work the action of the fêted hero, but repeats its moral lesson; insomuch as he proves by this surrender of his personality that he also, in his artistic action, is obeying a dictate of necessity which consumes the whole individuality of his being.”3 In other words, Wagner understands the Gesamtkunstwerk precisely as a way of resynchronizing the finiteness of human existence with its cultural representation—which, in turn, also becomes finite.

All the other performers achieve their own artistic significance solely through participating in the hero’s ritual of self-sacrifice. Accordingly, Wagner speaks of the hero performer as a dictator who mobilizes the collective of collaborators, with the exclusive goal of staging his own sacrifice in the name of this collective. In the sacrificial scene, the Gesamtkunstwerk finds its end—there is no continuation, no memory. In other words, there is no further role for the dictator-performer. The artistic collective dissolves, and the next Gesamtkunstwerk is created by another artistic collective, with a different dictator-performer in the main role. Here the precariousness of an individual human existence and the fluidity of working collectives are artistically embraced, and even radicalized. Historically, we know that many artistic collectives followed this model: from Hugo Ball’s Cabaret Voltaire to Andy Warhol’s Factory and Guy Debord’s Situationist International. But the contemporary name for this temporary and suicidal dictatorship is different: the “curatorial project.”

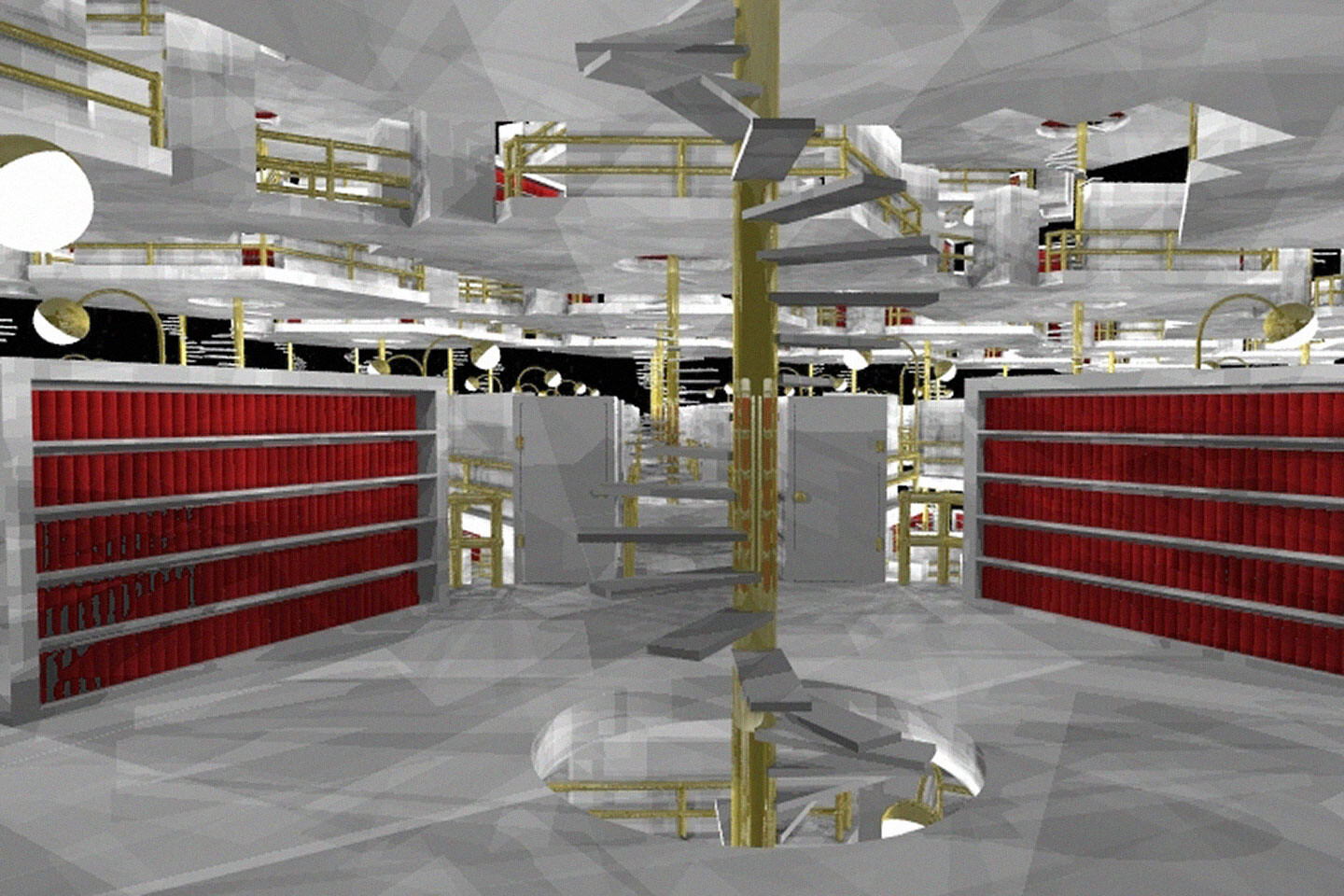

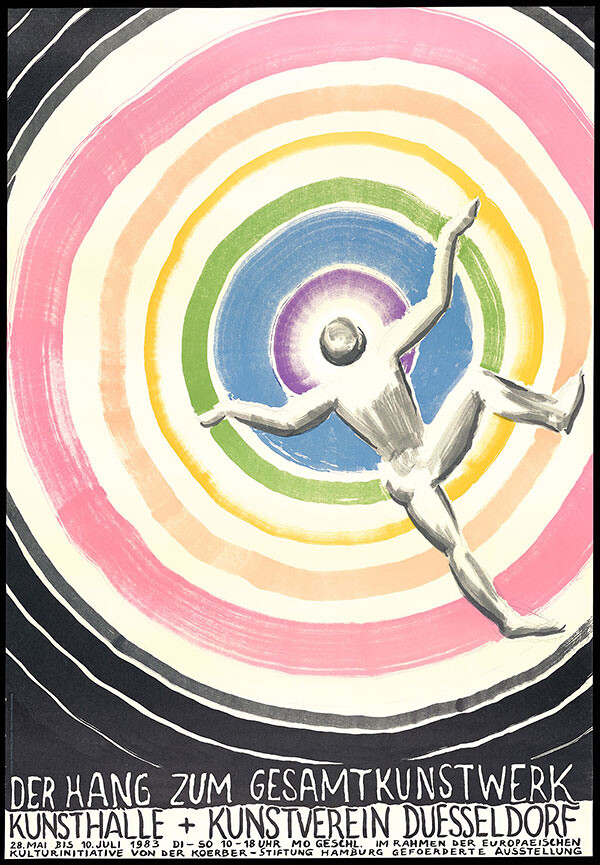

Harald Szeemann, who initiated the curatorial turn in contemporary art, was so fascinated by the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk that he organized an exhibition called “The Tendency to Gesamtkunstwerk” [“Hang zum Gesamtkunstwerk”] (1984). Considering this historical show based on the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk, it becomes necessary to ask: What is the main difference between a traditional exhibition and a modern curatorial project? The traditional exhibition treats its space as anonymous and neutral. Only the exhibited artworks are important—but not the space in which they are exhibited. Thus, artworks are perceived and treated as potentially eternal—and the space of the exhibition as a contingent, accidental station where the immortal artworks take a temporary rest from their wanderings through the material world. In contrast, the installation—be it artistic or curatorial—inscribes the exhibited artworks in this contingent material space. (Here one can see an analogy between this shift and the shift from theater actor or cinema actor to the director of theater and cinema.)

The curatorial project, rather than the exhibition, is then the Gesamtkunstwerk because it instrumentalizes all the exhibited artworks and makes them serve a common purpose that is formulated by the curator. At the same time, a curatorial or artistic installation is able to include all kinds of objects: time-based artworks or processes, everyday objects, documents, texts, and so forth. All these elements, as well as the architecture of the space, sound, or light, lose their respective autonomy and begin to serve the creation of a whole in which visitors and spectators are also included. Thus, stationary artworks of the traditional sort become temporalized, subjected to a certain scenario that changes the way they are perceived during the time of the installation because this perception is dependent on the context of their presentation—and this context begins to flow. Thus, ultimately, every curatorial project demonstrates its accidental, contingent, eventful, finite character—in other words, it enacts its own precariousness.

Indeed, every curatorial project necessarily aims to contradict the normative, traditional art-historical narrative embodied by the museum’s permanent collection. If such a contradiction does not take place, the curatorial project loses its legitimation. For the same reason, the next curatorial project should contradict the previous one. A new curator is a new dictator who erases the traces of the previous dictatorship. In this way, contemporary museums continually morph from spaces for permanent collections into stages for temporary curatorial projects—temporary Gesamtkunstwerks. And the main goal of these temporary curatorial dictatorships is to bring art collections into the flow—to make art fluid, to synchronize it with the flow of time.

As previously mentioned, at the beginning of this process of synchronization, artists wanted to destroy art museums. Malevich offers a good example of this in his short but important text “On the Museum,” from 1919. At that time, the new Soviet government feared that the old Russian museums and art collections would be destroyed by civil war and the general collapse of state institutions and the economy. The Communist Party responded by trying to secure and save these collections. In his text, Malevich protested against this pro-museum policy by calling on the Soviet state to not intervene on behalf of the old art collections, because, he said, their destruction could open the path to true, living art. In particular, he wrote:

Life knows what it is doing, and if it is striving to destroy, one must not interfere, since by hindering we are blocking the path to a new conception of life that is born within us. In burning a corpse we obtain one gram of powder: accordingly thousands of graveyards could be accommodated on a single chemist’s shelf. We can make a concession to conservatives by offering that they burn all past epochs, since they are dead, and set up one pharmacy.

Later, Malevich gives a concrete example of what he means:

The aim [of this pharmacy] will be the same, even if people will examine the powder from Rubens and all his art—a mass of ideas will arise in people, and will be often more alive than actual representation (and take up less room).4

It is obvious that what Malevich proposes here is not merely the destruction of museums but a radical curatorial project—to exhibit the ashes of artworks instead of their corpses. And in a truly Wagnerian manner, Malevich further says that everything that “we” (meaning he and his artistic contemporaries) do is also destined for the crematorium. Of course, contemporary curators do not reduce museum collections to ashes, as Malevich suggested. But there is a good reason for that. Since Malevich’s time, mankind has invented a way to place all artworks from the past on one chemist’s shelf without destroying them. And this shelf is called the internet.

Indeed, the internet has transformed the museum in the same way that photography and cinema transformed painting and sculpture. Photography made the mimetic function of the traditional arts obsolete, and thus pushed these arts in a different—actually opposite—direction. Instead of reproducing and representing images of nature, art came to dissolve, deconstruct, and transform these images. The attention thus shifted from the image itself to the analysis of image production and presentation. Similarly, the internet made the museum’s function of representing art history obsolete. Of course, in the case of the internet, spectators lose direct access to the original artworks—and thus the aura of authenticity gets lost. And so museum visitors are invited to undertake a pilgrimage to art museums in search of the Holy Grail of originality and authenticity.

At this point, however, one has to be reminded that according to Walter Benjamin, who originally introduced the notion of aura, artworks lost their aura precisely through their museumification. The museum already removes art objects from their original sites of inscription in the historical here and now. Thus for Benjamin, artworks that are exhibited in museums are already copies of themselves—devoid of their original aura of authenticity. In this sense, the internet, and its art-specialized websites, merely continue the process of the de-auratization of art started by art museums. Many cultural critics have therefore expected—and still expect—that public art museums will ultimately disappear, unable to compete economically with private collectors operating on the increasingly expensive art market, and be replaced by much cheaper, more accessible virtual, digitized archives.

However, the relationship between internet and museum radically changes if we begin to understand the museum not as a storage place for artworks, but rather as a stage for the flow of art events. Indeed, today the museum has ceased to be a space for contemplating non-moving things. Instead, the museum has become a place where things happen. Events staged by museums today include not only curatorial projects, but also lectures, conferences, readings, screenings, concerts, guided tours, and so forth. The flow of events inside the museum is today often faster than outside its walls. Meanwhile, we have grown accustomed to asking ourselves, what is going on in this or that museum? And to find the relevant information, we search for it on the museums’ websites, but also on blogs, social media pages, Twitter, and so forth. We visit museums far less often than we visit their websites and follow their activities across the internet. And on the internet, the museum functions as a blog. So the contemporary museum does not present universal art history, but rather its own history—as a chain of events staged by the museum itself. But most importantly: the internet relates to the museum in the mode of documentation, not in the mode of reproduction. Of course, the museums’ permanent collections can be reproduced on the internet, but the museum’s activities can only be recorded.

Indeed, one cannot reproduce a curatorial project; one can only document it. The reason for this is twofold. First, the curatorial project is an event, and one cannot reproduce an event because it cannot be isolated from the flow of time. An artwork can be reproduced because it has an atemporal status from the beginning, but the process of the production and exposure of this artwork can only be documented. Second, curatorial and artistic installation is a Gesamtkunstwerk that can be experienced only from within. The traditional artwork is perceived from an outside position, but an artistic event is experienced from a position inside the space in which this event takes place. In this way, visitors to a curatorial or artistic installation enter the space of the installation and then begin to position themselves inside this space, to experience it from within rather than from without. However, the movement of a camera can never fully coincide with the movement of an individual visitor’s gaze—as the position of a painter or a photographer making a reproduction of a painting coincides with the gaze of an average spectator. And if any form of documentation attempts to reconstruct the inner view and experience of an art event from different positions, it necessarily becomes fragmentary. That is why we can re-cognize the traditional reproduction of an artwork but are never able to fully re-cognize the documentation of an art event.

Nowadays, one speaks time and again about the theatralization of the museum. Indeed, in our time people come to exhibition openings in the same way as they went to opera and theater premieres in the past. This theatralization of the museum is often criticized because it might be seen as a sign of the museum’s involvement in the contemporary entertainment industry. However, there is a crucial difference between the installation space and the theatrical space. In the theater, spectators remain in an outside position vis-à-vis the stage, but in the museum they enter the stage, and find themselves inside the spectacle.

Thus, the contemporary museum realizes the modernist dream that the theater itself was never able to fully realize—of a theater in which there is no clear boundary between the stage and the space of the audience. Even if Wagner speaks about the Gesamtkunstwerk as an event that erases the border between stage and audience, the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth that was built under the direction of Wagner did not erase this border but, rather, radicalized it. Contemporary theater, including Bayreuth, uses more and more art, especially contemporary art, on stage—but it still does not erase the difference between stage and audience. The inclusion of contemporary installation art remains inscribed in the traditional scenography. However, in the context of an artistic and curatorial installation, the public is integrated into the installation space to become part of it.

The same can be said about mass entertainment. A pop concert or a film screening creates communities among those in attendance. However, mass culture itself cannot make these communities self-reflective—cannot thematize the event of building these transitory, precarious, contingent communities. The perspective of the audience during a pop concert or movie screening is too forward-directed—to the stage or screen—for them to adequately perceive and reflect upon the space in which they find themselves, or the communities to which they temporarily belong. That is the kind of reflection that advanced art installation allows us to achieve. To borrow Marshall McLuhan’s vocabulary, the medium of installation is a cool medium—unlike the internet, which is obviously a hot medium, because it requires users to be spatially separated and to concentrate their attention on a screen. By cooling down all other media, contemporary art installation offers visitors the possibility of self-reflection—and of reflection upon the immediate event of their coexistence with other visitors and exhibited objects—that other media are unable to offer to the same degree. Here, individual human beings are confronted with their common fate—with the radically contingent, transitory, precarious conditions of their existence.

Actually, the traditional museum as a place of things, and not events, can be equally accused of functioning as part of the art market. This kind of criticism is easy to formulate—and it is universal enough to be applied to any possible artistic strategy. But as we know, the traditional museum did not only display certain things and images; it also allowed theoretical reflection and analysis of them by means of historical comparison. Modern art has not merely produced things and images; it has also analyzed the thingness of things and the structure of the image. In addition, the art museum does not only stage events—it is also a medium for investigating the event, its boundaries, and its structure. If classical modern art investigated and analyzed the thingness of things, contemporary art begins to do the same in relation to events—to critically analyze the eventfulness of events. This investigation takes different forms, but it seems to me that its focal point is reflection on the relationship between event and its documentation—analogous to the reflection on the relationship between an original and its reproduction that was central to the art of modernism and postmodernism. Today, the amount of art documentation is permanently growing. One also begins to document performances, actions, exhibitions, lectures, concerts, and artistic projects that become more and more important in the framework of contemporary art.

One begins also to document the work of artists who produce artworks in a more traditional manner because they increasingly use the internet, or at least a personal computer, during their working process. And this offers the possibility of following the whole process of art production from its beginning to its end, since the use of digital techniques is observable. Here the traditional boundary between art production and art display begins to be erased. Traditionally, the artist produced an artwork in his or her studio, hidden from public view, and then exhibited a result, a product—an artwork that accumulated and recuperated the time of absence. This time of temporary absence is constitutive for what we call the creative process—in fact, it is precisely what we call the creative process.

André Breton tells a story about a French poet who, when he went to sleep, put on his door a sign that read: “Please, be quiet—the poet is working.” This anecdote summarizes the traditional understanding of creative work: creative work is creative because it takes place beyond public control—and even beyond the conscious control of the author. This time of absence could last days, months, years—even a whole lifetime. Only at the end of this period of absence was the author expected to present a work (maybe found in his papers posthumously) that would then be accepted as creative precisely because it seemed to emerge out of nothingness.

However, the internet and the computer in general are collective, observable, surveillable working places. We tend to speak about the internet in terms of an infinite data flow that transcends the limits of our control. But, in fact, the internet is a machine to stop and reverse data flow. The unobservability of the internet is a myth. The medium of the internet is electricity. And the supply of electricity is finite. So the internet cannot support an infinite data flow. The internet is based on a finite number of cables, terminals, computers, mobile phones, and other equipment. Its efficiency is based precisely on its finiteness and, therefore, on its observability. Search engines such as Google demonstrate this. Today, one hears a lot about the growing degree of surveillance, especially online. But surveillance is not something external to the internet, or merely a specific technical use of its services. The internet is, in its essence, a machine of surveillance. It divides the flow of data into small, traceable, and reversible operations, thus exposing every user to surveillance—real or potential. The internet creates a field of total visibility, accessibility, and transparency.

If the public follows my activity all the time, then I do not need to present it with any product. The process is already the product. Balzac’s unknown artist who could never finish his masterpiece would have no problem under these new conditions—documentation of his efforts would comprise this masterpiece and he would become famous. Documentation of the act of working on an artwork is already an artwork. With the internet, time became space indeed—and it is the visible space of permanent surveillance. If art has become a flow, it flows in a mode of self-documentation. Here action is simultaneous with its documentation, its inscription. And the inscription simultaneously becomes information that is spread through the internet and instantly accessible by everybody. This means that contemporary art work can produce no product—yet it still remains productive. But again: if the internet takes over the role of the museum as the place of memory—because the internet records and documents the activities of the artist even before his or her work is brought into the museum—what is the goal of the museum today?

Contemporary museum exhibitions are full of documentations of past artistic events, shown alongside traditional works of art. Thus, the museum turns the documentation of an old event into an element of a new event. It ascribes this documentation a new here and now—and as such gives it a new aura. But, unlike reproduction, documentation cannot be easily integrated into contemporaneity. The documentation of an event always produces nostalgia for a missed presence, a missed opportunity. It does not erase the difference between past and present, as reproduction tends to; instead, it makes the gap between past and present obvious—and in this way thematizes the flow of time. Heidegger described the whole world process as an event staged by Being. And he believed that we can get access to the eventfulness of this event only if Being itself offers us this possibility—through a clearance of being (Lichtung des Seins). Today’s museum is a place where the clearance of being is artificially staged.

In a world in which the goal of stopping the flow of time is taken over by the internet, the function of the museum becomes one of staging the flow—staging events that are synchronized with the lifetimes of the spectators. This changes the topology of our relationship to art. The traditional hermeneutical position towards art required the gaze of the external spectator to penetrate the artwork, to discover artistic intentions, or social forces, or vital energies that gave the artwork its form—from the outside of the artwork toward its inside. However, the gaze of the contemporary museum visitor is, by contrast, directed from the inside of the art event towards its outside: toward the possible external surveillance of this event and its documentation process, toward the eventual positioning of this documentation in the media space and in cultural archives—in other words, toward the spatial boundaries of this event. And also towards the temporal boundaries of this event—because when we are placed inside an event, we cannot know when this event began and when it will end.

The art system is generally characterized by the asymmetrical relationship between the gaze of the art producer and the gaze of the art spectator. These two gazes almost never meet. In the past, after artists put their artworks on display, they lost control over the gaze of the spectator: regardless of what some art theoreticians say, the artwork is a mere thing and cannot meet the spectator’s gaze. So under the conditions of the traditional museum, the spectator’s gaze was in a position of sovereign control—although this sovereignty could be indirectly manipulated by the museum’s curators through certain strategies of pre-selection, placement, juxtaposition, lighting, and so forth. However, when the museum begins to function as a chain of events, the configuration of gazes changes. The visitor loses his or her sovereignty in a very obvious way. The visitor is placed inside an event and cannot meet the gaze of a camera that documents this event—nor the secondary gaze of the editor that does the postproduction work on this document, nor the gaze of a later spectator of this document.

That is why, by visiting contemporary museum exhibitions, we are confronted with the irreversibility of time—we know that these exhibitions are merely temporary. If we visit the same museum after a certain amount of time, the only things that will remain will be documents: a catalogue, or a film, or a website. But what these things offer us is necessarily incommensurable with our own experience because our perspective, our gaze is asymmetrical with the gaze of a camera—and these gazes cannot coincide, as they could in the case of documenting an opera or a ballet. This is the reason for a certain kind of nostalgia that we necessarily feel when we are confronted with documents of past artistic events, whether exhibitions or performances. This nostalgia provokes the desire to reenact the event “as it truly was.”

Recently in Venice, the exhibition “When Attitudes Become Form” was reenacted at the Fondazione Prada. It was a very professional reenactment—and so it provoked a new and even stronger wave of nostalgia. Some people thought how great it would be to go back to the 1960s and breathe the wonderful atmosphere of that time. And they also thought how awful everything is at the Biennale itself, with all its fuss, compared to the sublime askesis of “When Attitudes Become Form.” At the same time, visitors from a younger generation found the exhibition unimpressive, and liked only the beautiful guides in their Prada clothes.

The nostalgic mood that is inevitably provoked by art documentation reminds me of the early Romantic nostalgia towards nature. Art was seen then as the documentation of the beautiful or sublime aesthetic experiences that were offered by nature. The documentation of these experiences by means of painting seemed more disappointing than authentic. In other words, if the irreversibility of time and the feeling of being inside rather than outside an event were once the privileged experiences of nature, they now became the privileged experiences of contemporary art. And that means precisely that contemporary art has become the medium for investigating the eventfulness of events: the different modes of the immediate experience of events, their relationship to documentation and archiving, the intellectual and emotional modes of our relationship to documentation, and so forth. Now, if the thematization of the eventfulness of the event has become, indeed, the main preoccupation of contemporary art in general and the museum of contemporary art in particular, it makes no sense to condemn the museum for staging art events. On the contrary, today the museum has become the main analytical tool for staging and analyzing the event as radically contingent and irreversible—amidst our digitally controlled civilization that is based on tracking back and securing the traces of our individual existence in the hope of making everything controllable and reversible. The museum is a place where the asymmetrical war between the ordinary human gaze and the technologically armed gaze not only takes place, but also becomes revealed—so that it can be thematized and critically theorized.

Richard Wagner, The Art-Work of the Future and Other Works, trans. W. Ashton Ellis (Lincoln, NE: Bison Books, 1993), 94.

Ibid., 199.

Ibid., 201.

Kazimir Malevich, “On the Museum,” in Kazimir Malevich, Essays on Art, vol. 1 (New York: George Wittenborn, 1971), 68–72.

Category

Subject

This text was originally presented as a lecture at Museo Reina Sophia, November 8, 2013.

.jpg,1600)

.jpg,1200)