More than a decade ago, I would have found the idea of a forensic institute to be rather abhorrent. Coming from the field of left activism and critical spatial practice, I felt instinctively oriented against the authority of established truths. Forensics relies on technical expertise in normative and legal frameworks, and smacks full of institutional authority. It is, after all, one of the fundamental arts of the state, the privilege of its agencies: the police, the secret services, or the military. Today, counter-intuitively perhaps, I find myself running Forensic Architecture, a group of architects, filmmakers, coders, and journalists which operates as a forensic agency and makes evidence public in different forums such as the media, courts, truth commissions, and cultural venues.

This reorientation of my thought practice was a response to changes in the texture of our present and to the nature of contemporary conflict. An evolving information and media environment enables authoritarian states to manipulate and distort facts about their crimes, but it also offers new techniques with which civil society groups can invert the forensic gaze and monitor them. This is what we call counter-forensics.1

We do not yet have a satisfactory name for the new reactionary forces—a combination of digital racism, ultra-nationalism, self-victimhood, and conspiracism—that have taken hold across the world and become manifest in countries such as Russia, Poland, Hungary, Britain, Italy, Brazil, the US, and Israel, where I most closely experienced them. These forces have made the obscuring, blurring, manipulation, and distortion of facts their trademark. Whatever form of reality-denial “post truth” is, it is not simply about lying. Lying in politics is sometimes necessary. Deception, after all, has always been part of the toolbox of statecraft, and there might not be more of it now than in previous times.2 The defining characteristics of our era might thus not be an extraordinary dissemination of untruths, but rather, ongoing attacks against the institutional authorities that buttress facts: government experts, universities, science laboratories, mainstream media, and the judiciary.

Because questioning the authority of state institutions is also what counter-forensics is about—we seek to expose police and military cover-ups, government lies, and instances in which the legal system has been aligned against state victims—we must distinguish it from the tactics of those political forces mentioned above.

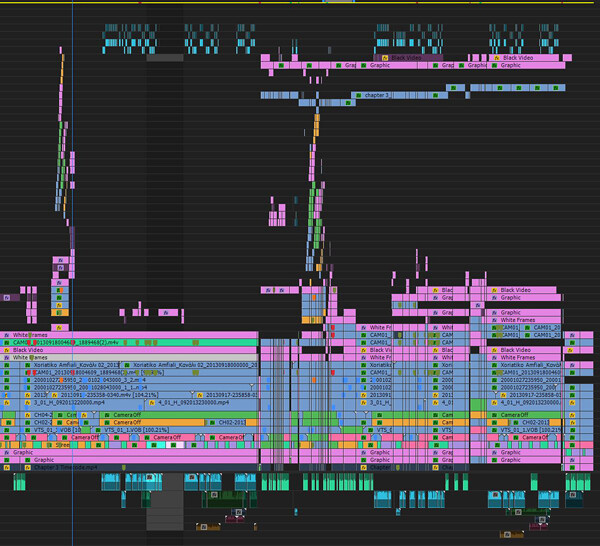

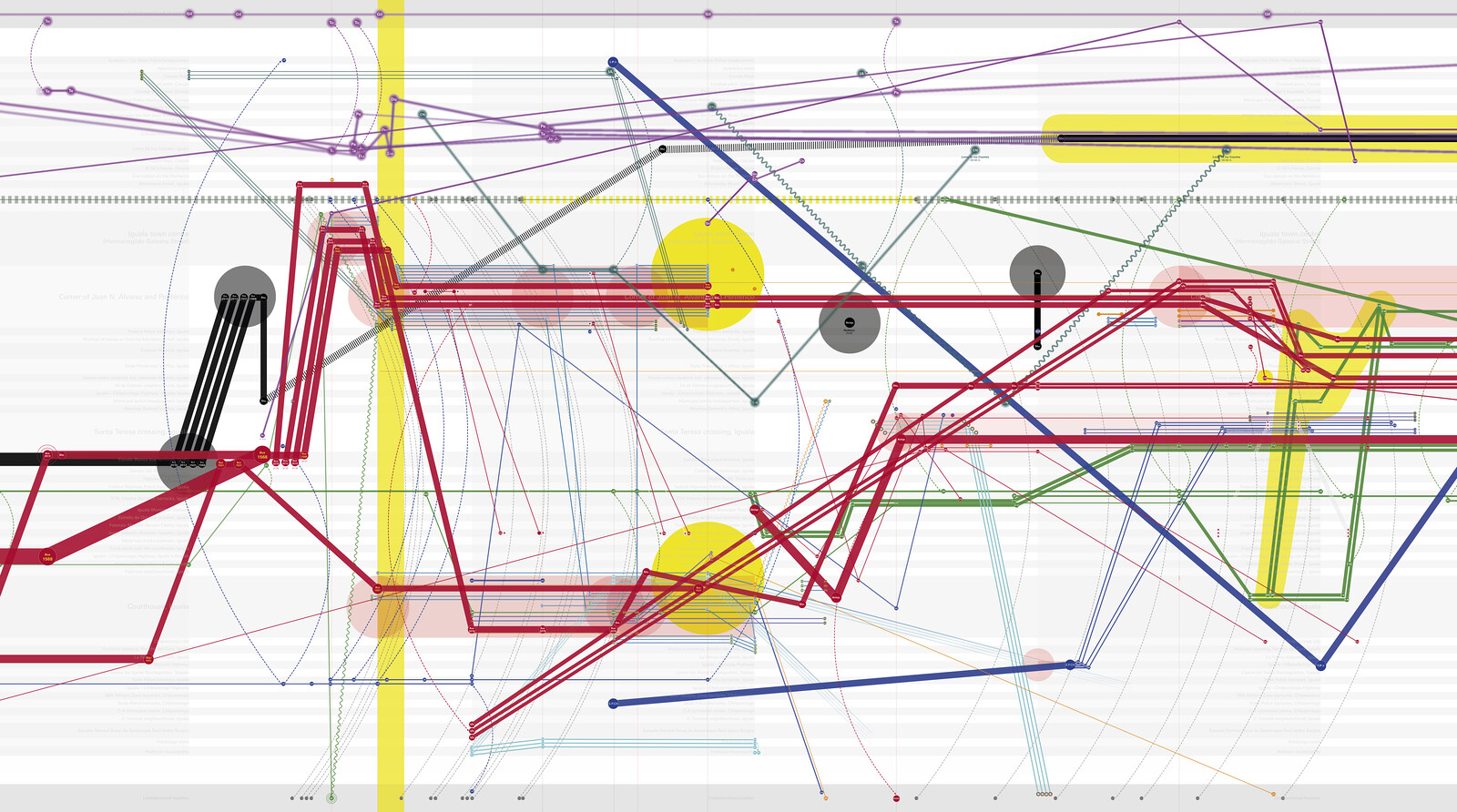

Forensic Architecture, The Murder of Pavlos Fyssas, 2018. A young Greek rapper was killed by Golden Dawn in September 2013. Forensic Architecture showed that police testimonies about it are inconsistent. This image is from the video editing software used in this investigation, showing the synchronisation of the necessary files to suggest police over-up: dozens of videos derived from CCTV cameras and police communications.

Dark Epistemology

While “post truth” is a seemingly new phenomenon, for those working to expose state crimes at the frontiers of contemporary conflicts, it has long been the constant condition of our work. As a set of operations, this form of denial compounds the traditional roles of propaganda and censorship. It is propaganda because it is concerned with statements released by states to affect the thoughts and conducts of publics. It is not the traditional form of propaganda though, framed in the context of a confrontation between blocs and ideologies. It does not aim to persuade or tell you anything, nor does it seek to promote the assumed merits of one system over the other—equality vs. freedom or east vs. west—but rather to blur perception so that nobody knows what is real anymore.3 The aim is that when people no longer know what to think, how to establish facts, or when to trust them, those in power can fill this void by whatever they want to fill it with.

“Post truth” also functions as a new form of censorship because it blocks one’s ability to evaluate and debate facts. In the face of governments’ increasing difficulties in cutting data out of circulation and in suppressing political discourse, it adds rather than subtracts, augmenting the level of noise in a deliberate maneuver to divert attention.

One of the origins of this strategy lies in big tobacco manufacturers. In the 1970s, as the denial of health risks associated with smoking was becoming untenable in the face of mounting scientific evidence of tobacco’s carcinogenic effects, manufacturers created a “smoke screen” of confusion and doubt. Tobacco-funded research groups started releasing a dizzying amount of counter-studies in a scattershot approach that tried to discredit scientific work and mobilize a narrative of distrust without ever offering a coherent narrative in its place.4

The negationism of “post truth” is not an epistemological argument about facts and how best to establish them, but an attempt to cast doubt over the very possibility of there being any way to reliably establish them at all. It is, in the words of several commentators, a dark epistemology, seeking to mask rather than reveal information.5

The strategy of dark epistemologists might seem like a new feature in the political landscape, but it is similar to that of the fascists of old, with their inclination for the “negation” of historical facts of past genocides and present persecutions (which are often connected). The arch-negationist Robert Faurisson rejected historical accounts of the Holocaust by finding and amplifying minor inconsistencies in historical documents—a feature of all archival records—to create what he hoped would become a generalized doubt about whether it happened at all. Philosopher Jean-François Lyotard referred to this negation as an earthquake so strong that it destroys not only the environment—the ground, buildings or roads—but the instruments designed to record its existence and magnitude.6 Authoritarian and totalitarian regimes have an inherent fear of facts because they seek to harness a disordered reality into simplified perceptual frames.

Negation is a particular kind of rhetorical act. It is not only an intervention into the field of political representation, but is entangled with the very violations it seeks to mask. Just like hate speech, it is an act of violence in itself, and the precondition for it to continue. When nothing has happened, or when crimes are not recognized as wrong, violence can be continuously perpetrated.

The political art of dark epistemology has always manifested itself is at the frontiers of contemporary conflicts. In Israel, for instance, the official and recently-state-sanctioned negation of the Nakba—the ongoing expulsion of Palestinians from areas controlled by Israel starting 1948—is the foundation for the almost daily negations of its present violence and human rights violations throughout Palestine.

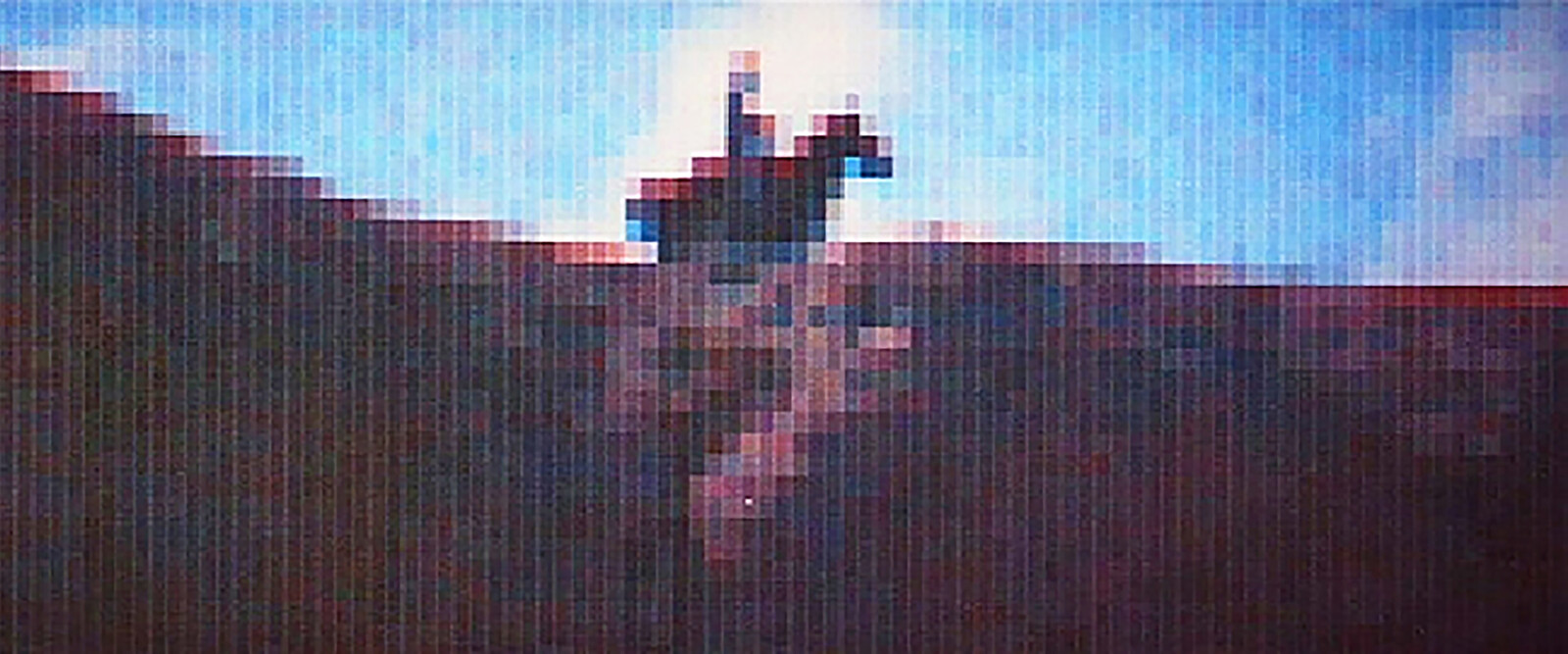

Dark epistemology has also military roots where it has developed its own “operational theories.” Western militaries prefer the terms “psychological operations,” psyops, or “cognitive maneuvering” when describing a campaign for broadcasting misleading and contradictory information to influence people’s conception of reality, emotions, motives, and behavior. Under the labels of “perception management” or dezinformatsiya, Russia and its supporters, have weaponized information of the battlefield, inventing a paranoid, conspiratorial, and hallucinatory reality to divert public attention away from its actions in Syria and Ukraine. In this context, the state violence is aimed at two things: people and things, and the evidence that violence has taken place at all. Perception management in the age of personal media and the internet has become a huge industry, employing troll farms and bot armies. James Harkin of the Centre for Investigative Journalism aptly warned that “the next world war might begin with a grainy, contested image launched online from some distant and inaccessible outpost.”7

The reason people in Western countries have become aware of dark epistemology is because these battlefield techniques of conflict management have only recently beached like a carcass onto the shores of mainstream western politics. Thus, what every human rights activist has been aware of for many years has become visible and marked as the new phenomenon of “post truth.”

Some suggest that current attacks against truth have the flair of liberal or libertarian minority rights and identity politics, or the left philosophy of post-structuralism which identifies established truths, science, enlightenment values, and common sense as the product of power relations and as a means of domination. Indeed, some promoters of dark epistemology have referred in passing to the cultural heroes of post-structuralism, something that led, here and there, people to blame post-structuralism for these ills of our present.8 I think, however, that in resisting dark epistemology we need to do something more subtle than either turn our rage against deconstruction, or revert to a known position of last resort: defending the positivism of old with its established guardians of power/knowledge.

Rather, a critical approach is essential for the two main things counter-forensics needs to do: deconstructing false statements made by officials and reconstructing (something of) the truth of what has happened. Post-structuralism’s culture of suspicion is essential in exposing the gaps, inconsistencies, biases, traces of manipulation, and misrepresentations in the statements of those in power or in places where the habit of trust might otherwise compel us to see facts. A critical approach is essential to understand the circumstances and modes by which official statements are made and to find inconsistencies and lacunae within them. But such a critical approach can also have a constructive function. When we understand how facts are made, where their weaknesses lie, and what are the limits of what can be said, we can better construct and defend them.

Polyperspectivity

The attacks on traditional institutions and expertise that have so often been made in the context of the current nationalist, racist insurgency have never provided the basis for the production of counter-hegemonic knowledge.

Instead of rejecting the current challenges to institutional authority and expertise, the moment of “post truth” could give rise to an alternative set of truth practices that can challenge both the dark epistemology of the present as well as traditional notions of truth production.

It might be altogether necessary to employ the word “truth” differently. In opposition to the single perspectival, a priori, sometimes transcendent conception of truth embodied by the Latin word veritas—which connotes the authority of an expert working within a well-established discipline—a term more suitable to our work and of the same root is verification. Verification relates to truth not as a noun or as an essence, but as a practice, one that is contingent, collective, and poly-perspectival.

The term verification could itself be associated with scientific authority. It originally belongs to the theory of science. It charges empirical observation with the task of confirming or falsifying an abstract proposition, be it a mathematical model, scientific theory, or philosophical conjecture. In the field of journalism, verification confirms or falsifies the statements of governments, politicians, corporate spokespersons, and the like. But it could also be opened up to engage with new kinds of material—open-source and activist-produced—and employ different methodological processes that open and socialize the production of evidence, integrate scientific with aesthetic sensibilities, and work across and bring together different types of seemingly incompatible institutions and forms of knowledge.

The texture of the present is defined by a groundswell of online data which is full of raw information, but also disinformation, noise, bias, and distortion. Open-source investigations fish in these seas. Its methods deal with the collection and analysis of material found online or in other publicly available sources, and can sometimes also include content that is leaked or obtained by freedom of information requests. They are loosely based on the culture of open-source code, where work is undertaken in a diffuse manner and contributed to by a network of like-minded practitioners using the internet.

The CIA policy of extraordinary rendition, for example, was exposed by open-source investigators who collected and connected seemingly mundane bits of information—private jet flight paths and receipts and addresses from places like Latvia, Romania, and Djibouti.9 Similarly, covert Russian military presence in Ukraine was exposed by local and remote citizen-investigators working together, filming, collecting, corroborating, geolocating, and cross-referencing material that connected the dots and confirmed the Russian military’s presence on the ground.10

The first stage in the process of open-source investigation is determining the authenticity and provenance of contested documents. While verification refers to an event, authentication refers to a single piece of evidence—say, a video or audio file—and establishes whether it has been tampered with. This is an essential in the era of “deepfakes,” when image manipulation technologies outpace technologies of detection. Authentication has both vertical and horizontal dimensions. The vertical dimension is concerned with deep investigation of the file in question—the composition of compressed pixels could testify for tampering.11 Horizontal authentication is based on establishing lateral relations between scattered evidentiary sources.

When an incident or accident takes place, multiple videos are often shot simultaneously by different people in different locations, each one offering a different perspective and focus. Not all found videos appear important or relevant at first glance, but they might contain information or provide important links, like connectors or time-anchors between other videos.

Patiently adding different local, ground-level perspectives to one another allows us to investigate incidents from different points of view. Most users point their cameras in the direction of the destruction and its victims, yet some know to seek with their cameras the perpetrators, capturing insignia, weapons, vehicles, or aircrafts.12 The more perspectives, the more relations can be established between the actors, perpetrators, victims, and bystanders in a scene. When videos can be linked to each other, the risk of an inauthentic video is also reduced.13 When a video is authentic it will more easily link with others, whereas a fake video will often remain an outlier.

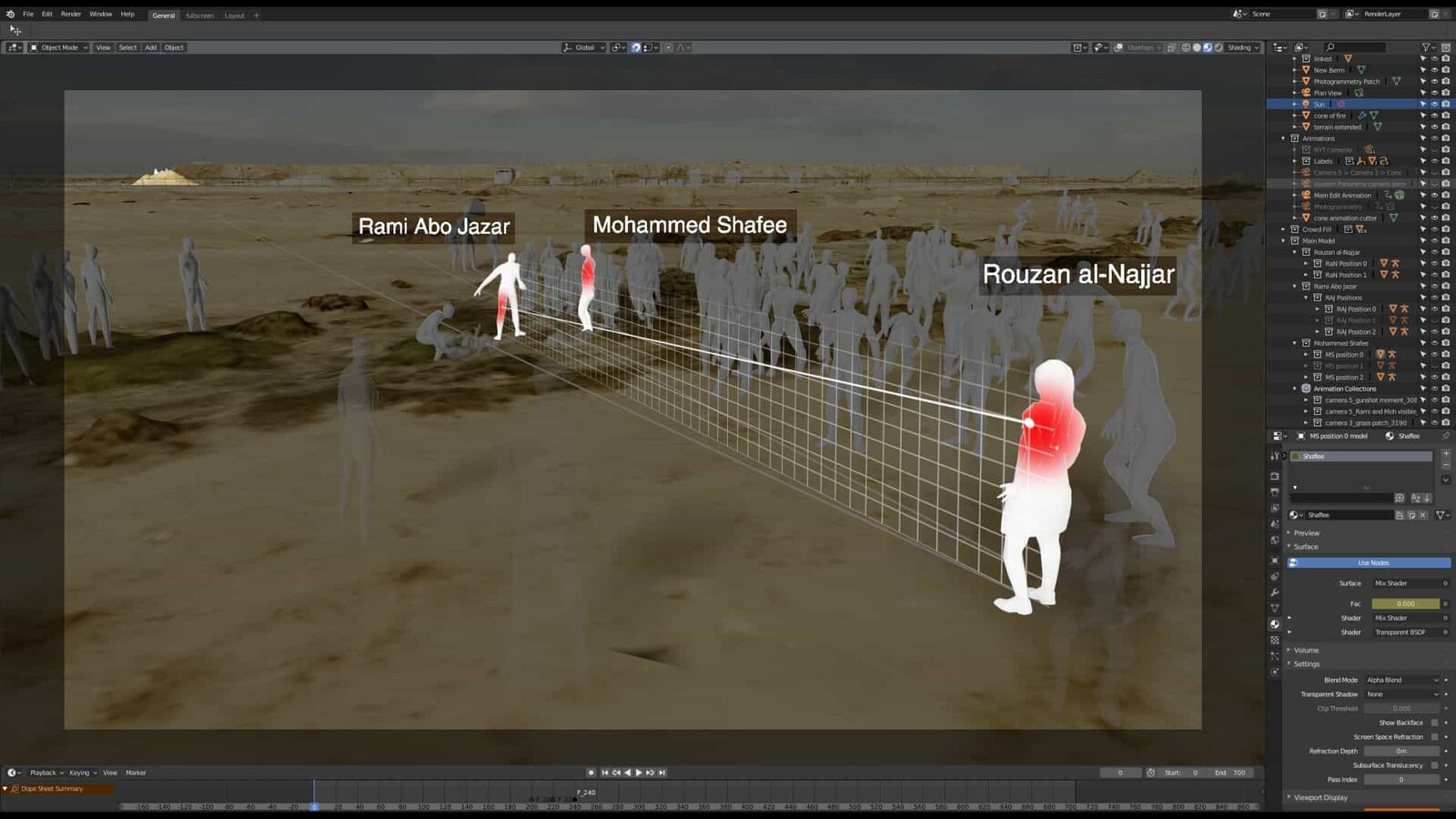

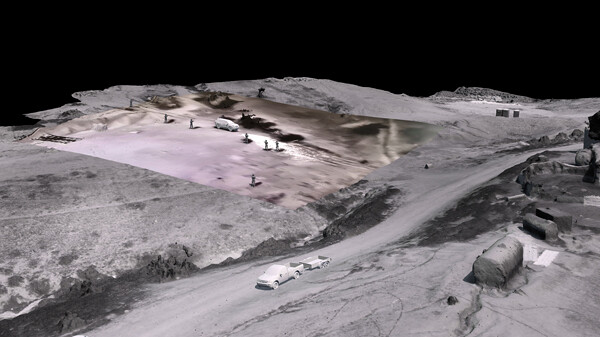

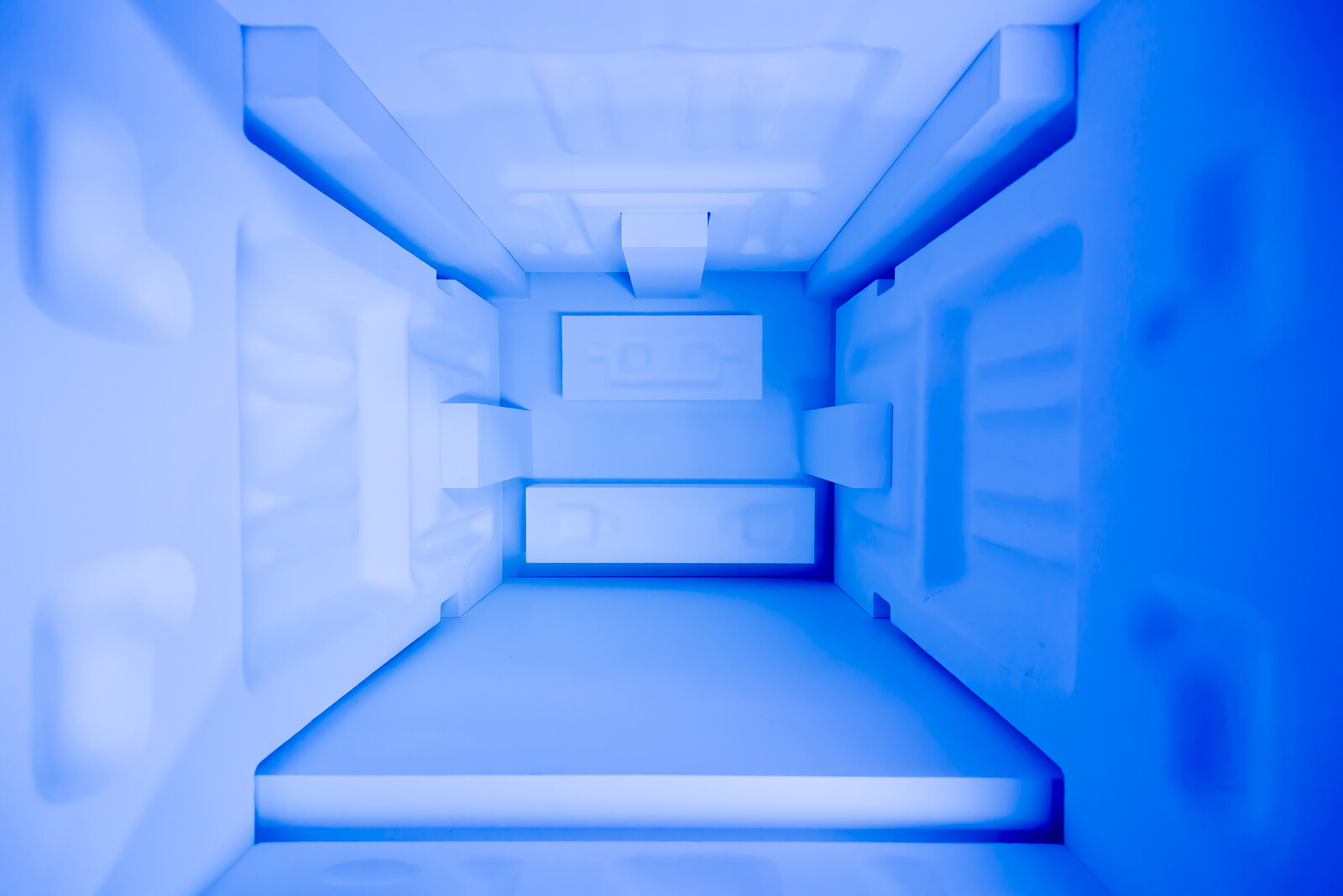

Forensic Architecture, The Killing of Rouzan al-Najjar, 2019. Twenty-year-old medic Rouzan al-Najjar was shot and killed by an Israeli sniper on June 1, 2018, during a protest at a site near Khan Yunis, Gaza. Forensic Architecture synchronised the available footage and plotted the movement of each camera to model the position of individuals and establish a likely ”cone of fire.”

Forensic Architecture, The Killing of Rouzan al-Najjar, 2019.

Forensic Architecture, The Killing of Rouzan al-Najjar, 2019.

Forensic Architecture, The Killing of Rouzan al-Najjar, 2019. Twenty-year-old medic Rouzan al-Najjar was shot and killed by an Israeli sniper on June 1, 2018, during a protest at a site near Khan Yunis, Gaza. Forensic Architecture synchronised the available footage and plotted the movement of each camera to model the position of individuals and establish a likely ”cone of fire.”

At Forensic Architecture, we use 3D models as dynamic digital environments to locate cameras and other media artifacts. Because most videos and images found online are without metadata, they need to be geolocated within what we call “operative models.”14 These models also allows for the time of the image to be determined by simulating shadows and matching them with those captured in images, or by mapping the movement of clouds.

Within these models, the camera’s cone of vision is inverted; images and videos are projected outwards from the camera until the features of the image match the massing details of the model. Once the calibration of one image or video into the model has been achieved, other sources can be matched more accurately. The more videos or images within the model, the more complete our view of the event is. The operative model then allows investigators to spatially and temporally move between image and video sources. The way of handling and viewing moving images is thus one of spatial navigation, rather than the traditional approach of splice and edit.

Open-source investigators are sometimes accused of being remote from the subject of their analysis. But personal cameras and the internet bring investigators to experience events from the perspective of witnesses who have immediate access to events. Many people documenting atrocities do so at the risk of their lives; they find ways to film and upload material when doing so can get them shot and when authoritarian regimes make entire areas electronically inaccessible.

However, the fact that not all places are equally networked is a limit to open-source investigations, whose attention could tend to gravitate towards the places most documented. Furthermore, the absence of videos could itself be evidence for violations. Internet shutdowns often correlate with state violations, as the currently escalating situation in Sudan demonstrates. Cameras could be seized by police and militaries, journalists targeted, and online data removed. In such situations, testimonies of witnesses and material traces are the only available resource.

Open verification must therefore collapse the distance of open-source analysis with the proximity of direct engagement with communities on the ground, and establish personal contact with the people and communities exposed to violence. Forensic Architecture has over the years developed methods of analysis that includes interviewing witnesses within virtual models, helping some retrieve lost memories.15 The analogue dimensions of open verification include site visits and material analysis. But importantly, it also requires the establishing of contact, remote or proximate, with witnesses who experienced the violence first-hand. Local perspectives can then be brought together with scientific expertise—such as blast, fire, or fluid dynamics, or in the case of environmental issues, remote sensing, botany, and geology.

Open verification shifts back and forth between closeups and extremely long shots, moving transversally and laterally between different source points, perspectives, and world-views. It relies upon the creation of a community of practice in which the production of an investigation is socialized; a relation between people who experience violence, activists who take their side, a diffused network of open-source investigators, scientists and other experts who explore what happened. The presentation of evidence must also be socialised with lawyers, journalists, and sometimes, in our case, cultural institutions that help fund, produce, and present the work. As such, the open process of the investigation establishes a social contract that includes all the participants in the uncanny assemblage of production and dissemination. Every case produced with open verification is thus not only evidence of what has happened, but also evidence of the social relations which made it possible.

Forensic Architecture, Killing in Umm al Hiran, 2018. Shortly before dawn on January 18, 2017, a large Israeli police force raided the Bedouin village of Umm al-Hiran in the Naqab/Negev Desert in order to demolish several houses. Two people were killed: a Bedouin villager, Yaqub Musa Abu al-Qi’an, and an Israeli policeman, Erez Levi. Shortly after the incident, the Israeli government and police claimed the incident was a “terror attack” by Abu al-Qi’an. Forensic Architecture spoke to witnesses, undertook a full re-enactment and synchronised videos shot by activists on the ground with thermal imaging camera of a police helicopter overhead, to uncover the true story: Abu al-Qi’an lost control of his vehicle and ran over Levi only after being shot by Israeli policemen, and was subsequently left to bleed out and die. This analysis forced the police to retract its narrative of the incident.

Our investigation into the murder of Yakub Musa Abu al-Qi’an in the village of Umm al-Hiran in the Naqab/Negev, for instance, was carried out in collaboration with the residents of the village, activists on the ground such as Activestills videographers, Palestinian politicians who were present in solidarity, alternative and mainstream media organisations, human rights lawyers, and even a retired policeman that was happy to share of detail of police process. It was the variety and strength of this network that ultimately led state officials to retract their narrative that Abu al-Qi’an was a terrorist.16

Open verification has less access to the privilege of institutionalized truth practices, whose claims are often backed only by the authority of their respectable façades which can hide the hard and messy work of case construction. We can never take trust for granted. While the probity of traditional expert testimony—when presented outside of scientific forums and to the general public—lies in the credentials and reputation of scientists or their institutions, the probity of open verification must be in its making. The burden of open verification is to gain trust and keep as open and transparent as possible the processes by which truth claims are made and facts established. Open verification needs to continuously expose every step by which the work was carried out, its circumstances, the people involved, the materials used, how and where each piece of evidentiary material was found, its modes of authentication, the ways by which different pieces of evidence were brought together, and a case was assembled. Doing this allows for the public domain to function in an analogous process to a scientific peer-review; that is, for the underlying data to be examined by others, and the processes to be replicated and tested. This is the reason that most of the content of our video investigations is a “how-to.” The presentation of a case thus always needs to record the interaction and interference that were part of its process.17

This openness is necessary because, unlike medical or DNA experts, the basic building blocks of these cases—images, videos, material remains, or testimonies—and how they are assembled, must also be understood by non-experts. Following the root of the word in the Latin forum, forensics is about making evidence public, and thus political. Beyond the exposure of our methods and the amount of information woven together, open verification must be persuasive through the force of its narrative, the momentum of its collectivity, and the rhetoric of its presentation in image, video, text and sound. To make a change it needs to be mobilized as part of a social-political process, and for this, social alliances need to be built.

Contaminated Knowledge

Dark epistemologists do not only attack the old state institutions of authority but also organizations like ours who expose the powers they seek to protect. They do it by targeting precisely what makes open verification possible: its composed and networked dimension. A single video showing a perpetrator and its victim in the same frame is always going to be more convincing than the synchronisation of a dozen or more videos and their composition into a 3D model. While for us the strength of evidence is the degree to which it is composed and its different elements support each other, it is precisely this complexity of composition that is attacked by those whose actions we intend to incriminate. They act as if each individual piece of evidence must in itself be proof of the crime as a whole. The more steps a source material is taken through—the more varied the sources in the mix and people involved—the more those accused cry manipulation, fabrication, aestheticization. Every defense lawyer will always seek to find weak links in the evidence against their client, but here it seems that what is being targeted is the very idea that evidence requires different elements and the synchronized work of multiple practitioners.

Given the collaborative and composite nature of open verification, denialist organizations have adopted other tactics to work against it. Sometimes it involves scanning through the diffused network necessary to produce facts to identify what might be referred to as the “contaminating factor.” The contaminating factor could be human or not: a person, an organization, a political affiliation, a video, or even a funder whose identity might be vulnerable to attack. Denialists then claim that by association, the entire network and the information it produces is tainted and meaningless.

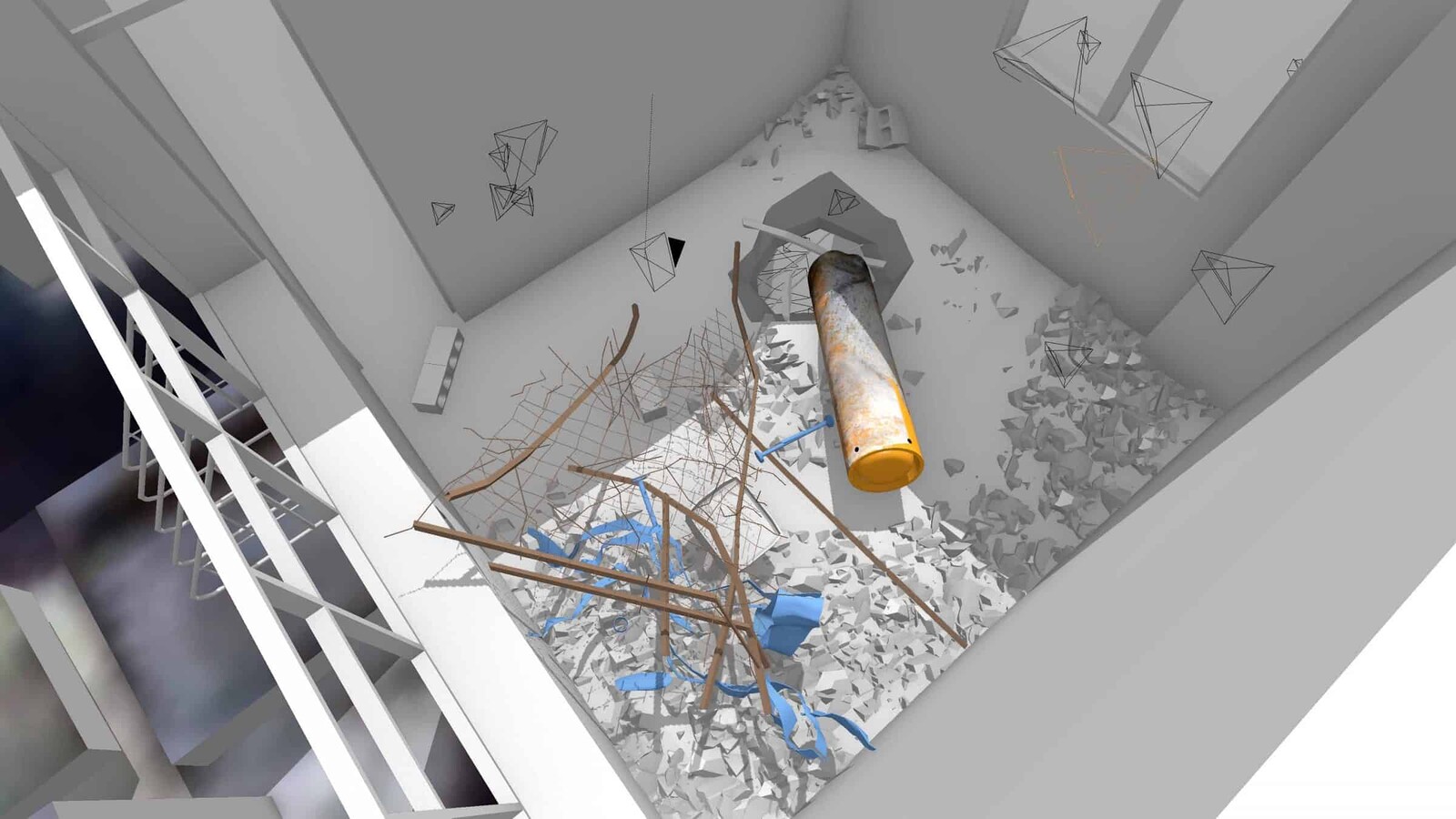

In 2016, we investigated Russian air-force strikes on an MSF (Doctors without Borders) supported hospital in Syria. The case was carried out by combining testimony from Syrian civilians and physicians at the scene, synchronizing and locating multiple videos shot by the first responders of the White Helmets, and corroborating these with recorded sightings of Russian fighter jets taking off and landing just before and after the attack, as well as with statements made by the Russian air force.18 In response to the publication of our findings, RT, one of Russia’s main English-speaking, state-sponsored media (i.e. propaganda) channels, attacked our analysis by stating that using material uploaded by the White Helmets—which they claimed were elsewhere involved in providing medical aid to terrorists—and the west-funded Syrian Observatory, made our claims worthless.19 But open verification considers all available sources, including those of the belligerents themselves, acknowledging the partial and often tendential ways in which it was recorded and disseminated, and after authenticating each piece of evidence, engages in composing them together to see if a story emerges. The more perspectives the better, obviously, but the more they come from different and antagonistic sources the better too. Our attitude to evidence is “respect and suspect,” and our guiding questions are “is it authentic?” and “does it link up?”

Also in 2016, we investigated the Syrian government’s most notorious prison of Saydnaya with Amnesty International. We cross-referenced the testimony of five of its survivors by virtually placing them within an architectural and acoustic model of the prison. The investigation was widely disseminated and led to general condemnation of the regime. Pressed about the result of this investigation, president Assad falsely claimed it was “funded by Qatar… to smear the Syrian government.”20 Others go after our OSF funding, the often-vilified organization founded by George Soros (no funder has any say over our selection of cases or finds).

Other contaminating factors could be the images themselves. Perpetrators often claim that image quality is too raw, grainy, blurry, or shaky to conclusively show they violated human rights. Israel makes US satellite providers degrade the resolution of available images over the country and its occupied territories, where most of its violations occur, and then often claims that satellite surveys of the destruction it brings about in Gaza are unverifiable.21

At other times, the designation of an investigation as an “artwork” functions as the contaminating factor. When we published our investigation that called into question the testimony of a German Secret Service (Verfassungsschutz) agent who claimed he did not witness a neo-Nazi murder in 2006—despite being present at the crime scene during the incident—members of the Christian Democratic Party (CDU) in charge of the Verfassungsschutz applied a similar negationist tactic. Looking through the bios of our team members, they picked those of us who graduated from art schools and, together with the fact that the investigation was shown in Documenta 14, claimed that we were “merely artists,” and thus unqualified to produce evidence.

Forensic Architecture, The Enforced Disappearance of the Ayotzinapa Students, 2017. Mexican investigative journalist and FA team member Irving Huerta narrates to the mural at MUAC in Mexico City.

Aesthetic Commons

Rather than putting aesthetics in a separate place or even in opposition to knowledge production, we need to find new ways of aligning them. As the capacity to sense and detect, aesthetics has an obvious evidentiary dimension.22 It is also essential as the mode and means for narration, performance, and staging necessary for making evidence public. And it is evident that, when it is mainly images and videos that need to be examined, image producers—photographers and filmmakers— have a crucial role to play.

Exhibitions in art and cultural venues could act as forums complementary, and sometimes even alternative to legal process. This is particularly necessary when evidence of the kind we produce is not admitted to court, or when juridical processes function like rabbit-holes, disappearing cases for years. The presentation of the NSU investigation in Documenta was in fact useful in making public its results. Being seen by hundreds of thousands of people led to the work’s invitation to a German Parliamentary commission of inquiry where Andreas Temme—the secret service agent whose testimony we found to be a lie—was required, despite his protests and that of the CDU delegation, to watch and respond to a screening of the “art work”. Indeed, as this case taught us, integrating cultural and aesthetic practices within the investigative process could contribute to changes in the role of both art and law. We both use cultural institutions as forensic forums and act curatorially and performatively within legal ones.23

Collaborations with cultural and art venues are useful in other ways too. Museums and biennales have helped produce new work. For example, the follow-up investigation to the NSU case, concerning police involvement in the killing of the anti-fascist-rapper Pavlos Fyssas by Golden Dawn members in Athens, was co-produced by BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, in Utrecht.24 Our ability to return to and open up the case of the Israeli police killing of Yakub al-Qi’an and its cover up, was made possible with the budget provided for an exhibition at Tate Britain. It is ironic to notice how, as the art of lying spreads through institutions of power, the craft of truth must find its place in the museum.

Collaborating with art and cultural venues is not only a pragmatic move. Both forensics and curatorial practices share a deep concern for knowledge production and display, for the presentation of ideas and issues through the arrangements of evidence, objects, conversations, screenings, or bodies in space.25

On one recent occasion, our work in the domain of art and in that of human rights were brought together. Late in 2018 it became known that the tear gas canisters used by the Israeli army against protesters in Palestine and by US agencies against both protestors in Ferguson and migrants in Tijuana-San Diego border were manufactured by a company owned by Warren B. Kanders, the vice chair of the board of trustees of the Whitney Museum of American Art. The museum invited us to take part in the 2019 iteration of its biennale. This required a different approach, and our work, Triple-Chaser, with Laura Poitras, presented an investigation of Kanders’s weapon business at the Whitney, and even lead to the issuing of a legal notice against him.26

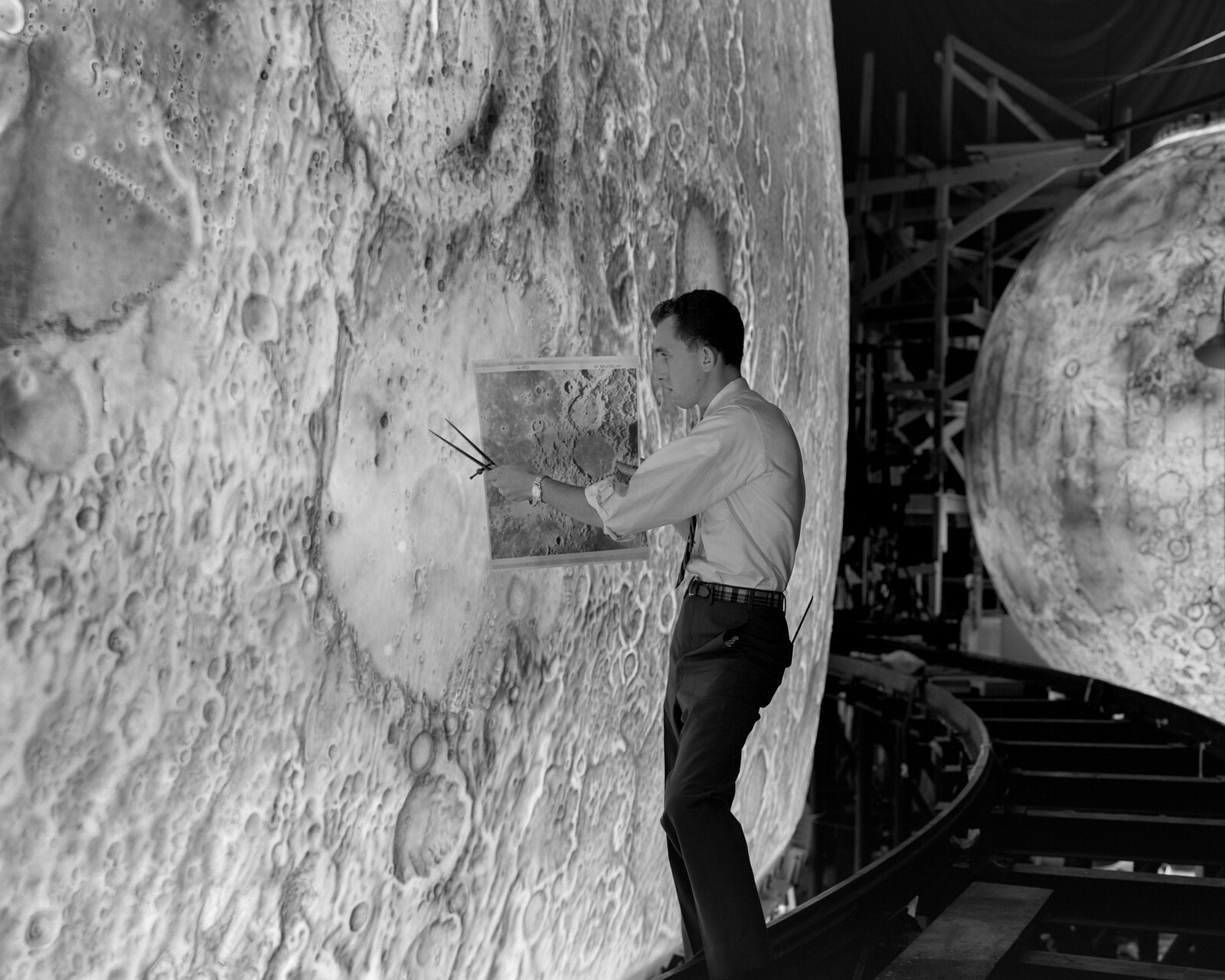

The meshing of legal, scientific, and aesthetic practice has a long history. A close entanglement of visual art, architecture, and science can be traced back to early modern Europe. In the sixteenth century, knowledge about nature was produced by practitioners who occupied a liminal space between science and art.27 The European art academies of the following century provided artists with access to experts on anatomy and the techniques of linear perspective and anamorphic projection. But gradually, the shared epistemology and aesthetics of facts started diverging into separate subjects and specialisms, such that by the nineteenth century the domains of science and art were positioned in opposition to one another. The scientific virtue of objectivity has purportedly become unresolvable with the aesthetic virtue of subjectivity. While a scientist was asked to restrain all individual, situated, and unique traits or character, an artist was required to augment them. Objectivity aspired to be, in the words of Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison, a “form of knowledge that bears no trace of the knower.”28 In keeping with this reductive separation, it was these “traces of the knower” that were precisely what our critics would refer to as “contamination.” But for us, situatedness is the defining feature of the very notion of evidence.

Today this gulf between science and art must close again. The practice of open verification is one of the avenues through which to re-entangle artistic and scientific work and bring forth a new aesthetic of facts. Rather than objectivity’s “view from nowhere,” open verification seeks the meshing of multiple, subjective, located, and situated perspectives. Rather than being confined to the black boxes of institutions of authority it is based on open processes and new alignments between different sites and institutions of diverse types and standings: the science laboratory, the artist studio, the university, activist organizations, victim groups, national and international legal forums, the media, and cultural institutions.

So while there might seem to be an apparent, superficial link between “post truth” and our practice of counter-forensics—both approaches question statements made by government agencies like the police, intelligence services, and the court—there is also a crucial difference.29 We respond to the current skepticism towards expertise not with resignation or a relativism of anything goes, but with a more vital and risky form of truth production, based on establishing an expanded assemblage of practices that incorporate aesthetic and scientific sensibilities and includes both new and traditional institutions.

State perpetrators and dark epistemologists want to destroy the possibility of a common ground. And so, without a state to protect and guide us, establishing the common ground becomes a political project. With each new investigation, a new community of praxis is woven from the meshing of its divergent viewpoints. In this, open verification becomes a form of construction. In socializing the production and dissemination of evidence, it ultimately establishes an unlikely but fundamental commons in which the production facts constitute the foundation of an expanded epistemic community of practice built around a shared perception and understanding of the world.

The struggle for a common ground is an essential meta-political condition: a precondition for any political initiative and struggle to take place. This commons might seem analogous to a natural resource such as air or a freshwater, and as such we must protect it when it is polluted by the toxins of dark epistemologists. Yet unlike water and air, it is neither pre-existing nor natural, but a social reality that needs to be continuously remade, reinforced and fought over. It must not be fenced off, but kept with its margins open to new information and ever-newer perspectives, evidence, and interpretation. As such it can only grow and morph with disagreement.30

The term has been first proposed by Alan Sekula. See: Thomas Keenan, “Counter-forensics and Photography,” Grey Room 55 (Spring 2014): 58–77. The term first appeared in Allan Sekula, “Photography and the Limits of National Identity,” Culturefront 2.3 (Fall 1993): 54–55.

In her essay on lying in politics, Hannah Arendt writes: “deception, the deliberate falsehood and the outright lie used as legitimate means to achieve political ends, have been with us since the beginning of recorded history. Truthfulness has never been counted among the political virtues, and lies have always been regarded as justifiable tools in political dealings.” Hannah Arendt, Crises of the Republic: Lying in politics, Civil disobedience, On violence, Thoughts on politics and revolution (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972), 4 and 45. For a short extract of Arendt’s essay in the New York Review of Books, see ➝.

An interesting presentation of this can be found in Metahaven’s Eurasia: Questions of Happiness (2018).

In 1976, the American tobacco conglomerate, Philip Morris, released a public statement to a growing evidence base on the health effects of smoking: “none of the things which have been found in tobacco smoke are at concentrations which can be considered harmful. Anything can be considered harmful. Apple sauce is harmful if you get too much of it.” “Tobacco Explained: The truth about the tobacco industry… in its own words,” World Health Organisation, November 2018, ➝.

See Rick Searle “How dark epistemology explains the rise of Donald Trump,” IEET, March 7, 2016, ➝; Michael Adrien Peters, “Anxieties of Knowing,” Educational Philosophy and Theory 46, no. 10 (2014): 1093–1097, ➝, Eliezer Yudkowsky, “Dark Side Epistemology,” LESSWRONG, October 18, 2008, ➝, and Jesse McWilliams “Dark epistemology: An assessment of philosophical trends in the black metal music of Mayhem,” Metal Music Studies 1, no. 1 (October 2014): 25–38, ➝.

“Suppose that an earthquake destroys not only lives, buildings, and objects but also the instruments used to measure earthquakes directly and indirectly.” Jean-Francois Lyotard, The Differend: Phrases in Dispute (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989), 56.

James Harkin, “What Happened In Douma? Searching For Facts In The Fog Of Syria’s Propaganda War,” The Intercept, February 9 2019, ➝.

Philip Rucker and Robert Costa, “Bannon vows a daily fight for ‘deconstruction of the administrative state’,” Washington Post, February 23, 2017, ➝.

See Trevor Paglen, and AC Thompson, Torture Taxi: On the Trail of the CIA’s Rendition Flights (New York: Melville House, 2006). See also Edmund Clark and Crofton Black, “Negative Publicity: Artefacts of Extraordinary Rendition,” (Magnum Foundation, 2016), ➝.

The investigations of Forensic Architecture, Bellingcat and Truth Hounds, a Ukrainian human rights monitoring group are explored in further depth in Oliver Hahn and Florian Stalph, eds., Digital Investigative Journalism: Data, Visual Analytics and Innovative Methodologies in International Reporting (Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 150.

For example: most images online are the standard .jpg format. .jpg is a form of compression that reduces the size of an image by finding commonalities between pixels, but every camera does this slightly differently. Looking for deviations might help find out whether and which pixels have been shifted or manipulated. Much of the vertical authentication work taking place today is now being delegated to machine learning algorithms.

Rebecca J. Hamilton, “User-Generated Evidence,” Columbia Journal of Transnational Law 57, no. 1, 2018.

The International Criminal Court in The Hague ICC is increasingly moving towards multimediality and open source evidence and verification in its prosecutive work. See Emma Irving, “And so it begins… Social Media evidence in an ICC arrest warrant,” Opinio Juris, August 17, 2017, ➝.

In Forensic Architecture’s work, physical and digital models are more than mere three-dimensional representations of proposed structures—as they are typically used in architectural practice—but rather function as analytical or operative devices. Spatial and non-spatial models provide a theoretical understanding of the way in which particular incidents may have unfolded, or can help make predictions as to how certain situations might develop. Others are used to test, simulate, create, and present evidence. Operative Models, to paraphrase filmmaker Harun Farocki’s concept of “operative images” are entities that not only represent, but “do” things in the world, serving as essential means to construct evidence and assemble a forum around it.

➝.

Haaretz Editorial: “Israel Must Put an End to Bedouin Village Blood Libel”, June 4, 2019, ➝.

When facts are established in this way, they operate somewhat like a contract, not unlike how theorist Ariella Azoulay conceptualized the “civil contract of photography,” as “a virtual political community, that is not dictated by a ruling power, but opens new possibilities for political action, encounter and conditions of visibility between the photographed, photographer and spectator.” Ariella Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography (New York: Zone Books, 2008).

➝.

An interview I gave on Russia Today: Going Underground with Afshin Rattansi, January 25, 2017, captures several of these lines of attack. See also Eliot Higgins, “Russia’s Bizarre, Barely Coherent Defence It Didn’t Bomb Hospitals in Syria,” Bellingcat, February 17, 2016, ➝.

There are a host of Israeli organization that collaborates with Israel’s recent right-nationalist governments to spread doubt, incite hate, and silence civil society and human rights groups critical of the occupation. They claim that holding a critical view of Israel disqualifies one from research on it. For them, my colleagues and I are “obsessive Israel bashers” who manipulate evidence to suit a political aim and smear the Israeli army, often pointing to the petition I signed in 2009 against Israel’s attack on Gaza. To them, this means that no matter which human rights organization or journalistic group we work with, we are not doing anything other than faking evidence. See “Amnesty’s “Gaza Platform”: All Window Dressing, No Substance,” NGO Monitor, July 7, 2015, ➝.

For further reading, see Eyal Weizman and Thomas Keenan, Mengele’s Skull: The Advent of a Forensic Aesthetics (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2012); Eyal Weizman, Forensic Architecture: Violence at the Threshold of Detectability (New York: Zone Books, 2017); and Eyal Weizman and Matt Fuller, Investigative Aesthetics (Verso, forthcoming).

A precedent, suggested to us by Yve-Alain Bois, is Soviet Russia’s Factography, a collective enterprise that, in the 1920’s and 30’s, was geared towards the construction of facts, using technological and scientific methods, information media and graphics, as opposed to merely documenting them. For more on Soviet factography, see: Ingrid Nordgaard, ““In Search of the Present Tense”: Soviet Factography and Collectivism,” NYU Jordan Center for the Advanced Study of Russia, April 6, 2013. ➝; See also Devin Fore, “Soviet Factography: Production Art in an Information Age,” Chto Delat, August 6, 2016, ➝.

Forensic Architecture’s team investigating the murder of Pavlos Fyssas in Athens consisted of Christina Varvia (Project Lead), Stefanos Levidis (Project Coordinator), Simone Rowat (Video Research and Production) Sofia Georgovassili, Fivos Avgerinos Dorette Panagiotopoulou, Nicholas Masterton, Stefan Laxness, Robert Trafford, Sarah Nankivell, Lawrence Abu Hamdan (Sound analysis advisor), Shakeeb Abu Hamdan (Sound analysis advisor), ➝.

Our gratitude to Anselm Franke and Bernd Scherer, Rosario Güiraldes, Cuauhtémoc Medina and Ferran Barenblit, Ayse Gülec, Richard Birkett and Stefan Kalmár, and Maria Hlavajova and Wietske Maas.

➝.

The young Swedish naturalist Carolus Linnaeus is one example of such a figure, whose work was somewhere between a watercolourist and taxonomer, a landscape interpreter and species vault archivist.

Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison, Objectivity (New York: Zone Books, 2010), 17; Pamela H. Smith, The Body of the Artisan: Art and Experience in the Scientific Revolution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006).

➝.

See Isabelle Stengers, “The Cosmopolitical Proposal,” in Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel, eds., Making Things Public (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005), 994–1003.

Becoming Digital is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and Ellie Abrons, McLain Clutter, and Adam Fure of the Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning.

Category

Subject

This text is an edited version of my acceptance speech at the ECF Princess Margriet Award for Culture, and a lecture at BAK, basis voor actuele kunst. My gratitude to Robert Krawczyk for helping with the research, to Nick Axel for the “activist” editing, to Tom Keenan for the comments, and all the amazing researchers at Forensic Architecture: Christina Varvia, Sarah Nankivell , Samaneh Moafi, Ariel Caine, Simone Rowat, Nicholas Masterton, Nathan Su, Stefanos Levidis, Robert Trafford, Lachlan Kermode, Nicholas Zembashi, Martyna Marciniak, Alican Aktürk, Hannah Meszaros-Martin, Susan Schuppli, Lorenzo Pezzani, Shourideh C. Molavi, Paulo Tavares, Francesco Sebregondi, Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Charles Heller, and Başak Ertür.

Becoming Digital is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and Ellie Abrons, McLain Clutter, and Adam Fure of the Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning.

.jpg,1600)