April 10–13, 2014

On its face, the phrase “Silicon Valley Contemporary” seems redundant or even tautological. For decades now the IT industries have pervasively reshaped almost all aspects of daily life on an increasingly global scale. Dinner plans, Hollywood blockbusters, presidential elections––all are now encoded, routed, and delivered to our personal screens. So quickly have we adapted to these new mediations that we easily overlook the extent to which they define our sense of the current situation and our very experience of the present. These developments are so far-reaching that it is hard to merely describe them without succumbing to technological determinism or industry hype.

To residents of the Bay Area, the contemporaneity of Silicon Valley is that much more immediate, inescapable, and controversial. The successive waves of tech industry capitalization—first Apple, then Netscape, then Facebook, Google, and Twitter—have decisively altered the socioeconomic makeup of the region. San Jose, which in living memory was a farm town, is now the tenth largest American city, with six of the nation’s ten most expensive real estate markets located nearby. Rents in San Francisco now rival and even surpass those in Manhattan. Not surprisingly, the speed and scale of these shifts have led to all kinds of backlash: fights in bars about Google Glass etiquette, anti-eviction demonstrations, blockades impeding the private coaches that transport city residents to lucrative jobs in the Valley. Many of these protests reprise familiar themes from gentrification debates elsewhere, and turn in part on the displacement of earlier waves of artists by so-called “creatives.” Other, more radical criticisms concern the extent to which tech start-ups serve as the advance guard of neoliberalization, using the trappings of hipsterism to market the privatization of public services.

Whatever one’s position on these questions, few would argue that Silicon Valley has ever been contemporary when it comes to art. While San Francisco has its share of serious collectors, local consensus has long been that the tech industry is largely indifferent to high culture. Older entrepreneurs prefer to invest in real estate, wine, or design, whereas the Twitter generation tends to put their vested options toward Teslas or luxury RVs for Burning Man. In part, this is the classical dilemma of the nouveaux riches, aggravated by the relative weakness of the San Francisco gallery scene, which has nothing like the blue-chip representation of Los Angeles. It likely also has something to do with the sort of nerd-cred that values an apathy or antipathy toward matters of taste and fashion—a stance epitomized by Mark Zuckerberg’s famous hoodie. No matter the cause, in an area where entrepreneurialism is often prized above all else, the enormous potential of this market could not go unnoticed for long.

Enter Silicon Valley Contemporary: the area’s first-ever contemporary art fair, which boldly sought to advance the cause of culture by making some $100 million worth of art available for purchase, whether through cash, credit, or bitcoin. For the fair’s organizers and participating gallerists, the temptations of this opportunity were offset by the difficulties it presented. Given that much of its intended clientele was ignorant or indifferent, the fair couldn’t simply cater to existing tastes; rather, it had to locate these desires or even create them outright. This quandary led to a certain clumsiness in the event’s PR, such that its messaging seemed to waver between salesmanship and education or outreach; one workshop promised to discern “The Distinction Between Fine Art and Commercial Art.” It seemed that prospective buyers were thought to need a crash course in contemporary aesthetics before they could be persuaded that they weren’t suckers but early adopters, and that their purchases were sufficiently “state of the art,” as the event’s motto put it.

There were three obvious solutions to this problem; like timid investors, the galleries hedged their bets evenly between them. The first approach was to exhibit art that conformed comfortably to the expectations of uninformed or conservative patrons. This meant showing barge-loads of painting and sculpture—much more than one would have expected for a show held opposite the Adobe headquarters. These works covered a full spectrum of conventional styles, from the post-war moment (New York School, neo-Dada) through the 1960s (Op, Pop) through the near past (numerous knockoffs of Gerhard Richter’s abstractions, only some of which were parodic). A surprising amount of this work seemed to come from some parallel universe where modernism never happened. Closer to the present, there was plenty of so-called “street art,” although little that derived from the local Mission School of the 1990s. Much of this could have been curated by the editors of VICE: statues of Kim Jong-un, defaced Disney characters, paintings of skydiving sharks. With perfect predictability, there were sendups of corporate logos (Atari, Apple), paintings of text bubbles, sculptures of QR codes. Any of these could look “critical” in an art magazine, but also perfectly at home in the offices of a start-up.

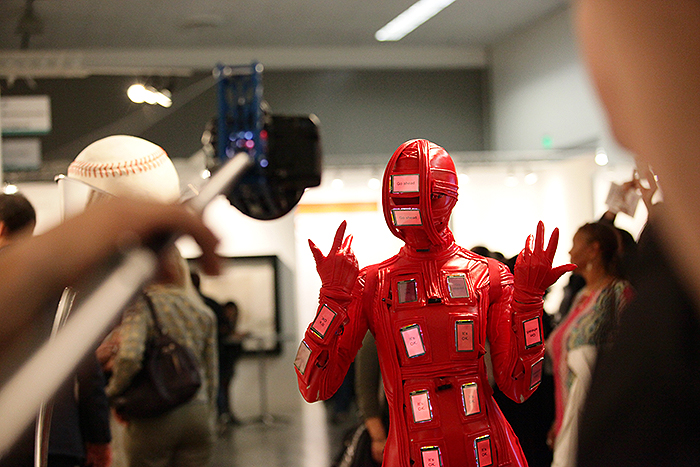

The second sales strategy neatly mirrored the first. Instead of showing familiar work in old mediums, it did the same with new media. Often this meant splitting the difference, as with the many videos that aspired to painterly effects. Some of these, like Jacco Olivier’s BIRD (2011), seen at the booth of New York’s tony Marianne Boesky Gallery, were instantly forgettable; others, like Kate Gilmore’s Rock, Hard, Place (2012) at Miami’s David Castillo Gallery, asked questions about gendered labor that were worthwhile, if not pioneering. One work that succeeded was the late Jeremy Blake’s Winchester Redux (2004) shown by L.A.’s Honor Fraser, not so much because its conception of video as “time-based painting” had cannily anticipated market trends, but because its mythography of San Jose’s supposedly haunted Winchester House injected a doomy note of site-specificity into the otherwise placeless space of the local convention center. Elsewhere, there were few examples of effective media art, whether in video or other, “newer” formats. The one piece that did stand out, if dubiously, was Tiffany Trenda’s Proximity Cinema Performance Documentation, Black Forest, Germany (2013) featured by San Francisco’s The McLoughlin Gallery, for which the artist donned a touch-sensitive suit that recalled a fetish version of a Mighty Morphin Power Ranger; the result, which name-checked VALIE EXPORT’s pivotal Tapp- und Tastkino [Tap and Touch Cinema] (1968), was not the first such re-enactment, but possibly the one to most fully neutralize the trenchant feminism of the original.

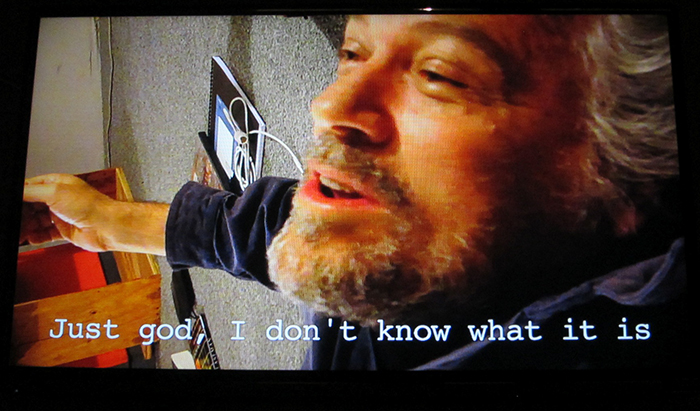

The fair’s third approach was to indulge the time-tested stereotype of the Bay Area as the spiritual homeland of trippy hippies. These appeals ranged from the laughable (an image of Jim Morrison rendered from foil-wrapped pills) to the predictable (holograms, fractals, coyotes, domes, coyotes in domes). Perhaps the most depressing was Gary Hill’s Depth Charge (2009–12), a multi-channel video installation depicting the artist during a recent acid trip. Hill, who was awarded the fair’s first Distinguished Media Artist Award, tries to narrate his experience, only he’s so high that his rambling pseudo-profundities require subtitles. Even transliterated into English, they never get beyond awkward cliché. It’s a pity—some of Hill’s early work remains brilliant and relatively unknown, whereas this piece is like something Rosalind Krauss might have commissioned to illustrate her famous dismissal of video as a narcissistic medium.

Exceptions to these tendencies were few. There was scarcely any art from outside the art school-dealer nexus. For that matter, there was little art from outside the North Atlantic, although that depends a bit on who’s keeping score—one of the more appealing and visually striking works exhibited by New York’s Dillon Gallery, The Afronauts (2012), was produced by the Spanish photographer Cristina de Middel, in a style that regrettably combined racialized exoticism with a condescending retro-futurism. Such missteps left one feeling that the fair was itself a kind of botched mission, and that the entire notion of “Silicon Valley Contemporary” is basically an oxymoron, at least for the foreseeable future. There was no trace of craft, social practice, or any of the issues that concern artists actually working in the Bay Area. Neither was there any sign that artists could critically engage information technologies, as they have since the 1960s and continue to do through hacktivism and any number of other modes. One didn’t even see much of the sort of shallow but trending work produced by the “post-internet” artists loudly championed by art-flippers like Stefan Simchowitz. Instead, like the “clean rooms” in which microprocessors are made, the fair existed in isolation from the messier realities that would have lent it relevance, or at least guaranteed a more reliable product for its end users.