A scene from a likely near future: an architect wakes up to a chirping phone. She sits up and looks at the messages that prompted the noisy wakeup call. Her banking app says she’ll have $500 spending cash this month. It suggests several experiences she can pay for with this money: drone racing in Brooklyn, a walking history tour of modern art in SoHo, or wine tasting in Suffolk county. She makes $200,000 a month, but she hasn’t had this much to play with in a long time. $160,000 a year is gone before it even hits her bank account. Some of it is in taxes, but two-thirds of her annual income goes directly to AliUber—the megacompany that resulted from a series of mergers and acquisitions in the late ‘20s.

Our architect rarely thinks in dollars, euros, or renminbi since most of her purchases are withdrawn from an allowance of credits, which can be redeemed at bars, restaurants, yoga studios, and even the local aquarium. The rest is funneled to other annual subscriptions that are not (yet) controlled by this single company that is also her landlord at home and work, primary source of food, and utility provider.

Our architect does not own or even rent the room she woke up in. The six figures she sends to AliUber, just like the music and movies she enjoys, gives her access to a catalog of different fully-furnished places to live. Her last two employment contracts required proof that she was subscribed to this kind of service. Her labor is both in and on demand, so she is never sure if she’ll need to spend days, weeks, or months on site in Seoul, Los Angeles, Berlin, or Lagos. All she has to do is give two weeks’ notice and a new, fully furnished room will be waiting for her in the new city. Her AliUber subscription means that whenever she has to move, she can just cram whatever she doesn’t rent—now nothing more than her mother’s old jewelry, a favorite sweater, and a travel mug—into a vintage Herschel duffle bag and catch the next flight out of town. This time it’s to Dubai.

She still has plenty to do before decamping to the UAE. The architect gets dressed and has the usual provided breakfast in her building’s shared kitchen. Her building mates say they’ll miss her. One will be joining her in Dubai—it’s just a coincidence—next month. Others promise to use one of their five annual moving vouchers to visit. She wishes everyone well and heads down the block to Whole Foods. She remembers her parents used to use a similar subscription service to get discounted food, but now you need to be an AliUber member to afford anything in the store: paying with cash can be anywhere between ten to fifty percent more expensive. She gets snacks for the trip and they’re all debited from the food portion of her account. She makes sure everything is alright with her flight in a coffee shop that is also only for AliUber members. Turns out her flight has been moved up by an hour. She’d planned on saving some money by taking a sponsored car trip that had a mandatory stop at a new burrito chain, but flight times, like the weather, are increasingly harder to predict. She’ll have to use some of that extra spending cash to top up her allotted car trips and go straight to the airport.

After getting to the gate—her subscription level gets her into a shorter security line and an early boarding group—she reads the news. Out in the suburbs of Cleveland, longtime residents are frustrated that they can barely use their downtown without an AliUber subscription. Half the cafes, stores, and bars are for subscribers only. “I went right into my favorite diner,” laments a woman returning to her hometown to take care of her elderly father, “but they said they don’t take cash! You need AliUber credits to buy anything.” Our architect tries to remember the last time she bought something that wasn’t debited to her AliUber account. She struggles to remember the denominations of cash that still circulate in the United States, and has no clue what they are in the UAE.

The car that picks her up from the airport is driven by a man that is new to the city as well. He judiciously follows the directions on his phone and her final destination is easy to spot, thanks to the unified design language of AliUber’s residential entryways that stand out against the finely-curated vernacular architecture of the rest of the building. When she arrives in her new place, jetlagged but excited about the new city she’ll be calling home this month, she admires the regional touches to the room. In New York, her dresser had a brass model of a subway car on it. Here, it is a piece of intricately woven Bedouin tapestry framed in a shadow box. In the shared kitchen, she learns that the bagel and schmear she enjoyed every Sunday is to be replaced with couscous and dates. She feels a pang of homesickness but is quickly overpowered by a familiar love of the new.

Promotional image used on the website of Roam for its coliving and coworking space in Tokyo.

A Life Well Subscribed

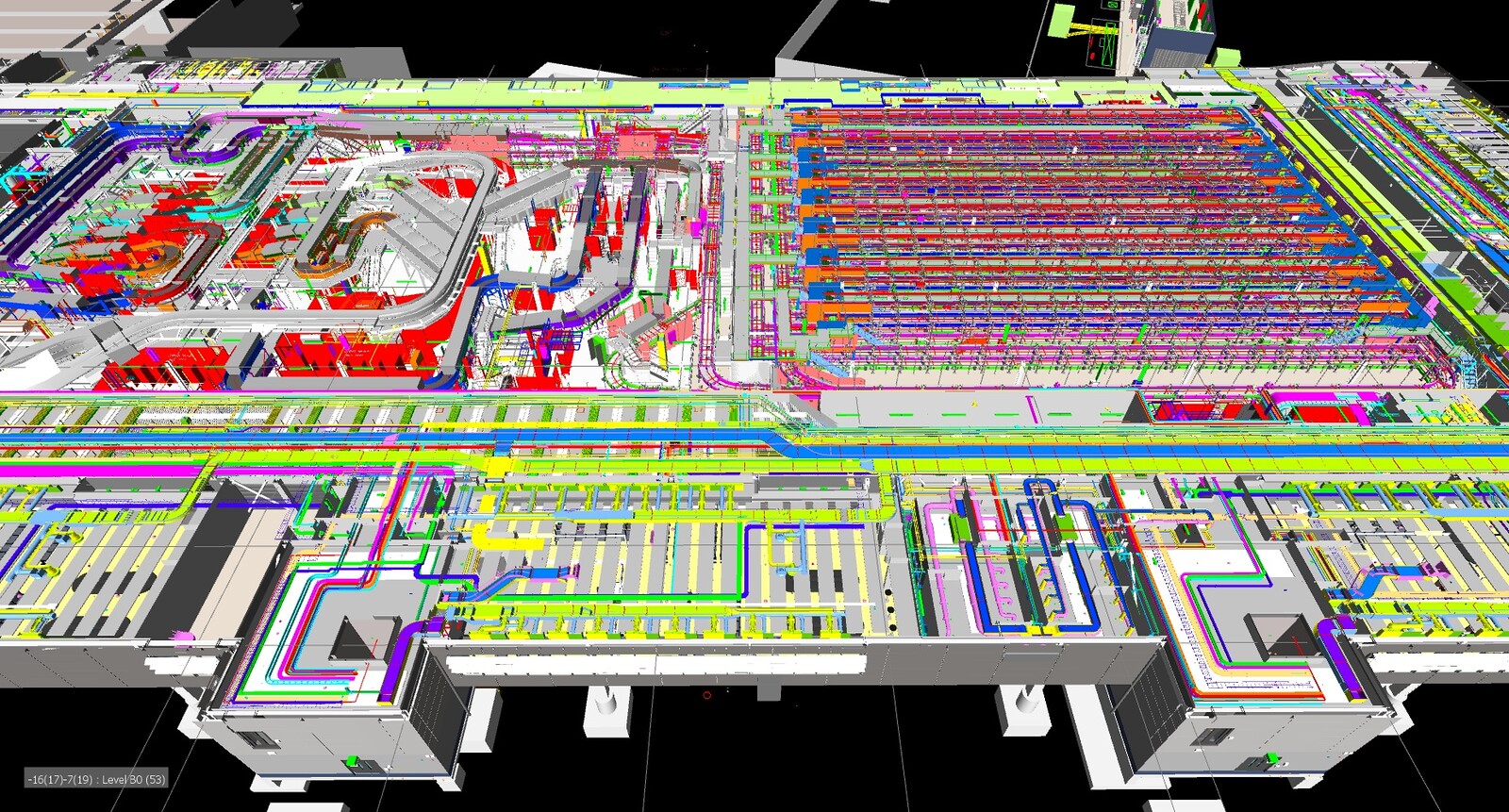

Back to reality: all of this is either already available in some limited form, or just on the horizon. Multinational companies are pivoting to subscription services for everything from make-at-home meals to video games. It may not seem like it now, but a life well-subscribed is a danger to the dignity of architecture and the places we cherish. Before their failed IPO, The We Company seemed best positioned to create a world of subscriptions. And even with their stumble, they are still a formidable force, with a portfolio of acquired companies that own patents to the necessary technology. In 2019 alone they bought companies (and their patented technologies) focused on tracking people in space, controlling and managing access to buildings, and messaging apps for campuses and organizations. In previous years, they also picked up a handful of coworking competitors including one that specialized in retail spaces. More successful companies have other parts of this system already in place: Amazon owns Whole Foods, which gives discounts to Amazon Prime subscribers, and Uber (which now offers the option to pay an annual fee for a set amount of rides) is reportedly testing the possibility of offering free rides if the customer makes a pitstop at a sponsor or makes a purchase.1

These subscription packages don’t end with organic blueberries and car rides. Markets for local culture have recently been supercharged with the rise of new digital platforms that let consumers choose different experiences tied to local culture and context. According to the journalist Kyle Chayka, “There are more tourists now than ever before,” and the character of that tourism is less of “a localized phenomenon that we encounter in crowded piazzas and then leave but an omnipresent condition, like climate change or the internet, that we inhabit all the time.”2 An even more radical shift is happening in how people chose where to live: companies are now selling access to a library of locations like Spotify sells access to their music catalog. These changes risk turning place, and the built environment that defines it, into just another commodity to be bought, sold, or subscribed to.

In addition to the obvious strictures on individuals’ privacy and right to access all parts of their city, this new wave of corporatizing urban culture will finish the job urban renewal started half a century ago. It will turn cities into malls, organized by invisible barriers made up of digital sensors attached to account databases. And if the subscription model does to architecture what Spotify has already done to music, then buildings themselves will become less valuable as the intermediary companies that manage access sop up capital by the billions.3 Of most concern to architects is that even starchitects will be expected to build cartoonish derivations of vernacular design, as place becomes just another brand.

By renting everything from a single organization like The We Company, “you might enjoy unprecedented convenience and luxury, paying for access to a network of para-state services with only a single WeNation bill. But the moment you lose your job you will be summarily kicked out, left to travel the Cursed Earth like Rob Schneider’s Fergie in Judge Dredd.”4 If our architect missed a payment, she would lose access to her shelter, food, and transportation all at once. But even if she never missed a payment, what would her life be like? What would her profession be like?

In a globalized economy, just about anything can end up anywhere. A bell pepper in Argentina can make its way to a Thai restaurant in Seattle in a matter of weeks, cheaper and fresher than their California counterparts. Through platforms like Amazon or Alibaba, consumers have a world’s bounty at their fingertips. Containerization has made the cost of shipping so low that millions of smartphones, cars, and other precisely designed, labor-intensive commodities can be assembled across entire continents before being brought together in a final assembling facility.

Globalization has the complicating effect of making local production-consumption patterns both rare and, if advertised as such, highly sought after. A leather coat made by hand or a bar of soap formed and cut down the street and scented with sage from a community garden can fetch a pretty penny—far more than similar-seeming items made using more conventional means and sold in a big-box chain store. Still, even these bespoke items can find an international market through internet platforms like Etsy or eBay and take advantage of global shipping facilities.

Promotional image used on the website of Roam for its coliving and coworking space in Bali.

Tripping the Life Authentic

Ever since the early days of capitalism, material culture has been under immense pressure to standardize into commodities.5 This has produced an interesting situation for architects and urban planners. You cannot ship a city block across an ocean. An enterprising individual can, however, make memorabilia that references a great place. A Kente cloth blanket bought in an Accra gift shop or a jar of hand-packed pickles with references to Brooklyn on the label are a means of buying a piece of a place. Souvenirs are nothing new but, as the sociologist Sharon Zukin once wrote, “We are eyewitnesses to a paradigm shift from a city of production to a city of consumption.”6 The city and its landscape generate value not from advanced industrial capacity, but from a well-curated cultural market.

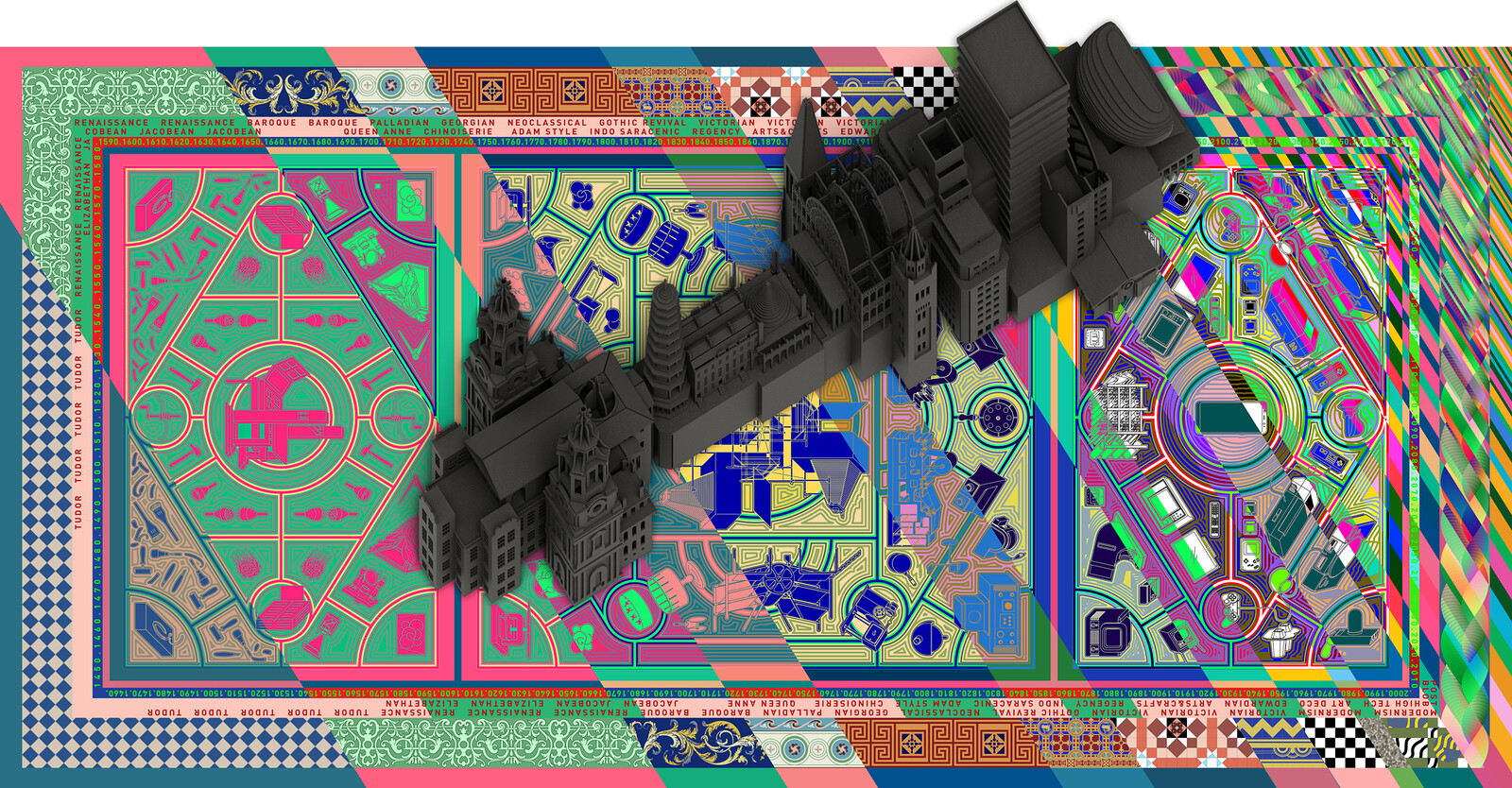

Recall the small regional changes our architect notices between New York and Dubai: the food and decorations are different, but the experience is more or less the same. The entrance to the building is identical across the world because it supports a brand identity and standardized biometric security features. The architect will increasingly find herself in a distinctly postmodern quandary, tasked with marshalling a series of increasingly dislocated symbols to signal a safe, delimited change in scenery. Picking where you live may be relegated to nothing more than choosing between different genres of Darden-owned restaurants; the choice between San Francisco and Rome will be little different than choosing between Red Lobster and Olive Garden. If the main actors in real estate and development are incentivized to provide seamless connections between places with only a few superficial cultural variations, then the patrons of architecture will seek to restore or build from scratch only those buildings that are contrivances of past cultures and places.

To be clear: art, design, and architecture have all had precarious and fraught relationships with that paradoxical and fleeting feeling we call authenticity. A hundred years ago, Walter Benjamin was lamenting the loss of art objects’ “aura” in the age of mechanical reproduction, and more recently Jean Baudrillard recognized that Disneyland’s Mainstreet USA “is presented as imaginary in order to make us believe that the rest is real, when in fact all of Los Angeles and the America surrounding it are no longer real, but of the order of the hyperreal and of simulation.”7

But as more of the global economy gets captured by industries and companies whose main function is to curate, sort, and recommend new things to consume and experience, architects and urban planners must grapple with a categorically new phase of political economy. Not just an information economy, consumer economy, or a sharing economy, but an authenticity economy. One where value is generated not just by location, or by the name of the architect, but by a place’s ability to convey a coherent brand. One that is both amenable to circuits of capital and interchangeable with any other culture—e.g. a new bauble on the dresser, a different brunch option—but also feels authentic.

Authenticity, like power or beauty, is difficult to define. It can take on an objective quality as when art historians agree on what constitutes an “authentic” Rembrandt, but most of the time authenticity is used to describe something much more ephemeral, rare, and unique: the taste of mom’s spaghetti; the patina of weathered art deco buildings in Detroit; the sound of Mongolian throat singing. Scholars disagree about what exactly it means to recognize something as authentic, but this much is clear: the feeling of authenticity lies somewhere between our expectations and the world as it is. The tourism scholar Ning Wang suggests that nearly anything can have “existential authenticity” so long as it gives someone an opportunity to engage “in non-ordinary activities, free from the constraints of the daily.”8 It is only when we lose ourselves in the moment—the music of a little-known artist no one has ever heard of, the finely preserved architectural detail in the woodwork of a small town’s Queen Anne mansion— that we feel authenticity tickle the back of our brain.

Promotional image used on the website of Roam for its coliving and coworking space in Miami.

A Game Called Monopoly Rent

Much of the value that comes out of authentic-seeming things comes down to what Marxists call “indirect monopoly rent.”9 Working backwards, rent can be used as a term to describe something that makes its owner money. The copyright to Mickey Mouse, a licensing system for software, and an apartment building generates rents for their owners. A monopoly is commonly understood to be a total capture of a market, such that the seller has inordinate control over the price. The small city that I live in has only one internet service provider, so that company can (and happily does) charge monopoly rents (read: exorbitant rates) for patchy service. Monopoly rents can be realized in as broad of terms as owning every copper mine in existence or as specific as Disney holding the intellectual property rights to Mickey Mouse. In all cases, one actor has complete control over a commodity.

The difference between direct and indirect monopoly rents is that direct monopoly rent is defined by trading something you have control over, while indirect monopoly rent is trading upon something you have control over. Think of it this way: if you were to sell a vineyard with a reputation for fine wines then you can sell it with the confidence of a direct monopoly rentier. By definition, that vineyard and its wines are incomparable to all others and thus you have no competitors. If a nearby inn chooses to advertise that they’re just one tipsy stumble away from such a vineyard, however, then they’ve found a way to collect indirect monopoly rent. In the latter case, as the geographer David Harvey argues, “it is not the land, resource, or location of unique qualities which is traded but the commodity or service produced through their use.”10 Neither the inn nor the vineyard have been traded, but the wine’s reputation provides an opportunity for the innkeeper to charge more for a room. That extra value is derived from the sense of authenticity: that the Inn provides an opportunity to step out of modern everyday life and step into something seemingly unreproducible.

Without labeling it as such, real estate agents, developers, architects, and economic development professionals know how to summon monopoly rents. Every time a neighborhood gets labeled “up and coming” or “the new Brooklyn,” it is an effort to create both direct and indirect monopoly rent prices. A successfully executed marketing campaign can turn a few blocks of run-down light industrial buildings into an up-and-coming warehouse district triggering a flurry of real estate activity. New renovations drive up the cost of remaining lots. At this point, real estate and financial firms can make money without any new construction because, according to Harvey, “Scarcity can be created by withholding the land or resource from current uses and speculating on future values.”11

At an even further remove, the flurry of real estate activity in the area conjures an ephemeral resource that sits at the center of the multi-billion-dollar tech industry: attention. Companies like Airbnb, Uber, The We Company, and Alphabet’s subsidiaries like Waymo, Waze, and Sidewalk labs cash in by offering services and managing the reputation of everyone working in the new neighborhood. Who has the best risotto? Who has the nicest car to get picked up in? Who offers the most comfortable bed to sleep in? Real estate firms and public-private partnerships promote neighborhoods through Instagram ad buys or by designing and paying to upload a custom image filter available only when a user is in the area. This leads to a cascade effect, where anyone looking to attract the attention of this new warehouse district’s business owners and potential customers are buying ads to sell ancillary services or poach customers. This attention might also attract the attention of artists who use the growing popularity of the region’s hashtag to advertise an underground music concert in one of the last remaining empty warehouses. So much the better: all of this advertising and branding sets the stage for a bevy of opportunities to collect indirect monopoly rent by both platform users and the tech companies themselves.

Promotional image used on the website of Roam for its coliving and coworking space in London.

A Network to Call Home

Tech takes advantage of indirect monopoly rent in two ways. First, companies like Airbnb act like Etsy or eBay for real estate: they take bespoke, out of the way places and connect them to international markets. The value of any given Airbnb listing is derived not just from the location and design of a space, but from the sense that you are purchasing an experience—an existentially authentic experience—and not just a mere room. The company clearly knows that this is their competitive advantage with corporate hotels, and has started offering what they call “Airbnb experiences,” where your host not only puts you up in their spare bedroom, but they’ll also cook you a dinner made from local ingredients or take you on a site-seeing tour. Instead of buying and selling a particular location (direct monopoly rent), the company is extracting rental income by charging for access to an experience that can only be conjured through interaction with an authentic-seeming place (indirect monopoly rent). In this way, Airbnb is selling its customers on a convenient, rational system designed to deliver experiences that used to only be accessible through an extensive social network of interesting people in far-away lands. Such a service is a beautiful half-truth: unlike a hotel, these places are intimate and authentic. From this vantage point you can see the “real” Rio, Austin, or Tokyo. Or, as Airbnb puts it, “We imagine a world where you can belong anywhere.”

Reserving rooms or even entire residences for the purposes of short-term rentals has the effect of raising the average cost of all rentals in an area. In London alone, Airbnb takes an estimated 50,000 housing units out of the long-term rental market.12 Another study found that Airbnb was responsible for increasing the median rent in Manhattan by more than $700 by taking between 7,000 and 13,500 properties out of the long-term rental market.13

A tight housing market creates demand for the second way tech companies make money off of indirect monopoly rents. Instead of bringing the bespoke and rare to the mainstream vacation market, tech companies put as much real estate behind a paywall as inhumanly possible. Like Spotify or Netflix, these companies rarely own much of anything and instead act as curators and middlemen between end customers and suppliers. Instead of spending thousands a month for a single bedroom in a shared apartment, new companies like Pure, Starcity, The Collective, and Common will offer what amounts to a subscription to a network of fully-furnished single occupancy rooms with on-site laundry and stocked communal kitchens for only a slightly higher price. If the gig economy takes you elsewhere—across the state or across the world—a new room will be waiting for you for a similar fee. No packing up furniture; no fighting for an apartment in an over-heated real estate market. Subscription living companies collect indirect monopoly rent by giving their customers fast and easy access to a catalogue of places in cities that are difficult to find room in. A network of well-appointed rooms in architecturally unremarkable suburbs far away from centers of employment would not command the prices that a catalogue of lofts in global cities does.

A quick survey of co-living companies’ web sites show the authenticity economy at work. Starcity promises that each of their locations, spread across the Bay Area and Los Angeles, “draw inspiration from what makes them special and incorporate these local materials, colors, and textures into all of our designs. No two neighborhoods are the same, so no two Starcity communities are the same either.”14 Kin, a co-living company geared toward families, gives subscribers “access to custom-designed shared spaces, family driven amenities, family programming, on-demand childcare, and state-of-the-art technology.”15 At one location in particular, “residents will pay a monthly fee for access to the Kin community and its family-oriented services and programming.”16

In his book Dubai: The City as Corporation, Ahmed Kanna describes the power of the city’s architecture as a means of “transnational marketing.”17 When starchitects reveal a new skyline-transforming building, they often use the same oblique, tortured references to local material culture that co-living companies use. Kanna argues that these “claims about sensitivity to local cultural and ecological worlds somehow become appended to Orientalist stereotypes.”18 In the case of American-centric co-living, they depoliticize and sanitize a local culture such that it is no more controversial or transportable than a corporate brand.

While it has been true for years that, as Kanna puts it, “downtowns have become transformed from contexts primarily for functional centrality to centers of symbolic capital” this burgeoning authenticity economy threatens to make symbolic capital the underlying operating logic for all urban living.19 For the architect, that means designing a built environment that even Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown might find difficult to divine meaning from. The profession risks becoming attendant brand managers to global landlords that see vernacular design as nothing more than literal window dressing. This is our last chance to push back against the corporatization of not just downtowns but urbanism itself, we stand to lose our cities’ cultural heritage forever.

Judith Donath, “Driverless Cars Could Make Transportation Free for Everyone—With a Catch,”The Atlantic, December 22, 2017, ➝.

Kyle Chayka, “My Own Private Iceland,” Vox, October 21, 2019, ➝.

April Glaser and Will Oremus, “The Spotify Effect,” Slate, September 6, 2018, ➝.

I have argued that this is an objectionable path to take because it will leave us less free. See David Banks, “Against We,” Commune, November 29, 2019, ➝.

Erin Besler and Ian Besler, “The Whole Architecture Catalog,” e-flux architecture, ➝.

Sharon Zukin, Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 221.

Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” trans. Harry Zohn, in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), ➝; Jean Baudrillard, “Simulacra and Simulations,” from Jean Baudrillard, Selected Writings, ed. Mark Poster (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1988), 166–184, ➝.

Ning Wang, “Rethinking Authenticity in Tourism Experience,” Annals of Tourism Research 26, no. 2 (1999): 352.

David Harvey, “The Art of Rent: Globalisation, Monopoly and the Commodification of Culture,” Socialist Register 38 (2002): 94, ➝.

Ibid., 94.

Ibid., 94.

Andy Evans and Roxane Osuna, “The Impact of Short-Term Lets: Analysing the Scale of Great Britain’s Short-Term Lets Sector and the Wider Implications for the Private Rented Sector” (London: Capital Economics, 2020) ➝.

David Wachsmuth, et al., “The High Cost of Short-Term Rentals in New York City” (New York: McGill University Urban Politics and Governance Research Group, 2018) ➝.

Starcity, ➝.

“Tishman Speyer and Common Launch Kin, First-of-Its-Kind Housing for Families,” Kin press release, March 19, 2019, ➝.

Ibid.

Ahmed Kanna, Dubai, The City as Corporation (Minneapolis: University Of Minnesota Press, 2011), 85.

Ibid., 80.

Ibid., 82.

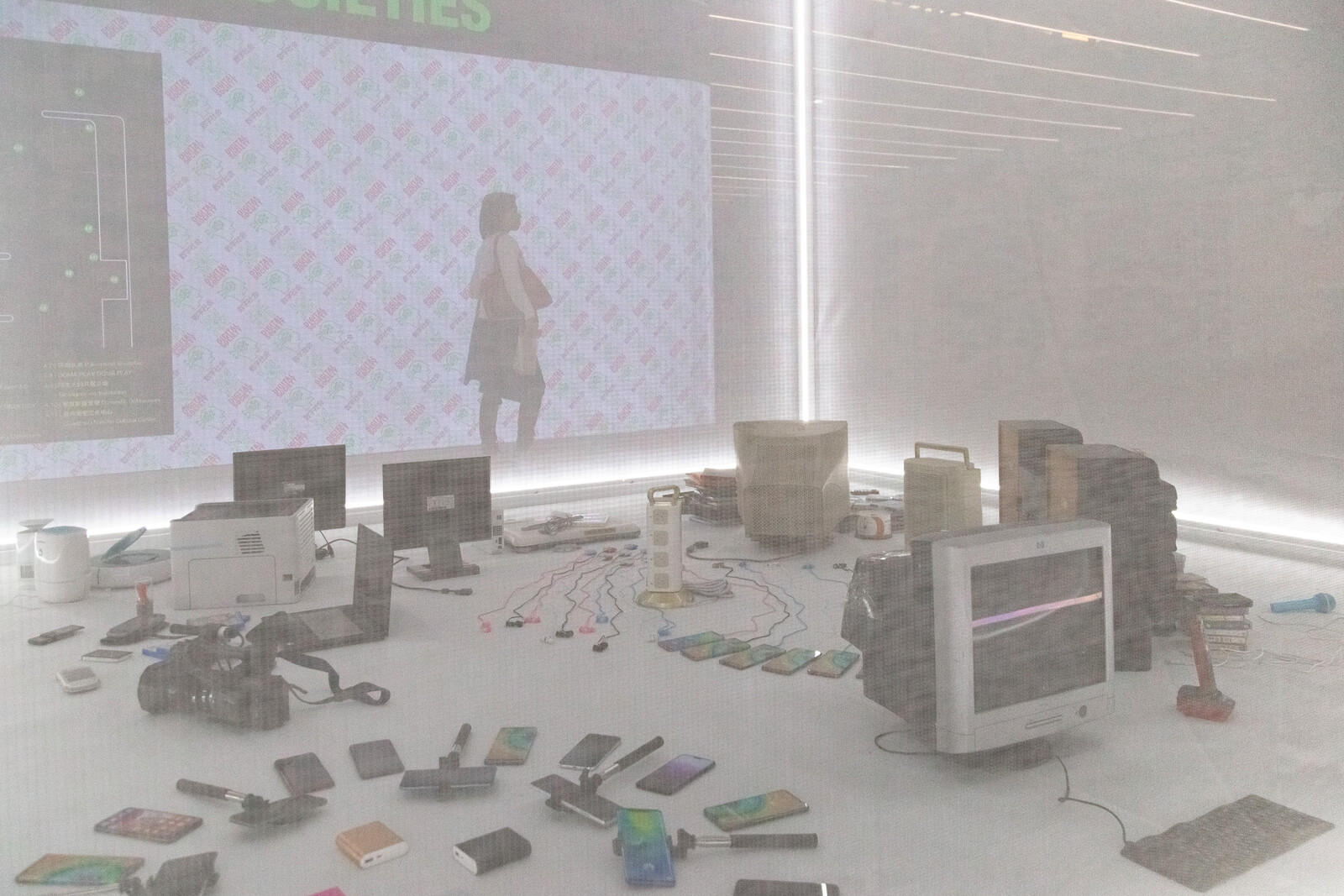

Software as Infrastructure is a project by e-flux Architecture as part of “Eyes of the City” at the 2019 Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (Shenzhen).