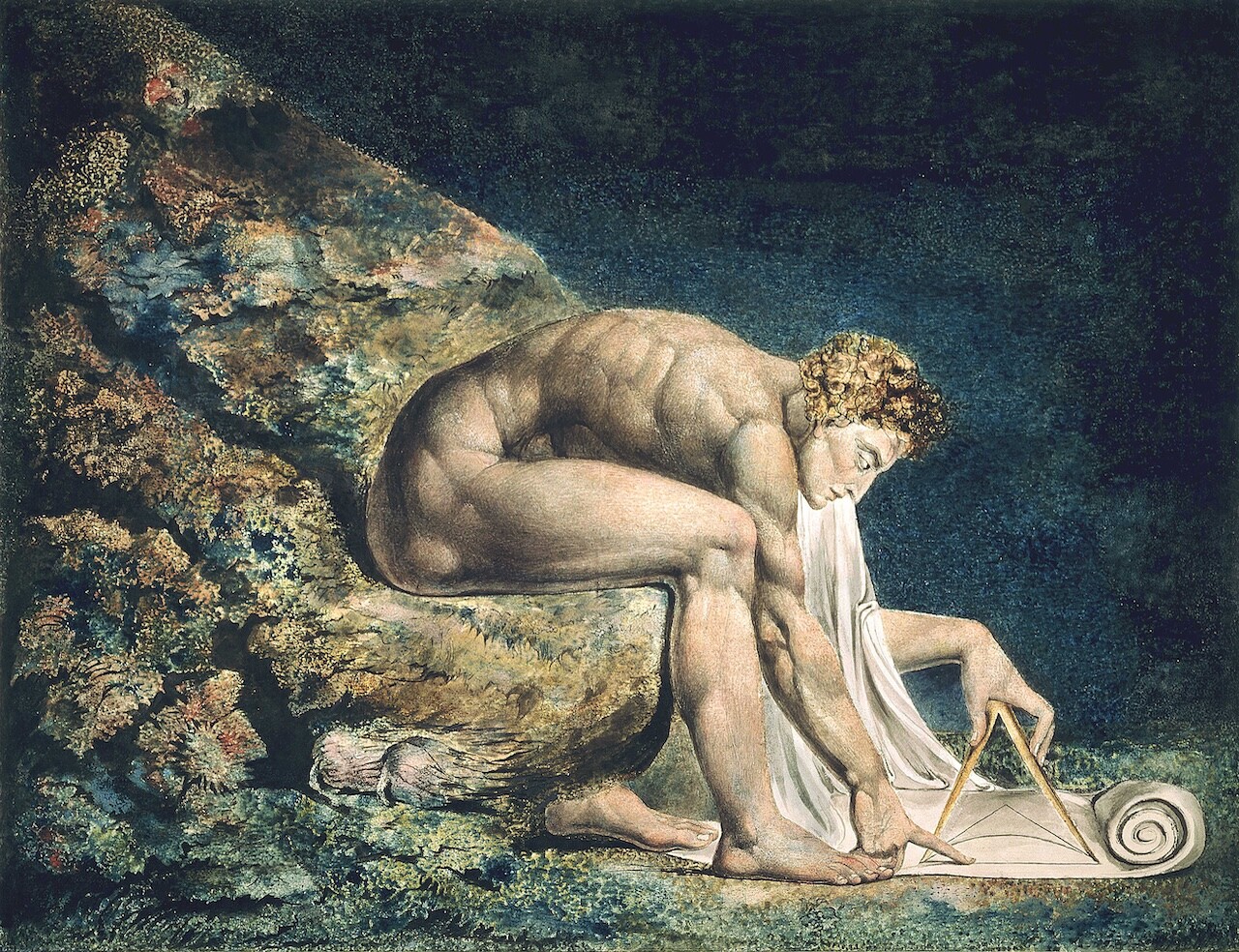

William Blake, Newton, 1795

The trigger for me to give a talk on this topic at a workshop in 2023, and then to write this short essay, and to continue thinking about the concept of facticity, came from an email exchange with a friend from my collective Chto Delat (a poet: don’t forget that poets can’t help but say something important). My friend referred to the unbearable and brutal “facticity” of the war in Ukraine at the moment of its first shock in 2022—exactly what we all felt then and now. I was also teaching a philosophy class in 2023, an introduction to Sartre’s ideas, including the concept of facticity. I was discussing “thrownness” (Heidegger’s term) or “abandonment” (Sartre) as key moods arising from becoming conscious of facticity. Personally, and to give an example—one not comparable, of course, to the horrors of the war—I myself have often felt “thrown” into the brutal facticity of my emigrant life while working in academia in the UK, with its current financial crisis, cuts, and redundancies, which are causing much stress and suffering for academics in the country.1 Some people set fire to books. Now UK academic managers are firing people who write books. This kind of brutal facticity is the result of the incredible cynicism and barbarity of turning universities into neoliberal money machines, vampirically dependent on extracting tuition fees from students, and now broken by Brexit and the post-pandemic crisis. The example also alludes to the link between facticity and late capitalism.

Since its birth in twentieth-century European philosophy (Heidegger, Sartre, Levinas, de Beauvoir, et al.), “facticity” has said something about facts, but not in a positivist sense (the truth of a fact as opposed to vague speculation, fake news, propaganda narratives, etc.). Rather, it refers to a very specific mode of being: a fact is something given, “already here,” “something that has just happened,” something contingent and blind, something to which we can hardly attach any meaning or establish the necessary and complete causal chain that led to it—a car accident, a plane crash, a war, an oil spill, or a nuclear meltdown. More broadly, the concept of facticity emerged from the collapse of philosophical idealism and its crypto-theological premises, which began already in the nineteenth century. While recognizing the laws and regularities discovered in nature by the sciences, it is no longer possible to presuppose a world spirit, or even a more modest “mole of history,” secretly working to bring together the events of the social and historical universe into a coherent whole (whether dialectical, teleological, or simply linear). The logic of the concept and of the historical positivity of “what happened” do not always converge. Already for Marx, the concept of capital is structurally similar to Hegel’s figure of Spirit or Idea, but they nonetheless diverge because capital, although it develops dialectically, eventually creates a critical discrepancy between the ideal norm and the brutal fact, between ideology (“democracy,” “human rights”) and the cruel actual state of affairs, marked by exploitation, the abuse of authority, injustice, violence, and war.2 At around the same time, Emile Durkheim introduced the notion of the “social fact,” which emphasized the transcendence of the social in relation to the individual consciousness to which it cannot be reduced. (Let us recall that in our time Fredric Jameson, in his ecumenical Marxist perspective, also insisted on this idea, reading the “social fact” in its temporal unfolding as History with a capital “H.”) The difference that constitutes a “social fact” was understood as a conceptual difference supported by empirical evidence of the transindividual coerciveness of the social, forcing us to behave in specific ways (collective representations, rites, norms, and so on). However, today this difference of the “social fact” is captured rather through the harvesting of “big data,” which has become so intensely present in the recent times of pandemics and wars (Covid cases, casualties …). This has perhaps given rise to a new kind of a “numerical facticity” that overwhelms and challenges our individual capacities to imagine and make sense of it—if this sense is understood outside of the lucrative marketing analysis and audience targeting of advertising.3

From another perspective—that is, of the individual rather than the social—there was another opening that led to the discovery of facticity. Philosophy that understood consciousness as an entity working through concepts and universals as its only proper element was confronted with an increasingly apparent discrepancy between conceptual content and the external world of the given, as if singular things and details began to resist the categorical grid that promised to reconnect the singular with the universal. One solution, revolutionary for twentieth-century philosophy, was offered by Husserl’s phenomenology, which proclaimed a return to “things themselves,” in the sense of a careful description of the intentionality of our consciousness towards them, while at the same time bracketing any concept-based assumptions about their reality. This move paved the way for a new philosophical attitude towards the stubborn givenness of things and our very existence, not subordinated to the logic of the concept. In his early lecture courses of the 1920s, Heidegger speaks of a “factical life” (“das faktische Leben”) and later introduces the term “facticity.” Our Dasein (i.e., our “being there,” in the concrete world) is not something that is preprogrammed by an individual concept or essence (as Leibniz, for example, said in the seventeenth century), but is always already “thrown” into the factical composition of contingent events, circumstances, fixities, and other accidents. Or, as Sartre would later summarize in his famous and simple line, our “existence precedes essence.”4 This precedence of existence, with all its singularity, dispersion, contingency, and brutality, also demands that we respond to our abyssal and anxious freedom from any ground, including the solid but no longer relevant precedence of the concept. In short, facticity can be strange, maddening, nauseating, and depressing.

These two faces of facticity, situated between individual and social poles, can be seen as complementary to one another, and to constitute the preconditions for a critical concept of facticity relevant today. To put it in the form of a brief sketch and a few speculative hypotheses related to the present, facticity refers to the mode of being of a fact that is characterized by:

(1) its contingent character, which is different from an abstract possibility or impossibility (the car crash might or might not happen under slightly different conditions);

(2) its initial meaninglessness that overwhelms us (and which could later and retroactively acquire far-reaching consequences and trigger an intense production of meaning, as in the case of trauma); and

(3) its blind and obsessive “givenness” (it’s just here, whether we want to see it or not).

Examples of facticity include not only extraordinary or exceptional events or “limit situations” that shock us, but also routine and long-term forms of fixity and givenness—the town and country we were born in, the name we were given at birth, our sex and gender, the race and class affiliations we were given because we were born with a socially conditioned “package” we call human life. These facts are certainly not produced by divine decision, but neither are they entirely determined by some structural necessity. This routine facticity is the contingent distribution of social and bio-morphological “facts” in relation to our conscious subjectivities. We can address them retroactively in the course of our lives by changing the place or country of our birth through emigration, by changing our gender, by building an “outstanding” career that puts us into a different class, or, in a much more radical way, by joining others in a revolutionary attempt to change the whole of society in order to abolish classes, as happens in some rather rare moments in history. Even the fact of being born into the species “Homo sapiens” (with its peculiar physical appearance, morphology, and evolutionary trajectory) presents an example of facticity, as does the very existence of our species on planet earth, which today seems to be more and more fragile and exposed to the play of cosmic and earthly contingencies such as meteorites, solar flares, and the progressive depletion of the planet’s resources.

The term “facticity” derives from the word “fact,” which in turn refers to something that is done, produced, or made. The Latin “factum” means a “thing done” and is related to the verb “facere,” “to do.” The word “fact” has gradually become established in modernity as a colloquial term, but also as an epistemic model of verification in science, and finally, as a key term in positivist ideological discourse which considers a static set of facts as the only reality given to us. Positivism excludes the critique of these facts, their possible change and transformation driven by the demands of another—possible and better—world. At the same time, the word “fact” originally had a strong negative connotation, referring to a criminal incident and the evidence (factum) of it produced during an investigation. It would not be surprising if this “criminal” subtext of facticity is related to the violence of capitalist primitive accumulation that took place in early modernity at the same time as the use of the word “fact” emerged. As the Soviet philosopher Mikhail Lifshitz subtly argued, capital itself is perfectly logical and systemic, but its very emergence is due to external facticity—so-called primitive accumulation, with all its contingencies, brutality, and violence. Since primitive accumulation is now seen not as something original that happened only once in the early modern period, but as accompanying capitalism in all its historical sequences, the generation of facticity can be seen as deeply intertwined with it.5 The philosophical uses of the term have perhaps partly retained the original meaning of “fact,” presenting it as a negative and onerous matter of circumstance, an accident devoid of meaning and premised on contingency. It is this relation to the hidden negativity of fact that creates an atmosphere of “thrownness” and “abandonment” and signifies the exposure of our bare life to imminent biopolitical capture and eco-political doom.

The period in which the concept of facticity was coined stretched from the 1920s to the 1950s, through the turmoil of the Great Depression, the rise of fascism, and two world wars and their aftermath, which threatened humanity with nuclear extinction. Today, the 24/7 machine of “communicative capitalism” (Jodi Dean) continuously produces an enormous mass of factual material and narratives that supposedly reflect the current crisis, but at the same time it creates both a growing sense of a lack of meaning (absurdity, weirdness, eeriness) and overdetermination that provokes various conspiracy theories. Another aspect of the same predicament is the proliferation of “alternative facts,” generated and disseminated through social media, which express a profound crisis of the normative or symbolic authority that would give them some degree of verification and credibility (scientific, governmental, or “professional”). The Italian thinker Paolo Virno discusses this contemporary collapse of the distinction between fact and norm as a dimension of the permanent state of exception, diagnosed by many thinkers from Schmitt and Benjamin to Agamben (and even Nietzsche, whose Genealogy of Morals traced the ideal norm back to brutal facts of the past).6 Paradoxically, facticity becomes even more symptomatic of the contemporary situation: facts may be distrusted, but the overwhelming feeling of being “thrown” into them becomes all the more intense in this predicament, and so we arrive at something that can be called “facticity without facts.”7 This kind of pure and condensed facticity as something “exotic,” weird, and uncanny also gives rise to an aesthetic that can be found, for example, in the films of David Lynch (as Mark Fisher convincingly argued in The Weird And The Eerie).8 To recapitulate: the contemporary tendency towards “facticitization” only reveals that facticity is perhaps inherent to capitalism itself, that is, to the mode of production that turns the world—with its already critically damaged but still remaining diversity of living species, including our own—into calculable, dead, and commodifiable “facts.” And isn’t Trump, who looks like a hallucinatory character from a Lynch film, an embodiment of this convergence of brutal fact and capital?

I believe that the concept of facticity is more relevant today than ever before, in the current global sociopolitical and ecological “polycrisis.” We all feel “thrown” onto planet earth, and it’s only we who can break the capitalist machine of brutal facticity and then re-function it in a different, non-destructive, and truly communized way. A child who asks, “Why is the sky blue?” may receive various answers, starting with a reference to scientific knowledge about the formation and perception of colors. However, the philosophical question here does not concern “blue” as such, but bears on the facticity of the sky being blue (in sci-fi novels and films we can see the skies in other colors). The good news from the child is that facticity is not only negative and brutal, but also suggests the possibility of a radical change of facts. This childish question reminds us that the facts can be different, and that their transformation is possible and urgent.

A different version of this text will appear in Prospective Lexicon, ed. Lara Favaretto, forthcoming in 2026.

Cuts and redundancies are currently affecting more than half of UK universities, according to the country’s main academic union. See “UK HE shrinking” →.

This argument should be distinguished from another that also comes out of the Marxist tradition (for example, out of the Frankfurt School, in particular Herbert Marcuse’s One Dimensional Man): that facticity is an effect of capitalist reification, which presents facts as things (res), that is, as something natural, objective, and thereby concealing their origins in human labor.

Incidentally, isn’t AI an attempt to turn the intelligence of our species into the brutal facticity of text- and image-generation by the likes of ChatGPT?

Of course, these brief points would require a more nuanced discussion than I can provide here, such as the difference between Sartre’s understanding (facticity as just “thrownness” into the “there” of a given contingency), and the more complex one in early Heidegger (facticity is not merely a mode of being of a brutal fact, factum brutum; rather Being itself is at issue, and is revealed in the factical “being there” of Dasein …). See Giorgio Agamben, “The Passion of Facticity,” in Potentialities: Collected Essays in Philosophy (Stanford University Press, 1999), 189.

Although an orthodox Marxist, Lifshitz made conscious and systematic use of the term “facticity,” and his late notes on Heidegger have recently been published as part of his archive. See Mikhail Lifshitz, Chto takoe klassika? (What is the classic?) ( Iskusstvo XXII Vek, 2004).

Alexei Penzin, “The Soviets of the Multitude: On Collectivity and Collective Work: An Interview with Paolo Virno,” Mediations 25, no. 1 (Fall 2010): 86 →.

Perhaps Quentin Meillassoux’s idea of “factiality,” which he presents as the “speculative essence” of facticity (that is, facticity itself is not a fact, but something that can be deduced and shown as necessary, not as contingent itself), reflects this condition of facticity without facts.

Mark Fisher, “Curtains and Holes: David Lynch,” in The Weird and the Eerie (Repeater, 2016).