When groups of lesbians started to break into and squat vacant council properties across London in the early 1970s, they had to learn how to install locks for their new homes. As working-class women and single mothers were denied access to standard social housing designed around the needs of the nuclear family, Yale barrels and copies of keys passed from hand to hand allowed them to collectively define their own conditions of access. They knocked down walls between terraced houses to enable radical experiments in collective living and shared childcare.

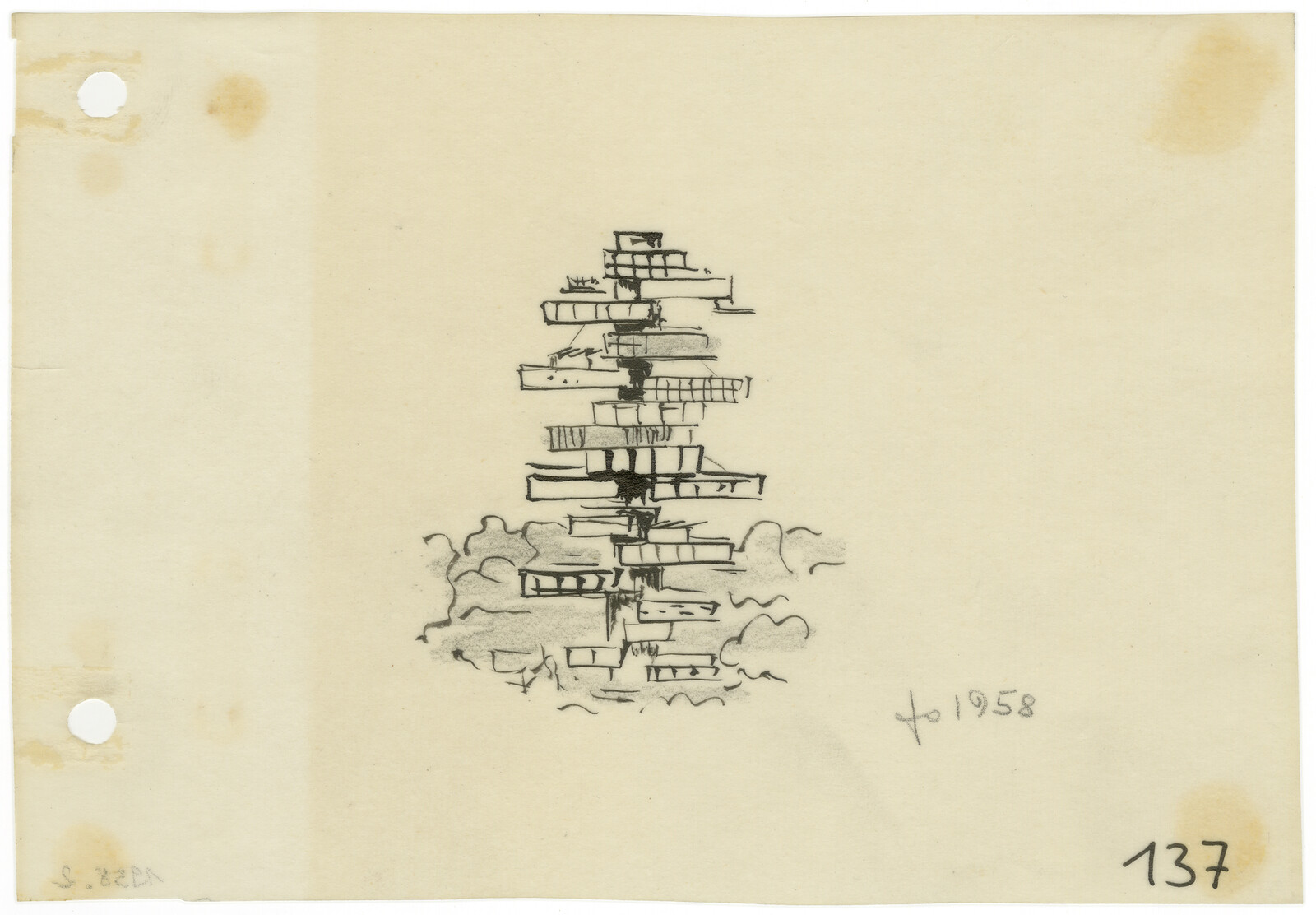

With the introduction of “Right to Buy” policy schemes and the subsequent loss of over 2.1 million council homes throughout the 1980s, squatters in London were either violently evicted or granted tenancies. But today, communal living is making a comeback, with a nexus of tech, real estate, and finance appropriating its radical history. Tube stations are filled with adverts for new “co-living” schemes with Soviet-style red-and-black graphics and slogans like “Join the Rental Rebellion.”

Co-living spaces don’t sell flats, they sell “lifestyles”—a bundling of services from housekeeping and superfast WiFi to rooftop yoga brunching, coffee machine caravans, and Sky Sports. Boosted by a £1bn government fund, they are part of the burgeoning “build-to-rent” market, largely comprised of massive purpose-built blocks of rental homes managed by a single company rather than individual landlords.1

Tipi, the “talk of the Rebellion,” currently manages 1,677 studio apartments across five buildings at Wembley Park in the London borough of Brent.2 Rent starts at £1,895 per month, and the apartments come fitted out with furniture and appliances “from our friends at John Lewis and Samsung.” Residents get access to a gym, a cinema, private lounges, and more.3 It is owned by Lone Star Funds, a global private equity firm who became a major player in the real estate debt market after the 2008 financial crash.4

All Tipi doors have “smart locks” with Bluetooth and internet of things (IoT) capabilities, and can only be opened using the MyTipi app or a PIN. This means that Tipi residents never have to go through the hassle of getting a new set of keys cut, but also that Tipi can arbitrarily exercise control over access to their apartments.

As quasi-monopolistic tech firms seek to digitally mediate all social relationships and economic transactions, property ownership is replaced by “access” to services that is always contingent.5 Cultures of access produce new forms of surveillance and social control. If the act of changing a lock embodied the squatters’ mantra that “it didn’t belong to any one of us, it belonged to all of us,” then the smart lock stands for the Silicon Valley mantra of “everything-as-a-service.”

Dirty Work

London’s squatters did not just change locks. They wielded crow bars, replaced roofs, and tapped into electric grids. When Anny Branckx, an anti-nuclear organizer who joined the women’s squatting community in Hackney, first moved into a woman-only squat on Marlborough Avenue, there was no electricity and the building had a leaking roof.6 An electrician living in another squat down the road taught them how to connect their house by laying a cable through the empty neighboring gardens, and her lover took a course in plumbing and installed a bath. Many other women went on to gain formal qualifications as plumbers and electricians. Learning these skills enabled them to intervene in their built environment, creating new spatial arrangements that facilitated communal cooking and childcare.

Dolores Hayden describes how, in recent years, feminists have come to accept the “spatial design of the isolated home, which (requires) an inordinate amount of human time and energy to sustain, as an inevitable part of domestic life.”7 But women such as Anny recognized that when reproductive activities—such as birthing and raising children, caring for friends and family, cooking, cleaning, shopping, and repairing—are shared in reciprocal relationships among an extensive group of people, it reduces costs and allows individuals to reclaim their time for work, for play, or for activism.

London’s new co-living spaces also promise to reduce burdensome reproductive labor. Tipi describes itself as “a hotel-inspired service [that] helps individuals to spend more time doing things that they really enjoy.”8 MyTipi, a dedicated tenant portal, allows residents to order a new mattress or linens, have their room cleaned, or get their laundry done at the click of a button. A concierge and resident team are always on hand, 24/7, to receive parcels, collect dry cleaning, or help with any maintenance issues. The “red-carpet renting” experience at The Collective, another co-living venture in Canary Wharf, includes access to a range of exclusive discounts and offers from delivery apps including Urban (wellness), ZipJet (laundry), Zipcar (car sharing), and Ruuby (beauty services).

In promotional material for co-living properties, there is repeated emphasis on a “frictionless” experience that is specifically enabled by digital devices. But concealed behind the slick, anonymized interface of MyTipi, friction builds as these platforms depend on a deeply classed, racialized, and gendered pool of underpaid and under-protected workers. Collectivizing activities like laundry and childcare reduces reproductive work; MyTipi merely relocates it.

Similar to how Uber’s business model exploits gaps in failing public transport infrastructure by providing its riders on-demand transit, the platform-mediated reproductive services available to residents of corporate co-living developments seek to plug holes in social infrastructure. Yet those holes only exist in the first place due to the fact that services such as care homes, community centers, and nurseries have been brutally dismantled in recent years, partly driven by the financialization of ownership linked to their value as real estate assets.9 Between these cutbacks and people working longer hours for less money, contemporary capitalism is “stretching out caring energies to breaking point.”10

Platforms like Care.com or “My Family Care” offer on-demand “back-up care” services.11 They’re solutions for when “a child is sick. A spouse has surgery. Life happens,” or simply when “care breaks down” due to the absence of a “state-sponsored safety net.”12 But the business model of these platforms, and other digital platform services enabling new co-living “lifestyles,” depends on shifting the costs of the social reproduction of the workforce onto individual workers. These companies do not pay social security contributions, sick leave, parental leave, or compensation for injury. If someone working for My Family Care has a sick kid or a broken hip, it’s unlikely they’ll be able to afford their own services.

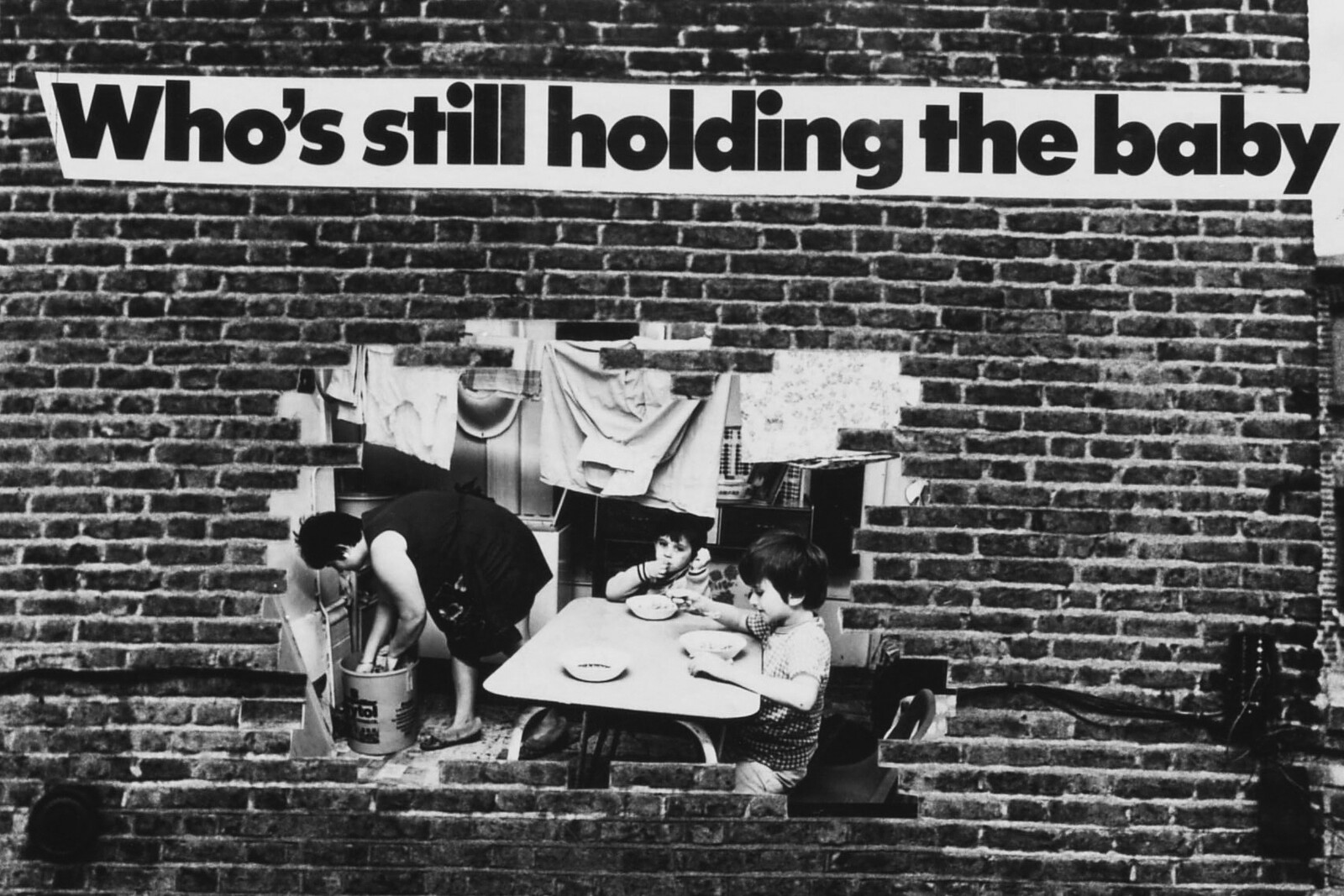

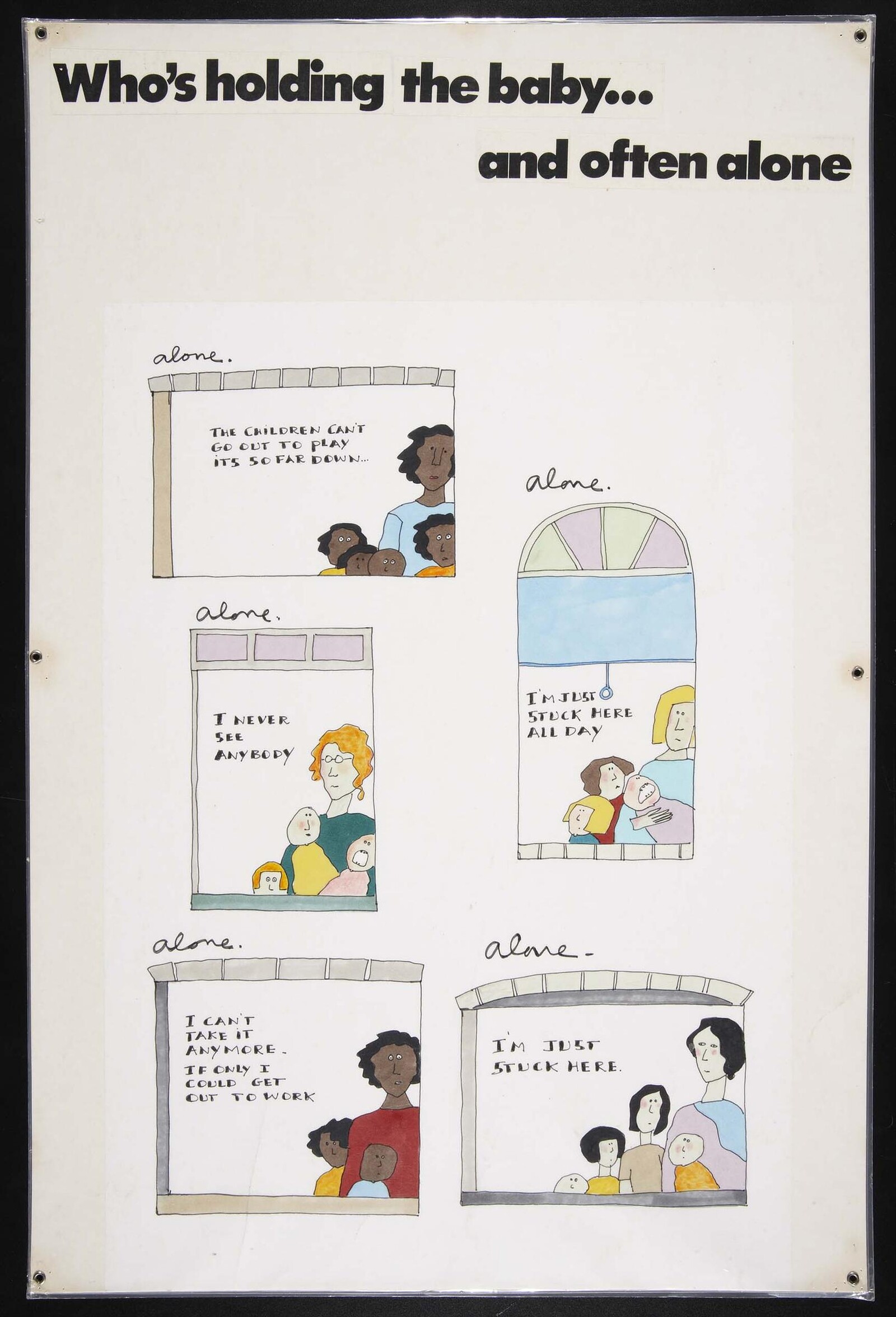

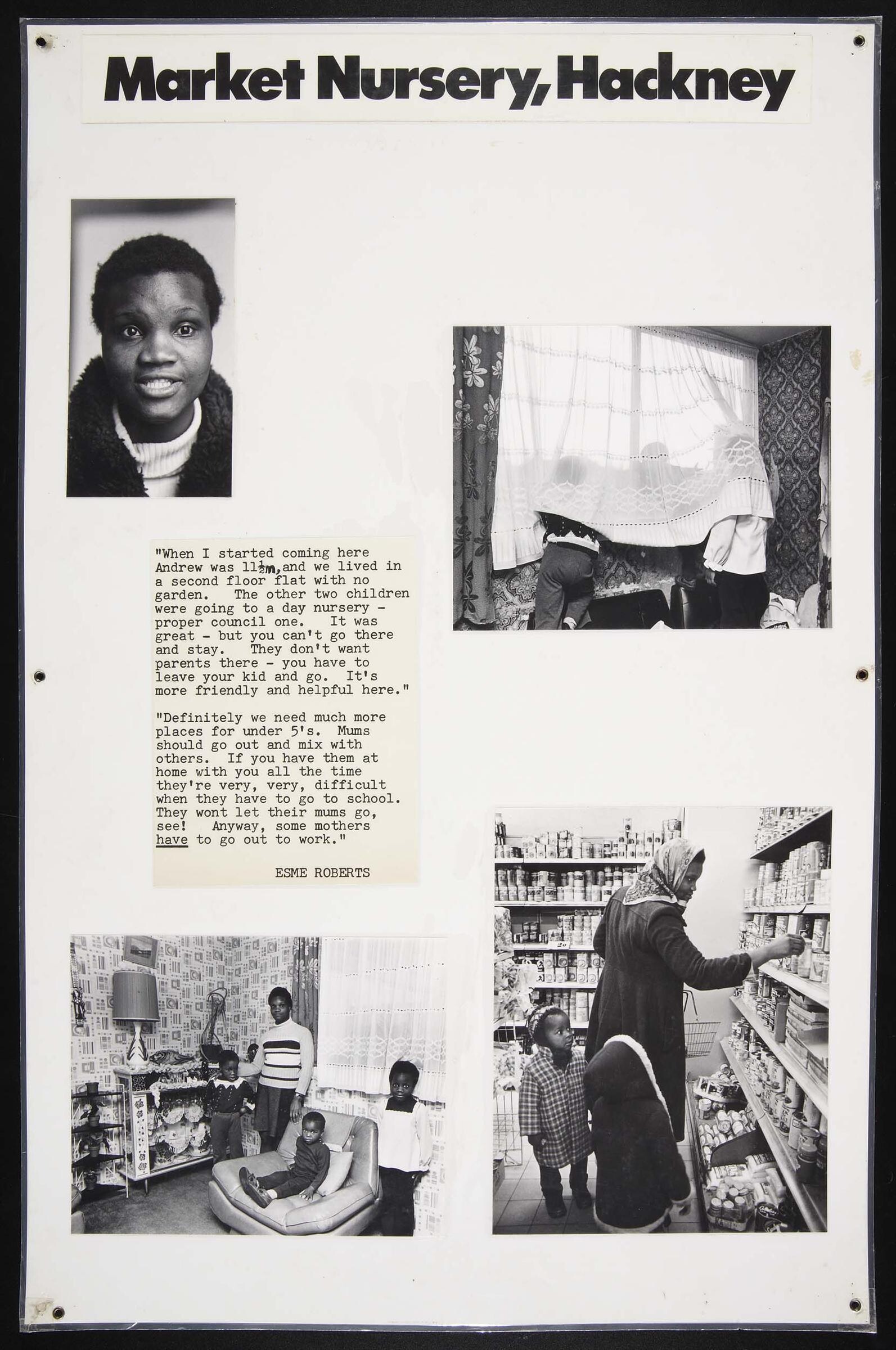

Panel 1 from Hackney Flashers, Who’s Holding the Baby?, 1980. Source: Museo Reina Sofía © Hackney Flashers.

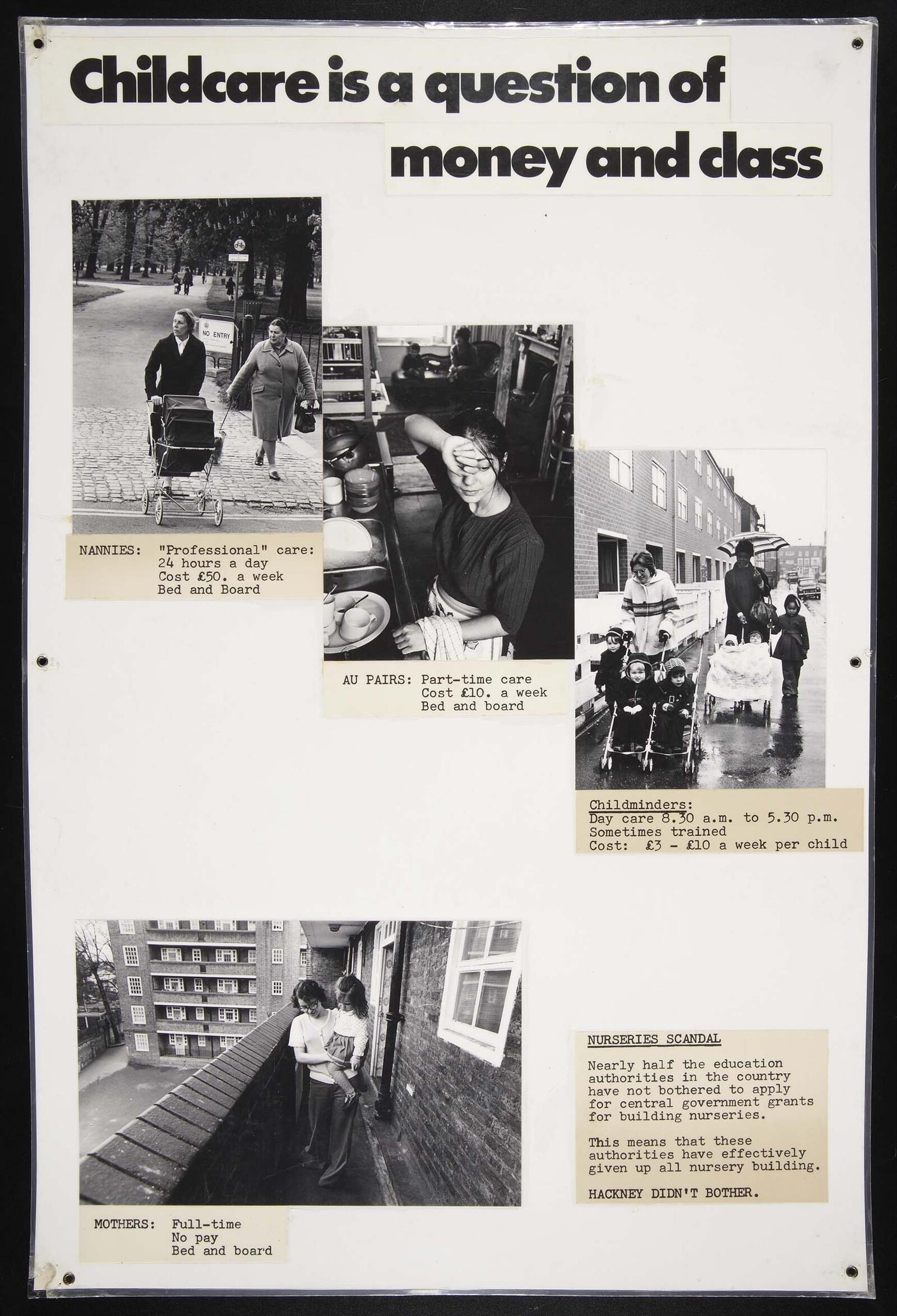

Panel 4 from Hackney Flashers, Who’s Holding the Baby?, 1980. Source: Museo Reina Sofía © Hackney Flashers.

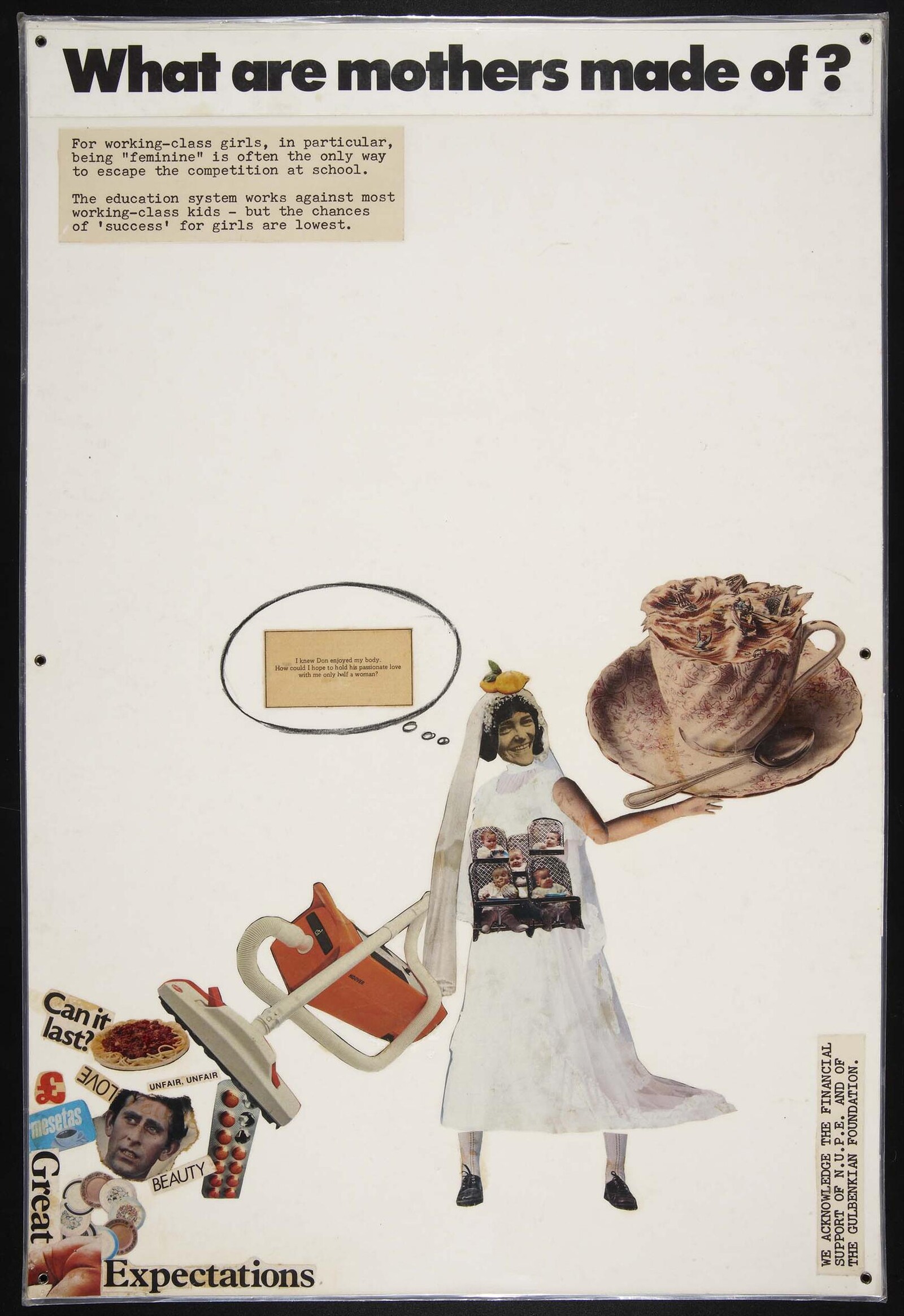

Panel 5 from Hackney Flashers, Who’s Holding the Baby?, 1980. Source: Museo Reina Sofía © Hackney Flashers.

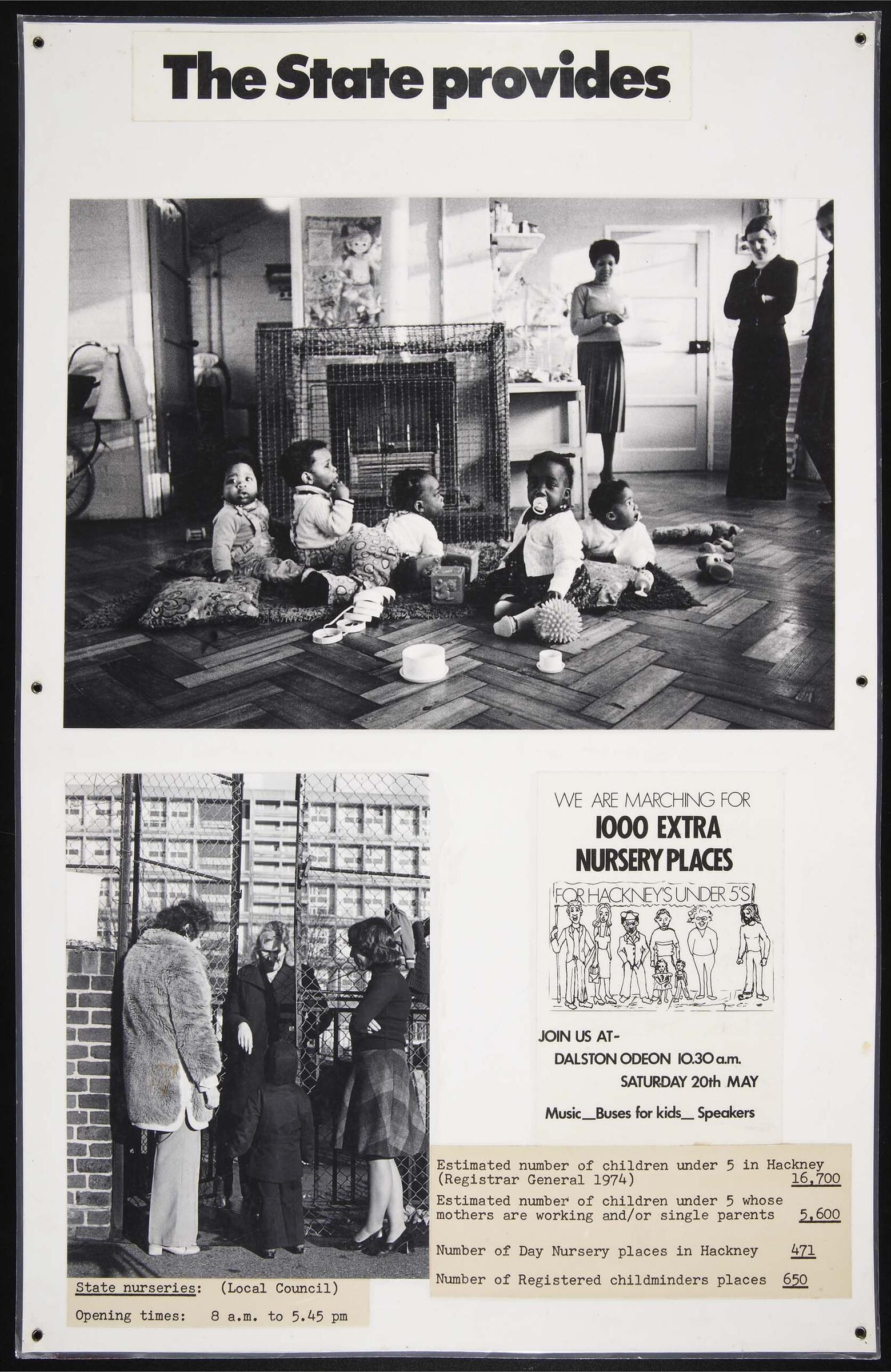

Panel 8 from Hackney Flashers, Who’s Holding the Baby?, 1980. Source: Museo Reina Sofía © Hackney Flashers.

Panel 10 from Hackney Flashers, Who’s Holding the Baby?, 1980. Source: Museo Reina Sofía © Hackney Flashers.

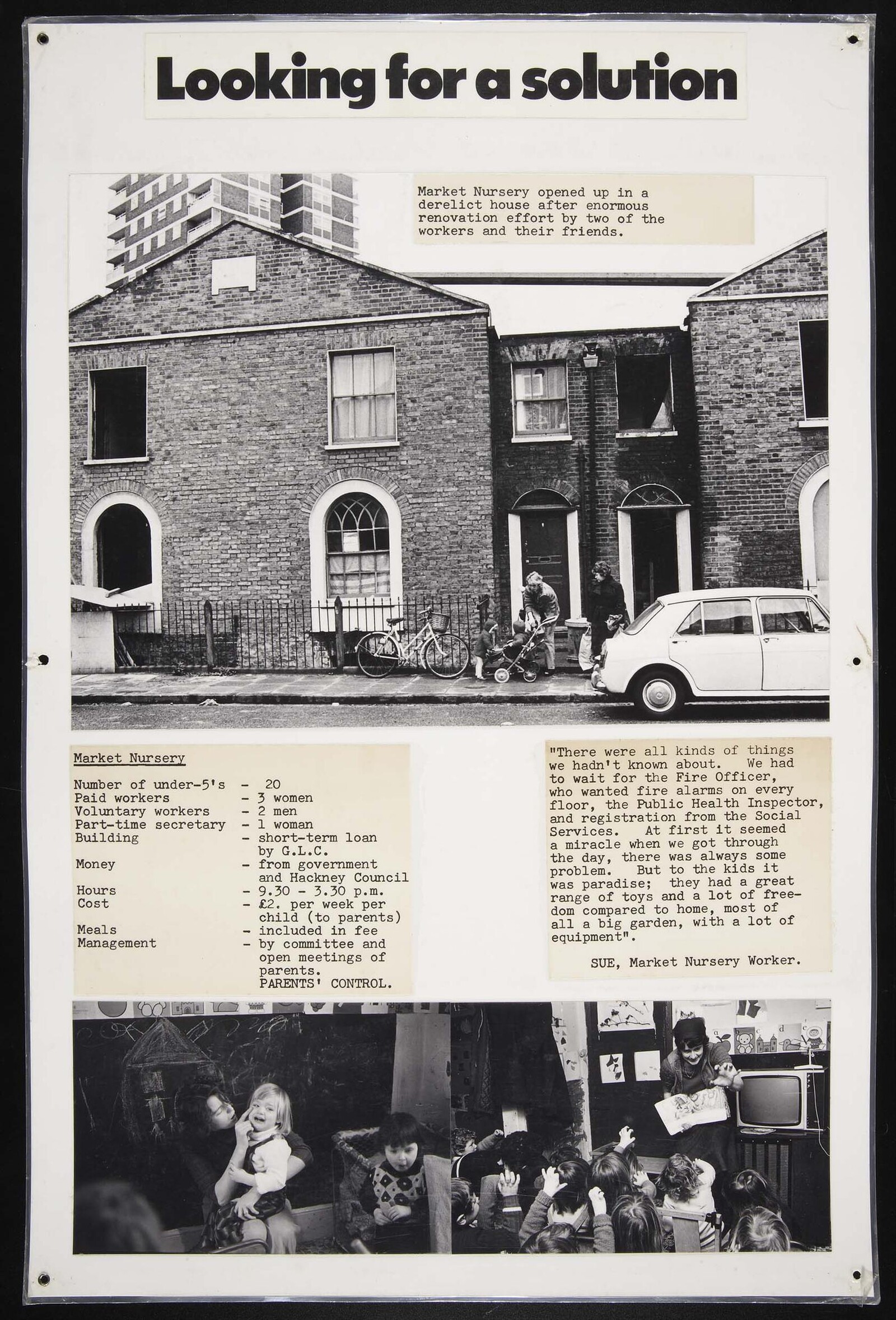

Panel 23 from Hackney Flashers, Who’s Holding the Baby?, 1980. Source: Museo Reina Sofía © Hackney Flashers.

Panel 1 from Hackney Flashers, Who’s Holding the Baby?, 1980. Source: Museo Reina Sofía © Hackney Flashers.

Robot Realtors

Algorithms don’t sweep Tipi’s floors, workers do. But digital technologies are reshaping the private rental sector in ways that demand attention. Just as platforms have accelerated the extension of intensive market dynamics into our caring relationships, new tools have enabled predatory, data-driven real estate speculation by a new class of global investor-landlords. In her account of what she calls the “automated landlord,” Desiree Fields argues that digital transformations actively participate in financial accumulation strategies, and therefore comprise a crucial terrain of struggles over housing’s place in contemporary capitalism.

Portals like MyTipi allow tenants to pay rent, get their laundry done, and request repairs using a smartphone or tablet. Combined with sensors in properties, they also generate a constant stream of property-level data that make it possible for private equity landlords like Lone Star Funds to manage massive, global portfolios of properties, automating core functions such as rent collection and maintenance and identifying inefficiencies. These portfolios of bundled incomes from tenants then act as an asset base for new financial products to be bought and sold in global capital markets.

This data stream also makes it possible for investor-landlords to monitor, measure, and manage tenants. These power dynamics are visible in recent efforts to resist the installation of smart locks. In October, 2019, residents of Knickerbocker Village in New York City, a housing development on the Lower East Side, took their landlord, Livingston Management, to court for using information collected from smart locks based on facial recognition to evict tenants.13 At the hearing, tenants argued that these tools make the predominantly migrant and ethnic minority residents feel less rather than more safe. They felt targeted by these technologies and did not receive any guarantee that the data collected wouldn’t be passed on to the police or to ICE.

Sophisticated systems are now able to fuse together and analyze datasets from different sources, including smart home devices, to create data dossiers and “scores.” These scores are then used by insurance, finance, security, as well as real estate companies to grant or deny access to products and services. Tipi recently partnered with Canopy, a company that produces an instant digital “Rent Passport,” allowing landlords to access automated background checks on their tenants. Through Canopy’s partnership with Experian, a multinational consumer credit reporting company, Tipi residents can also enhance their credit history by paying their rent directly through the mobile app.

The logic of these profiles is that you get “rewarded for reliability,” but they also punish you for being poor. The person who ends up with a bad rating because they don’t pay their rent on time is the same person who lost a week of wages because she couldn’t take jobs for a cleaning platform while her kid was off school sick.

“Log out! Log out!”

Tipi is the product of a new nexus of tech, real estate, and finance that relies on data-driven technologies to control and manage populations, from workers to renters, shaping their behavior to the demands of capital. But these transformations in real estate also unwittingly generate the necessary tools and spatial arrangements for coordinated attempts to strike back against powerful corporate actors.

Jamie Woodcock, a sociologist of work, describes how the digital outsourcing model of platforms like Deliveroo creates a double precariousness: one for workers and one for bosses—who, with virtually no human managers overseeing their workforce, have few tools at their disposal to deal with organized resistance. The UK’s first Deliveroo strike in 2016 hacked the technology designed to control workers by using promotional offers on the app to get free food delivered to the picket line, greeting fellow riders with chants of “Log out! Log out!”14 Since then, unionized couriers have organized wildcat strikes across the UK via WhatsApp in response to changes in payment structures.15

The same “double precariousness” might characterize contemporary co-living spaces as well. While the absence of available data on property ownership makes it hard to take collective action against landlords, these co-living spaces consist of thousands of renters with the same landlord who are already together in one place and able to communicate instantly via an app. Financialized, built-to-rent student accommodation in the center of London has already been the site of collective bargaining.16 In 2016, 200 UCL students withheld rent for five months, forcing the university to freeze rents and offer accommodation bursaries worth £1.4m and sparking a wave of student rent strikes across the UK.17

Data-driven technologies, increasingly used by investors to drive large-scale speculation and displacement, may also be appropriated by grassroots housing justice groups to coordinate collective resistance. The “Who Owns What” tool in New York enables community organizers to prioritize buildings for outreach,18 while the Anti Eviction Mapping Project in San Francisco has used data visualization to document dispossession.19

But too much of an emphasis on the role of digital tools for resistance can reenact the same “technological solutionism” as the Silicon Valley start-up. An understanding of the ways in which new co-living spaces and digital platforms reconfigure social reproduction in contrast with earlier experiments in radical cooperative housing is important because reproductive work sustains not just capitalism but resistance. From communal crèches and kitchens to libraries and domestic violence refuges, Marlborough Avenue provided part of the necessary physical infrastructure for feminist activism and housing campaigns in the 1970s. The 2016 UCL rent strike relied on the creation of “communities of care” with free food stalls and free parties, drawing on the example of historical rent strikes like that at the Glasgow Women’s Housing Association in 1915 and in Harlem in the 1960s. The renters’ rebellion doesn’t begin with private equity investment, it begins with care.

UK Ministry of Housing, “£3.5 billion funding boost for new rented homes,” December 11, 2014, ➝.

Tipi London, “Tipi Homes,” ➝.

Tipi London, “Living with Tipi,” ➝.

“Lone Star secures Quintain with raised deal as Elliott muscles in,” Financial Times, September 25, 2015, ➝.

Jathan Sadowski, “Landlord 2.0: Tech’s New Rentier Capitalism,” OneZero, April 4, 2019, ➝.

Quoted in Christine Wall, “Sisterhood and Squatting in the 1970s: Feminism, Housing and Urban Change in Hackney,” History Workshop Journal 83, no. 1 (Spring 2017): 79–97, ➝.

Helen Hester, “Promethean Labors and Domestic Realism,” e-flux Architecture, September 25, 2017, ➝.

Wembley Park, “Redefining renting: Tipi launches ‘The best way to live in London,’” March 30, 2016, ➝.

Amy Horton, “Financialization and non-disposable women: Real estate, debt and labour in UK care homes,” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 54, no. 1 (February 2022): 144-159.

Sarah Leonard and Nancy Fraser, “Capitalism’s Crisis of Care,” Dissent (Fall 2016), ➝.

Care@Work, ➝.

My Family Care, “2018: Three Critical HR Issues You Can’t Ignore,” January 10, 2018, ➝.

Jack Shenker, “Strike 2.0: how gig economy workers are using tech to fight back,” The Guardian, August 31, 2019, ➝.

Jamie Woodcock and Callum Cant, “The end of the beginning,” Notes From Below, June 8, 2019, ➝. Nils Van Doorn and Julia Ticona have observed that female workers on reproductive platforms are still conspicuously absent from these spaces of labor organizing.

Overseas capital accounts for 90% of investment in student accommodation. Joe Beswick et al., “Speculating on London’s Housing Future: The rise of global corporate landlords in ‘post-crisis’ urban landscapes,” City 20, no. 2 (2016): 321–341, ➝.

Alfie Packham, “Students win £1.5m pledge from UCL after five-month rent strike,” The Guardian, July 6, 2017, ➝.

Who Owns What in NYC? ➝.

Anti-Eviction Map, ➝.

Housing is a collaboration between e-flux architecture and the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology Chair for Theory of Architecture.