Ilya and Emilia Kabakov’s artistic proposals are not only inspiring but also very appropriate for our present times. It is hard to define the reason without sounding vague, because it is a sort of atmosphere, a suspension from the everyday world through the introduction of a parallel sphere that, if slightly different and not totally known, is capable of proposing sharp comments about the Real. Some of their works propose metaphors and parodies through a powerful allusive apparatus. They have a knack for generating "spaces within spaces," a knack for creating empathy with the present. By stepping into a parallel realm, indeed, evasive of reality, the viewer is equipped and ready for a change in attitude, made possible through the Kabakovs’ continuous reflections about the relations between the individuals and the collectivity established by projections and desires; it is exactly this tension between evasion and acuteness that plays a fundamental role in our current relation to the everyday.

If we consider our present times of social, economic, and political uncertainty, and the major actions that have been shaking the world around us, from the upheavals at Tahrir to the waves of indignados ebbing and flowing into the squares and streets of so many cities; to the riots that violently question the welfare states, and to the current dramas played out in Homs, it remains without a doubt that we are attempting to install new forms of relations between individuals and the structures of power that govern the world. It thus could be that the subtle, yet powerful, mature proposals of the Kabakovs could offer one of the most solid contributions from art to the general state of affairs: by placing a political awareness on the threshold between the background and the visible.

That said, and given the wide exhibiting experience of the artists, it is bizarre that the couple’s latest project in the vast spaces of the Lia Rumma Gallery is so confused and unresolved. It is not a show without its high moments though, and indeed there are some remarkable pieces. But the concept seems to be lacking, resulting in a mere agglomeration of isolated artworks.

A huge, thick, grey blanket covers almost the entire floor of the large front room of the gallery; there’s a noticeable lump, a hidden creature lurking underneath that shows no intention of trying to find a way out. Someone is Crawling under the Carpet (1998) is definitely the best moment of the show, as it welcomes the viewer into a space alluding to a puerile strategy of evasion that has turned into a grownups possibility.

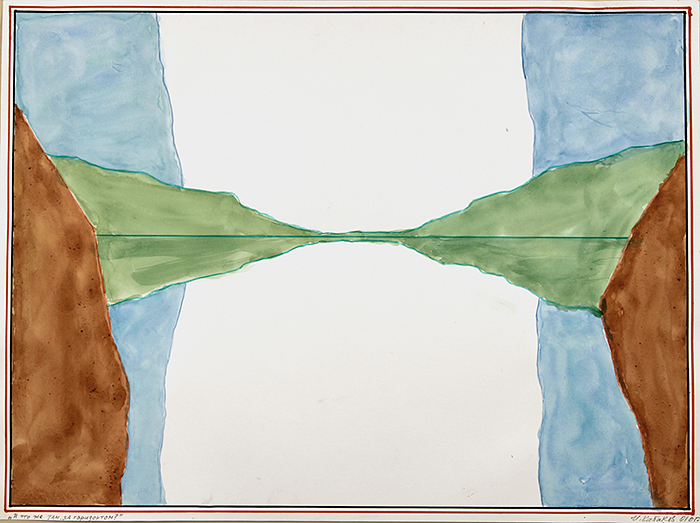

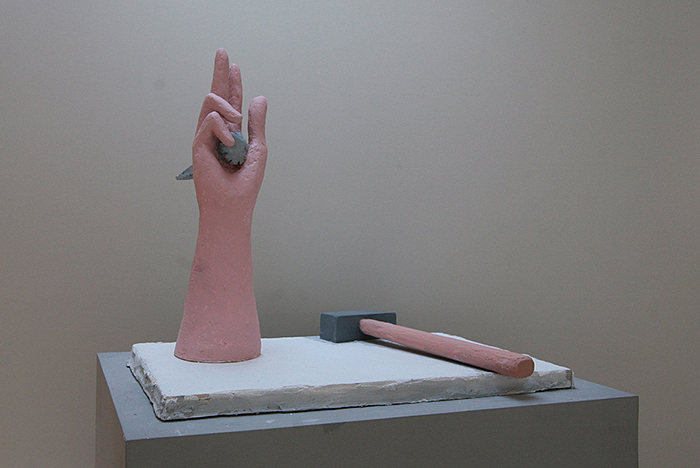

The first floor presents a sort of intermezzo, an intermission with a straightforward commercial vocation between the two main installation pieces. There one finds a great number of objects and four large paintings of the series In the Studio of Totti Kvirini (#1–4, 2009); along with four different crayon drawings done between 1997 and 2011, and five small sculptural works that launch reflections about artistic activities as such. The drawings, such as Artist! Why didn’t you paint my backside? (2011) and What is there, beyond the horizon? (2010), reference the necessary decisions of the artist; the sculptural works resemble small models for the preparation of large-scale installations (as in the ceramics Pianist and Musa and Toilet on the Mountain, both 2000, and in the small-scale maquette The Shining Circus and its Spectators, undated), while the paintings are humorist depictions of the studio of an imaginary artist, Totti Kvirini, that quite literally reflect on the genealogy of representation in painting.

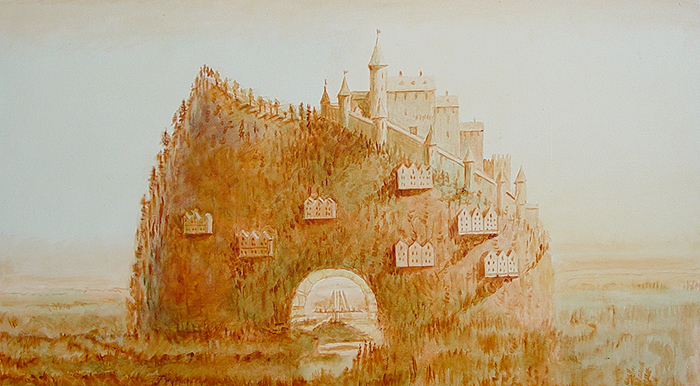

The ascension to the second floor of the gallery is not only physical but mostly spiritual. There, a large model of a magical world, Morning, Evening, and Night (2005), with its shimmering, warm light, and its soft, carillon-like melody creates an unreal, fabled atmosphere where the relation to time is so efficiently suspended that it feels like Christmas has spilled over into mid-January.

This condition of atemporality, also evidenced in the installation on the ground floor, is perhaps the most compelling element of the whole exhibition. It is simply a shame that it feels so out of time, behind the times, even, when what we need most is a relation to our present moment.