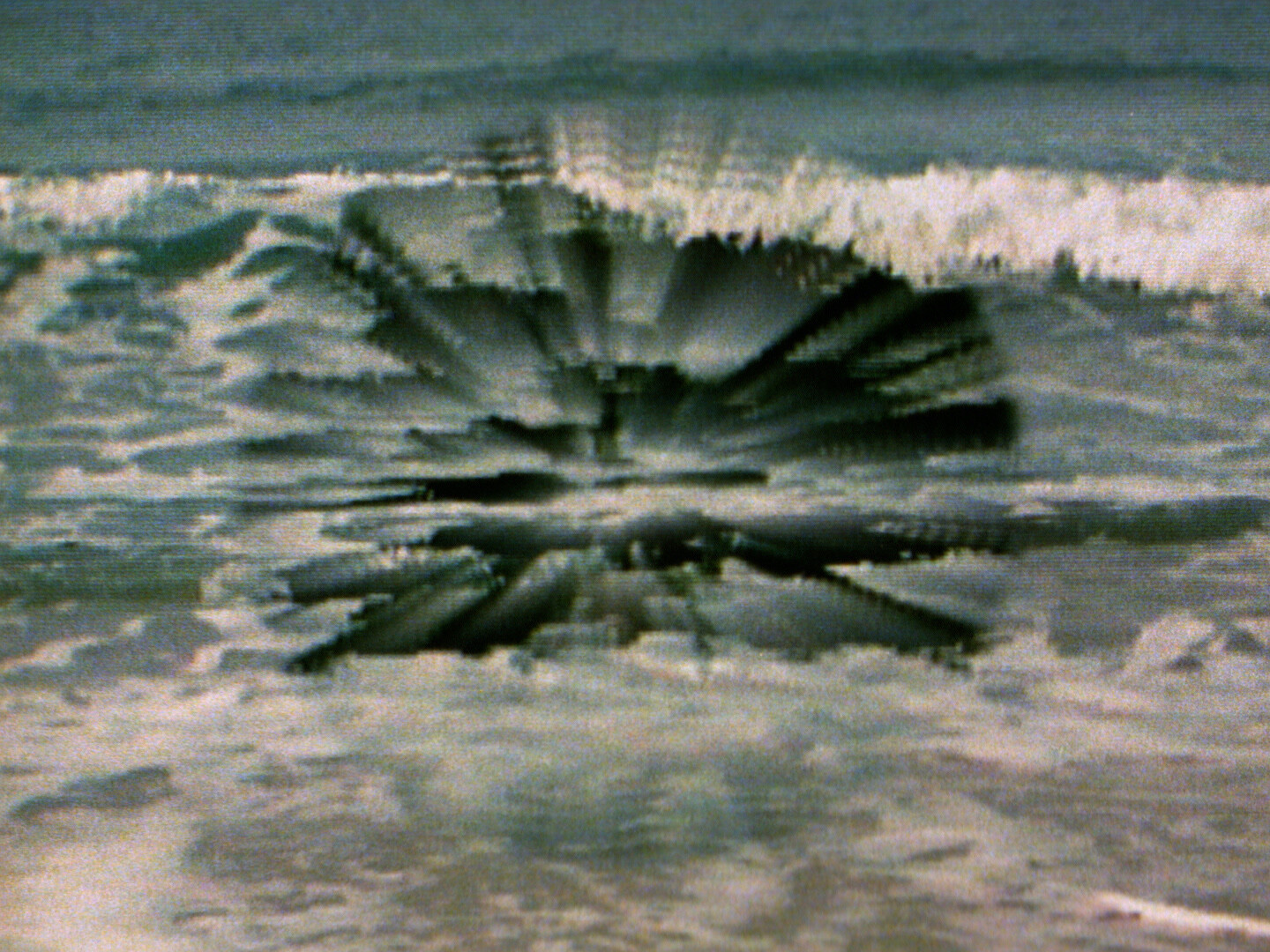

Unlike the Muybridge images, which assert control, surveillance, and dominance over Modoc territories, Piron portrays the landscape as unattainable, allowing it to tell its own story of resistance. His filmmaking process becomes forensic research: it challenges the historical misinformation in the photographs through geographical evidence. Following the rise of fake news, contemporary cinema has seen a shift towards forensics—see the works of Forensic Architecture, Larissa Sansour, the New Red Order and, even earlier, Walid Raad. These projects interrogate images and historical narratives to visualize human rights abuses and claim justice.

The show is surprisingly simple, with four works across four rooms: alongside The Hearth is The Wheel (a chandelier-like structure surrounded by music stands holding songbooks); The Oratory (where visitors are encouraged to sing into a microphone, triggering an AI model to harmonize in response, in front of another altar-like object); and, reverberating around the edges of the gallery space, a series of ethereal musical compositions called “Linked Diffusion.”

The deep boom of a subwoofer meets you on the stairs to the small gallery. Inside, a two-channel video projected across opposite walls shows barren landscapes with figures moving through them, close-ups of plants and foliage, and more besides, the imagery by turns sped up, slowed down, color-adjusted, and layered. One half is framed to the dimensions of the space; the second is projected at an angle, so the pictures invade the ceiling and floor. It is a hypnotic, unnerving assemblage.

They appear to have been lightly traced, the outlines of people, suitcases, and carts clear but not firmly insistent, the shading sometimes more so, events thrown into stark relief under an unforgiving sun. Below these “unshowable photographs,” and held also in window mounts, she added her own rather more interrogative captions, which ask questions of what is shown and not shown, and which the “truth” of the archive omit wholly.

Marx wants the reader to feel the full brutality of what capitalism does to laboring bodies. He wants to reveal the horror beneath the social codes by which the bourgeois protect themselves from the gory facts of the capitalist mode of production sustaining their existence. The bourgeois family home is built upon the jellied gore of the slaughterhouse. Marx wants to force the reader to look.

There is no trace of irony evident in the careful spatial doubling of the meditation room; the effect is remarkably peaceful. It appears to pay sincere homage to Hammarskjöld’s ambition: “There is an ancient saying that the sense of a vessel is not its shell but the void. So it is with this room. It is for those who come here to fill that void with what they find in their center of stillness.” Yet it is not true that the room is empty. In fact, it is full of competing symbols.