The Journey of a Modern Hero, to the Island of Elba. May 1814. Collection: Library of Congress.

Where does Trump’s victory leave (whatever remains of) the left? In 1922, when the Bolsheviks had to retreat into the “New Economic Policy” of allowing a much greater degree of market economy and private property, Lenin wrote a short text called “On Ascending a High Mountain.” He describes a climber who has to retreat back to the zero point, to the ground, after his first attempt to reach a new mountain peak. Lenin uses this climber as a metaphor for how one retreats without opportunistically betraying one’s fidelity to the Cause: communists “who do not give way to despondency, and who preserve their strength and flexibility ‘to begin from the beginning’ over and over again in approaching an extremely difficult task, are not doomed.”1 This is Lenin at his Beckettian best, echoing the line from Worstward Ho: “Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” And such a Leninist approach is needed now more than ever, when communism is needed more than ever as the only way to confront the challenges we face (ecology, war, AI …), even as (whatever remains of) the left is less and less able to mobilize people around a viable alternative. With Trump’s victory, the left has reached its zero point.

Before we plunge into the platitudes about “Trump’s triumph,” we should note some important details. First among them is the fact that Trump did not get more votes this time than in the 2020 election, where he lost against Biden; it was Kamala who lost around ten million votes compared to Biden! So it’s not that “Trump won big”; it’s Kamala who lost, and all leftist critics of Trump should begin with radical self-criticism. Among the points to be noted, there is the unpleasant fact that immigrants, especially from Latin American countries, are almost inherently conservative: they come to the US not to change it but to succeed in the system, or, as Todd McGowan put it: “They want to create a better life for themselves and their family, not to better their social order.“2

This is why I don’t think Kamala lost because she is a nonwhite woman. Remember that two weeks ago Kemi Badenoch, a Black woman, was triumphantly elected as the new leader of the British Conservatives. I see the main reason for Kamala’s defeat in the fact that Trump stood for politics—he (and his followers) acted as engaged politicians—while Kamala stood for non-politics. Many of Kamala’s positions were quite acceptable: healthcare, abortion … However, Trump and his partisans repeatedly made clear “extreme” statements while Kamala exceeded in avoiding difficult choices, offering empty platitudes. In this respect Kamala is close to Keir Starmer in the UK. Just recall how he avoided a clear stance on the Gaza war, losing the votes not only of radical Zionists but also of many young Black and Muslim voters.

What Democrats failed to learn from Trumpians is that, in a passionate political battle, “extremism” works. In her concession speech, Kamala said: “To the young people who are watching, it is okay to feel sad and disappointed, but please know it’s going to be okay.” No, everything is not going to be okay, we should not trust future history that it will somehow restore balance. With Trump’s victory, the trend which brought close to power the new populist right in many European countries reached its climax.

Kamala was described by Trump as worse than Biden, not just a socialist but even a communist. To confuse her stance with communism is a sad index of where we are today—a confusion clearly discernible in another oft-heard populist claim: “The people are tired of far-left rule.” An absurdity if there ever was one. New populists designate the (still) hegemonic liberal order as “far left.” No, this order is not far left, it is simply the progressive-liberal center, which is much more interested in fighting (whatever remains of) the left than the new right. If what we have now in the West is “far-left rule,” then Ursula von der Leyen is a Marxist communist (as Viktor Orban effectively claims)!

The new populist right treats communism and corporate capitalism as the same. But the true identity of opposites resides elsewhere. Eight or so years ago I was criticized for saying that Trump is a pure liberal—how could I ignore that Trump is a dictatorial fascist? My critics missed the point: perhaps the best characterization of Trump is that he is liberal, namely a liberal fascist, the ultimate proof that liberalism and fascism work together, that they are two sides of the same coin. Trump is not just authoritarian; his dream is also to allow the market to function freely at its most destructive, from brutal profiteering to dismissing all ethical limitations on the media (against sexism and racism, for example) as a form of socialism.

Here again we should begin with a critique of Trump’s opponents. Boris Buden rejected the predominant interpretation which sees the rise of the new rightist populism as a regression caused by the failure of modernization. For Buden, religion as a political force is an effect of the post-political disintegration of society, of the dissolution of traditional mechanisms that guaranteed stable communal links: fundamentalist religion is not only political, it is politics itself, i.e., it sustains the space for politics. Even more poignantly, it is no longer just a social phenomenon but the very texture of society, so that in a way society itself becomes a religious phenomenon. It is thus no longer possible to distinguish the purely spiritual aspect of religion from its politicization: in a post-political universe, religion is the predominant space in which antagonistic passions return. What happened recently in the guise of religious fundamentalism is thus not the return of religion in politics but simply the return of the political as such. So the true question is: Why did the political in the radical secular sense, the great achievement of European modernity, lose its formative power?

David Goldman commented on the election result by saying, “It’s the economy, stupid!”—but, as he added, not in a direct way. The main indicators show that under Biden the economy was doing rather well, although inflation hit the majority of poor people hard. The trend towards a larger gap between rich and poor has been a global tendency in the West for the last thirty years. Yes, higher prices for everyday products (especially food), higher rents, and higher medical costs pushed millions towards poverty, but Biden was, in his economic policies, definitely the most leftist president since Franklin D. Roosevelt, who did a lot for the rights of workers, women, and students. Inflation is thus not enough to explain the mystery: Why did a considerable majority perceive their economic predicament as dire? Here, ideology enters the picture.

We are not talking here just about ideology in the sense of ideas and guiding principles, but ideology in a more basic sense of how political discourse functions as a social link. Aaron Schuster observed that Trump is “an overpresent leader whose authority is based on his own will and who openly disdains knowledge—it is this rebellious, anti-systemic theater that serves as the point of identification for the people.”3 This is why Trump’s serial insults and outright lies, not to mention the fact that he is a convicted criminal, work for him. Trump’s ideological triumph resides in the fact that his followers experience their obedience to him as a form of subversive resistance, or, as Todd McGowan put it: “One can support the fledgling fascist leader in an attitude of total obedience while feeling oneself to be utterly radical, which is a position designed to maximize the enjoyment factor almost de facto.”4

Here we should mobilize the Freudian notion of the “theft of enjoyment”: an Other’s enjoyment that is inaccessible to us (woman’s enjoyment for men, another ethnic group’s enjoyment for our group …), or our rightful enjoyment stolen from us by an Other or threatened by an Other. Russell Sbriglia noticed how this dimension of the “theft of enjoyment” played a crucial role when Trump’s supporters stormed the Capitol on January 6, 2021:

Could there possibly be a better exemplification of the logic of the “theft of enjoyment” than the mantra that Trump supporters were chanting while storming the Capitol: “Stop the steal!”? The hedonistic, carnivalesque nature of the storming of the Capitol to “stop the steal” wasn’t merely incidental to the attempted insurrection; insofar as it was all about taking back the enjoyment (supposedly) stolen from them by the nation’s others (i.e., Blacks, Mexicans, Muslims, LGBTQ+, etc.), the element of carnival was absolutely essential to it.5

What happened on January 6, 2021 in the Capitol was not a coup attempt but a carnival. The idea that a carnival can serve as a model for progressive protest movements—such protests are carnivalesque not only in their form and atmosphere (theatrical performances, humorous chants), but also in their non-centralized organization—is deeply problematic: Is late-capitalist social reality itself not already carnivalesque? Was the infamous Kristallnacht in 1938—this half-organized, half-spontaneous outburst of violent attacks on Jewish homes, synagogues, businesses, and people themselves—not a carnival if there ever was one? Furthermore, is “carnival” not also the name for the obscene underside of power, from gang rapes to mass lynchings? Let us not forget that Mikhail Bakhtin developed the notion of carnival in his book on Rabelais written in the 1930s as a direct reply to the carnival of the Stalinist purges.

The contrast between Trump’s official ideological message (conservative values) and the style of his public performance (saying more or less whatever pops into his head, insulting others and violating all the rules of good manners …) tells a lot about our predicament: What world do we live in, in which bombarding the public with indecent vulgarities presents itself as the last step towards the triumph of a society in which everything is permitted and old values go down the drain? As Alenka Zupančič put it, Trump is not a relic of old moral-majority conservativism; he is to a much greater degree the caricatural inverted image of postmodern “permissive society” itself, a product of this society’s own antagonisms and inner limitations. Adrian Johnston proposed “a complementary twist on Jacques Lacan’s dictum according to which ‘repression is always the return of the repressed’: the return of the repressed sometimes is the most effective repression.”6 Is this not also a concise definition of the figure of Trump? As Freud said, in perversion everything that was repressed, all repressed content, comes out in all its obscenity, but this return of the repressed only strengthens the repression—and this is also why there is nothing liberating in Trump’s obscenities. They merely strengthen social oppression and mystification. Trump’s obscene performances thus express the falsity of his populism: to put it with brutal simplicity, while acting as if he cares for ordinary people he promotes big capital.

How to account for the strange fact that Donald Trump, a lewd and destitute person, the very opposite of Christian decency, can function as the chosen hero of Christian conservatives? The explanation one usually hears is that, while Christian conservatives are well aware of Trump’s problematic personality, they have chosen to ignore this side of things, since what really matters to them is Trump’s agenda, especially his antiabortion stance. If he succeeds in appointing new conservative justices to the Supreme Court, which will then overturn Roe vs. Wade, then this act will obliterate all his sins … But are things as simple as that? What if the very duality of Trump’s personality—his high moral stance accompanied by personal lewdness and vulgarity—is what make him attractive to Christian conservatives? What if they secretly identify with this very duality? This, however, doesn’t mean that we should take too seriously the images that abound in our media of a typical Trumpian as an obscene fanatic. No, the large majority of Trump voters are everyday people who appear decent and talk in a normal, calm, and rational way. It is as if they externalize their madness and obscenity in Trump.

A couple of years ago, Trump was unflatteringly compared to a man who noisily defecates in the corner of a room in which a high-class drinking party is going on—but it is easy to see that the same holds for many leading politicians around the globe. Was Erdoğan not defecating in public when, in a paranoiac outburst, he dismissed critics of his policy towards the Kurds as traitors and foreign agents? Was Putin not defecating in public when, in a well-calculated gesture of vulgarity aimed at boosting his popularity at home, he threatened a critic of his Chechen policies with medical castration? Not to mention Boris Johnson …

This coming-open of the obscene background of our ideological space (to put its somewhat simply: the fact that we can now more and more openly make certain statements—racist, sexist, etc.—that, until recently, belonged to the private sphere) in no way means that the time of mystification is over, that now ideology openly shows its cards. On the contrary, when obscenity penetrates the public scene, ideological mystification is at its strongest: the true political, economic, and ideological stakes are more invisible than ever. Public obscenity is always sustained by a concealed moralism. Its practitioners secretly believe they are fighting for a cause, and it is at this level that they should be attacked.

Remember how many times the liberal media announced that Trump had been caught with pants down and had committed political suicide (by mocking the parents of a dead war hero, by boasting about pussy grabbing, etc.). Arrogant liberal commentators were shocked at how their continuous acerbic attacks on Trump’s vulgar racist and sexist outbursts, factual inaccuracies, and economic nonsense did not hurt him at all, but may have even enhanced his popular appeal. They missed how identification works: we as a rule identify with another’s weaknesses, not only, or even not principally, with their strengths. So the more Trump’s limitations were mocked, the more ordinary people identified with him and perceived attacks on him as condescending attacks on themselves. To ordinary people, the subliminal message of Trump’s vulgarities was “I am one of you!,” while ordinary Trump supporters felt constantly humiliated by the liberal elite’s patronizing attitude towards them. As Alenka Zupančič put it succinctly, “The extremely poor do the fighting for the extremely rich, as it was clear in the election of Trump. And the left does little else than scold and insult them.”7 Or, we should add, the left does what is even worse: it patronizingly “understands” the confusion and blindness of the poor … This left-liberal arrogance explodes at its purest in the new genre of political-comment-comedy talk show (Jon Stewart, John Oliver …), which mostly enacts the pure arrogance of the liberal intellectual elite. As Stephen Marche put it in LA Times:

Parodying Trump is at best a distraction from his real politics; at worst it converts the whole of politics into a gag. The process has nothing to do with the performers or the writers or their choices. Trump built his candidacy on performing as a comic heel—that has been his pop culture persona for decades. It is simply not possible to parody effectively a man who is a conscious self-parody, and who has become president of the United States on the basis of that performance.8

In my past work, I used a joke from the good old days of really-existing socialism that was popular among dissidents. In Mongol-occupied Russia in the fifteenth century, a farmer and his wife walk along a dusty country road. A Mongol warrior on a horse stops at their side and tells the farmer that he will now rape his wife. He then adds: “But since there is a lot of dust on the ground, you should hold my testicles while I’m raping your wife, so that they will not get dirty!” After the Mongol finishes his job and rides away, the farmer starts to laugh and jump with joy. The surprised wife asks him: “How can you be jumping with joy when I was just brutally raped in your presence?” The farmer answers: “But I got him! His balls are full of dust!” This sad joke tells of the predicament of dissidents: they thought they are dealing serious blows to the party nomenklatura, but all they were doing was getting a little bit of dust on the nomenklatura’s testicles, while the nomenklatura went on raping the people … And can we not say exactly the same about Jon Stewart and company making fun of Trump—do they not just get dust on his balls, or in the best of cases scratch them?

The problem is not that Trump is a clown. The problem is that there is a program behind his provocations, a method to his madness. The vulgar obscenities of Trump and others are part of their populist strategy to sell this program to ordinary people, a program which (in the long term, at least) works against ordinary people: lower taxes for the rich, less healthcare and workers’ protection, etc. Unfortunately, people are ready to swallow many things if they are presented to them through obscene laughter and false solidarity.

The ultimate irony of Trump’s project is that MAGA (Make America Great Again) effectively amounts to its opposite: make the US part of BRICS, a local superpower interacting on equal footing with other new local superpowers (Russia, India, China). An EU diplomat was right to point out that, with Trump’s victory, Europe is no longer the US’s “fragile little sister.” Will Europe find the strength to oppose MAGA with something that could be called MEGA: “Make Europe Great Again,” through resuscitating its radical emancipatory legacy?

The lesson of Trump’s victory is the opposite of what many liberal leftists have claimed: (whatever remains of) the left should get rid of its fear that it will lose centrist voters if it is perceived as too extremist. It should clearly distinguish itself from the “progressive” liberal center and its woke corporatism. To do this brings its own risks, of course: a state can end in a tripartite division with no big coalition possible. However, taking this risk is the only way forward.

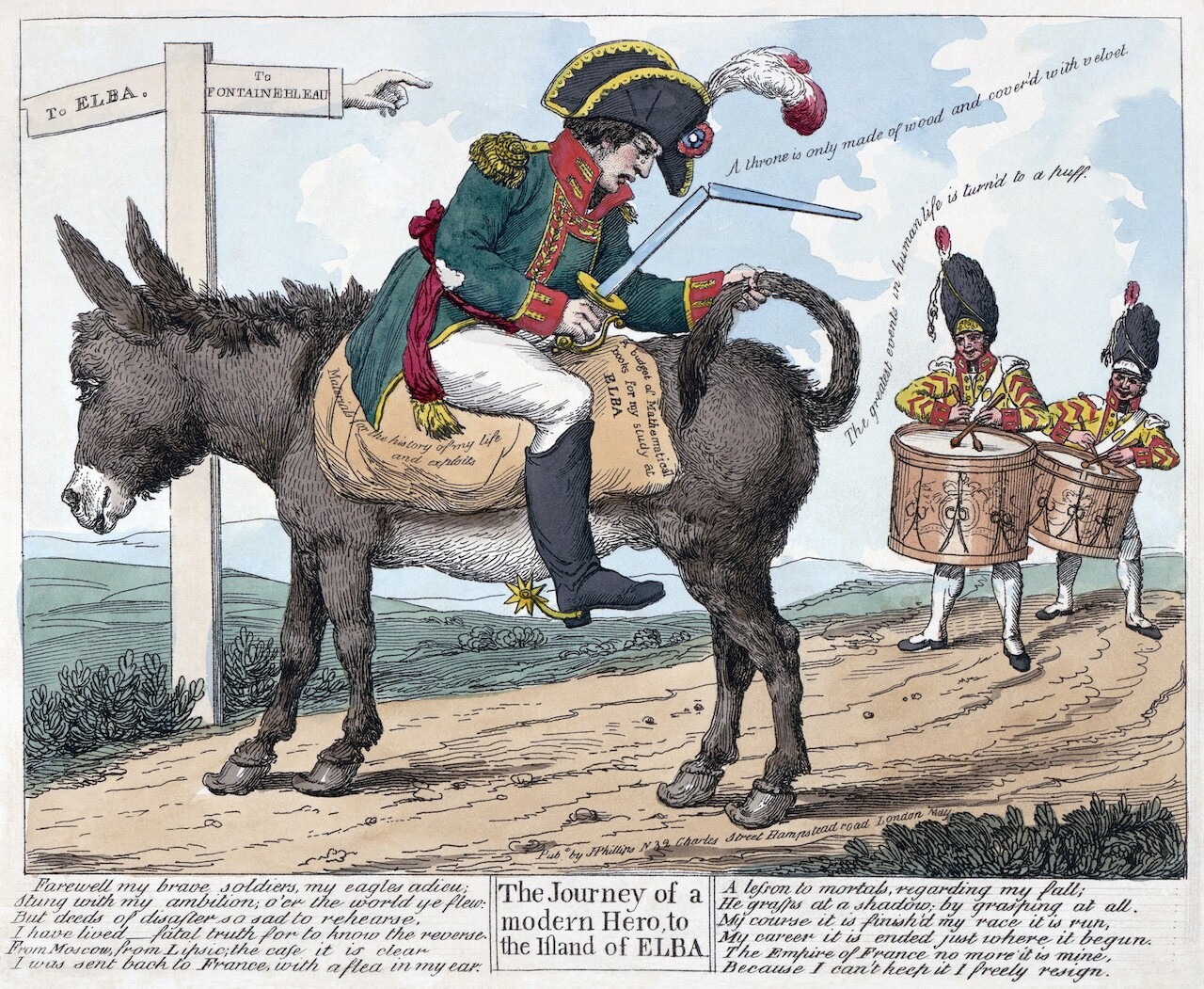

Hegel wrote that through its repetition, a historical event asserts its necessity. When Napoleon lost in 1813 and was exiled to Elba, this defeat may have appeared as something contingent: with better military strategy he might have won. But when he returned to power again and lost at Waterloo, it became clear that his time was over, that his defeat was grounded in a deeper historical necessity. The same goes for Trump: his first victory could still be attributed to tactical mistakes, but now that he won again, it should become clear that Trumpian populism expresses a historical necessity.

Many commentators expect that Trump’s reign will be marked by new shocking catastrophic events, but the worst possibility is that there will be no great shocks: Trump will try to finish the ongoing wars (enforcing a peace in Ukraine, etc.), the economy will remain stable and perhaps even bloom, tensions will be attenuated and life will go on … However, a whole series of federal and local measures will continuously undermine the existing liberal-democratic social pact and change the basic fabric that holds the US together—what Hegel called Sittlichkeit, the set of unwritten customs and rules of politeness, truthfulness, social solidarity, women’s rights, etc. This new world will appear as a new normality, and in this sense Trump’s reign may well bring about the end of the world, of what was most precious in our civilization.

So let’s conclude with a vulgar and cruel joke that perfectly renders our predicament. After her husband underwent a long and risky surgery, a woman approaches the doctor (who is her friend) and inquires about the outcome. The doctor begins: “Your husband survived, he will probably live longer than you. But there are some complications: he will no longer be able to control his anal muscles, so shit will drip continuously out of his anus. There will also be a continuous flow of a bad-smelling yellow jelly from his penis, so any sex is out. Plus his mouth will malfunction and food will be falling out of it …” Noting the growing expression of worry and panic on the wife’s face, the doctor taps her on the shoulder in a friendly way and smiles: “Don’t worry, I was just joking! Everything is okay, he died during the operation.” If we replace the doctor with Trump, who promises to cure our democracy, this is how he will explain the outcome of his reign: “Our democracy is well and alive, there are just some complications: we have to throw out millions of immigrants, limit abortion to make it de facto impossible, use the National Guard to crush protests … Don’t worry, I was just joking, democracy died during my reign!”

V. I. Lenin, “On Ascending a High Mountain,” 1922 →.

Private communication.

Aaron Schuster, “Beyond Satire: The Political Comedy of the Present and the Paradoxes of Authority,” in William Mozzarella, Eric Santner, and Aaron Schuster, Sovereignty, Inc. Three Inquiries in Politics and Enjoyment (University of Chicago Press, 2020), 234.

Private communication.

Private communication.

Adrian Johnston, Infinite Greed: The Inhuman Selfishness of Capital (Columbia University Press, 2024), 161.

Alenka Zupančič, “Back to the Future of Europe,” in The Final Countdown: Europe, Refugees, and the Left, ed. Jela Krečič (Irwin and Vienna Festwochen, 2017), 28.

Stephen Marche, “The Left Has a Post-Truth Problem Too. It’s Called Comedy,” Los Angeles Times, January 6, 2017 →.