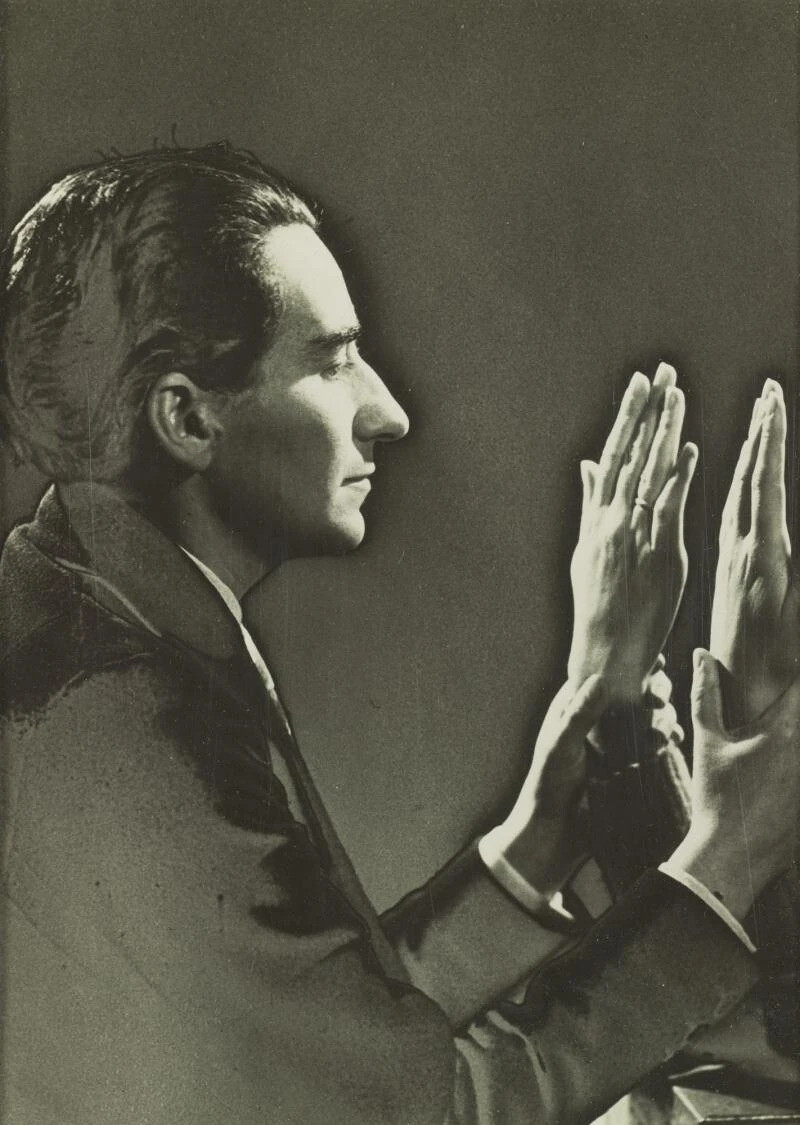

Man Ray, Dr. Charlotte Wolff (c. 1935)

In his 1985 talk “Heidegger’s Hand,” Jacques Derrida uses hands as a starting point to explore sexual difference (Geschlecht). Derrida revisits the roots of phenomenology through the prism of the hand. While writing Being and Time (1927), Heidegger was obsessed with hands. According to Derrida, thinking for Heidegger is “hand-work”: “Every motion of the hand in every one of its works carries itself (trägt sich) through the element of thinking, every bearing of the hand bears itself (gebärdet sich) in that element. All the work of the hand is rooted in thinking.”1

Derrida proposes that Heidegger’s central concepts are all connected to the hand, such as presence-at-hand (Vorhandenheit), action (Handeln), and truth (Verbergung/Entbergung): “The hand comes to its essence only in the movement of truth, in the double movement of what hides and causes to go out of its reserve.”2 Embodying Heidegger’s movement of truth, the opening of the palm both reveals and conceals. Derrida also notes that Heidegger refused to use a typewriter, clutching his pen in several photographs.

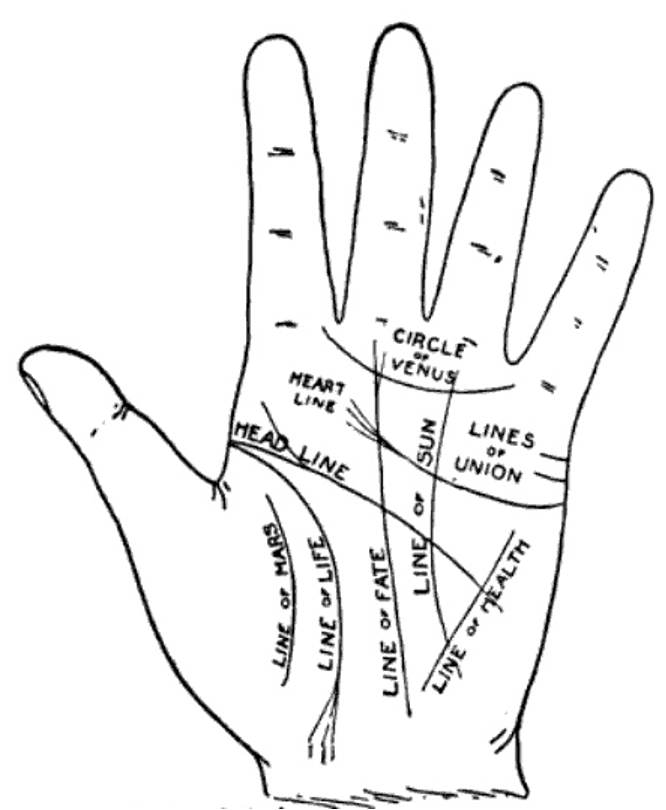

What is a philosopher’s touch? And what would a philosophy of the hand entail? Sam Dolbear’s Hand that Touches This Fortune Will: A Theory and History of Hand Reading after Charlotte Wolff (2024) envisions such a project. The book is a collection of vignettes and a critical guide through the cosmos of Charlotte Wolff (1897–1986), a largely forgotten German-British palmist and sexologist. It comes with a chart for reading your own palm, mapping zones like the Heart Line, Ring of Venus, and Finger of Jupiter. In palmistry, the hand is an index of the psyche—a microcosm with planetary meaning.

Hand that Touches This Fortune Will celebrates the hand as an intimate organ of encounter, capable of opening, reaching out, being touched, and holding. Dolbear reconstructs friendship networks as if they stretch like fingers from a shared palm. His textual collage interweaves the life of Wolff with those whose hands she read, including Walter Benjamin, Man Ray, Antonin Artaud, Aldous Huxley, Romola Nijinsky, T. S. Eliot, Virginia Woolf, and many invisible and unnamed acrobats, department-store managers, delinquents, and zoo animals. Dolbear assembled their traces from the perspective of their palms.

Wolff’s theory of the human hand, Dolbear emphasizes, was both pioneering and highly controversial, by turns empowering and oppressive. Wolff lived many lives in one. She was a lesbian activist, a Jewish Quaker, a scientist, and an occultist. She was also among the first women to appear on British TV in 1937. With a heavy German accent, Wolff evaluates her subject’s hands on camera, identifying a personality dominated by the Zone of Instinct: “I imagine that you could find your way alone in the dark.” “Yes, I can.” “And by the shape of your little finger that you have a sense of hearing as a horse.”

Born into a middle-class Jewish family in West Prussia, Wolff grew up in Danzig. She studied medicine, philosophy, and literature, attending Heidegger’s seminars in Freiburg. In 1926, she began working as a physician in Berlin’s working-class areas and joined the Association of Socialist Physicians, treating sex workers. She became interested in psychotherapy, queer sexology, palmistry, and chirology. Wolff, openly lesbian, frequented “homo-bars” and gay clubs with her friend Walter Benjamin.3

When the Nazis came to power, she stopped working at a birth control clinic and became Head of the Institute for Electro-Physical Therapy in Neukölln. At that time, electromagnetic concepts entered her handreadings. The Gestapo raided Wolff’s apartment, interrogating her for dressing as a man, but released her when an officer recognized his wife’s doctor. After obtaining a passport, Wolff fled to Paris. In Paris, unable to practice medicine, she made ends meet through hand analysis. She later moved to Britain, where she lived until her death, writing books on chirology, novels, and a biography of Magnus Hirschfeld.

Wolff was inspired by an emerging interest in gesture and expression in the 1920s, such as Ludwig Klages’s graphology, the analysis of handwriting. Like graphology, palmistry documents frozen gestures, suggesting that the essence of a body’s movements becomes inscribed on the hand as lines. I first came across Wolff’s name while reading about occult practices in surrealism.4 When Wolff arrived in Paris, she soon became friends with the surrealists. She was initiated into the circle by Pierre Klossowski and his brother, the painter Balthus. Wolff met André Breton, Picasso, Dora Maar, Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dalí, Antonin Artaud, Man Ray, and Robert Desnos.

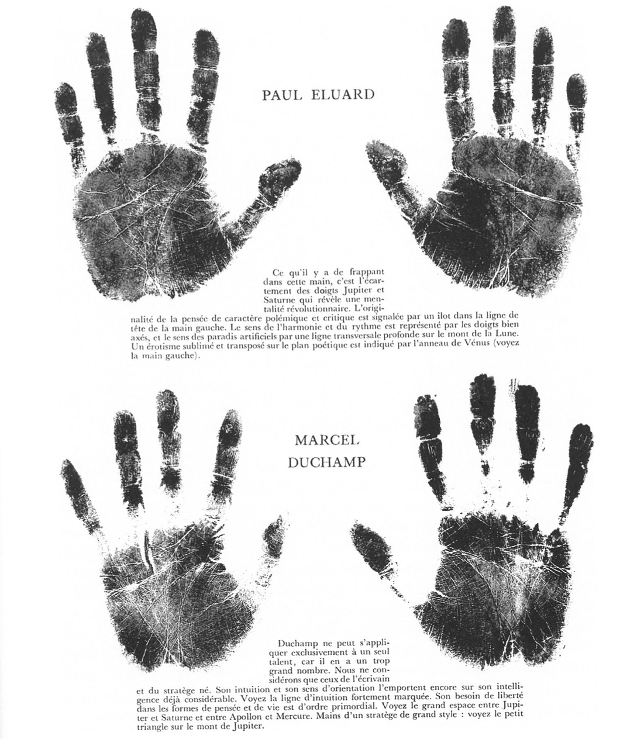

Hands were a leitmotif in surrealism. In Man Ray’s film L’Étoile de mer (1928), for instance, the open palms of Ray’s lover Kiki de Montparnasse are marked with black lines. Wolff published an article in the surrealist magazine Minotaure, “Psychic Revelations of the Hand” (1935), which was translated by Klossowski. She presents some of her handprints along with her system of reading. Fittingly, Hans Bellmer’s images of fragmented dolls precede the text.

Wolff read the hands of many surrealists, including Paul Éluard, Breton, and Duchamp. Picasso refused to have his hands read by Wolff. Artaud’s fingers, Wolff recorded, “grow widely apart from each other, and indicate a materialistic conception of life.”5 Artaud is a Mars type, she concludes, “childlike, visited by fits of depression, in search of an artificial paradise.”6 Artaud’s Mount of Venus reveals “a desire to protect the defenseless.”7 Man Ray is diagnosed with “delicate health,” revealed by a faint Life Line.8 Balthus’s fingers, for Wolff, indicate “a relation to the world that is childlike and without worldly ambition.”9 Breton is a Venus type, with a dominant subconscious.

The technique is easy: you spread Vaseline over the palm and fingers, press the hand on paper, shake copper oxide onto the greased print, and fix it. The print blurs the boundaries between interior and exterior, contours and expression. The handprint, Dolbear writes, is a unique, “crystalline record that can be integrated into a semiotic system of fate and character.”10 The lines in the hand are both an expression (Ausdruck) and impression (Eindruck) of fate.

Wolff’s Parisian friendship circles were glamorous. The fashion writer Helen Grund, married to Franz Hessel, drove Wolff in a sports car to the south of France where they partied with the Mann family and Maria and Aldous Huxley. The surrealists associated Wolff’s work with “feminine clairvoyance,” complicated by the fact that she was openly lesbian and dressed like a man.11 In 1935, Wolff visited the Huxleys in London. Wolff moved to Britain permanently in October 1936, where Julian Huxley arranged her study of primates at the London Zoo.

Halfway through the book, I am gripped by the desire to have my palm read. My local palmist down the road advertises himself as “India’s No. #1 Spiritual Healer & Fortune Teller.” His expertise lies in “removing black magic & generation curses”—just what I need. He also offers astrology, fortune telling, and horoscopes. After multiple phone calls, I am allowed to meet the master in the back of a Dalston internet café, next door to a nail bar. I stumble down a dimly lit basement, as the sound of Nigerian drums beckon below. I clutch a ten-pound note as payment for the palmist, not quite crossing his palm with silver. I reflect on the nature of change. Outside, East London’s gay and trans couples walk hand in hand.

I step into his office, a liminal space between cloakroom and temple, decked out with images of Hindu gods. As I offer my palm to the master, all that separates us from the outside world is a thin red velvet curtain. “For every problem, there is a solution,” I am promised. I sit down, he asks me to throw six shells three times. My date of birth and the constellation of shells allow the palmist to draw up a table with magical numbers.

My left palm lies stretched out on the table in front of him. He “reads” it without touching it. The future looks good: a long life, success next year, “money comes and money goes.” He also noticed my “good peacock eyes.” There is only one problem: evil enemies. The master offers to protect me from a particularly jealous girl for another thirty pounds. I decline and his consultation ends with asking: “Any doubts?”

In his preface to Wolff’s Studies in Hand-Reading (1936), Aldous Huxley writes that chirology was a “science of intuition.”12 Similar experiences, he contends, leave similar traces on our hands. Wolff would soon meet her namesake, Virginia Woolf, one of the many memorable anecdotes in Dolbear’s book. Wolff read her hand and “for two hours poured forth a flood of connected and intense discourse.”13

Handreading is a practice in between medical analysis and mysticism. Different forms of chiromancy or palmistry are practiced in various esoteric traditions, modern occultism, and New Age beliefs. As Peter Forshaw writes in Occult: Decoding the Visual Culture of Mysticism, Magic & Divination (2024), palmistry “looks for significance in the lines on the palm and takes note of the length and shape of the fingers and nails, as well as the features of the hand in general.”14 All those elements are used to determine a person’s character and predict their future.

Diagram of the chief lines of the hand as used in palmistry. From Elmo Jean La Seer, Illustrated Palmistry: The Science of the Hand & Its Lines, 1904. Public domain.

Each palmist has their own system of dividing the hand in several zones with planetary significance. Wolff was keen to emphasize the scientific nature of her own method of hand analysis. She did not see herself as an occultist. The “charlatan phase of palm reading,”15 for Wolff, the “abracadabra of flesh,”16 was as necessary to a science of the hand as alchemy was to chemistry:

The psychology of the hand is like medicine, an art as well as a science, and accordingly intuition plays a part in it. But intuition must not be confused with clairvoyance. Intuition may be defined as the instantaneous synthesis below the level of consciousness of observed details leading to the formation of judgments, with only the results rising into consciousness. There is nothing supernatural about it.17

Every part of the palm represents a planet in miniature: the thumb Venus; the index finger Jupiter, representing power; the middle finger Saturn, or knowledge; the ring finger the sun or Apollo, indicating luck; the little finger Mercury; the center of the palm Mars; and the side the Moon. The Heart Line indicates feelings and friendship, the Head Line thinking, the Life Line health. The Line of Fate guides our direction, the Lines of Affection love and relationships.

From the 1960s onwards, Wolff’s interest shifted to sexology. She completed two autobiographies, a novel on lesbian love, a study on bisexuality, and a monumental biography of Magnus Hirschfeld, published in 1986. In feminist activist circles, she was known as the last survivor of the Weimar Republic. Handreading turns into a seismograph of sexuality. Wolff emphasized that hands are not one but two. Similarly, Derrida in his talk remarked how Heidegger suppressed this dual nature, treating the hand as singular: “Hands are organs. But the hand is not an organ.”

In occultism, the left-hand path points to black magic. In Wolff’s system, left and right have sexual connotations. The left hand is female and passive, the right male and active. Many palmists believe that the left remains as it is from infancy while the right gets inscribed by our experiences. Wolff associates the two hands with our essentially double-sexed, hermaphroditic nature, drawing on Plato’s Symposium in her study on bisexuality. Dolbear analyzes how Wolff’s sexology of the hand assigned to the palm an atavistic meaning. In Wolff’s evolutionary biology, the palm is at the origin, preceding the fingers.

Wolff’s self-fashioning as a scientist hides the inside of her own palm: Wolff the mystic. During her last months in Nazi Germany, she underwent Jungian analysis. One of the most striking childhood memories is that of a spiritual revelation. Walking the streets of Danzig, she felt her third eye opening:

A sense of immeasurable happiness filled me. I breathed deeply and heavily, and in doing so my body appeared to change. I became taller than I really was, my hands, larger than before, stretched out with palms turned upwards. But the strangest sensation was that which affected my brow: I felt a bluish crystal just above my eyes at the root of my nose. I called it the amethyst. I have an amethyst in my head.18

In his preface to Studies in Hand-Reading, Aldous Huxley compared Woolf to a medieval scryer able to gaze into other minds. Wolff’s doors of perception were wide open. Our palms can connect us with the cosmos in unforeseen ways. The longer we look at hands, Dolbear writes, the more they appear like vegetables or strange creatures. Hands are always on the edge of consciousness, suspended between touch and fantasy.

While reading Hand that Touches This Fortune Will, I began to dream of hands. In one dream, someone’s right hand only had four fingers; the pinky finger was replaced by a silver steel prosthetic that reached almost to the wrist. The prosthetic made no sound when it moved. A prosthetic suddenly appears toward the end of the book. It replaces a missing hand, enabling its wearer to work without ever tiring. Like the glove, the prosthetic conceals a limb, averting feelings of disgust.

This fear of contamination has clear class connotations. Most of the hands that Wolff read were bourgeois hands, showing little traces of manual labor, while work deforms our hands, making them swollen, dry, wrinkled, and cracked. They erode in their contact with materials and the environment. Reading the hands of a worker, Dolbear writes, “is to read the somatic imprint of work and its orbiting materials on the body.”19

In June 1924, Wolff boarded a train to Moscow via Riga, similar to the journey Benjamin would undertake two years later, the same year Hirschfeld went. Wolff hoped to interest Soviet artists in an essay she wrote on Viking Eggeling’s Symphonie Diagonale (1924), a film she brought with her to the USSR. Her friend Käthe Kollwitz wrote a letter of recommendation. If anything, Soviet Russia released a bout of agoraphobia in Wolff that she had treated in an Austrian sanatorium.

In his sci-fi-infused book On Idols and Ideals (1968), the Soviet philosopher Evald Ilyenkov describes the hand as the most perfect organ for object-oriented activity. Drawing on Spinoza, Ilyenkov insists that thinking does not happen in the brain. Like a jar growing under the hands of a potter, thinking arises from the material interactivity of body, clay, and tools. Ilyenkov’s enactive conception of a thinking body transcends any mind-body dualism.

Capitalism, Ilyenkov writes, consumes the energy of the entire body—our hands, brain, and nerves. Some people work all their life “with their head” while others work “with their hands.”20 Even this fragmentation might be optimized further by capitalists, demanding “hands, for whom it would be useful to divide its tasks between the Right and the Left, and then move on to more dispersed tasks with the Pinky and Index fingers, and so on.”21

The Buddhist scripture Udāna is famous for its story of the blind men and an elephant. A group of blind men imagine what an elephant looks like by touching it with their hands. Based on their fragmented experience of the side, leg, tusk, ear, or head, they each describe a different animal. To one blind man, the elephant is a snake, to another a pillow, a wall, or a tree trunk.

At the radical school for deaf-blind children at Zagorsk, Ilyenkov experimented with forms of communication without language. As Emanuel Almborg’s film Talking Hands (2016) wonderfully captures, the deaf-blind children speak through their hands and with the help of tactile machines. In Ilyenkov’s socialist philosophy of the hand, we see through the eyes and touch through the hands of all people. Thinking is an embodied and collective activity.

Wolff, too, believed that the hand was an organ of thinking. As the visible organ of the brain—an “organ between fin and wing”22—hands can grasp and touch, reach and think. As Derrida put it, thinking is “hand-work”: “Thinking is not cerebral or disincarnate; the relation to the essence of Being is a certain, I would say, manner, a certain manner of Dasein as Leib, as body, as living body.” The hand, in Heidegger, is more than a “bodily organ of gripping.” While Ilyenkov made the human hand the supreme organ of the collective thinking body, Wolff ultimately used the hand as a tool to separate and classify people into types.

Dolbear does not gloss over the shortcomings and dead ends of Wolff’s philosophy of the hand. Palm reading can be violent, ascriptive, and pathologizing. Wolff was both a friend to many and a doctor who maintained distance from her subjects, sometimes reading palms through a curtain—merely fragmented, disembodied hands. Dolbear reconstructs how the art of palmistry influenced what Michel Foucault called disciplinary societies. Fingerprinting techniques, as just one example, were introduced after the 1857–58 rebellion against the British East India Company to identify colonial subjects and were eventually adopted by the police.

In her works The Human Hand (1942) and A Psychology of Gesture (1945), Wolff employed pre-Nazi racial sciences, eugenics, and biologistic profiling. Dolbear’s critical readings of Wolff are eye-opening. He notes that her use of racist and ableist terms is not merely incidental; it is integral to “a complex system that maps hands with types.”23 The modern state learned to stamp out hands in ink and take fingerprints, identifying subjects as prisoners, workers, or criminals. The palmist, too, exerts power over the hands they read. Perhaps our palms reveal what we wish to conceal?

Our hands, Dolbear writes, “betray” us, from Latin tradere, to hand over.24 Mirroring the duality of hands, Wolff perceived herself in a double exile, as a Jew and a lesbian. Wolff rarely spoke about the fate of her family post-1933. In 1967, she disclosed to The Guardian that her immediate family had died of natural causes, but many aunts, uncles, and cousins were murdered in Theresienstadt. “In some of her later work,” Dolbear writes, “Wolff observed the hand of patients diagnosed with manic depression, how they wrung, pressed and interlocked them.”25

In contemporary capitalism, the hand reflects the division of labor, the split between skilled and unskilled, intellectual and manual. In Ilyenkov’s philosophy, the human hand is unique in its plasticity, able to transform and adapt to the objects it holds, touches, and grasps. In his final text What is Personality? (1979), Ilyenkov described personality as a “knot” (uzelok), tied in a network of mutual relations between the “I” and the “non-I.” The body, Ilyenkov writes, is “at least two such bodies—‘I’ and ‘you,’ merged as if they were in one body of social and human ties, relations, interrelations.”26 Maybe our hands can become interlaced, too, reassembling a collective thinking body through touch.

Jacques Derrida, “Heidegger’s Hand,” lecture, Cornell University, September 11, 1985 →.

Derrida, “Heidegger’s Hand.”

Wolff, quoted in Sam Dolbear, Hand that Touches This Fortune Will: A Theory and History of Hand Reading after Charlotte Wolff (Ma Bibliothèque, 2024), 78.

M. E. Warlick, “Palmistry as Portraiture: Dr. Charlotte Wolff and the Surrealists,” Surrealism, Occultism and Politics: In Search of the Marvellous, ed. Tessel M. Bauduin et al. (Routledge, 2018).

Quoted in Dolbear, Hand that Touches, 158.

Dolbear, Hand that Touches, 110f.

Wolff, quoted in Dolbear, Hand that Touches, 91.

Wolff, quoted in Dolbear, Hand that Touches, 111.

Wolff, quoted in Dolbear, Hand that Touches, 36.

Dolbear, Hand that Touches, 93.

Warlick, “Palmistry as Portraiture,” 57.

Quoted in Dolbear, Hand that Touches, 130.

Woolf, quoted in Dolbear, Hand that Touches, 127.

Peter Forshaw, Occult: Decoding the Visual Culture of Mysticism, Magic & Divination (Thames & Hudson, 2024), 238.

Dolbear, Hand that Touches, 125.

Wolff, quoted in Dolbear, Hand that Touches, 125.

Charlotte Wolff, The Human Hand (Methuen & Co, 1942), 6.

Cited in Dolbear, Hand that Touches This Fortune Will, 130.

Dolbear, Hand that Touches, 99.

Evald Ilyenkov, Ob idolakh i idealakh (Izdatel’stvo Politicheskoi Literatury, 1968), 38.

Ilyenkov, Ob idolakh i idealakh, 38.

Wolff, quoted in Dolbear, Hand that Touches, 194.

Dolbear, Hand that Touches, 84.

Dolbear, Hand that Touches, 63.

Dolbear, Hand that Touches, 171.

Evald Ilyenkov, “Chto zhe takoe lichnost’?” Sobranie sochinenii, vol. 5 (Kanon+, 2021), 393f.