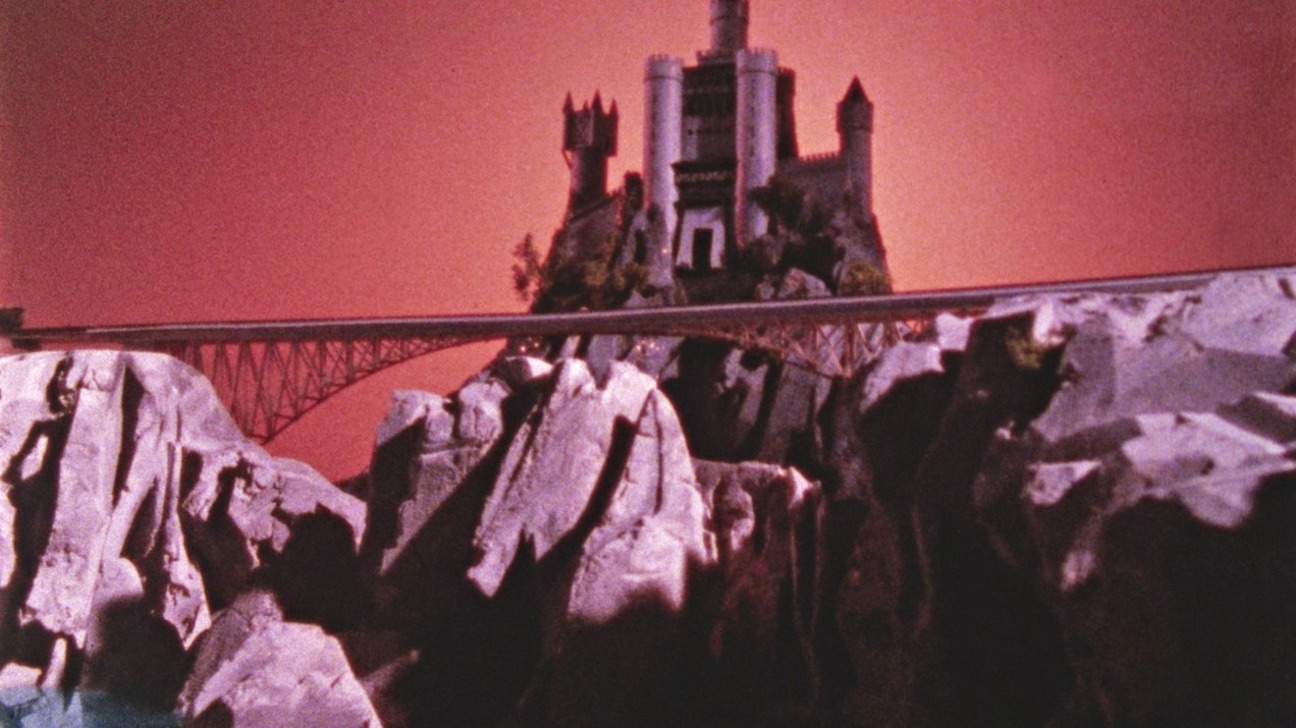

Still from Blue Velvet, dir. David Lynch, 1986.

In art history, the Pre-Raphaelites function as the paradoxical border case of an avant-garde overlapping with kitsch. They were first perceived as bearers of an anti-traditionalist revolution in painting, breaking with the entire tradition from the Renaissance onwards, only to be devalued shortly thereafter—with the rise of impressionism in France—as the very epitome of damp Victorian pseudo-romantic kitsch. This low esteem lasted till the 1960s, i.e., until the emergence of postmodernism. How was it, then, that they became “readable” only retroactively, from the postmodernist paradigm?

In this respect, the crucial painter is William Holman Hunt, usually dismissed as the first Pre-Raphaelite to sell out to the establishment, becoming a well-paid producer of saccharine religious paintings (The Triumph of the Innocents, etc.). However, a closer look confronts us with an uncanny, deeply disturbing dimension of his work: his paintings produce a kind of uneasiness or indeterminate feeling that, in spite of their idyllic and elevated “official” content, there is something amiss.

Let us take the Hireling Shepherd, apparently a simple pastoral idyll depicting a shepherd engaged in seducing a country girl, and for that reason neglecting to care for a flock of sheep (an obvious allegory of the Church neglecting its lambs). The longer we observe the painting, the more we become aware of a great number of details that bear witness to Hunt’s intense relationship to enjoyment, to life-substance, i.e., to his disgust at sexuality. The shepherd is muscular, dull, crude, and rudely voluptuous; the cunning gaze of the girl indicates a sly, vulgarly manipulative exploitation of her own sexual attraction; the all-too-vivacious reds and greens mark the entire painting with a repulsive tone, as if we were dealing with turgid, overripe, putrid nature. It is similar to Hunt’s Isabella and the Pot of Basil, where numerous details belie the “official” tragic-religious content (the snake-like head, the skulls on the brim of the vase, etc.). The sexuality radiated by the painting is damp, “unwholesome,” and permeated with the decay of death. It plunges us into the universe of the filmmaker David Lynch.

Lynch’s entire “ontology” is based on the discordance or contrast between reality, observed from a safe distance, and the absolute proximity of the real. His elementary procedure consists in moving forward from an establishing shot of reality to a disturbing proximity that renders visible the disgusting substance of enjoyment, the crawling and twinkling of indestructible life—in short, the lamella. Recall the opening sequence of Blue Velvet. After the shots that epitomize the idyllic small American town and the father’s stroke while he waters the lawn (when he collapses, the jet of water uncannily recalls surreal, heavy urination), the camera approaches the grass surface and depicts the bursting life, the crawling of insects and beetles, their rattling and devouring of grass. At the very beginning of Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, we encounter the opposite technique, which nonetheless produces the same effect. First we see abstract white protoplasmic shapes floating in a blue background, a kind of elementary form of life in its primordial twinkling; then the camera slowly moves away and we become aware that what we were seeing was an extreme close-up of a TV screen.1 Therein lies the fundamental feature of postmodern hyperrealism: the very over-proximity to reality brings about a “loss of reality.” Uncanny details stick out and perturb the pacifying effect of the overall picture.2

The second feature, closely linked to the first, is contained in the very designation “Pre-Raphaelitism”: the reaffirmation of rendering things as they “really are,” not yet distorted by the rules of academic painting first established by Raphael. However, the Pre-Raphaelites’ own practice belies this naive ideology of returning to the “natural” way of painting. The first thing that strikes the eye in their paintings is a feature that necessarily appears to us, accustomed to modern perspective-realism, as a sign of clumsiness. The Pre-Raphaelite paintings are somehow flat, lacking the “depth” of space organized along the perspective lines that meet in an infinite point; it is as if the very “reality” they depict were not a “true” reality but rather structured as a relief. Another aspect of this same feature is the “dollish,” mechanically composite, artificial quality of the depicted individuals: they somehow lack the abyssal depth of personality we usually associate with the notion of “subject.” The designation “Pre-Raphaelitism” is thus to be taken literally, as an indication of the shift from Renaissance perspectivism to the “closed” medieval universe.

In Lynch’s films, the “flatness” of the depicted reality responsible for the cancellation of infinite-perspective openness finds its precise correlate or counterpart at the level of sound. Let us return to the opening sequence of Blue Velvet: its crucial feature is the uncanny noise that emerges when we approach the real. This noise is difficult to locate in reality. In order to determine its status, one is tempted to evoke contemporary cosmology, which speaks of noises at the borders of the universe. These noises are not simply internal to the universe; they are remainders or last echoes of the Big Bang that created the universe itself. The ontological status of this noise is more interesting than it may appear, since it subverts the fundamental notion of the “open,” infinite universe that defines the space of Newtonian physics. That is to say, the modern notion of the “open” universe is based on the hypothesis that every positive entity (noise, matter) occupies some (empty) space; it hinges on the difference between space as void and positive entities which occupy it, “fill it out.”

Space is here phenomenologically conceived as something that exists prior to the entities which “fill it out.” If we destroy or remove the matter that occupies a given space, this space as void remains. The primordial noise, the last remainder of the Big Bang, is on the contrary constitutive of space itself: it is not a noise “in” space, but a noise that keeps space open as such. If, therefore, we were to erase this noise, we would not get the “empty space” that was filled out by it. Space itself, the receptacle for every “inner-worldly” entity, would vanish. This noise is, in a sense, the “sound of silence.” Along the same lines, the fundamental noise in Lynch’s films is not simply caused by objects that are part of reality; rather, it forms the ontological horizon or frame of reality itself, i.e., the texture that holds reality together. Were this noise to be eradicated, reality itself would collapse. From the “open” infinite universe of Cartesian-Newtonian physics, we are thus back to the premodern “closed” universe, encircled, bounded, by a fundamental “noise.”

We encounter this same noise in the nightmare sequence of The Elephant Man. It transgresses the borderline that separates interior from exterior; the extreme externality of a machine uncannily coincides with the utmost intimacy of the bodily interior, with the rhythm of heart palpitations. This noise also appears after the camera enters the hole in the elephant man’s hood, which stands for the gaze. The reversal of reality into the real corresponds to the reversal of the look (the subject looking at reality) into the gaze; it occurs when we enter the “black hole,” the crack in the texture of reality.

We find the same paradox in a remarkable scene at the beginning of Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America, in which we see a phone ringing loudly. When a hand picks up the receiver, the ringing goes on—as if the musical life force of the sound is too strong to be contained by reality and persists beyond its limitations. Or, back to Lynch: recall a similar scene from Mulholland Drive in which a singer sings on stage Roy Orbison’s “Crying,” and when she collapses unconscious, the song goes on. What happens, however, when this flux of life-substance itself is suspended, discontinued?

Georges Balanchine staged a short orchestral piece by Anton Webern (they are all short) in which the music ended but the dancers continued to dance for some time in complete silence, as if they had not noticed that the music that provided the substance for their dance was already over—like the cartoon cat that continues to walk over the edge of the precipice, ignoring that it no longer has ground under its feet … The dancers who continue to dance after the music is over are like the living dead who dwell in an interstice of empty time: their movements, which lack vocal support, allow us to see not only the voice but silence itself. Therein resides the difference between the Schopenhauerian Will and Freud’s (death) drive: while Will is the substance of life, its productive presence, which is in excess of its representations or images, drive is a persistence which goes on even when the Will disappears or is suspended. Drive is the insistence that persists even when it is deprived of its living support, the appearance that persists even when it is deprived of its substance.

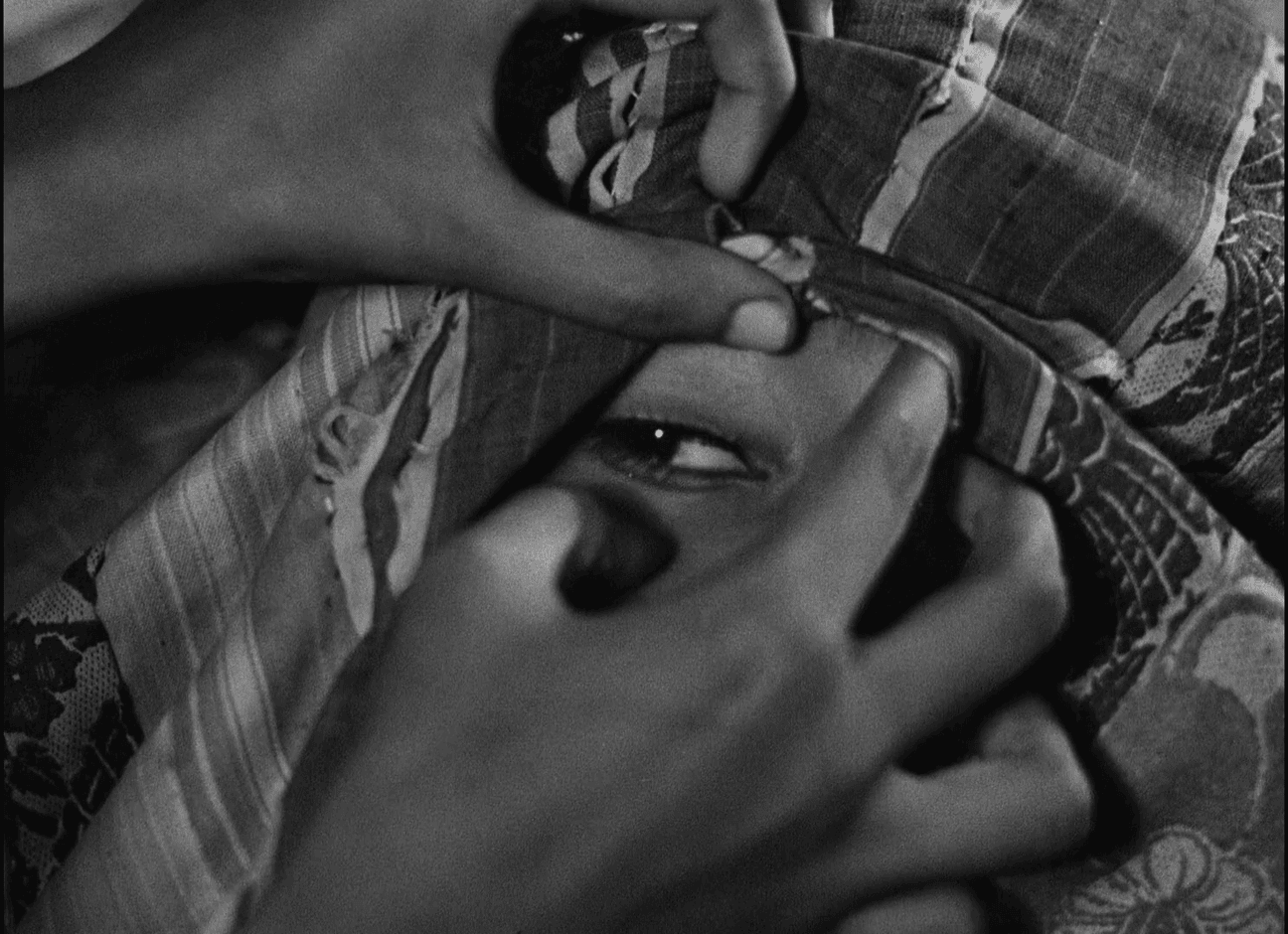

Sexual difference itself gets perturbed in such scenes. One is tempted to recall here the most disturbing scene in Lynch’s Wild at Heart, in which Willem Defoe harasses Laura Dern: although a man harasses a younger woman, a series of clues (Dern’s boyish face, Defoe’s obscenely distorted “cunt face”) signals that the underlying fantasy scenario is that of a vulgar overripe woman harassing an innocent boy. And what about the scene from Lost Highway in which the boyish Pete is confronted with a woman’s face, contorted by sexual ecstasy, displayed on a gigantic video screen? Perhaps the outstanding example of this confrontation of the asexual boy with the Woman is the famous sequence of shots, from the beginning of Ingmar Bergman’s Persona, of a preadolescent boy with large glasses examining with a perplexed gaze the giant unfocused screen-image of a feminine face. This image gradually shifts to the close-up of what seems to be another woman who closely resembles the first one—yet another exemplary case of the subject confronted with the phantasmatic interface-screen.

The original site of fantasy is that of a small child overhearing or witnessing parental coitus and feeling unable to make sense of it: What does all of this mean—the intense whispers, the bizarre sounds in the bedroom, etc.? The child fantasizes a scene that can account for these strangely intense fragments; recall the best-known scene from Lynch’s Blue Velvet, in which Kyle MacLachlan, hidden in the closet, witnesses the weird sexual interplay between Isabella Rosselini and Dennis Hopper. What he sees is a clear phantasmatic supplement destined to account for what he hears: When Hopper puts on a mask through which he breathes, is this not an imagined scene meant to account for the intense breathing that accompanies sexual activity? The fundamental paradox of fantasy is that the subject never arrives at the moment when they can say, “Okay, now I fully understand it. My parents were having sex. I no longer need a fantasy!” This is, among other things, what Lacan meant with his “Il n’y a pas de rapport sexuel” (There is no such thing as a sexual relationship). Every sense has to rely on some nonsensical phantasmatic frame; when we say, “Okay, now I understand it!,” what this ultimately means is: “Now I can locate it within my phantasmatic framework.”

This is why Lynch’s films defy understanding; herein resides their greatness. And this is also why, although Lynch has died, he will continue to haunt us for a long time as the living dead.

The same procedure was employed by Tim Burton in the outstanding credits sequence of Batman: the camera errs along nondescript, winding, unsmooth metal funnels; after it gradually backs off and acquires a “normal” distance from its object, it becomes clear what this object actually is: the tiny Batman badge.

The counter to this Lynchian attitude is perhaps the philosophy of Leibniz: Leibniz was fascinated by microscopes because they confirmed to him that what appears from the “normal,” everyday point of view to be a lifeless object is actually full of life. One has but to take a closer look at it, i.e., to observe the object from absolute proximity: under the lens of a microscope, one can perceive the wild crawling of innumerable tiny living things.