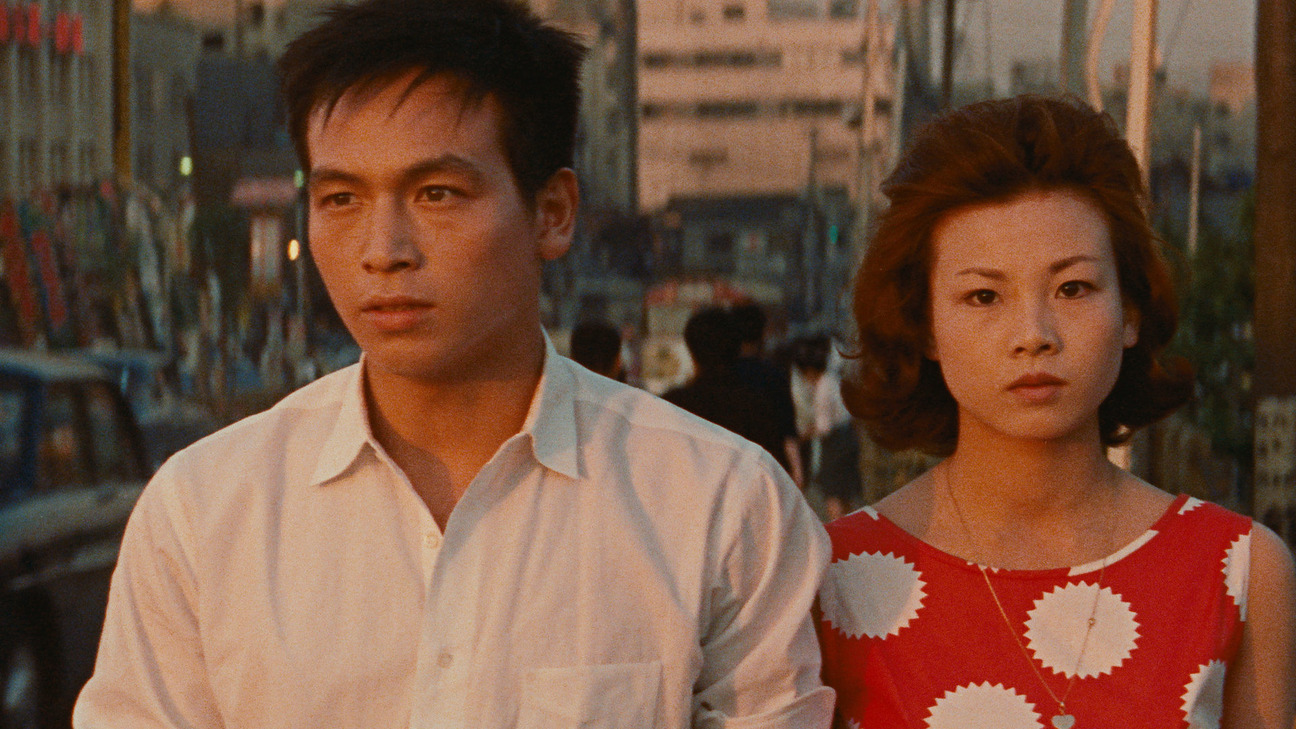

Still from Pier Paolo Pasolini, Mamma Roma (1962)

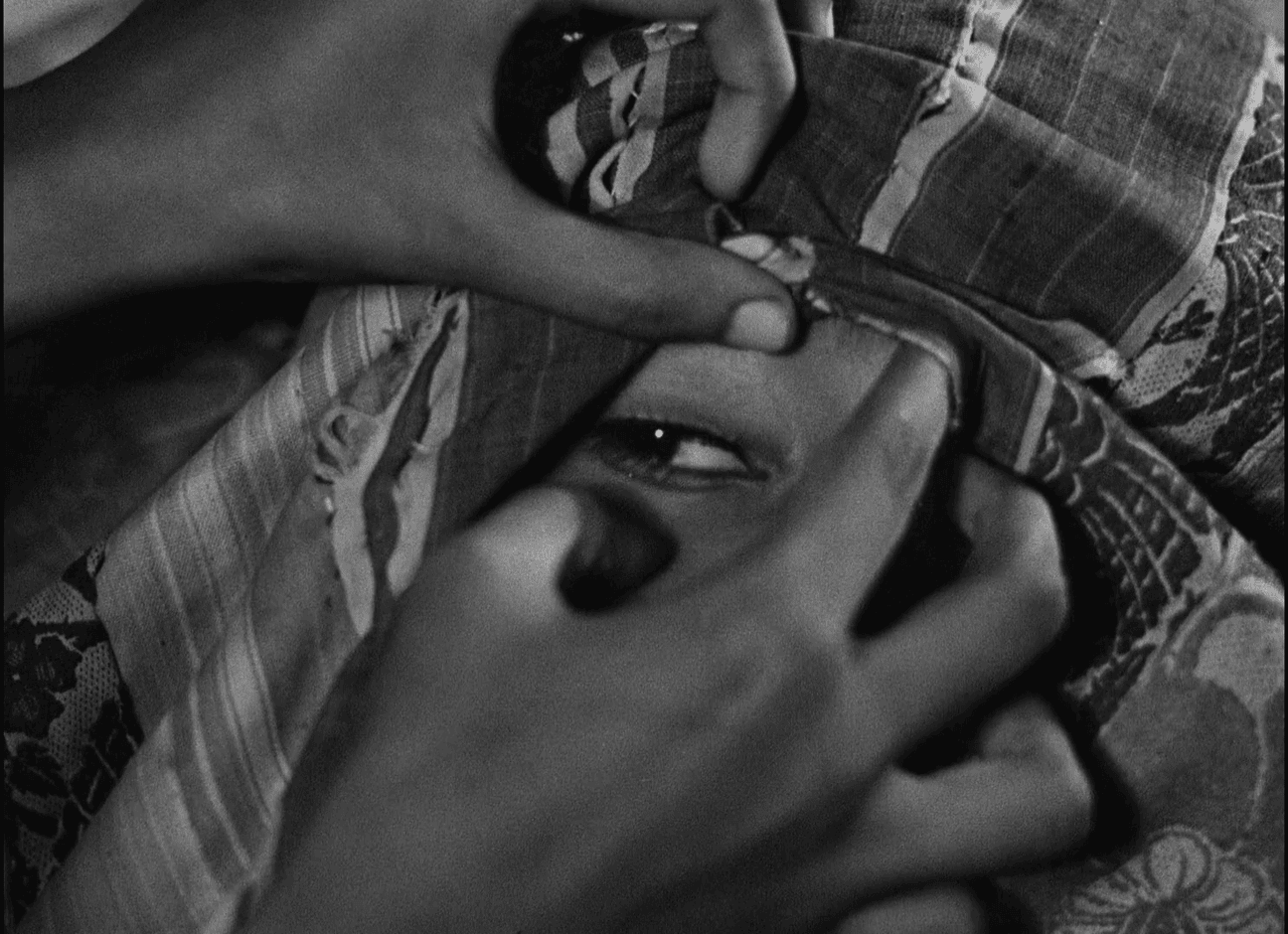

The image and the word in cinema are one and the same thing: a topos.1 The perception of it as one thing or as a thing (more or less) divided and dissociated depends on the location of the spectator. At times the distance which separates a clap of thunder from a flash of lightning seems incredible; that is, such a diachrony between image and sound seems incredible. I saw a dubbed version of the stupendous Tales of the Pale Moon of August,2 and the words dubbed from Japanese had nothing to do with the persons who were speaking; they happened in two completely different time frames. But one must not be deceived by these extreme examples nor by the more normal instances, that is, the majority of cases (films, particularly in Italy, precisely because of the dubbing, are always badly spoken). The thunder is a sort of regurgitation or yawn which hobbles behind the lightning. In reality the phenomenon of lightning and thunder is a single atmospheric phenomenon: cinema is, in other words, audiovisual.

I understand the charm of the rhetorical idea of cinema as pure image. In fact, even I myself make silent films with indescribable pleasure. But making silent films is nothing more than a metrical restriction, as, for example, terza rima in poetry, which infinitely reduces the possibility of speaking the speakable, causing the possibility of speaking the unspeakable to grow inordinately. The (antiquated) defenders of silent cinema as the only "optimum," thus, in conclusion, as precisely the rhetorical "norm"—attribute an ancillary function to the word in cinema, naturally assumed to be ORAL. As, for example, in melodrama. The words of Traviata, they say, are foolish and ridiculous, aesthetically not only devoid of worth, but rather, almost offensive to good taste; and yet that doesn't count for anything. It is the music that counts, they say. This statement seems so full of good sense and instead is completely senseless. Whoever says this ignores the "ambiguity" of the poetic word: the contrast between "meaning" and "sound" which cannot be eliminated. Poetry is (Valéry, quoted by Jakobson) "une exitation prolongée entre lc sens et le son."3 Therefore, every poem is metalinguistic, because every poetic word is an incomplete choice between its phonic value and its semantic value. The reversal of the relationships between contiguity and similarity (still Jakobson) multiplies inordinately the polyexpressiveness of the poetic word.

In conclusion: in every poem there is inevitably what is called "semantic expansion." This is pushed to a paroxysm in the symbolist poets, for example, but it is a phenomenon found in all the poetic languages of the world. It is the sound (spoken out loud or heard in the head, as a musician hears the music reading the score) which derails, deforms, propagates the meaning by other roads. Now music applied to words is simply the extreme example of what I have said. Music destroys the "sound" of the word and substitutes another for it, and this destruction is the first operation. Once it has taken the place of the sound of the word, it then takes care of effecting the "semantic expansion" of the word, and what a semantic expansion we have in the words of Traviata! If the "naked" sound of the word can expand the meaning of the word itself toward the "clouds" and create something which lies between the meaning "naked body" and the meaning "cloudy sky," you can imagine what a c from the diaphragm would make of the same word!

Words are therefore not at all ancillary in melodrama; they are extremely important and essential. Only that the hesitation between meaning and sound in them has the appearance of an option in favor of sound, and later this sound has been supplanted by a sound which is different from the phonic one, and which—being infinitely more sound—has infinitely greater possibilities of working semantic expansions. In cinema the word (with the exception of the least relevant instances of road signs and "credits") must be considered in its ORAL manifestation. This is what drives mad those who have not had occasion to read at least Morris.4 And who are therefore convinced that language is a privileged system unto itself, and not one of the many possible systems of signs. Now, for centuries we have been used to making aesthetic evaluations based exclusively on the WRITTEN word. It alone seems worthy to us of being not only poetic but also simply literary. Because in cinema instead the word is ORAL, it is naturally perceived as a product of little worth or actually despised. I would like to have seen these creatures of habit listen to the ORAL word of Homer when he recited his poems in a period in which neither writing nor printing had been invented. Well, certainly judgment was more difficult; as it is now more difficult to understand if a verse is beautiful or ugly if heard in the voice of an actor—because the voice of the actor and his performance interfere. Jakobson, once again, I believe, had an actor say the words "good evening" forty times with forty different meanings.5

This does not deny that ORAL poetry has a right to exist, or more precisely, that it exists. Aestheticians have gone mad for years trying to find the difference between the written word of the theatrical text (written and therefore literary) and the spoken word of the performance; as we go crazy today trying to find the difference between the written word of the screenplay and the cinematographic representation. It is only semiology that can resolve these problems, with its descriptions of the different "systems of signs," which in many cases lend themselves to each other to be the most elementary level of "double articulation" (see Umberto Eco).

An objective examination of the system of signs of cinema reveals to us first of all that it is audiovisual: as a historian of religions would say, image and sound are a "biunity." This is a semiological observation; what can an artist do with it? Nothing. It is obviously a completely descriptive observation, applied to that which is. An artist—who may well know nothing of semiology—can instead say to himself, "What a marvelous opportunity! Making my characters speak instead of a naturalistic and purely informative language, only prudently endowed with touches of expressiveness and vivacity—making my characters speak the metalanguage of poetry instead of this language, I would bring oral poetry back to life (which has been lost for centuries, even in the theater) as a new technique, which cannot fail to force us into a series of reflections: (a) on poetry itself, (b) on its destination."

Editor's note: Pier Paolo Pasolini's text "Cinema's Oral Language" was originally published in the Italian journal Cinema Nuovo, no. 201, September-October, 1969. The text was later translated into English and included in Heretical Empiricism, the collection of Pasolini's writings first published by Indiana University Press in 1988 and subsequently republished by New Academia Publishing in 2005.

The film Ugetsu Monogatari (1952) directed by Kenji Mizoguchi. Its subtitle is “tales of the pale August moon” (racconti della luna pallida d’agosto).

Roman Jakobson, "Linguistics and Poetics," in Style in Language, ed. Thomas A. Sebeok (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1960), 367.

See “The Code of Codes,” pp. 276-83, for a discussion of Charles Morris.

Roman Jakobson, "Linguistics and Poetics," in Style in Language, ed. Thomas A. Sebeok (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1960), 354-55.