A dialogue made of gold: such was the conversation between artists Roni Horn and Felix Gonzalez-Torres, initiated in the early 1990s and only interrupted due to Gonzalez-Torres’s death in 1996. It all started on a spring afternoon in 1990, when Gonzalez-Torres, along with his partner Ross Laycock, visited Horn’s solo exhibition (April 22–July 22, 1990) at Temporary Contemporary, the temporary venue of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, and encountered her 1982 work Gold Field.

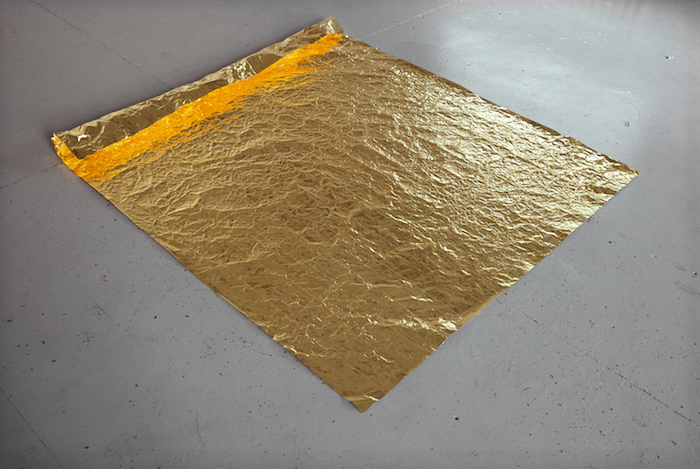

Placed directly on the floor, Gold Field consists of a large and thin rectangular sheet made of one kilo of pure, annealed gold. Gold Field presented itself as “a new landscape, a possible horizon, a place of rest and absolute beauty,”1 giving the couple solace from their dramatic situation: Laycock was dying of AIDS, surviving the show only by six months, and the overall vision of the U.S. as a country that was facing “the abandonment of the ideals on which (it) was supposedly founded” 2 was somber and asphyxiating.

Three years after this encounter with Gold Field, Gonzalez-Torres and Horn meet. Touched by their common affinities, Roni Horn sends Felix Gonzalez-Torres a square of gold foil, a sheet similar to those made by the artist and placed in stacks to be taken by visitors, yet made of gold, a tribute to their newly-born friendship. That same year, Gonzalez-Torres makes "Untitled" (Placebo – Landscape – for Roni) (1993), an endlessly replaceable and forever-lasting golden collection of candies wrapped in golden paper.

Three years later, at the beginning of January 1996, Felix Gonzalez-Torres dies in Miami of AIDS-related complications. The following month, Roni Horn’s solo exhibition “Earths Grow Thick: Works after Emily Dickinson” (February 3–April 21, 1996) opens at the Wexner Centre for the Arts, at Ohio State University, in Columbus, a show that will then be presented at the Davis Museum and Cultural Centre, at Wellesley College, Wellesley (October 22–December 29, 1996) and at the Henry Art Gallery of the University of Washington, Seattle (July 3–September 28, 1997). The exhibition’s catalogue includes “1990: L.A., “The Gold Field”,” a text by Gonzalez-Torres in which absences are deeply felt, as the work was not included in the show, and the author was no longer alive, and which celebrates a friendship that, even when shaped by the artists’ common interest in fragility and delicacy, outlives death.

Every time I read this all-encompassing text I fall victim to a psychoauditory sensation, as if William Basinski’s music were being played around my head. It may be because both text and music are founded on ever-changing repetitions, where the erosion of time affirms itself as being the organic condition for a progressive form of life—as if the awareness of having numbered days were the only formula by which to experience endless love.

Through Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s words, Roni Horn’s Gold Field enters the aforementioned paradigm in the form of a whispered suggestion, an impartial advice. It is not there to distract us from our finite condition, nor to mislead us from the unequal society of our own design. In acting as a reminder, the work points towards the necessity of a better life for as many as possible. In giving a new name to “something that had always been there,”3 it entangles invention with a possible external factual optimization.

Here minimalism stands for honesty: Gold Field seems to acknowledge its own partiality within the daily, perpetuating the notion that the creation of meanings exists only as the outcome of new encounters. The work insinuates that the supremacy of the truths that we’re exposed to will be settled by the people with whom we are going to stress-test the actual truths. From here on the company of the visit to an exhibition becomes more important than the specific exhibition itself.

–Riccardo Benassi

"1990: L.A., 'The Gold Field'” by Felix Gonzalez-Torres

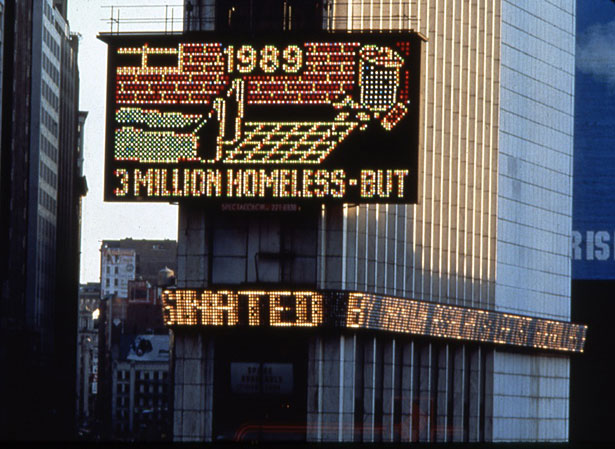

1990: Already ten years into trickle down economics, a rise in cynicism, growing racial and class tension, and the widening gap between the very rich and the rest of us. L.A. before the riots of 1992. A time of defunding vital social programs, the abandonment of the ideals on which our country was supposedly founded. The erasure of history. The Savings and Loan bailout with our tax dollars. “The economic boom" of the Reagan Empire thanks to the tripling of the national deficit. The explosion of the information industry, and at the same time the implosion of meaning. Meaning can only be formulated when we can compare, when we bring information to our daily level, to our “private” sphere. Otherwise information just goes by. Which is precisely what the ideological apparatuses want and need: “You give us 30 minutes and we give you the world." A meaningless one. With internets and highways included. A virtual state of containment. How could the famous "taxpayer" remain idle and voiceless when for every dollar we spent for welfare the government spent six dollars for the Savings and Loan orgy? That was our money that ended up paying for mega takeovers, super mergers, environmentally destructive “developments," and bigger and better (now empty) office spaces. Because it does not mean anything. The American family doesn’t know how to get upset, how to understand a bill of 500 billion dollars. But it can get extremely interested in a 10 thousand dollar grant from the NEA. 500 billion is unthinkable. That amount is not personal. On the other hand, 10 thousand dollars is the down payment for a small home, or a trailer. Now that’s meaning.

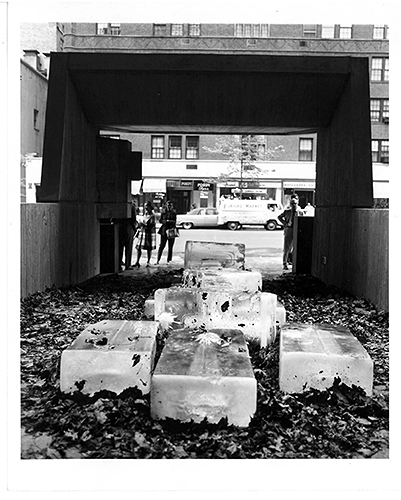

The list of hard data from that fabulous decade was depressing. Especially in the face of public inaction, and the absence of an organized reaction to so many devastating statistics such as the fact that in 1980 the ratio of the U.S. Government budget for housing to military expenditure was 1:5. By 1989 it was 1:31. Since 1980 Federal support for housing assistance has been slashed by more than 80%. According to the Census Bureau, mobile homes were the fastest growing type of dwelling in the 1980s, as the cost of traditional houses soared beyond the reach of many. Nearly 16 million Americans—about one in sixteen—now live in mobile homes. But in a way we built a lot of “safe housing” during that time. According to the September 13, 1992 New York Times, the nation’s incarcerated population increased by nearly 130% over the decade. We have the highest rate of imprisonment of any industrialized nation. During those same years we witnessed the top one percent of American households grow richer. By 1989 that 1% was worth more than the bottom 90%. In those “Dynasty” years the number of children living in poverty increased by 21%. By 1992, 7% of all infants, and nearly 17% of African-American infants were born underweight—the highest rate since 1978. The state with the highest child poverty rate is Mississippi—home of the American Family Association, one of the most vocal organs of the Right Wing Religious Industry.

According to Jennifer Howse, who led the March Dimes Birth Defect Foundation in 1992, the proportion of pregnant women without prenatal care was 25%, the highest in 20 years. We now rank 20th among industrialized nations in preventing infant mortality, and when it comes to immunizing infants against polio, we now rank behind 16 other nations, including Mexico. But who cares. We kicked butt in Grenada. We got more stealth bombers, plans for a real star wars system of toys, and a glamorous, anorexic first lady who exhorted all of us to "just say no." To say no to the formulation of meaning, to concentrate instead on a photograph of two men kissing, or of a crucifix. Symbolism sells. History doesn’t. We must remember that most of the social security net the revisionists wanted to dismantle then (and now) helped cut the poverty rate almost in half, and poverty amongst the elderly by an even greater degree. And we must remember that the war on poverty in the 1960s and 1970s brought many needy Americans medical care, food stamps, prenatal and infant care, legal services, college tuition and guaranteed student loans which enabled many of us to forge a better life. (I can attest to that.) Those programs, according to the New York Times editorial on May 6, 1992, brought the poverty rate down from 19% in 1964 to 11% in 1973.

One of the dangers of the new technologies of information is that they do not guarantee an informed or active public. Sound bytes replace arguments. The statistics on the economic decline of the so-called typical normal American family mean very little to them. One of the effects of the division of labor is the misrepresentation of facts, issues, and events as completely isolated, independent of each other. It does not occur to many that bailing out the white collar crimes of the 1980s means less money for hospitals, repairing roads, and school lunches (remember ketchup as a vegetable?).

And it’s precisely here where the radical right and their allies in the Religious lndustry have been so brilliant in their strategy of deflecting meaning by using charged symbolic images of homosexual acts (among others). Why bother with the destruction of the environment or lack of adequate health care when we have a black and white photo of two men kissing? Now that’s real meaning. Unfortunately, we in the cultural left are more than eager to play the role assigned to us. We are invited to participate in a debate that has never really been a debate, but a travesty, a red herring to keep us occupied. We should not reply with the First Amendment and so-called freedom of expression, we should redirect the circus toward our agenda and expose what they really want to avoid mentioning. We should fight hate and the dissemination of ignorance and fear with the effective use of history and fact. Ideology cannot stand it when we make connections.

L.A. 1990. Yes, it was a very depressing, and very hard to sustain any sense of hope in such a bleak social landscape. How is one supposed to keep any hope alive, the romantic impetus of wishing for a better place as for as many people as possible, the desire for justice, the desire for meaning, and history?

L.A. 1990. Ross and I spent every Saturday afternoon visiting galleries, museums, thrift shops, and going on long, very long drives all around L.A., enjoying the “magic hour” when the light makes everything gold and magical in that city. It was the best and worst of times. Ross was dying right in front of my eyes. Leaving me. It was the first time in my life when I knew for sure where the money for rent was coming from. It was a time of desperation, yet of growth too.

1990, L.A. The Gold Field. How can I deal with the Gold Field? I don’t quite know. But the Gold Field was there. Ross and I entered the Museum of Contemporary Art, and without knowing the work of Roni Horn we were blown away by the heroic, gentle and horizontal presence of this gift. There it was, in a white room, all by itself, it didn’t need company, it didn’t need anything. Sitting on the floor, ever so lightly. A new landscape, a possible horizon, a place of rest and absolute beauty. Waiting for the right viewer willing and needing to be moved to a place of the imagination. This piece is nothing more than a thin layer of gold. It is everything a good poem by Wallace Stevens is; precise, with no extra baggage, nothing extra. A poem that feels secure and dares to unravel itself, to become naked, to be enjoyed in a tactile manner, but beyond that, in an intellectual way too. Ross and I were lifted. That gesture was all we needed to rest, to think about the possibility of change. This showed the innate ability of an artist proposing to make this place a better place. How truly revolutionary.

This work was needed. This was an undiscovered ocean for us. It was impossible, yet it was real, we saw this landscape. Like no other landscape. We felt it. We traveled together to countless sunsets. But where did this object come from? Who produced this piece that risked itself by being so fragile, just laying on the floor, no base, no plexiglass box on top of it. How come we didn’t know about her work before, how come we missed so much? Roni’s work has never been the darling of the establishment. Of course not. Some people dismiss Roni’s work as pure formalism, as if such purity were possible after years of knowing that the act of looking at an object, any object, is transfigured by gender, race, socio-economic class, and sexual orientation. We cannot blame them for the emptiness in which they live, for they cannot see the almost perfect emotions and solutions her objects and writings give us. A place to dream, to regain energy, to dare. Ross and I always talked about this work, how much it affected us. After that any sunset became “The Gold Field." Roni had named something that had always been there. Now we saw it through her eyes, her imagination.

In the midst of our private disaster of Ross’s imminent death, and the darkness of that particular historical moment, we were given the chance to ponder on the opportunity to regain our breath, and breathe a romantic air only true lovers breathe.

Recently Roni revisited the Gold FieId. This time it is two sheets. Two, a number of companionship, of doubled pleasure, a pair, a couple, one on top of the other. Mirroring and emanating light. When Roni showed me this new work she said “there is sweat in-between." I knew that.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “1990: L.A., “The Gold Field” first appeared in the catalogue Roni Horn. Earths Grow Thick (Columbus: Wexner Center for the Arts, 1996). The text is reprinted with the kind permission of Roni Horn, the Wexner Centre for the Arts, and The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “1990: L.A., “The Gold Field”,” in Roni Horn. Earths Grow Thick (Columbus: Wexner Center for the Arts Publication, 1996), 68.

Ibid, 65.

Ibid, 69.