The big social groups (consisting of classes, parts of classes, or institutions … ) act with and/or against each other. From their interactions, strategies, successes, and defeats grow the qualities and “properties” of urban space.

—Henri Lefèbvre

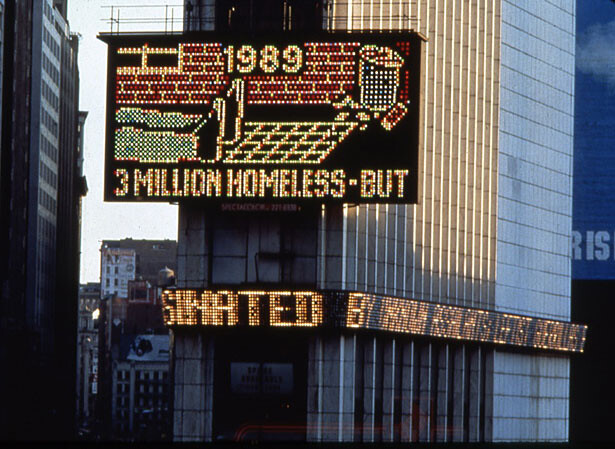

(Under)Privileged Urban Spaces

By the end of the 1980s, during the period in which Martha Rosler was realizing her three-part exhibition and action project If You Lived Here…, New York was frequently described as the city where social distinctions and disintegration were the most blatantly visible, a “localized unity of the sharpest contradictions,” a “city of contradictions, of rich and poor, of glitz and gloom.”1 The homeless here represented the tip of the iceberg of unbalanced state and urban social policies, the “principal conservative government objective being to make these people invisible, to get them out of the way, to neutralize them.”2 In 1990 there were 70,000–80,000 homeless in New York and 250,000 who were at risk of losing their homes.3 The drastic cuts in social spending, together with the increasing rate of inflation due to the worldwide financial crisis at the end of the 1980s and the cutbacks in jobs, entailed a rapid pauperization among the middle and lower classes. Additional cuts in state subsidies for affordable housing further exacerbated the housing situation:

The Reagan Administration slashed low-income housing funds steadily (from $32 billion to $7 billion) while inflation rose, the minimum wage stagnated, deindustrialization threw tens of thousands out of work, and social “entitlement” programs were cut.4

The (in)visibility of the socially underprivileged and the properties of the urban spaces they inhabit formed the starting point for the If You Lived Here…project, a concrete and participatory realization of Rosler’s thinking on the topic.

One of the artist’s first concerns in the project was to revise the definition of homelessness as restricted to those visible on the streets. For it is not only these people who are homeless, so are all those living in “shelters” or staying with relatives or friends. A more rigorous definition would embrace all those who have no private living space, in other words no sphere of privacy, such that they are in a constant state of jeopardy. Pierre Bourdieu describes a person’s existential relation to their position in terms of the social status conferred by the appropriation/possession of a particular extent of physical space:

Each agent may be characterized by the place where he or she is situated more or less permanently, that is, by her place of residence (those who are “without hearth or home,” without “permanent residence” … have almost no social existence—see the political status of the homeless) … It is also characterized by the place it legally occupies in space through properties (houses and apartments or offices, land for cultivation or residential development, etc.) which are more or less congesting … . It follows that the locus and the place occupied by an agent in appropriated social space are excellent indicators of his or her position in social space.5

In this way, human existence can be considered spatially. “Space” here is an indicator of the power accessible to a privileged social group, to be obtained and defended on the principle that it is simultaneously withheld from other groups. Less privileged, marginal social groups take up the spaces and enclaves assigned to them, or, like the homeless, have vagabond status.6 Hence the “homeless and other benefit-dependent groups … have no part at all in the struggles for territory. The absence of their own defined and hence defense-worthy space of collective consumption mirrors their lack of social cohesion.”6 Rosler’s strategy in If You Lived Here… becomes operative at precisely this point.

Because action and not representation is central, and because participation is an essential part of If You Lived Here…, Rosler succeeds in granting the homeless concerned, and their overall situation, a power to act that has its roots in the correlation of space and power.

This spatial aspect of Rosler’s works is almost always developed in immediate relation to her life in the city and her observation of media and urban processes.7 The following factors played a role vis-à-vis the original location of the If You Lived Here… exhibition at Dia Center for the Arts, then in New York’s SoHo district: the sociopolitical mechanisms regulating the housing market and the distribution of subsidies among classes of the population at the national level and at the communal level in New York; the impact of the flourishing art market in the 1980s on the art “scene” in SoHo; the Dia Art Foundation’s own profile and activities; the state and appearance of its spaces as well as their location in the city of New York and/or in the district of SoHo, and the history of how they were originally used and why they were reorganized and put to new use.

The Institution: Dia Center for the Arts

Deriving from the Greek prefix meaning “through” or “across,” the name “Dia” points to the founders’ aim to establish an organization that would transgress boundaries, or, in the words of Charles Wright, its director at the time, “to suggest our role as the conduit or means for realizing … extraordinary projects.”8 But was Dia genuinely transgressive? Until then it had mainly supported large-scale projects by exclusively white male artists involving high financial and material outlays, thus echoing the prevailing politics of mainline “operating system” U.S. art. Yet Dia cannot just be reduced to an “esoteric patron of big and extravagant projects.”9 The transgressiveness of Dia’s activities lies less in its exhibitions of visual art than in the events, facilities, and publications surrounding them: a young dance and literature program, symposia and panel talks on contemporary art and social issues with artists and specialists from various disciplines, as well as their own series of publications (in which Rosler’s book was the seventh volume), hosting the bookshop Printed Matter, and so on. Around this time, the dancer and filmmaker Yvonne Rainer, who was a member of Dia’s advisory board, pointed to the need to present artists whose social strategies could be expected to go beyond the customary limits of exhibiting institutions. Shortly after, Rosler and the artist collective Group Material were each invited to mount a six-month exhibition project in Dia’s space on Wooster Street.10

Rosler’s If You Lived Here… and Group Material’s project Democracy consisted of several thematically related exhibition sequences and discussion rounds. Rosler’s exhibitions were provisional in their appearance—unpretentious and almost disorderly, containing relevant informational material from art and non-art sources in a wide range of media. It is important to view the exhibitions and exhibition formats, as well as their programming, as a whole. Rosler developed an exhibition style in which types of work, materials, and media that otherwise had nothing to do with art played a clear role in relation to her subject matter. And the exhibition projects were at their most transgressive when she and Group Material worked both within and against the limits of traditional institutions. Furthermore, by provoking situations that put the institution’s original liberal intentions to the test, Rosler’s project also formulated an inherent critique of the hosting institution.

If You Lived Here…(1989)

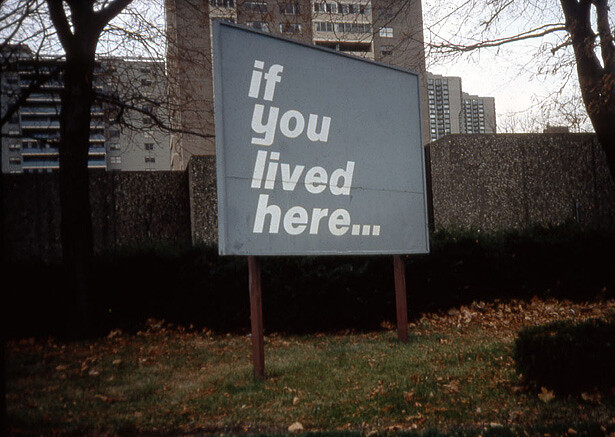

The title “If You Lived Here…” is borrowed from an advertising slogan. It was part of a real estate agent’s poster text attempting to pitch downtown residences to middle-class suburban commuters with the message: “If you lived here, you’d be home now.”11 In the context of the exhibitions, the slogan reads, on the one hand, as an appeal for the strategic conversion of the art institution into a living space; but it also points to the role of the Dia Art Foundation—and of galleries and art spaces in general—as driving forces in the gentrification of city districts that leads to the rising rents that force longtime residents to move away, or, in the worst cases leave them homeless.

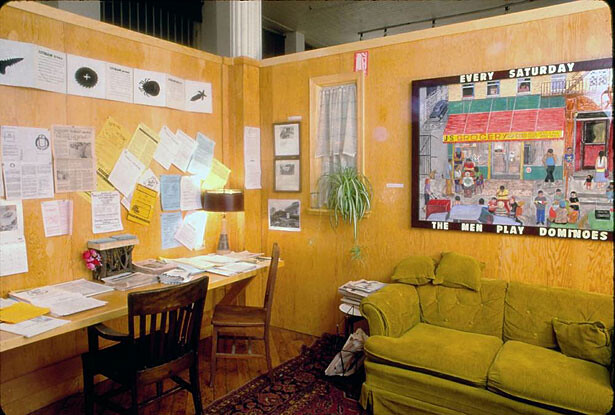

In the context of the project, the slogan “Come on in we’re home” that adorned the entrance in red letters equated the art institution with home. The project had three parts involving over two hundred artists and activists invited by Rosler: “Home Front” focused on different forms of self-organized activism such as rent strikes or self-governing housing projects; “Homeless: The Street and Other Venues” addressed the visible and invisible homelessness of streets and metro stations, but also that of public housing and casual accommodation with friends and relatives; and, finally, “City: Visions and Revisions” aimed at developing, with the aid of architects and planning groups behind initiatives for the homeless, alternative urban planning strategies.12 Each exhibition had its motto on the wall opposite the entrance. The motto in “Home Front” was a dictum uttered by mayor Ed Koch: “If you can’t afford to live here, mo-o-ove!!”—the principle of gentrification in a nutshell. The topic of gentrification was present in many contributions to the exhibition, both in the form of documentation and activist presentations. The words of a Long Beach City Council member (planning to restructure Long Beach for the construction of a gigantic shopping mall in 1979) used by Allan Sekula for the title of a work came surprisingly close to the exhibition motto: “People who can’t afford to live here should move someplace else.” The main part of the exhibition consisted of a documentary exploration of housing politics that, for the most part, affected the artists and self-organized groups involved. Rosler’s apt definition of the options and restrictions of documentary art practice lay at the heart of the project: “Documentary practices are social practices, producing meanings within specific contexts…. An underlying strategy of the project If You Lived Here… has therefore been to use and extend documentary strategies.”13

In this sense, the “Clinton Coalition of Concern”—an action group founded as a means of intervening directly in the Manhattan district known as “Clinton” or “Hell’s Kitchen”—took the case study of a building to document the process of “warehousing,” using documents, letters, and photos to expose the clandestine measures used by landlords to circumvent the law.14 Willie Birch’s gouache Every Saturday the Men Play Dominoes (1987), on the other hand, depicts a street scene outside a grocery store. By not appealing to any pre-established standards in the art scene (in which she herself asserts a position) in her selection of these works, it is clear that the overall conceptual context of the project is less focused on setting a new standard than on subverting the aesthetic conventions of the art market as a whole.

A quotation from Peter Marcuse, an active urban planner and professor at Columbia University at the time, provided the motto for the second part of the project (“Homeless: The Street and Other Venues”): “Homelessness exists not because the housing system is not working, but because this is the way it works.” Thus Marcuse places the political convenience of homelessness into question.

While, with occasional exceptions, the theoretical causes of homelessness were addressed by discursive events in this part of the project, the artists themselves tended to explore homeless life as such, concerned with means of both help and self-help. Krzysztof Wodiczko, in his “Homeless Vehicle Project” (1988), and the architect group Mad Housers from Atlanta, each developed models of provisional accommodation geared to minimal space requirements for sleeping and storage. Wodiczko emphasized the aspect of vagabondage and nomadic existence, while the Mad Housers’ provisional models projected a temporary stability for homeless life on the streets of the metropolis. After being dismantled in May of 1989, one of the huts that was part of the Mad Housers’ contribution to the show was re-erected in a vacant construction lot. Two further huts were put up in Brooklyn and Manhattan while the exhibition was running, and were used by homeless people.

The Homeward Bound Community Service, a self-organized homeless group whose most effective project involved registering 5,000 homeless people to vote, itself operates from no fixed address. The group used the exhibition as a temporary abode, fitting out an office in the rooms of the Dia Foundation. The activists even produced a “professional” letterhead for their temporary location—apart from the organizational benefits of having an address, it also symbolized a certain social status.

The need to present the complexity of homelessness and dismantle the cliché of a homogeneous social group came out clearly in the exhibition and surrounding discussions: the common denominator that united a wide range of people with varying needs was a simple matter of the absence of a place to live. This is why different self-help organizations such as Teens on the Move, Parents on the Move, and Caucus to House People With AIDS sprang up to address a particular problem area by offering essential help to homeless teenagers, families, AIDS victims, alcoholics, drug addicts, and so on; or by simply registering homeless people to exercise their right as citizens to vote, as the Homeward Bound Community Service did.

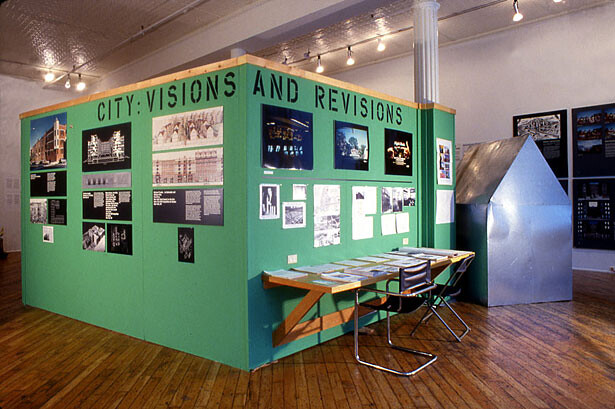

The last part of the project, “City: Visions and Revisions,” analyzed, discussed, and criticized existing urban structures, architecture, and urban planning, and focused on improving living conditions in the city. Ideas for buildings suitable to certain social groups threatened with homelessness, or for those with special housing needs were considered alongside ways through which these housing projects could be integrated into the broader urban context. Consequently, the participants were in large part artists, architects, and activists who explored specific architectural or urban planning scenarios through a documentary approach or presented architectural plans for improving the social conditions of a particular district. The exhibition motto, “Under the Cobblestones, the Beach,” adopted a phrase coined during the Paris student revolts of 1968. Many of the exhibition contributions concerned SoHo, Manhattan, and other regions of New York City. There were also projects from other cities detailing similar urban processes were also involved, such as Docklands Community Poster Projects from London, referring to the London docklands development that was frequently compared to Battery Park City during its planning phase.

Dan Graham and Robin Hurst’s exhibition contribution viewed the design and function of downtown plazas or “corporate atriums” ironically as “urban arcadias.” In their photo and text work “‘Private’ Public Space: The Corporate Atrium Garden” (1987) they compare several plazas in New York City with the roofing constructed over the entrance of the Hyatt Regency Hotel in San Antonio, Texas’ River Walk. While a zoning law established at the end of the 1960s prompted a rapid increase in available plots of rentable land as well as plaza construction favoring this particular type of construction plan, the centralization that began in the late 1970s also stimulated the need for green and quiet in city centers, as the upper middle class began moving in from the suburbs. Graham and Hurst see the plazas as “accommodating” this trend. The need for nature is satisfied with a surrogate version of it under protective glass roofing to render the commute between suburban domicile and downtown workplace superfluous.

Other projects in the exhibition endeavored to take certain communities with joint interests into account. For instance, a group of architects presented “Homes for People with AIDS” (1988), a housing plan developed according to the specific requirements of AIDS patients.15 The photographic exhibition “Ruins and Revival” (1983) by Kenneth Jackson and Camilo Vergara documented the decay and reconstruction of buildings in the South Bronx and other areas of New York City.16

Structure and Course of the Project

The interconnectedness of the three exhibitions came out in the structuring of their events through parallel courses. The extremely well-attended “Open Forums” discussions on the various subjects tackled in the project were a major component of each exhibition. Talks and their ensuing discussions shed light not only on the work of activist organizations and the role they envision for themselves, but also on the political backdrop to homelessness. For instance, parallel to the first exhibition, the open forum “Home Front” addressed the subject of “Housing: Gentrification, Dislocation, and Fighting Back.”17 The second discussion round addressed “Homelessness: Conditions, Causes and Cures.”18 Finally, the open forum accompanying “City: Visions and Revisions” examined politics and industry in relation to the housing market in light of research and case studies.19

A further forum titled “Artists’ Life/Work: Housing and Community for Artists” addressed artists and their particular housing situation, discussing the instrumentalization of artists in the process of gentrification. As Yvonne Rainer expressed: “We are the avant-garde of gentrification, or on the other hand, we are scavengers.”20

Each of the exhibitions included a substantial video presentation and a reading room structured differently for each show. The reading room on the subject of “Homelessness: Conditions, Causes and Cures,” for instance, was designed after an asylum-seekers’ home, with six simple beds placed in a row covered with woolen blankets serving as seats. Arranged this way, the view into the exhibition space gave the impression of a substandard living room.

Compared to conventional exhibitions, a striking variety of media were on display: installations, photographic works, pictures on canvas, posters, documentations, manifestos, photocopies, and prints. The formal heterogeneity was matched by the choice to exhibit established artists such as Krzysztof Wodiczko, Dan Graham, Max Becher, and Allan Sekula alongside less familiar and in part homeless artists promoting squatter initiatives and activist groups. This compelled visitors whose expectations had been shaped by the conventional image of an institutional exhibition to reconsider traditional definitions and categories of the “work of art” and its presentation. Rosler herself stressed three communicative layers in particular: “First there were works of art and installations by individual artists or groups, some of which included texts. Then, along the upper parts of the walls, lost space in modern art rooms, there were enlargements of real estate advertisements together with graphs and statistics on housing policies in the USA and New York City. Finally, there was printed reading matter in different forms.”21

Institutional Space and Urban Space

“We must confront the social space in which homelessness occurs—the city.”22 Thus, Rosler describes her standpoint regarding the problem of homelessness. However, one does not experience the city, considered as a social space, as homogenous—rather, it exhibits boundaries that are socially and politically sanctioned. Rosler’s project provokes the crossing of such boundaries by bringing together socially distinct areas: artist / exhibition maker, art-world artist / counterculture artist, interior / exterior, exhibiting institution / urban space, documentation / activism.

Rosler’s selection of the participating artists, activists, and theorists was carefully calculated to give them access to an established art institution and forum outside their respective fields. If You Lived Here… was a non-hierarchical collaboration of unknown homeless artists, well-known artists, and others supporting homeless initiatives invited to perform activist work within—and aided by—the art institution. Local networks come into contact with larger ones and introduce their activities to a new, broader, heterogeneous public. As a privileged individual, Rosler uses and diverts the art institution’s power in the name of an invited artist, while at the same time divesting herself of autonomous authorship. She works with and on the exhibition space and its position—in the city, in the art scene, and with the attendant public. Hence Rosler aligns the mainstream art system with a sociopolitical activism related to no institution—one which is in fact constitutionally anti-institutional.

The “artist as social worker,” however, is a dubious concept for art criticism. The mainstream art system always plays a role, and is even actively reflected by Rosler’s work. Likewise, the results and effects of her work—not to mention its objectives and strategy—differ greatly from those sought by a social worker. While the project involves political intervention, it cannot be considered apart from its intervention in the art system, and this yoking of activism and institutional critique is a constitutive and seminal feature of Rosler’s work.

The public at the openings and discussion events was a blend of activists and the usual art public. While this was Rosler’s intention, it cannot be said to have always been successful. The art public did not take an active role in the discussions, and though numerous art critics were present, hardly a single American art journal reviewed the project, which was highly unusual for a Dia event of this scope. European publications, on the other hand, retrospectively cited Rosler’s project as a consistent and minutely planned implementation of integrative strategies.23 The irony that a locally concerned project should be ignored locally and attract attention on the international art scene points directly to the art world’s inability to integrate political projects involving “community” participation. It is precisely this inflexibility that was largely responsible for the disappearance of such art practices in the 1990s.

While the SoHo art public may not have been keen to make their voices heard, the active and passive participation of the homeless involved in the project was prefaced by their temporarily leaving their usual districts and positions in social space. An assumption that this social space likewise constitutes a place within a hierarchical social order is concisely expressed by Bourdieu’s definition of “habitus” as a synthesis of a person’s social position and lifestyle.24 Within the institutionalized terrain of art, Rosler staged a temporary experimental format that called on people to step outside of such a “habitus,” raising the broader question of whether a person whose position is defined by homelessness actually has the ability to step outside of their place in the social order. With If You Lived Here…, Rosler used institutional space to delineate a porous sphere within the system of social spaces, diverting the white cube’s auratic, aesthetic, elitist, and exclusive properties into a social space for communication and information.

Between “Alternative Space” and “New Institutionalism”

In If You Lived Here…, Rosler, who avoided the title of curator, tied the locally oriented, deliberately “deprofessionalized” practice of self-organized alternative spaces of the late 1960s and 1970s together with curatorial approaches that were to be later considered within the scope of “new institutionalism.”25 Her tension-packed project in an established institution and her choice of formats anticipated curatorial approaches that would only later become broader curatorial practices. While those who ran alternative spaces deliberately shunned exhibiting in institutions and galleries, positioning themselves as an alternative on the periphery of the art world, new institutionalism builds on an internalized critique within the institutions themselves. This critique is no longer seen as an—albeit ultimately “desirable”—activity conducted solely by artists against an institution (and limited to the exhibition format), but is instead deployed at the level of institutional administration and programming by curators themselves, who initiate a drive for critique and structural change together with artists.26

In considering the processual structure of If You Lived Here… alongside its open forums, reading rooms, publication conceived as both component and further platform for the project (and not just as a catalogue or documentation), its multipart, thematically focused exhibitions, its local participation going beyond the art public, the collaboration of architects and theorists from other disciplines, as well as the artist’s dissolution of her authorship and the inclusion of the public in communicative processes—one discovers the very elements and intentions with which curators strove to restructure institutions around 2000. Here, one might cite the Rooseum in Malmö under Charles Esche, or the Kunstverein in Munich under Maria Lind’s directorship. While in order to realize this multi-layered project, Rosler had to hijack an institution as an artist playing the role of a freelance curator, the approaches twenty years later are now institutionally legitimized through collaborations between an institutional agent, the curator, and artists.

But Rosler’s spatial strategies also call to mind art strategies that produce social space—whether for direct social interaction, as with Rirkrit Tiravanija—or abstract social spaces (such as cultural space), as with Fred Wilson or the early work of Renée Green. While Rosler uses the urban as her guide for deliberately integrating specific groups of people, with Rirkrit Tiravanija the fundamental space-building event is considered to be a matter of recipients’ participation in the artistic process, and not in terms of their politicized living conditions. Instead, people come together from various sectors of the regular art public, communicating and consuming within the dispositive strategies staged by Tiravanija. The cultural space contextualized by Green in her early works, on the other hand, emerges in relation to trans-cultural constellations present at the exhibition venue. Works such as “Import/Export Funk Office” (1992–1994) were recontextualized with respect to the specific institutions and cities that hosted the work. The model of the white cube as “work station” with successive chains of local activities (as Green established) posits a transnational nomadism to be considered against the backdrop of postcolonial, diasporic identities.

Taking these developments into account, Rosler’s If You Lived Here… not only draws the direct politicization of the 1970s together with the more hermetic politics of new institutionalism, but also stands at the dawn of artistic exploration concerned with the production of concrete and abstract social spaces that emerged in the 1990s.

Hartmut Häußermann and Walter Siebel, “Lernen von New York?,” in NewYork: Strukturen einer Metropole, ed. Häußermann and Siebel(Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1993), 21; Adrienne Windhoff-Héritier, “Das Dilemma der Städte: Sozialpolitik in New York City,” in Häußermann and Siebel, New York:Strukturen einer Metropole, 239.

Peter Marcuse, “Wohnen in New York: Segregationund fortgeschrittene Obdachlosigkeit in einer viergeteilten Stadt,” in Häußermann and Siebel, New York:Strukturen einer Metropole, 226. See also: “Homelessness today [is] somethingnew, something that one could call ‘advanced homelessness’ and which occurs asthe logical concomitant of a whole range of economic and political changes … : homelessness in a technologically developed society,homelessness amid wealth and affluence,” 205.

Statistics of the “InterfaithAssembly on Homelessness and Housing’” (1990), cited in If You Lived Here: The City in Art, Theory, and Social Activism: AProject by Martha Rosler, ed. Brian Wallis(Seattle: The New Press, 1991), 207.

If You Lived Here…, press release.

Pierre Bourdieu,“Physical Space, Social Space and Habitus,” Rapport (Department of Sociology andHuman Geography, University of Oslo) 10 (1996): 11.

Michael Dear and Jennifer Wolch, “Wiedas Territorium gesellschaftliche Zusammenhänge strukturiert,” in Stadt-Räume, ed. MartinWentz (Frankfurt am Main: Campus 1991), 246. Since 1960 Kevin Lynch has beenusing cognitive mapping as a research method to show the variable access ofdifferent groups to the city in which they live. Maps drawn from memory reflecthow different people perceive distances differently, or even the very existenceof city districts, depending on whether or not certain areas are frequented bya given social, ethnic, etc., group. Intentional omissions can occur (in thecase of socially higher-placed groups), and prohibited access can be subtlyindicated (with regard to underprivileged groups).

Rosler refused to makeuse of objects from the New York exhibition for an exhibition in St. Louis in1992: “And I told them this doesn’t interest me, because this has nothing to dowith the local community. So I stayed in St. Louis for a couple of weeks. Iwent to a lot of different sites and asked people if they would be interestedin working with me. There are no organized groups of homeless people, St. Louisis in the south of the United States and things are really different there.” Rosler inconversation with the author, Berlin, September 15, 1996.

Charles Wright, Director’s Report 1993–94, 2.

Jochen Becker, “L’art pourl’institution,” Kunstforum international 125 (January/February 1994): 227.

The DiaArt Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the New York StateCouncil of the Arts were sponsors for both of the projects.

“I called my project ‘If You LivedHere…,’ from the memory of a gigantic sign Iused to see in childhood … . In 1989 I chose this slogan for the showsbecause it is a real-estate line, one I had subsequently seen repeatedelsewhere …” Martha Rosler, in Place, Position, Presentation, Public,ed. Ine Gevers (Amsterdam:Jan van Eyck Akademie/Maastricht, 1993), 82.

February 11–March 18, April1–19, and May 13–June 17, 1989, respectively.

Martha Rosler,in Wallis, If You Lived Here…, 33.

The areaextending west of Times Square is referred to primarily by real-estate agents as “Clinton”after a corporation that invested there. Otherwise the name “Hell’s Kitchen” iswidespread.

Linda Baldwin, Gustavo Bonevardi, Morgan Hare, and Lee Ledbetter.

Previously shown at the BronxInstitute, Herbert H. Lehmann College, and at the City University of New York.

The speakers were Irma Rodriguez,Chairwoman of the “Task Force on Housing Court,” a legal counseling andplacement organization for tenants; Neil Smith, Professor of Geography atRutgers University; Jim Haughton, representing several activist tenantorganizations; Oda Friedheimof the “Housing Justice Campaign”; the filmmaker BienvenidaMatias, who participated in the exhibition; andLori-Jean Saigh, the performance artist in the“Clinton Coalition of Concern.” The panel criticized mayor Edward Koch at thecommunal level as well as Reagan’s political decisions and their consequencesfor the United States. Smith introduced the image of the “frontier” into thediscussion connected with gentrification in Manhattan. During the unrestbetween police and demonstrating gentrification victims in the Tompkins Squarearea of the Lower East Side on August 6, 1988, Koch spoke of “frontierviolence”—a formulation testifying to what he saw as border struggles andterritorial claims. Smith quotes Koch in Wallis, If You Lived Here…,108.

The participants in this second legof the project were mainly members of activist aid and self-aid groups,self-organized accommodation, workshop, and political action groups.

The panel consisted of theorists andplanners: Robert Friedman of New York Newsday; the artist JamelieHassan; Peter Marcuse, urban planner at Columbia University; Mary Ellen Phifer, Chairwoman of the “Association of CommunityOrganizations for Reform Now” (Acorn), which organizes the reconstruction ofderelict and uninhabited buildings by and for the homeless; the politicalscientist Frances Fox Piven; and Peter Wood, Directorof the “Mutual Housing Association of New York” (MHANY).

Yvonne Rainer, in Wallis, If You Lived Here…, 169.

Martha Rosler,“If You Lived Here…,” in Copyshop, Kunstpraxis & PolitischeÖffentlichkeit, ed. BüroBert (Berlin: Edition ID-Archiv, 1993), 73.

Martha Rosler,“Fragments of a Metropolitan Viewpoint,” in Wallis, If You Lived Here…,15.

See for example BüroBert, Copyshop, Kunstpraxis& Politische Öffentlichkeit,73–76.

“The habituscould be considered as a subjective but not individual system of internalizedstructures, schemes of perception, conception, and action common to all membersof the same group or class.” Pierre Bourdieu, Outline of a Theory of Practice, trans.Richard Nice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977), 86.

See for example ed. Jonas Ekeberg, NewInstitutionalism, Office for Contemporary Art Norway, 2003.

See also my text “The Rise and Fallof New Institutionalism,” Transform, August 2007, →.

Category

Translated from the German by Christopher Jenkin-Jones