September 13–October 27, 2013

There are always good reasons to organize a General Idea exhibition—not because of new work or freshly discovered findings, but because the artistic collective’s only surviving member AA Bronson has cultivated an afterlife of General Idea that persists into the present day. First initiated in 1969, its central members AA Bronson, Felix Partz, and Jorge Zontal officially disbanded in 1994 when Partz and Zontal passed away. Over more than twenty years of collaboration, General Idea produced a unique artistic horizon that fundamentally questioned not only the social dignity of art, but also social systems of value and morality in general, using whatever medium necessary to create their art as an all-encompassing yet serious practical joke. It is within this horizon that Bronson has preserved its legacy since the mid-1990s, ingeniously demonstrating the continued relevance of General Idea. And today—as we face a perennial crisis, one that has taken hold of Europe as much as the United States for the past five years, and are witnessing the breakdown of traditional models of social and economic self-evidences—it is thus again the perfect time for some General Idea (GI).

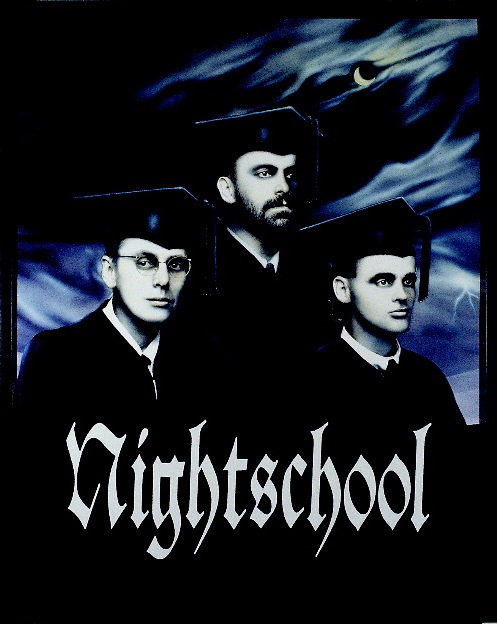

The title of the exhibition is taken from one of GI’s more enigmatic and much reproduced works P is for Poodle (1982–89), a self-portrait of its three core members dressed as poodles in suits. Since the mid-1980s, these group self-portraits—which present the artists as a shared identity and are part of their ongoing “Three Men Series”—have played a central role in their artistic practice, and four of them serve to frame the Zürich show. In Nightschool (1989), the artists assume the guise of college graduates with white shirts, gowns, ties, and mortarboards in an airbrushed, moonlit setting. Although the triangular composition remains the same, with Partz facing the viewer, the arrangement of the artists in Playing Doctor (1992) is reversed: Zontal is placed in the center of the image slightly elevated above Partz and Bronson. Wearing doctor’s lab coats, they use their colored stethoscopes on one another as they fade into a background of floating pills. In this sense, the “Three Men Series” is a work in constant transformation, whereby self-representation acquires a monumental status and is subject to continuous revitalization. The last image of the series is entitled Fin de Siècle (1994), and what we see are not Bronson, Partz, and Zontal, but instead the kitschy illustration of three white seal pups lounging in a light blue landscape of ice, reminiscent of Caspar David Friedrich’s Sea of Ice (1823/24). These last two portraits are representative of what Bronson has subsequently identified as the group’s “AIDS era,” which marked their critical engagement with the AIDS crisis, as well as the ultimate loss of Partz and Zontal to the disease.

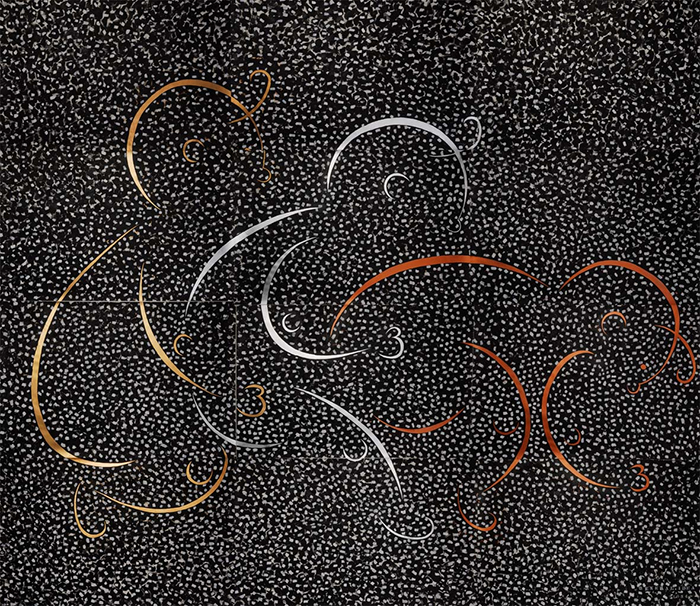

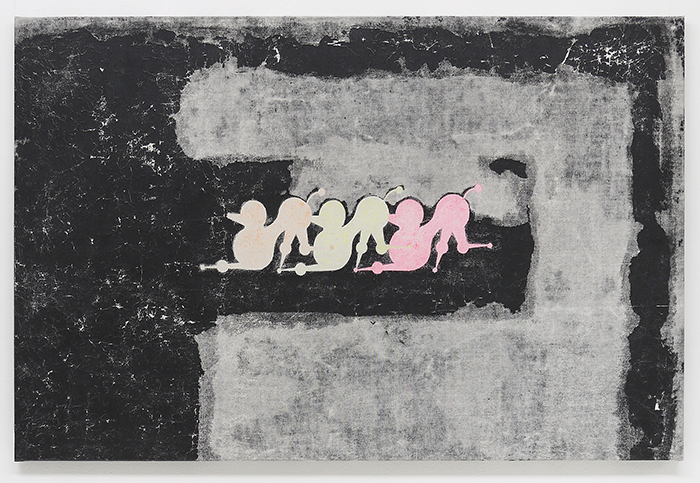

This shifting, but always over-stylized, self-representation is characteristic of much of GI’s work. Resulting in the deliberate banalization of cultural heritage and its historicized forms of cultural distinction, they readily appropriate pre-existing objects and icons and make them their own. The exhibition captures this idea perfectly by showcasing these group self-portraits, alongside earlier work all accompanied by their paradigmatic emblem, the poodle. In the three examples from the sexualized “Baby Paintings Series,” which began in 1984—as well as in the painting featuring three poodles, Mondo Cane Kama Sutra (Distressed) #16 (1983/1988)—schematic figures of a ménage à trois are rendered in custom-made variations on a singular graphic identity. The pieces are executed on silk, masonite, paper, and canvas, and ennobled with the use of pseudo-historic materials, like gold leaf and enamel. Again, trivialization and elevation are closely knit together, and they give way to the archaeology of another civilization, that of GI. This self-archaeologization is what guided GI’s persistent invention of new artistic formats, ranging from FILE magazine (1972–1989), to countless emblems and scores, to The Miss General Idea Pageant (1971), an event which mimicked the beauty pageants of its time, crowning a Miss General Idea in an absurdist, yet fully fledged public ceremony. In 1981, the group excavated archeological fragments of the Miss General Idea Pavilion of 1984 because—as Partz put it—they were “trying to create a work that is perfect for the museum/gallery context, something that requires conservation and delicate handling.”

At Mai 36 Galerie, those archeological findings—colored plaster casts of poodle reliefs and artifacts from the group’s literally pre-historic pavilion—are shown in eight large vitrines. They serve as the monumental centerpiece of the exhibition. Presented in the style of an archeological museum, an army of tiny poodles have been preciously laid out on beige linen. This was a signature, which—as the art historian Stephan Trescher has noted—GI appropriated from the Surrealist illustrator Valentine Hugo. Here, the poodle is transformed into a Pompeii-style archeological witness, testifying to the construction of GI’s ancient significance, and to the fact that the rich cultural history they invented has never been exhausted, and will always be ahead of itself. In the back room of the gallery, one finds a large-scale GI copy of Hugo’s poodle design, assuming the form of an immense panel painting. Drawn with pink acrylic paint on cheap, but gold-coated wooden panels, it even bears the original title of Hugo’s work, La Caniche à la Mode. It was 1945 when Hugo first completed this design. GI appropriated it nearly half a century later, between 1981 and 1991, and since then it has been living on as the marker of a discrete cultural history, that of a general idea. Today, the future seems to be in crisis, and the past re-emerges amongst the present tense, calling for cultural values to be resurrected. GI demonstrates how such temporal inversions can be a source of limitless and ongoing self-invention instead of conservative nostalgia.