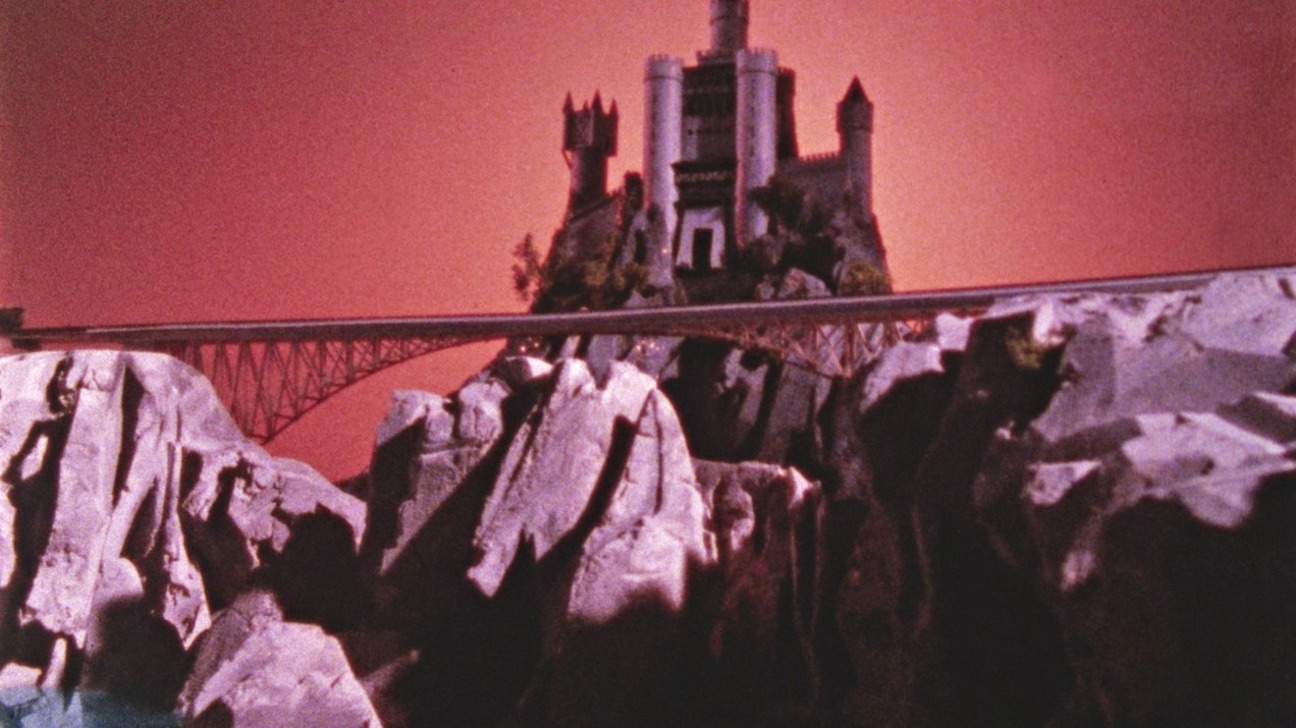

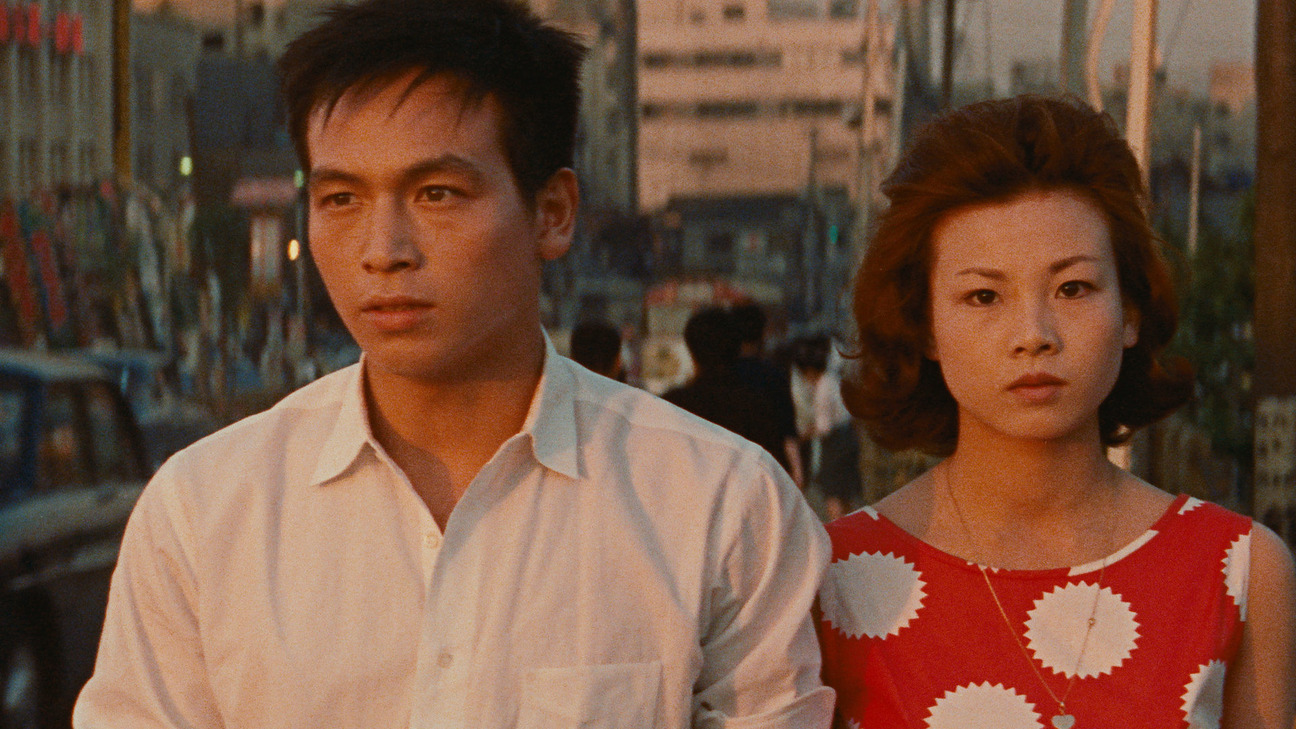

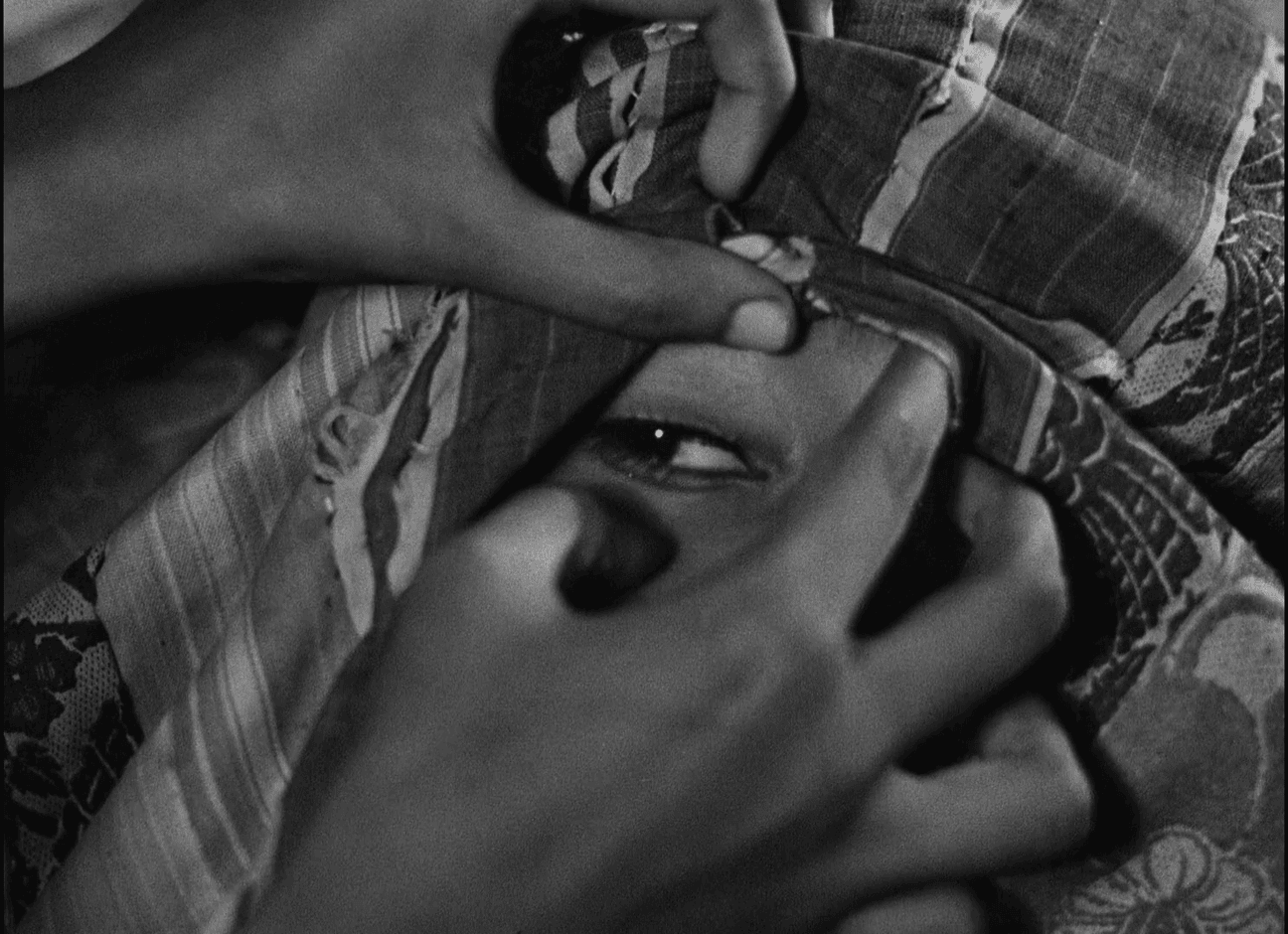

Sarah Maldoror, Sambizanga (still), 1972.

I am one of those modern women who try to combine work and family life, and just like it is for all the others, it’s a problem for me. Children need a home and a mother.1 That’s why I try to prepare and edit my films in Paris during the long summer vacation when the children are free and can come along. . . My situation is a very difficult one. I make films about liberation movements. But, the money for such film production is to be found not in Africa, but in Europe. For that reason, I have to live where the money is to be raised, and then do my work in Africa.

To begin, Sambizanga is a story taken from reality: a liberation fighter, one of the many, dies from severe torture. But my chief concern with this film was to make Europeans, who hardly know anything about Africa, conscious of the forgotten war in Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau. And when I address myself to Europeans that is because it is the French distribution companies who determine whether the people in Africa will get to see a certain film or not. After twelve years of independence, it is your companies—UGC, Nef, Glaude Nedjar, and Vincent Malle—who hold in their hands the fate of a possible African distribution for Sambizanga.

At any rate, I don’t want to make a “good little Negro” film. People often reproach me for that. They also blame me for making a technically perfect film like any European could do. But, technology belongs to everyone. “A talented Negro. . .” you can relegate that concept to my French past.

In this film I tell the story of a woman. It could be any woman, in any country, who takes off to find her husband. The year is 1961. The political consciousness of the people has not yet matured. I’m sorry if this situation is not seen as a “good one,” and if this doesn’t lead to a heightened consciousness among the audience as to what the struggle in Africa is all about. I have no time for films filled with political rhetoric. In the village where Maria lives, the people have no idea at all what “independence” means. The Portuguese prevent the spread of any information and a debate on the subject is impossible. They even prevent the people from living according to their own traditional culture.

In the village where Maria lives, the people have no idea at all what “independence” means. The Portuguese prevent the spread of any information and a debate on the subject is impossible. They even prevent the people from living according to their own traditional culture.

If you feel that this film can be interpreted as being “negative,” then you’re falling into the same trap that many of my Arab brothers did when they reproached me for not showing any Portuguese bombs or helicopters in the film. However, the bombs only began to rain on us when we became conscious; the helicopters have only recently appeared—you sell them to the Portuguese and they buy them precisely because of our consciousness. For, not too long ago, people here believed that all that was happening in Angola was a minor tribal war. They didn’t reckon with our will to become an independent nation: could it be true that we Angolese were like them, the Portuguese? . . . no, that wouldn’t be possible! . . .

I’m against all forms of nationalism. What does it in fact mean to be French, Swedish, Senegalese, or Guadeloupian? Nationalities and borders between countries have to disappear. Besides this, the color of a person’s skin is of no interest to me. What’s important is what the person is doing. . .

I’m no adherent of the concept of the “Third World.” I make films so that people—no matter what race or color they are—can understand them. For me there are only exploiters and the exploited, that’s all. To make a film means to take a position, and when I take a position, I am educating people. The audience has a need to know that there’s a war going on in Angola, and I address myself to those among them who want to know more about it. In my films, I show them a people who are busy preparing themselves for a fight and all that that entails in Africa: that continent where everything is extreme—the distances, nature, etc. Liberation fighters are, for example, forced to wait until the elephants have passed them by. Only then can they cross the countryside and transport their arms and ammunition. Here, in the West, the Resistance used to wait until dark. We wait for the elephants. You have radios, information—we have nothing.

Some say that they don’t see any oppression in the film. If I wanted to film the brutality of the Portuguese, then I’d shoot my films in the bush. What I wanted to show in Sambizanga is the aloneness of a woman and the time it takes to march. . .

I’m only interested in women who struggle. These are the women I want to have in my films, not the others. I also offer work to as many women as possible during the time I’m shooting my films. You have to support those women who want to work with film. Up until now, we are still few in number, but if you support those women in film who are around, then slowly our numbers will grow. That’s the way the men do it, as we all know. Women can work in whatever field they want. That means in film, too. The main thing is that they themselves want to do it. Men aren’t likely to help women do that. Both in Africa and in Europe woman remains the slave of man. That’s why she has to liberate herself. . .

People know nothing about Africa. That’s why I want to make my next film about King Christopher, a Haitian slave who led a rebellion that ended in a defeat for Napoleon, and then named himself king.

In this film I want to show that Africa also has a history, that Africans are not history less savages, but that there have been many outstanding people coming out of the culture of Africa. Aime Cesaire has given me all the liberty I want to rework the script. The film won’t only concern itself with events that took place more than one hundred years ago, but will also deal with the Africa of today and will include documentary material on Malcolm X, George Jackson, Amilcar Cabral, Schou Toure of Guinea, and others. The film will offer an answer as to why African countries which got their “independence” in the 1950s failed to keep it in the true sense of the word. By using King Christopher as an example. I’ll try to compare his failure with the failure of these “independent” African states.

King Christopher will be shot in Cuba. The Cubans have already promised all the help they can give as far as food and lodging and transportation are concerned. What still remains though is the raising of the necessary money for all the rest: actors and actresses, costumes, raw stock, etc. . .

No African country, with the exception of Algeria, has its own distribution company. In the French-speaking areas of Africa, distribution is handled by a monopoly that is in French hands. There is not one cinematheque nor even a so-called art cinema. . . All too often, you hear that there is no African film, or that if there is, it’s just Jean Rouch. That’s to make it easy for those who say such things. One day, we’ll come to France and shoot a film, then we’ll show the African people our view of France—that’ll be an entertaining film. . .

The Swedish, the Italian films and the films of other countries did not sprout up like mushrooms from the earth. In Africa there are several young people who are really talented filmmakers. We have to put an end to the lack of knowledge and the utter ignorance that people have about the special problem of Africa.

Personally, I feel that Sembene Ousmane is the most talented of our directors. He’s often reproached for financing his films with French capital. So what! The most important thing is that we have to develop a cultural policy that can help us. Show to the world that such a thing as African film does exist. We have to teach ourselves to sell our films ourselves and then get them distributed. Today we are like small sardines surrounded by sharks. But, the sardines will grow up. They’ll learn how to resist the sharks. . .

This text, first published in Women and the Cinema: A Critical Anthology, edited by Karyn Kay and Gerald Peary (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1977), presents Sarah Maldoror’s reflections on her landmark film Sambizanga (1972). Based on the novel by José Luandino Vieira and co-adapted by Mário Pinto de Andrade, the film stands as a defining work of pan-African cinema, chronicling the struggle for Angolan independence through the perspective of Maria, the wife of a political prisoner. Among the first feature films directed by an African woman, Sambizanga employs a carefully restrained visual language to expose colonial violence and the structures of oppression, emphasizing the slow emergence of political consciousness among the oppressed.