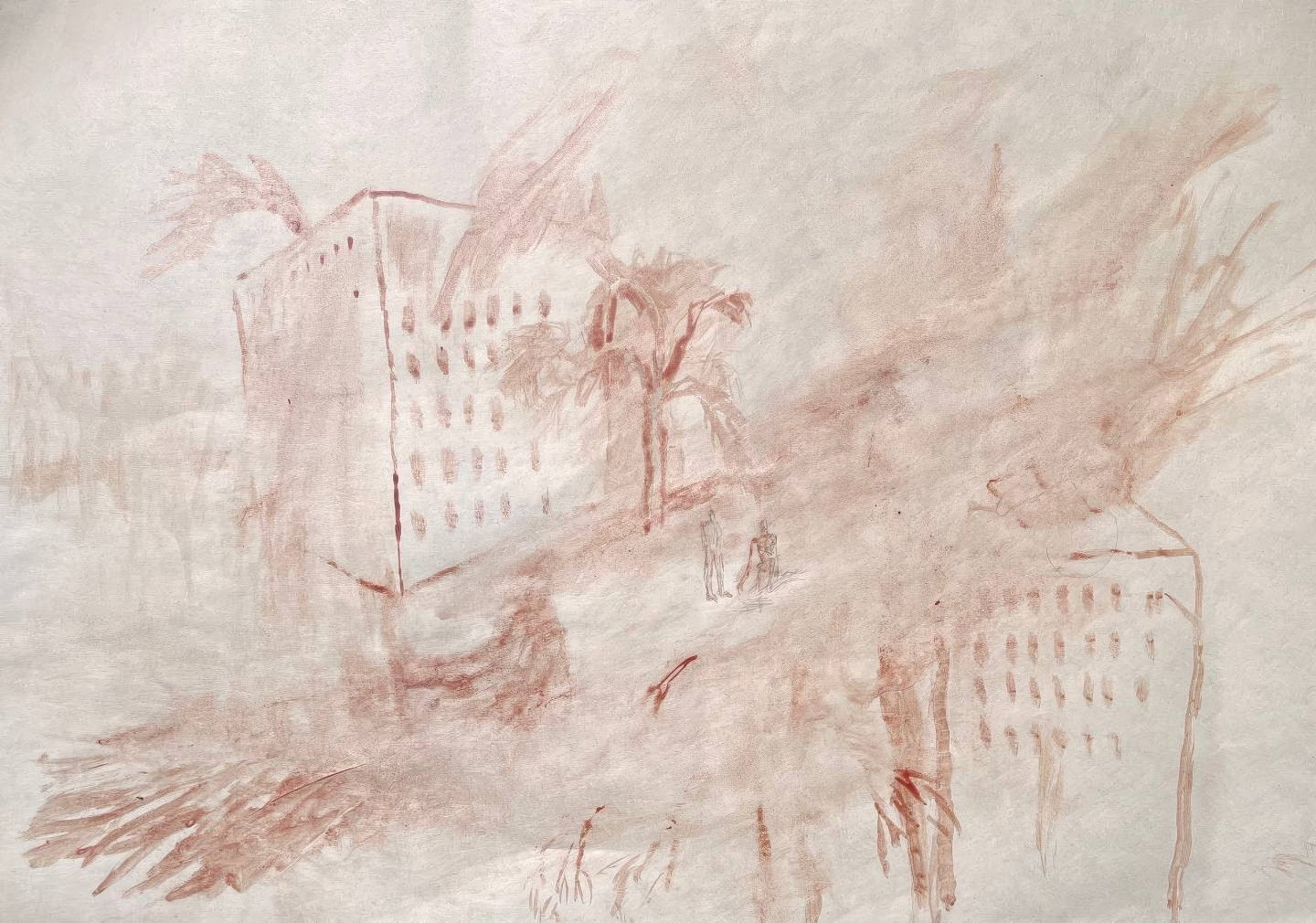

Nikita Kadan, from Shadow on the Ground series, 2022. Charcoal on paper, 30×40 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

The shadow appears in my Kyiv apartment during planned and emergency power outages, sometimes up to fourteen hours a day. It lives in a dark room lit by candles, flickering yellow—the color a little less saturated than in Rembrandt’s paintings. Another light source is the reflection from LED lamps and my laptop, charged by a South Korean power bank, on which I am writing this text. It is dark in the corners of the apartment, and the ficus tree standing by the window casts a highly whimsical silhouette. In this everyday routine, there is something simultaneously mystical and exceptionally practical that nails me to the reality of things and the subject of art in the age of technical production. This shadowy reality I live in has put before me the question of the shadow and its meaning in contemporary wartime Ukrainian art—light as a condition for existence and work, the image of the shadow as a metaphor appearing on the deserted walls of museums. In art history, there is yet another shadow—that of being in another’s shadow, a frequent story told of artists.

Over the last three years I have often returned to Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition, which, in my opinion, vividly illuminates human existence and the link between art history and the political realm. In the introduction, Arendt writes of eternity and immortality. For her, first and foremost immortality can be won through work—for example, artworks that remain after the death of the artist and become a part of private, museum, or public collections. These artists’ names will stay in memory and be inscribed in history through books, essays, cinema, public talks, and other types of knowledge production.

Yet “museums as a form are no longer relevant,” as one artist asserted in conversation with me. I argued with him. But at the same time, when someone asks me what has happened institutionally in the Ukrainian art scene over the last three years, I always mention the growing number of private apartment galleries, active art communities, and the role of grassroots initiatives that young artists choose over galleries and art centers. These new wartime communities are not often visible to bystanders. Established art institutions look constrained and conservative; museums are generally incapable of change. The pulse of Ukrainian art is happening elsewhere, on the outskirts, in the shadows, among cluttered apartment spaces. Periphery and shadow become necessary for digging, freedom, and experimentation.

Will this change after the war and with time? Will these newly created artistic spaces, which are outside the boundaries of the existing institutional infrastructure, not themselves become part of it and find themselves under the same conditions as those that came before? There is no answer yet, but these artist-run galleries and spaces provide something more substantial: safety (a basic need), as well as freedom and exchange. Here, the artist finds themself with the viewer, who is ready for anything. This audience will not be disappointed by or protest against an overly vivid or violent portrayal.

However, museums remain extremely important for understanding the complexity and completeness of history. Museums are also about the presence of this history.

I always come back to the question of interpretation. Researching late 1980s and early 1990s art, I often ask myself: How free can I be in my comments on these works? How do these works relate to the politically turbulent times in which they were created and to the wartime I live in now? Often they fall into the shadow of art history due to a lack of knowledge, archives, and presence in museum collections. However, one can always find answers in these works themselves to questions that press on us today.

For example, in 1993 Kyiv artist Valentyn Raevsky created the installation An Untitled for the exhibition “The Steppes of Europe: New Ukrainian Art” at the CCA Ujazdowski Castle in Poland. Inside the room he built slopes, imitating those of Kyiv. He created a massive pedestal between them and placed a tiny human figure on it. He projected light onto this monument, but the shadow that fell on the wall was enormous and many times larger than the figure of the hero himself. It is unknown to whom precisely this monument was built; for the artist himself, this figure was not so important, but the massive shadow symbolized the myth-making and rhetoric surrounding the figure.

This artwork was created in the early 1990s, when history was being revised: archives were opened, heroes of different eras reinterpreted, and a new identity and national myth were created. Who should remain on pedestals? Who should be removed from them, and who should go in their place? And who, in the end, was left in the shadow of history? The topic of historical and national heroes has always been attractive to artists. Since the beginning of 2014, it has acquired a new, acute meaning. But in Raevsky’s work, the shadow itself is more essential than the human figure. The shadow represents what people say, what and how critics write, how and whom generations remember—all our actions and words that bring the light and shape this shadow, increase or decrease it.

Karina Synytsia, Hidden in the Land of Trauma, 2023. Acrylic on paper, foil, 38×55 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

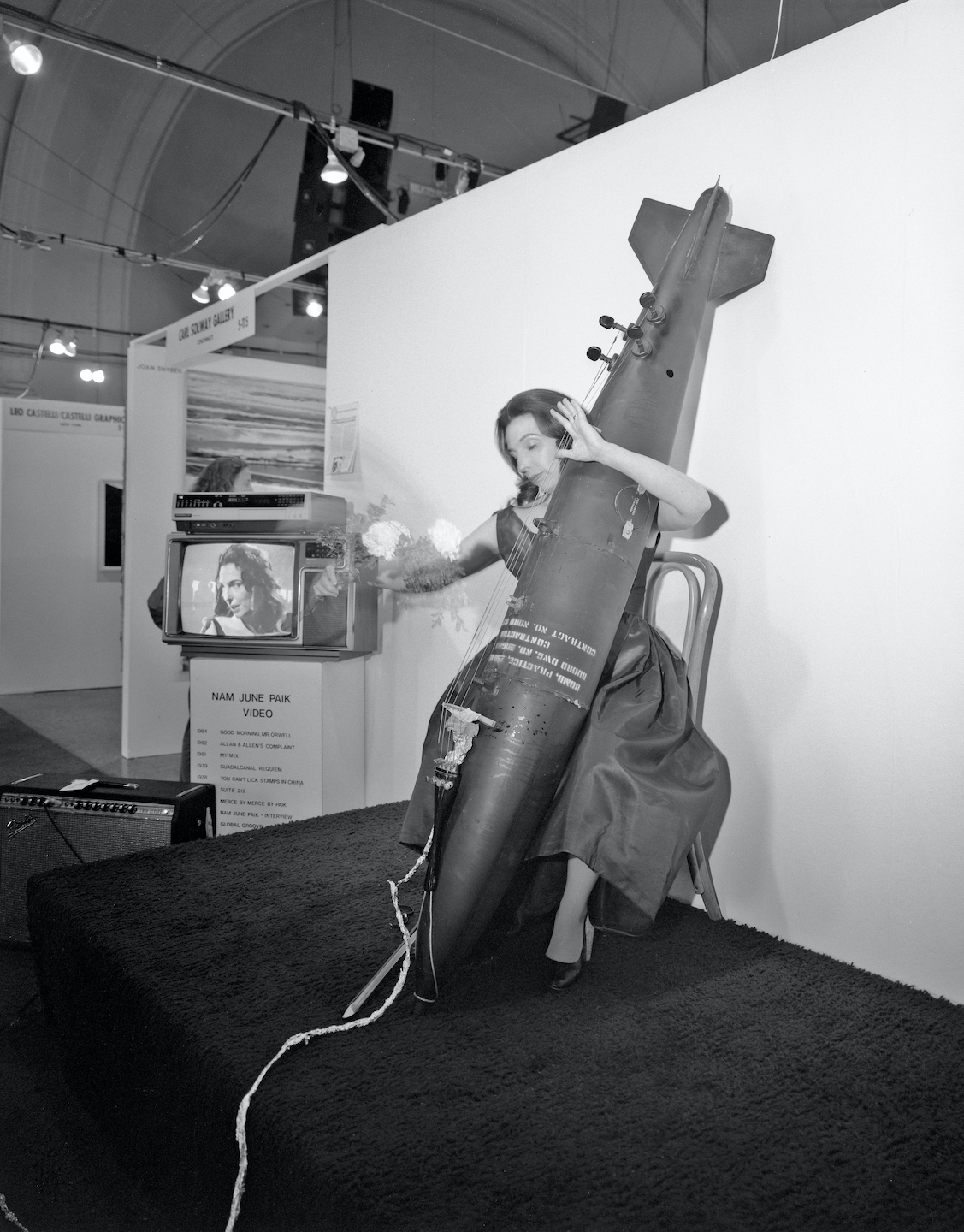

In 2022, the artist Nikita Kadan created a series of twenty-five graphic works entitled Shadow on the Ground. A similar image of a human traced on the land appeared in the paintings of a few other artists during these years. In the drawing Hidden in the Land of Trauma by Karina Synytsia, a person stands in the middle of a field and casts a shadow; she looks back at it, to grasp the scale of this shadow.

There is no human figure in Kadan’s artwork. Just as with Raevsky, the artistic space is focused on the shadow and the landscape. By contrast, in Synytsia’s drawing the figure of the man is precisely in the middle. It is drawn as timidly as this man’s step, action, or thought during the war.

If Kadan’s image is a “slap in the face of history,” Synytsia’s work is grounded in the figure’s experience of wartime living; it’s about human existence. There is shame and confusion in this drawing. The person depicted does not create history and is not its victim—although sacrifice is also present here. Instead, there is a misunderstanding of one’s role and place in history, a loss of landmarks, and a sense of oneself as lost—not just in history, but in one’s own life.

Kadan’s works speak of the long, bloody history of the twentieth century. The artist works with archives and tries to tell the stories of those who have been violently forgotten. The man in Synytsia’s image is someone who will be overlooked.

Karina Synytsia was born in Severodonetsk, Luhansk Oblast. The city was under occupation for a year in 2014–15. The artist studied painting in Kharkiv; now this city is targeted daily by the Russia army. Loneliness and alienation are the two main subjects her art practice.

The long candle next to me is melting, and its light despairs for a minute; I change it for a new one and the room becomes brighter, the whimsical shadows from the ficus growing less scary. What happened in this time while it was darker? Did it change anything in my room? In the news, they say that mobile power plants will be given to Kyiv. As one artist friend says, this is the future because it will allow the system to be decentralized. In fact, decentralization at all levels will make it difficult for the enemy to de-energize the entire city and country because there will be additional power centers that can take over from each other. My second candle burns down by half.

Light and shadow are precious in art history. They are often formative and figurative and help the viewer understand perspective and shape. Light and shadow also give rhythm to history.

A Ukrainian woman painter told me, “I am not a real painter; there is no perspective in my works.” I tried to convince her that not all visual art has to meet these criteria. Sometimes what is critical is not so much the perspective depicted on the canvas but the perspective of the artist herself—things like having the space for work and a daily routine, the opportunity to visit exhibitions, and to participate in exhibitions. To find a light. And even more critical: to survive and stay alive. It’s about basic needs and human conditions. Unlike men in Ukraine, this artist can leave and live anywhere. But she returned to Ukraine, choosing this perspective and taking these risks.

Living in a state of war raises the question of human choices and whether they exist. How can the body remain intact and not break down when living in a landscape that is constantly being destroyed and deformed? What prospects are there?

Should one depend on foreign electricity generators, or trust the traditional materiality of candles that melt before your eyes?

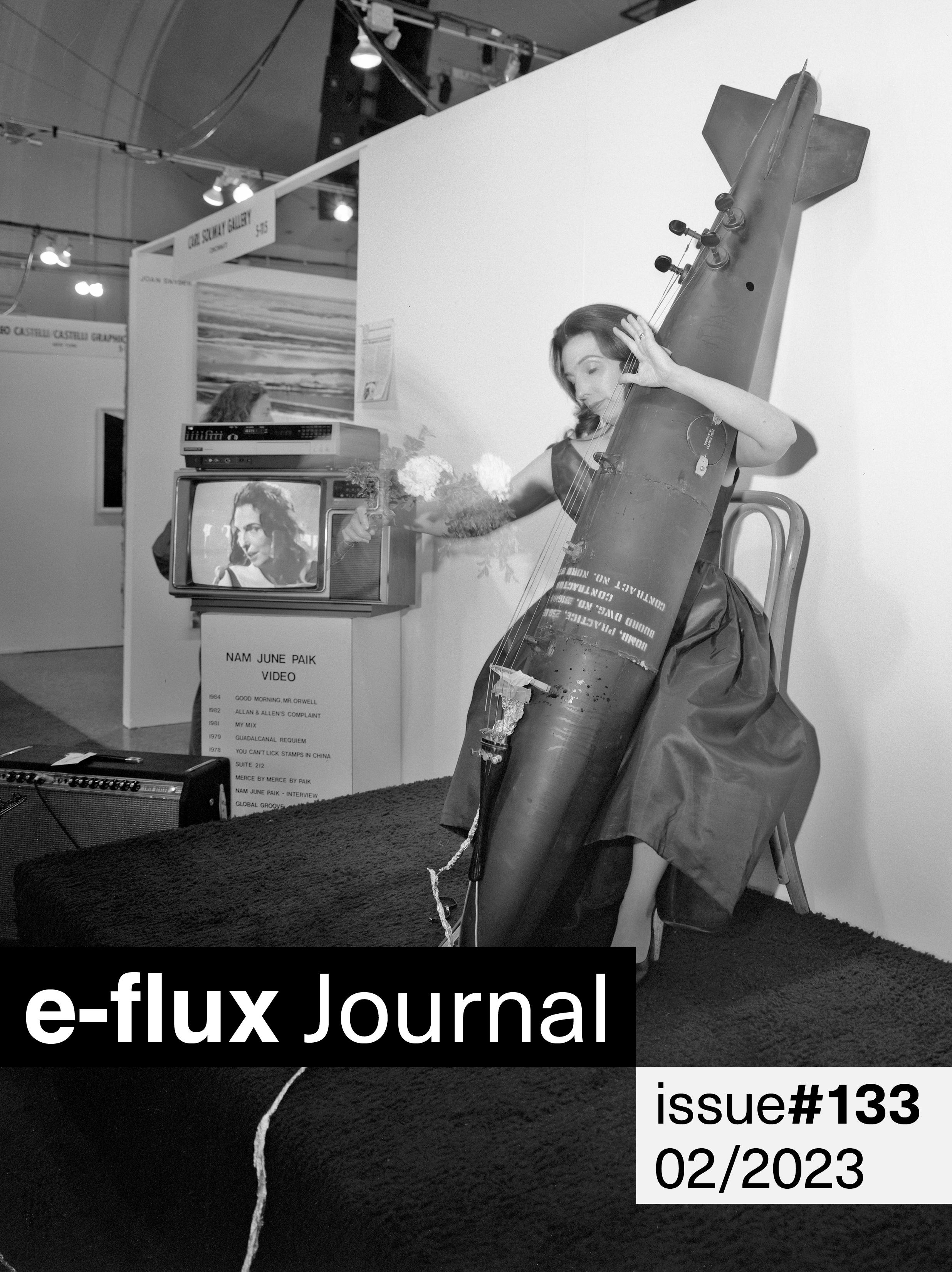

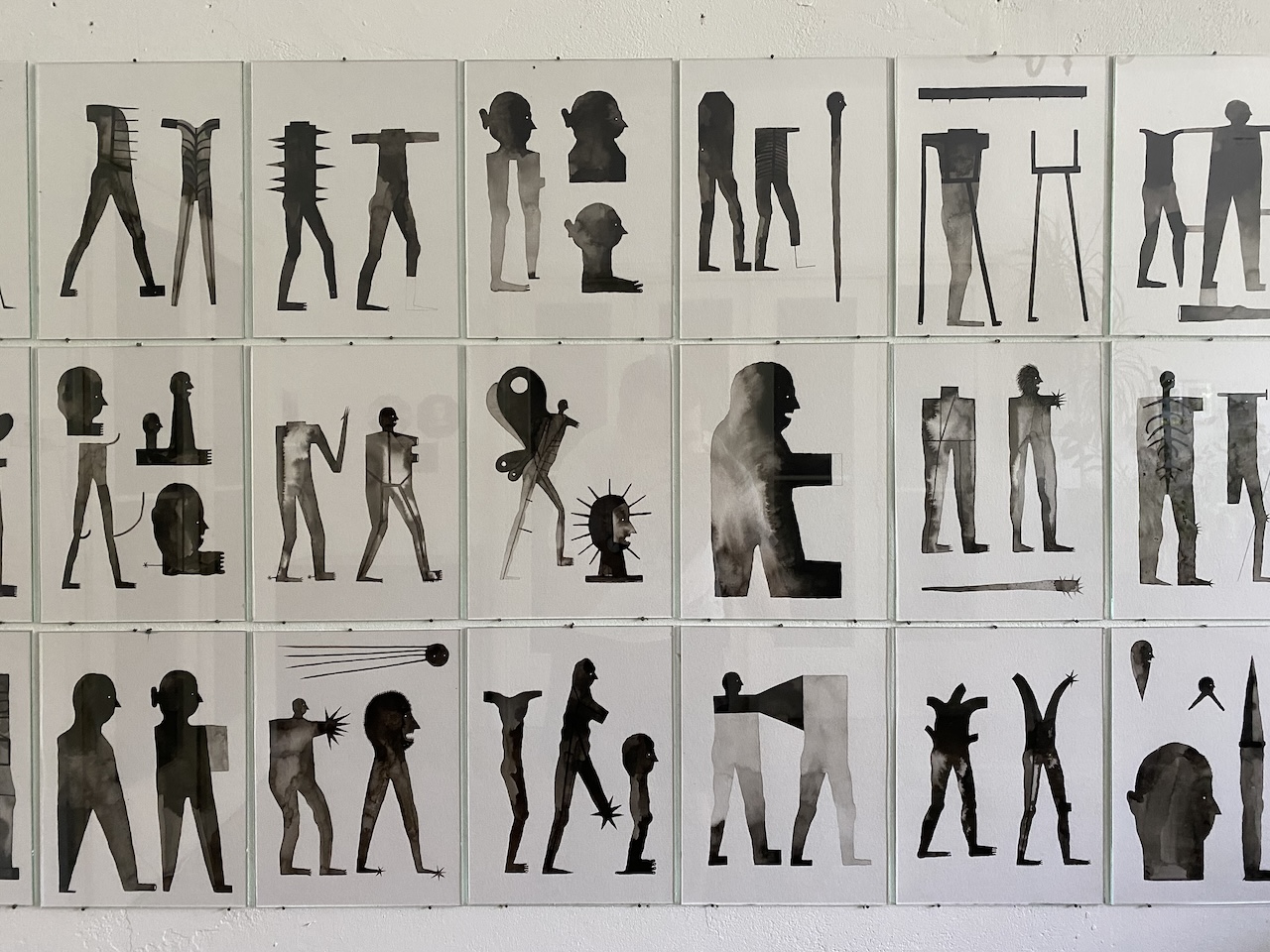

Exhibition view of “Pretty Stable Perspectives,” Yaroslav Futymskyi, curated by Boris Filonenko, Mizhkimnatnyi Prostir (artist-run gallery), Lviv, Ukraine, July 2024. Courtesy of the curator.

The answer to this question is ironic. It can be found in the title of Yaroslav Futymskyi’s exhibition “Pretty Stable Perspectives,” which featured, among other things, a series of graphic images depicting human bodies that had no gender and no limbs—the future society of those who are broken and lost. The exhibition took place at an artist-run space created in March 2021 in Lviv. Since then, it has hosted many important exhibitions for the local community, but now it is less active and faces new risks. The artist and curator who created this show also face their own risks; they might be sent to the front at any time.

As a child, I was terrified of the dark. I grew up in a small industrial town in eastern Ukraine in the 1990s. In my memory this time is marked by a lack of electricity amidst my otherwise bright childhood, which was not yet tainted by dirt, dust, and trauma. My childhood unfolded among flickering light bulbs in apartment-building entrances. It often seemed that in the dark corridors of high-rise buildings for mine workers, strange figures or vagrants were hiding. After all, shadows are a refuge for the lonely and the abandoned. As a researcher of contemporary art, I often look into shadows—especially the shadow of history, where I search for answers to questions about the present. I find answers, but often it takes a long time. Do I have enough time? The candle has almost burned out.

Am I afraid of the dark now? Among all my fears, one remains: that this shadow will cover everything, and there will not be enough light left to see and recognize the shadow. However, the experience of living in blackouts has taught me something: the shadow does not come out of nowhere; there is no shadow in an empty space, except our own shadow. Therefore, a shadow is evidence of existence and presence in the landscape.

—July 2024, Kyiv