Liquid Dependencies is a collaborative endeavor between Yin Aiwen, Yiren Zhao, and Mengyang Zhao. The present essay is authored by Yin Aiwen and presents her perspective on the ongoing design research project Alchemy of Commons, created in close collaboration with Yiren Zhao, a community organizer, researcher, and educator with an MA degree in psychology. Unless specified otherwise, the term “we” pertains to the joint efforts of Yin and Zhao.

See →.

A. Yin and G. Castello, “Social Discrepancies at Stake,” ReUnion Network Document, Spring 2020 →.

Keller Easterling, Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space (Verso, 2014); Nils Gilman and Ben Cerveny, “Tomorrow’s Democracy Is Open Source,” Noema, September 12, 2023 →; Benjamin H. Bratton, The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty (MIT Press, 2016).

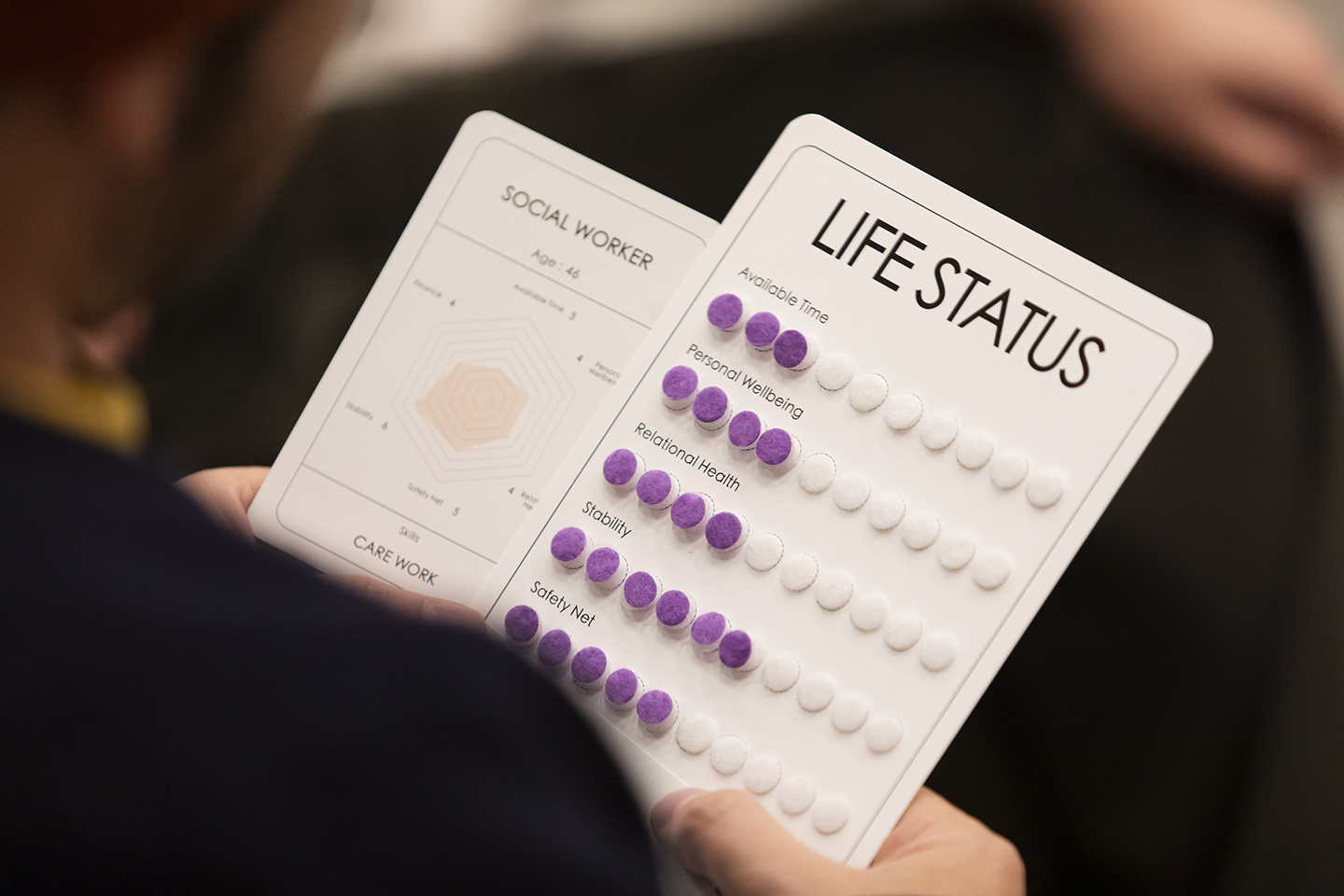

We design the characters and plots that people play in the game. While there are a total of forty characters and 120 plots available, a single session of the game requires only ten characters, and about fifty plots will be played out. In this way, we make sure the fictional society in each session is random and different.

Sylvie Vanwijk “Residential Report | The City with Intention,” Liquid Dependencies, May 23, 2022 →.

Alchemy of Commons was founded in 2019. For more info see →.

Our research uses the terms “collective” and “self-organized community” interchangeably, depending on the context. We have observed that when a group wants to present a united front for representational value or to exercise agency in the art field, it tends to call itself a “collective.” When a group wants to emphasize its communal nature and interpersonal relationships, “community” is the preferred term.

The Dinghaiqiao Mutual-aid Society (DMaS) was initiated by artist Yun Chen in 2014, in collaboration with participant-in-residence Yiren Zhao. Between 2014 and 2017, the project was an artist-led, mission-oriented initiative that offered public-facing programs. After Chen left the project in 2018, Zhao implemented a “co-op plan” to transform the initiative into a self-organized community oriented toward collective action through self-reflection and mutual aid. My interest in DMaS began during the transitional phase of the initiative, which was a rare example of a successful shift from an artist-led to a community-owned project. Later, Zhao and I shifted the focus of our collaborative work, to the ontology of community.

Andrew X, “Give Up Activism,” Do or Die: Voices from the Ecological Resistance, no. 9 (2001) →.

Stephen Karpman, “Fairy Tales and Script Drama Analysis,” Transactional Analysis Bulletin 7, no. 26 (1968). Karpman built on the work of Eric Berne, the founder of transactional analysis and a specialist in interpersonal psychology. Since Karpman proposed his drama triangle, it has gained popularity in psychiatry, especially for treating family estrangements.

Liberation psychology was founded by Martín-Baró and his Latin American peers in the 1970s. It sought to use psychology to help the oppressed identify the structures that oppressed them and to liberate themselves from them. In recent decades liberation psychology has influenced discussions in fields like Indigenous studies, Black studies, and feminist studies. To name a few: Belle Hooks has written extensively about the relationship between love, healing, and justice-seeking. Criminologist Howard J. Zehr pioneered the concept of restorative justice as a healing approach to justice. Critical social justice scholar Loretta Pyles published Healing Justice: Holistic Self-Care for Change Makers (Oxford University Press, 2018) to promote the importance of self-care in sustainable change-making.

See, for example, the Art and Solidarity Reader: Radical Actions, Politics and Friendships, ed. Katya García-Antón (Office for Contemporary Art Norway / Valiz, 2022).

Yin Aiwen, “Utopia in Progression: on the Social Relevance of the Arts in the 21st Century,” LEAP 艺术界, May 28, 2024 →.

The “European Funding Model” is a term I coined to capture the technocratic logic behind the funding of socially engaged art. It starts with policymakers who create funding mechanisms, like grants, to incentivize changes in society. Investors and philanthropists fund these grants, which in turn go to institutions or commissioning bodies, who then find suitable artists to commission based on the grant guidelines. The commissioned artists then create work intended to make an impact on the target audience. Ideally, the target audience will emerge with a changed mindset. For more analysis of this model see Yin, “Utopia in Progression.”

Yin Aiwen with Yiren Zhao, “The Solidarity Trinity: Or What Happens to Solidarity in the Arts,” Arts of the Working Class, January 16, 2024 →.

We are not the only ones to work in this direction. Future Art Ecosystems is another major endeavor that explores common ownership, in their case based on blockchain technology. See →.

See “the problem of maintenance” in Yin, “Utopia in Progression.”

Community feeling (or “social interest”—Gemeinschaftsgefühl in German) is a phenomenon described by the Austrian philosopher and psychiatrist Alfred Adler, the founder of individual psychology. Adler wrote that an individual’s community feeling depends on an acceptance of the self, the ability to trust other people, and a willingness to selflessly contribute. In Alchemy of Commons we adapted this trio of concepts to gauge whether an individual develops a capacity for commoning as they go through collective actions.

The four elements of a community are a work in progress which needs more (counter)evidence to support or rebut the theory. The current four elements come from David Graeber’s Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value (Palgrave, 2001).

There are three modalities in the chart—Infrastructural, Transformational, and Self-Realizational—suggesting that there are three ways for communities to express their mission. The Infrastructural modality is made up of the Space and the Economy axes, implying a location-bound community that invests in infrastructural stability. The Transformational modality is made up of the Relationship and the Ideology axes, which usually leads to a network-driven community focusing on transformation at various scales. The Self-Realizational modality is made up of the Labor and the Healing axes, pointing to a mission-oriented community. A community can be a mixture of all three modalities, but it might have higher expectations or be stronger in one of them.

Tokenomics, which combines “token” and “economics,” refers to the economic aspect of a blockchain or cryptocurrency project, often centering on the design and circulation of the project’s native digital token. Mutual Coin and its distribution logic are the tokenomics of the ReUnion Network and Liquid Dependencies.

See the report from Kunsten’92 on the situation of the culture sector in the Netherlands →.