Over the past three decades, the global art world has thrived thanks to the infrastructures of peak globalization; it has consequently internalized value systems that are embedded in the alignment between liberal democracy, the progressive state, and neoliberal metrics of economic stability. This alignment produces auxiliary notions in the art world that operate quite self-sufficiently—notions about certain artistic forms of production or distribution that embody liberal and progressive values in themselves, and about artistic “freedom” as a condition, rather than a product, of the system.

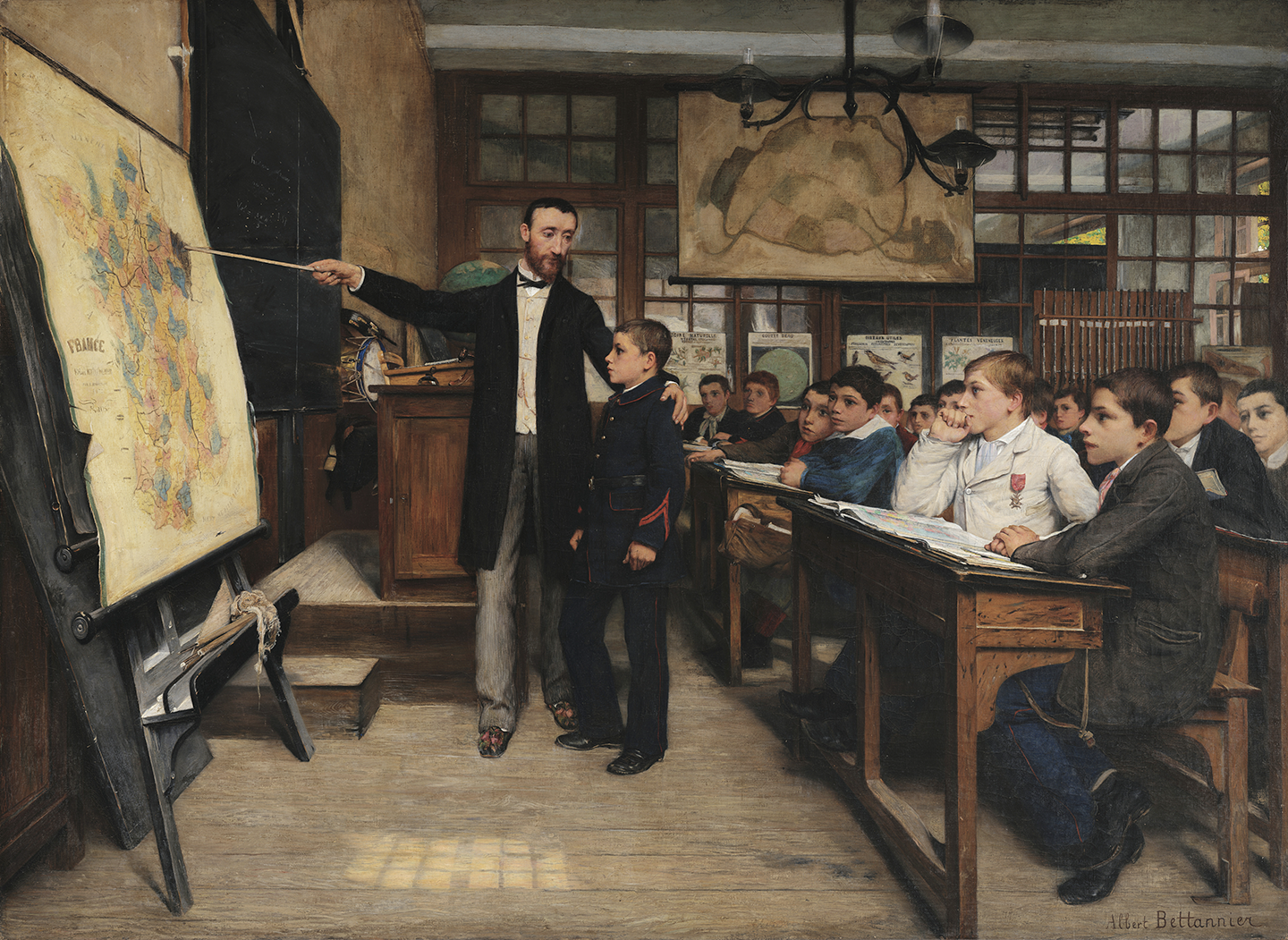

Art has always had a strange relation to power, whether in the service of royals and merchants or as a form for revolutionary vanguards’ imagination. Today the relationship has become even more complex, especially as the structures that have underwritten contemporary art shift beneath our feet—open markets close, soft power hardens into war, and populist sentiment becomes public life. One can say that, on a very high level, power itself has become highly unstable. In this special issue of e-flux journal, guest editor Mi You proposes that this instability is accompanied by a malleability, but also by a problem of representation that demands the immediacy of realism: a transfer of hopes and expectations to a calculus of means and ends. What would it mean to tactically revisit sites of oppression like capital and the state, but as fluid bodies that might be repurposed as levers? If art still corresponds to social progress, do notions like freedom and equality need new vision or should we rather prepare for what follows their ruin?

Kojève’s journey from philosophy to diplomacy was not a case of accidental wandering but the outgrowth of his Hegelian convictions. He held that critique without action is frivolous, dismissing the “fundamentally nihilist elements, known as ‘intellectuals,’ for whom non-conformity is in itself an absolute value”—those who, like Albert Camus, reveled in moral dissent yet sidestepped the arduous institutional work needed for durable change. A critique, Kojève said, that wants to be taken seriously cannot operate at a distance from the state.

The overwhelming emphasis on science in Chinese society and its education system means that analyzing and discussing science and technology has become central to the culture today, much as explorations of urbanism and cultural change were a generation ago. If a decade ago the Chinese economy manufactured products for the West, and elites sought to join or access the West via emigration, education, and real estate, today the dynamic parts of Chinese society are aimed at creating popularly accessible technology to improve the lives of Chinese people—and then export it to the Global South.

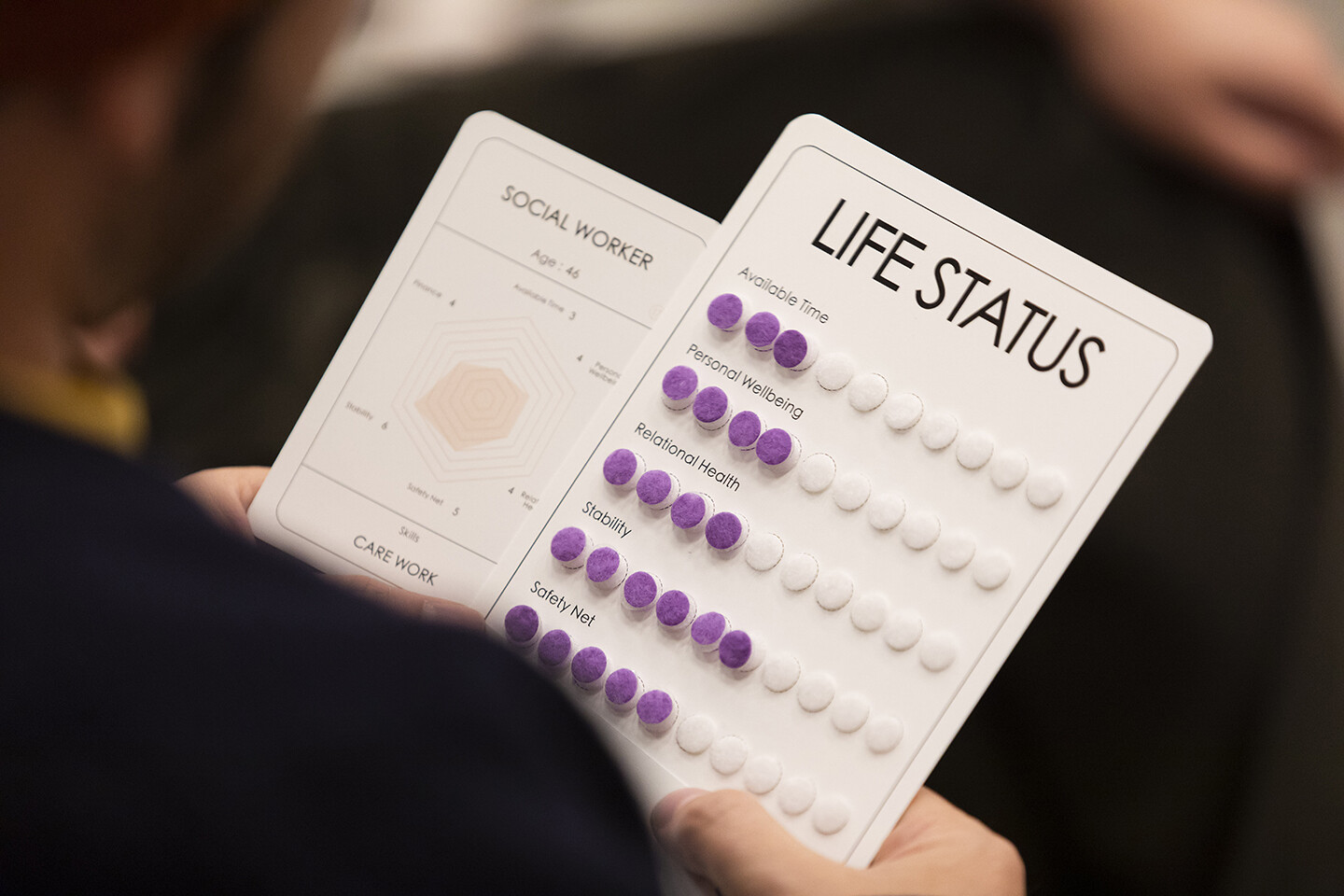

But is such emancipatory potential congruent with game mechanisms that are inherently violent or that establish agonistic relations between players? Today, leftist game designers and many serious, cooperative, and social simulation games tend to eradicate these traits entirely. Rather, the scope and key challenges of such games designed as supposed forces of good appear dependent on the foreclosure of difference, nesting their stimulus instead in the pacification of subject relations and the othering of enmity. But this ethical commitment comes at a price.

The origins and development of nationalist movements have to be examined from the perspective of the geopolitics among major empires, rather than by building half-baked theories based on weaker sociopolitical forces such as ethnic identity, historical memory, the pursuit of national consciousness, advancements in communication and information exchange, and the diffusion of the nation-state political model. I am not suggesting that these latter factors are unimportant, rather that their role in shaping nationalist movements is first and foremost determined by the geopolitics of major empires.

The current art economy offers little incentive for artists to commit to long-term engagement with communities, as such efforts do not easily translate into professional cachet. Nor does the economy reward artists who share ownership or authorship through collective maintenance. In such an unrewarding environment, artists who commit to long-term change and communal collaboration effectively take the activist approach, making personal investments to pursue the social change they desire even though there is no promise of financial or other returns. This is a systematic inadequacy.

The advanced tools used to sequence, model, and analyze biological data provide unprecedented insight into the intricacies of life, yet they also reveal the boundaries of mechanistic certainty. As more aspects of the biological world become “datafiable,” vast amounts of information resist neat conclusions. Knowledge spills beyond singular narratives, challenging the models meant to contain it. Within these gaps—where data resists synthesis and certainty appears layered—it becomes necessary to ask what it means to know, and how human understanding fits into a universe that may never fully reveal itself.