I never thought being the “other” was a bad thing. On the contrary, where people tended to see subjugation and marginalization, I reveled in the potential for subterfuge. A film artist needs seductive powers—the sense of elusiveness and unknowability that comes with genuinely being an individual.

Those who make it possible to really live as a trans woman are rarely those who are our representatives to the other, and still less those who appoint themselves among us as the police of our supposed collective identity. Those who make it possible are artists. Not fine artists necessarily, nor writers of “fine writing.” They might work in minor, vernacular forms. They might just be artists of trans life itself. They might be undetectable outside of our little covens of care. They make up stories or images or gestures that elude the limits of what they, and we, were handed. Making it up as they go.

Irigaray made real for me an autonomy and a legitimation in my search for a livable self, and now it’s the subjecthood with which I write these words, full of femme feeling. Her unlikely trans feminism has worked well in that way, regardless of anything she’s ever written, or said, that is radically insufficient on other grounds. Here I am, a brown woman to her because I present myself as one and it’s not her desire to decide on my sexual difference or my subjectivity. French feminism of a surprising sort.

These days, “fem” has come to be used as a synonym for conventional femininity, and “queer” has come to mean “lesbian, gay, and bisexual” in a spicier tone of voice. This draining of political meaning from words we’ve called home has affected trans worlds less deeply than cis ones up to this point, but it is underway among us as well.

Something in me gave way that night. As quickly as I had thrown myself into this holiday, this escape from my work week, I had found myself detached, suddenly, just as fast.

Gender and sexuality are different, and the constant pairing of these issues in public policy sends a confusing message and fails to acknowledge our concrete gendered experiences. White women can create movements and tell stories and not mention Black women and those of color. Gays and lesbians can do the same and boldly practice transphobia. However, when Black women of trans experience speak, we are expected to fight for everyone. That is a Black woman’s narrative.

In Indonesia, “ludruk” is a performing art that functioned as public entertainment in the colonial era. You can find it easily in Indonesia’s East Java region, especially Jombang and Mojokerto. Ludruk involves transgender women, who in this context are called various local terms: “tandak,” “travesti,” “siban,” “banci,” or “waria.” The term “waria” is a combination of the Indonesian words “wanita” (woman) and “pria” (man).

The grassroots construction of trans community often happens in response to an absence of infrastructure, of support systems that allow for a life worth living. This construction of communal pathways of shared languages and practices is a laborious process that requires asking uncomfortable questions.

We tell ourselves stories in order to live, but what if these stories are too pulpy? The word “dissociation” is increasingly used to describe episodes in which feeling doesn’t feel like feeling, in which it can’t sufficiently get across the effects of personhood on the one hand and reality on the other.

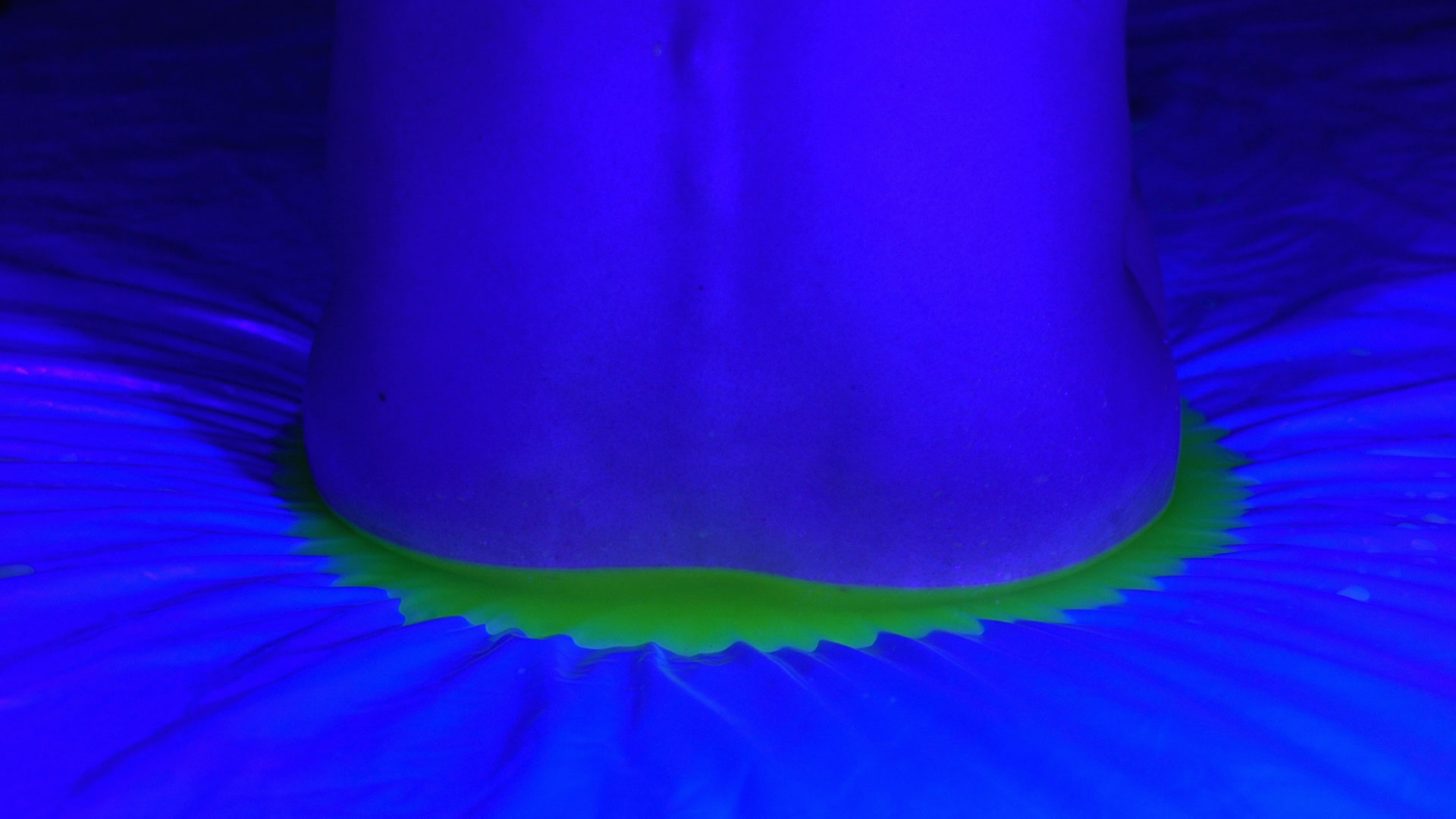

Bodies remain trouble. Irrefutable, unknowable, and seductive, bodies are what thought wants to escape but never can. All thought emanates from bone, muscle, skin, and nerve, and yet to think is as far as we can feel our own disembodiment.

I want to focus not so much on the male gaze, but on the cis gaze—a looking that harbors anxiety about the slippages and transformations between genders, but which also harbors desires for those transitions as well. I don’t want to think from the point of view of this dominating, controlling, and yet fragile cis perspective, nor even to critique it. I want to think, and feel, and imagine from outside of it.

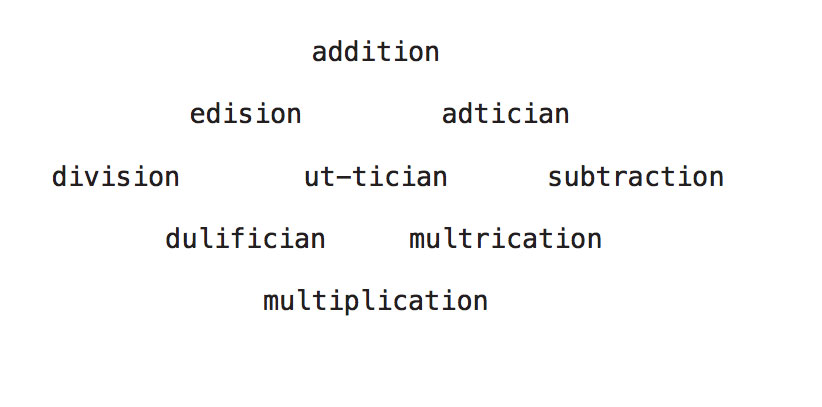

Rejecting “conventional language” itself seems like an appropriate project for trans literature; like feminist practitioners before us, trans writers are faced with creating inside of a discourse hostile to our particular subjectivity, using what works and discarding the rest.

The order of libidinal agriculture is the order of neoliberal totalitarianism in disguise. The couple form may look like a plot of land for individual use. But really it is an industrial production site for all sorts of capital (financial, cultural, social, emotional, etc.).