Frames within frames. A bed and an orange chair. The black-dressed figure kneels against the bed. Her clothes capture light in folds. Her terribly pink face is faceless—a flat surface missing its features. Her hands are fingerless. She is plains of paint, just as she is flattened by kneeling. Grief, anguish, or pleasurable submission, her facelessness refuses to show the emotional demand I place on her. Just as the canvas frames what it frames, the chair frames the body, frames the shape a body takes held in its rigidity. These frames—like the white framing of the figure itself, that pleated light—become indistinguishable from the flattened edges of the figure. Her body is a frame; she is flattened and does not so much struggle to emerge from the frame but, curiously, becomes the frame.

The more I look, there is nothing to see but framing. The painting proposes “her” as a frame, reflexively gesturing to the function of gender as frame. Framing as a technology of representation. Also, framing as a setup: gender is a setup, even those we choose or refuse (no-gender is also a gender setup). All these framings discipline, something that this figure yields to. But in doing so, I wonder if this figure also enacts a refusal to be known through the frame by being known as a frame. That is to say, in fore-placing the work of framing, the painting also gestures to what a frame never captures, never knows, never can show.

About her own painting, Erica Rutherford (1923–2008) writes: “Featureless faces opened their mouths in silent screams, as if horror at their deformity. Bodies were shockingly naked, with nothing to conceal their hermaphroditic lack of differentiation. If they had arms, they flung these out in despair into the surrounding darkness.”1

Rutherford finds her figures trapped between the absolutism of visibility (the role vision has in classification) and embodiments that have no representation. A paradox: overly visible and unseen. Existence that is nonexistence—that does not exist as existence itself. This is not utopic or liberatory; it is catastrophic. Her painted bodies witness the violence that the viewer (me, for instance) inflicts upon them in wanting to know—simultaneously naked (transsexual women are always already naked, contrived to be our sex first) and forced to scream out of mouths that are not theirs, not ours. What better description is there for the representation of transsexual women? “Her”—the race and sex that make this pronoun mean—is a problem that is central to Rutherford’s self-portraits in the 1970s.

1.

Bodies remain trouble. Irrefutable, unknowable, and seductive, bodies are what thought wants to escape but never can. All thought emanates from bone, muscle, skin, and nerve, and yet to think is as far as we can feel our own disembodiment. Audre Lorde and Judith Butler puzzled over the contradictions of embodiment, recognizing how systems of power and domination—particularly white supremacy and patriarchy—shape and reshape bodies as well as the feeling of bodily life. Even as they both suggested bodies are potentials—erotic and performative, respectively—everywhere violence defines the concatenation of bodies. They recognized that the unbearableness of bodily being thwarts every effort to represent—to think—bodily potential or plentitude. It is no wonder that thought—for this thinker—longs for a reprieve from—to literally, get out from—the impossible demands of bodily existence. And yet, Lorde and Butler both understood that disembodiment or transcendentalism were the very drive of white supremacist patriarchy.

In trans studies, body trouble is paramount. Through ever-changing names—transsexual, transgender, trans, trans*, genderqueer, nonbinary, and gender nonconforming—trans studies has no more central a problematic than embodiment. Trans studies has followed the feminist principle that gender ought to be capacious, disrupting the presumptions that biological assignment of sex (male/female/intersex) scripts gender. Following this feminist tenet, trans studies has shown: 1) gender is relational, shaped as much by sociohistorical forces as by subjective processes; 2) nonbiological agencies override anatomy and the material body, contesting ontological orders; 3) gender is a condition of the autopoietic subject that can be invented and destroyed even as the social order (patriarchy and white supremacy) hyper-invests in ever-narrowing sex conscriptions.

Gender promised a reprieve from the difficulty of bodies—from sexed and sexual bodies—that thought wanted, especially in trans thinking. The capaciousness of gender—indeed, its ability to suggest ideation, agency, and sociality—emboldened proposals for trans heuristics. Trans is no longer obliged to be about gender or bodies, subjects or identities. Trans now finds attachment to any number of objects, disciplines, media, histories, and much more.

Many of these are arguably advancements in theory, but there remain reasons to question how an ever-expanding trans—built upon a logic of dematerializing gender—has made questions about bodies and sexes difficult to ask, even politically precarious to pose. Are there differences between bodies framed by the general term “trans”? For instance, are there material divergences between estrogenic and androgenic hormonal changes to bodies, or for those trans subjects that maintain their endogenous states? If not essential differences, might there be consequential and material differences between, say, white transsexual women (with a pronoun “she”) and brown gender nonconforming femmes (with a pronoun “they”)? Do these differences shape livability, survivability, not only in terms of racial embodiments but sexual ones as well? And most troubling for the maxims of trans studies, does embodiment differently materialize the experience of trans masculinity from femininity? How might the generalizability of trans have enabled transsexual men to mis-conceptualize the lived experiences of transsexual women? What attention is needed to think well about differences that a trans theory simply distorts, often with transsexual women remaining unthought or worse?2

This essay is an effort to think sexual differences—specifically, those of transsexual women who became through estrogen and surgery, which is also to say some women. Possibly, it means women who took canary-yellow Premarin® tablets as an act of wanting one’s self so exquisitely that only the language of necessity could approximate this desire. Needs are often primal wants that are too unbearable to describe as lust. These estrogens might have been prescribed with anti-androgen and progesterone pills. Likely, it means women who have been oversubscribed, undersubscribed, or mis-subscribed to the point of panic attacks, blood clots, strokes, unending nausea, and heart attacks. But also, women who have experienced nongenital orgasms that feel like bones cracking into lush velvet; a woman whose nipples achingly leak milk when she is afraid. All these—and numerous other contradictory effects of medicalized anti-trans violence, structural racism, and economic inequality—define them.

Premarin® meant, as it did for me, a woman who is sensorially redone—not male to female, but a sexed subject differently done in the effort to feel her body. Hormones, in this way, are not the same as medicalized embodiment, but instead are a supplemental register of sensation that is limited by sensory anatomy even as senses are excited over the edge of themselves. Simply, hormonal change remakes sensoria, and this begins to modify corporeality that subtends the senses. Touch, smell, and sight are disarranged, but not in the manner of some reductive “I see now as other women see”—that narrative is a hope for becoming a woman through her re-essentialization. Instead, bodily sensoria are percussed beyond our sense of sensed self. Sense vibrates, deranging the “feel of this” or the “look of that.” These transsexual women do not become “more woman” with hormonal change. No. But they do—I do—become another sex, not female and not male, but no less materialized sexually. This sexuality is not biologism, not essentialism, not absolutism. Which is not to say this sexuality is not consequential, differential, and substantial.

The bodies of these estrogenic women, these differently sexed women, are altered by social forces responding to them just as they are anatomically reacting to biochemical changes. Patriarchy and white supremacy—both are what make gender/sex, they are also the materials that make her—are cataclysms that all bodies are processed through no matter their resistances or privileges. Every effort to resist sex is also a confirmation of the racism and sexism of cultural and historical orders that translate such efforts.

Transsexual women are no different; we too become through these same catastrophes, we self-fashion with, from, and through the carnage of this violence. Even though my transsexuality makes me other to female or male, other to essentialism but no less material, my survivability (how I will die) is shaped by a very narrow social translation of my otherwise-ness. And yet, this is not to say that the desire to refuse social order is only purposeless, uninventive, or simply regressive. This is one of the paradoxes of wanting to change sexual difference into sexual differences.

Sexuality and sensation are these transsexual women. Not just in euphoric or positivist senses. Some wants are conscious and intentional fantasies that shape decisions. While others—often held hidden within those choices—are unrepresentable and intolerable, a negativity that magnetizes beyond what we know but is no less than what we want. Sensation sounds luxurious, but it is also the noise of “you fucking faggot” that vibrates into her body. A white man’s fists punching as he rapes is also assembling, as did his earlier oeillades. The systemic neglect of a neighborhood, planning decisions made to immiserate and segregate, environmental degradation and other structural forces are also the sensuousness that makes these women’s pharaonic bodies even as the curvature of her eye is altered by estrogen, seeing differently her place in this same neighborhood.

Both want and sensation necessitate bodies, and even the wish to be bodiless is a bodily fantasy. There is nothing new about this statement, but the discourse of trans (from its study to its activism) is framed not by differences or specificities but by generalities, sharedness, and cohesions. Dean Spade recently posted on Twitter: “Black feminist thought and Black lesbian analysis and organizing are and have been essential to trans liberation. We can’t build a trans politics that actually improves trans lives (instead of just using trans lives to justify and decorate the status quo) without it.”3 Rightly invoking the centrality of black feminist and lesbian thought for thinking about the racial logic of sex/gender systems, Spade’s “trans” and “we” eschew a similar commitment to difference and specificity. Could it be that an unspoken white trans masculinity is this “we”? Is this “trans liberation”? The very distortions that Lorde diagnosed—a repudiation of difference—are evoked here in a call for justice. This is not specific to Spade—he is but an example—but a more extensive problem within trans discourse—so many different subjectivities talking as one.

The generalizability of trans—not unlike the whiteness of liberalism—Spade’s point—obliterates the different (and often contradictory) organizing and building required to improve transsexual women’s lives, to improve black and brown transwomen’s lives. I agree with Spade: black, brown, and white transsexual women must grapple with the problem that femininity is capacitated through the fungibility of black femaleness. Femininity is a racial logic, and the desire for femininity is made possible through the sexuating capacity of antiblackness.4 This complexification of transsexual women’s lust for femininity deserves attention; we deserve the work of nuanced and difficult thinking. We can grapple with the racist logic of our own figuration—something that a generalized “trans theory” or “trans liberation” or “we” cannot provide. It is time to deconstruct “trans.”

2.

Frames in frames. A frame splits the figural body and the rectilinear shapes, canvases, pictures of the space the figure occupies, her space. “Her” is framed through style, but it is no less a frame, no less a structure of perception. What frames her space are fragmented language and blocks of color. The frame of language is foregrounded through its fragmentation; since I do not know the meaning of “new” or “ter pape,” I am confronted by the representational force of language, its hold for meaning. Her pinkness, her color is repeated in surrounding squares—surfaces that come to mean skin, epidermalization. Her and her pinky-whiteness are framed as frames. The frame we call gender is here a surface, an epidermalization. “Her” is produced out of surface, produced out of the racialization of her surface. Everywhere the painting points to the technologies of seeing, to the frame’s administration. And again, this faceless figure is a refusal of the frames that make her up, but only through the contradiction of becoming frame herself.

3.

How to think about a transsexual woman’s differences? By “a,” I mean a specific account among many. It could be called my transsexual method—I turn to art. For me, there is artfulness in transsexuality, and it is not her physician’s. Trans studies and activism advocate for the conservative position of transsexual women as needy literalists. Given that anti-trans violence imbues the sociopolitical climate, this position is understandable, but it conceals lustier questions with ontological certitudes—it is anti-sexual. The very act of her need for Premarin® or breast implants, or facial feminization and orchidectomies, are wants in the form, style, and feel of one’s sensuous self.

The misogyny and racism of surgeons and endocrinologists are obstacles for her want. Medicalization does not define a transsexual woman—just ask her. Medicalization is what repudiates her want even as it makes her otherwise to herself and others. She is not plasticized through medicalization.5 On the contrary, she is confronted with the limits of a cultural order (what structures her consciousness and preconsciousness, and the authority of the super ego) that materially translates her bodily sexuality, her art. Transsexual women’s bodies are accretions of intimate and subjective want made legible and experiential through the aesthetics of the cultural. What is art but a constant fight with—if also a reliance on—the protocols of aesthetics? Susan Stryker writes, “Nothing other than my desire brings Him [surgeon; but also, Medicine] here.” She continues: “Materiality always resists the symbolic frame. I beg it, then, to throw all language off and become ungendered flesh, but language clenches this meat between its teeth in a death-grip.” Invoking Lacanian terms, Stryker describes a paradox of transsexual women’s “desire”—what we desire happens within materiality’s resistance to representation, to representation’s commitment to the cultural. But, transsexuality is not the return of a real materiality stripped of the symbolic—of the really real—but about how sexuality intensifies and invents matter, even as it is conscribed by the cutting relationship between symbolic and real registers. In begging materiality, Stryker wants to reverse the cutting relationship that the symbolic performs. But perhaps her desire reveals that some women want what is also foreclosed—they want their want. If transsexuality is sensuous intensity, it is so because of sexuality; what I would call her artistry.6

Art and aesthetics produce a fractious join. Transsexuality is sexuality’s inventiveness with an impoverished reality, nothing more than the alibi for a brutalizing symbolic. It may be too contentious to say that transsexuality is artistry with modifications of sex as indexical signs of wantonness, but I offer this as an-other imaginary, an-other ego ideal for transsexuality. An artfulness at lusty odds with (and within) the cultural. This conversation risks but must avoid collapsing artistry into self-fashioning. Might her transsexual art-making aim toward a reprieve from the technology of selfhood? If art is the work of passion, her art also wants more than the cultural prescribes, more than the frameworks provided her. The art of transsexuality must not be confused with technologies of the self—seeing transsexuality as art places it as intervention in the material, rather than as confirmation of the reality’s authenticating and totalizing function. By “art,” here, I mean transsexuality’s sexualization of the sexed body, and the fashioning of sex as an act of artistry.

4.

In Nine Lives: The Autobiography of Erica Rutherford, Rutherford documents her varied life as an actor, filmmaker, theater designer, printmaker, painter, activist, and professor in England, the United States, Spain, South Africa, and Canada.7 A member of the Canadian Royal Academy of Arts, she painted for over forty years and was shown in major galleries in North American and Europe.8 Rutherford’s style ranged from abstract expressionism—murky fields of color that give way to swaths of luminosity that defined her work in the 1960s—to an oneiric modernism akin to Ken Kiff. Rutherford’s work in the dreamlike paintings of the 1990s step past the divides between abstraction and figuration by suggesting that fantasy is not opposite material reality but a contingent force in making the world.

During the late seventies, while undergoing sexual transition, Rutherford experimented with self-portraiture. Starting with a posed photograph of herself, she would paint from this photograph not to achieve realism, but to look at the function of photography, particularly its frame. Her flattened figures seem to merge with the apparatus of framing, both the photograph and the canvas. She pushes against portraiture’s cromulent function, and with it a modern conception of photography as capture. This period of work, I argue, refused photography’s privileged relationship to rendering transsexuality visible: from linear progressions of before and after to seeing transition as sexual binarism from zero to oneness, male to female, and also the collapse of the referent to the image-matter. Photographs accompanying transsexual memoires confirmed this narrow understanding. For the reader, the photograph demonstrated a seeing it—the indeterminate pronoun “it” working to materialize the transsexual transition. In contrast, Rutherford’s painted-self challenges photography’s conceit that it captures what really is.9

In Second Skins: The Body Narratives of Transsexuality, an inaugural text for trans studies, Jay Prosser writes about the connection between Rutherford’s paintings and her transition:

A painter, Erica Rutherford paints self-portraits based on photographs she first takes of herself dressed as a woman—also concretizations of an imperceptible self … These portraits begin by envisioning the woman Rutherford wishes to become and are gradually transformed as she transitions into a record of that becoming.10

For Prosser, Rutherford’s paintings are the sexual abstraction of her photographic becoming—to be, to be a woman, is photographic. Through photography, a transsexual emerges as a subject materialized into a real self. Here, Prosser pivots around the photographic referent to cohere the transsexual real with bodily matter.

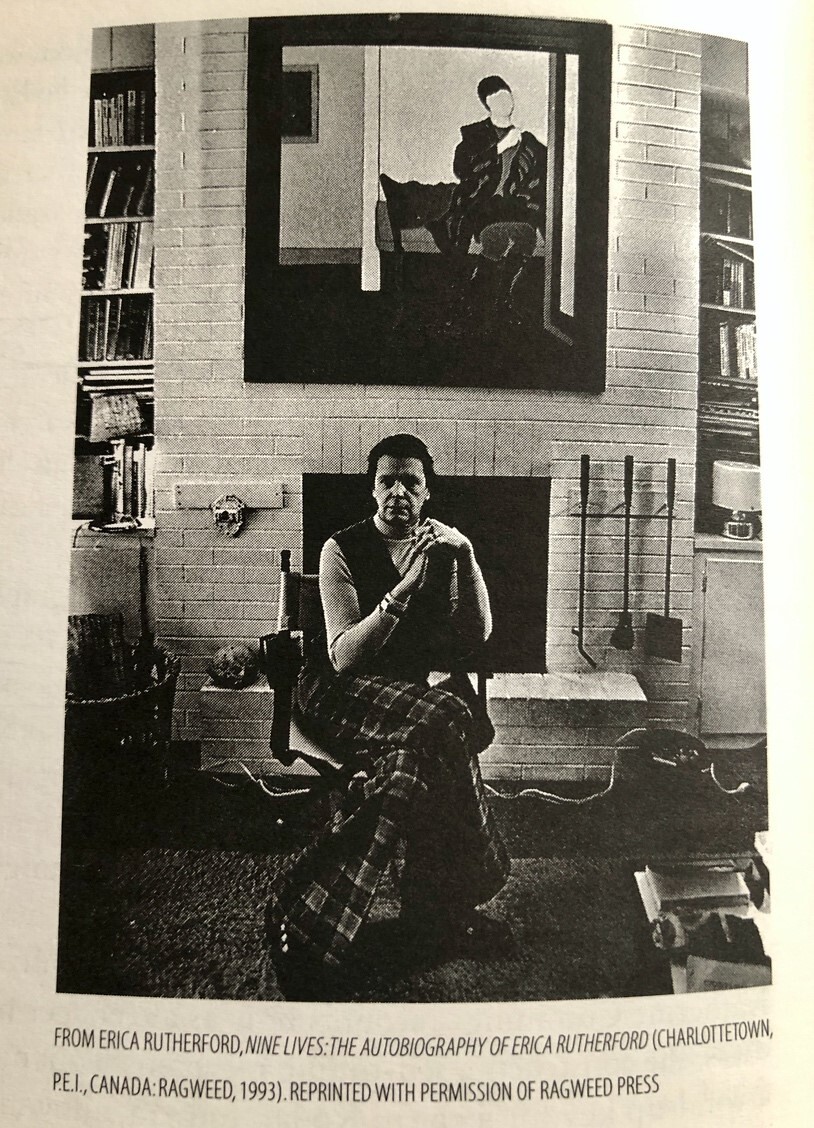

In discussing the above photograph in Rutherford’s autobiography, Prosser goes on to say:

A painted self-portrait is situated behind the photographic Rutherford. In the painting, the seated figure is feminized through body contour, posture, and clothing, but the face is featureless—a blank space as undetailed by the feminine as the still-masculine face of the photographic Rutherford seated before her.

Prosser continues: “The self-portrait is a blueprint for the transsexual subject in transition: like the photographs in the autobiographies for readers, visual means of making the transsexual’s gender real.”11 The real of her photograph, for Prosser, is her feminine failure—a failure the painting does not record. But, what if Rutherford’s painted portrait reflexively argues against the framework that her transsexuality is forced to represent here? Might the photographs she takes of herself be what Rutherford paints against, knowing that the photograph aims to render her transsexuality in terms of male to female, a sexual transition predicated on authentication and autopoiesis? Rather than collapsing her material body with the photographic referent, or confusing the real with matter, Rutherford’s paintings provocatively attend to the imperceptibility of perceptual frames.

Prosser understands how the apparatus of representation—for Second Skins, it is the narrative form of biography, which values a linear timeline and conflict resolution—attempts to capture the subject represented. Narrative progression has few better tools than transsexual transition to organize time and the arc of a story. However, Prosser concludes his book with the realness of sex as photographic, showing how the indexicality of photography’s referent substantiates the logic of sexual becoming. His study of “second skins” (his theory of transsexuality) ends with photography to lend it its own narrative resolution. Instead of recognizing the linear role photography plays in biographical accounts of transsexuality, Prosser turns to the photographic image as his theory of transsexual realness and bodily being. For Prosser, transsexuality is photographic: to be (seen/skinned) is sex itself: “For transsexuals surgery is a fantasy of restoring the body to the self enacted on the surface of the body.”12 Taking literally Roland Barthes’s assertation that photography is an indexical (literally “light … is a carnal medium, a skin”) record of “that which has been,” Prosser’s account of transsexuality is about that which is, about the realness of transsexuality as image, as photographic. Prosser is certainly not alone in building an account of transsexuality on a modern presumption of photography, but more consequentially, it seems to me that much of trans studies—what we might call its canon, its political orientations, its central commitments—has relied on an investment in the being of trans that it draws from photography as its defense and—perhaps even more impoverishing—as its logic.13 Trans studies has a photography problem.14

Prosser’s meditation on Rutherford initiates his argument about trans becoming that he theorizes through a particular photographic reading of Freud’s enigmatic statement about the ego as “not merely a surface entity, but … the projection of a surface,”15 that ultimately collapses the image-matter of skin and transexual being. In Prosser’s careful critique of Judith Butler, he demonstrates how she misreads the distinction Freud makes between body and ego. For Butler, the body becomes “itself the psychic projection of a surface.”16 For Freud, Prosser notes, the ego is a “product of the body, not the body as a product of the ego.”17 Butler conflates materiality with the mental projection of the surface of the body—collapsing the differences between Lacan’s mirror stage and Freud’s conception of the ego. Prosser makes the case that transsexual phenomena “illustrate the materiality of the bodily ego rather than the phantasmatic status of the sexed body: the material reality of the imaginary and not, as Butler would have it, the imaginariness of material reality.”18

In structuring this critique, Prosser turns to the cinematic imagery of Jennie Livingston’s Paris is Burning (1990) to show how Butler’s account of transsexuality is metaphorized away from the sexed and raced materiality of the body. In Butler’s own discussion of this film, she defines the camera as a metaphor of transsexualization: Livingston’s camera performs phallic maneuvering through transsexual women who want sex change (specifically, genital surgery), turning black and Latina transsexuals into confusions of phallus and penis. Prosser explains this confusion as a repetition of Butler’s misreading of Freud, again de-literalizing transsexuality. But what is interesting here is how similar Prosser’s turn to photography as metonymic of transsexualization is to Butler’s cinematic approach.

If, as Prosser suggests, the transsexual’s body image “is radically split off from the material body,” then the description of feeling “trapped in the wrong body” becomes uncannily similar to the capture of the referent in the emulsion of the photograph.19 An interior negative of the body image is printed—with surgery and hormones as processing fluids—onto and as the material body. “The skin is the locale for the physical experience of body image and the surface upon which is projected the psychic representation of the body.”20 Prosser recognizes the problem of Lacan’s occularcentrism of subjectivity, noting that that Freud emphasizes bodily sensations as forming the ego. However, he pursues the substantiation of the transsexual feeling of wrong-bodiliness such that

surgery deploys the skin and tissues to materialize the transsexual body image with fleshy prostheses in the shape of the sentient ghost-body. The surgical grafting of materials endows the transsexual with the corporeal referents for these imaginary and phantomized signifieds, restoring their substance.21

Photography, it would seem, is the form of transsexuality, creating a photo-ontic. Haunted by referents—appeals to the real—transsexuality happens between referentiality and representation. The problem with transsexualization as photograph is revealed in Prosser’s wish that the referentiality of transsexuality is captured (trapped) in photography.

The consequences of the photo-ontic of Prosser’s reading become clearer in his later book Light in the Dark Room: Photography and Loss, where he critiques his own autobiographical impulse in using a photograph of himself to end Second Skins. Guided again by his reading of Barthes, Prosser recognizes that his literal (what Barthes described as studium) reading of transsexual photographs missed what photography cannot show (the photograph’s punctum) in its capture: affect. In returning affect (punctum) to transsexual photographs, Prosser writes, “This failure to be real is the transsexual real.”22 For Prosser, transsexuals never achieve their referents, never achieve the longing for their sexed referent. It is the un-becoming of sex bound with an overdetermined sexual visibility that defines his transsexuality. Yet, transsexual being remains, problematically, photographic.

Yes, Prosser’s punctum allows for the affective, but it continues to rely on a photo-ontic. By “photo-ontic,” I mean how the seduction of the photographic referent produces a collapse between image-matter and being in theorizing transsexuality. Even the trauma inflicted by the surgeon who cuts her up through an acting-out of racialized sexism—any transwoman who has modified her body knows exactly what I mean, either as fear or actuality—remains within this photo-ontic framework for understanding transsexual beingness. Prosser writes “The photograph incarnates because it takes the body of the referent … I may never recover my first skin. But the realization of that loss is my second skin.”23 His photo-ontic: not being is transsexual being as enacted through the logic of photography. Image-matter, even in its most evanescent and affective form, defines transsexual being. The implications of transsexual-as-photograph are that the transphobic logic of spectacular spectacle defines transsexuality, obscuring other “bodily sensations” that mark the work of sexuality.

5.

Rutherford writes:

Then, at the moment when they seemed most to threaten me, they staggered, dropped to the floor and in helpless crouched postures withdrew themselves. In this position, though smaller, they still thrived, fattening themselves, assuming sensuous curves of a sexuality they could never know, growing breasts that obtruded indecently from their infantile bodies until they appeared malformed infants, aberrations of nature. Capriciously, they now assumed joyful colors, reds and yellows, as if to ensure that no one could ignore their presence.24

Instead—and what I can read from Rutherford’s refusal—let us take seriously the sexuality of sex change: the want that cannot be fully metabolized by the social (ego ideals that refuse ideal egos) while modifying the real’s own becoming, its ongoing materializations, sexualizations, and concatenations.25 Perhaps instead of Rutherford’s paintings as naive accounts of her becoming a woman, her painting proposes that photography is the naive technology for representing transsexuality (let alone for modeling transsexuality on). Rutherford does not show who she is becoming but shows what forces—and cultural aesthetics—are at work in delimiting that emergence, that potential. Working against photography as record, against becoming real through photographic logics, Rutherford’s paintings draw attention to those technical modes of perception that limit what the body is or might be. And more specific to Rutherford: What if a realist theory of photography has produced reproducible narratives about transsexual women’s lives—even to ourselves—that refuse bodily difference and those experiences that exceed the sex/gender schema?

But Freud continues to define “projection of a surface” as a sensuousness that is derived from the body, but not as a literalization of the surface of that body. Embodiment—the sense of feeling bodily—is a sensuous rapport between affective states we might call inside and outside. At every point in this relay, fantasy makes sense of sensations refracted through an inaccessible, but no less significant, materiality. In other words, bodily sense is produced through sensuous excess, not through a precise organ of sensation. Might, then, transsexuality not be simply about skin—one organ dedicated to touch and vision—but an excess that has no representative? Despite Prosser’s critique of Butler’s imagistic (and as such, performative) reading of the body ego, he also organ-izes the body ego through a phenomenology of photography (a studium-only account of the body—what literally is present-ed—as described by Barthes in Camera Lucida), with transsexuality as idealized example. The referential surface—what I read Rutherford’s art working against—is the frame that delimits transsexuality into a visibility, into a logic of the photo-self as sex. For Rutherford, transsexuality is not ontologically a skin to be imagistically realized. Instead, transsexuality is what infuses the body (even as limit) with sexuality as a register of fantasy always aiming toward what is yet unknown, the otherwise that designates transsexuality.26

What would it mean for Rutherford’s paintings if we returned sexuality (not identity, but libido) to transsexuality? To “assume sensuous curves of a sexuality [we] could never know”?

Erica Rutherford, Nine Lives: The Autobiography of Erica Rutherford (Ragweed Press, 1993), 168.

See Che Gossett and Eva Hayward, “An Introduction,” in “Trans in the Time of HIV/AIDS,” ed. Che Gossett and Eva Hayward, special issue, TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly 7, no. 4 (November 2020).

Dean Spade (@deanspade), Twitter, January 26, 2021 →.

Zakiyyah Iman Jackson, Becoming Human: Matter and Meaning in an Antiblack World (NYU Press, 2020).

See Jules Gill-Peterson’s important book Histories of the Transgender Child (University of Minnesota Press, 2018). Her argument complexifies the relationship between institutionalized medicine and subjective life.

Susan Stryker, “The Surgeon Haunts My Dreams,” Transsexual News Telegraph, no. 6 (Spring 1996). Under the title “Pre-Operative.”

While in South Africa, she worked against apartheid and the rise of the nationalists, producing the first all-black feature film in Africa’s history. “Her hope was nothing less than the establishment of a black cinema in South Africa.” Ray Cronin, in Cronin, Irene Gammel, and J. Paul Bourdreau, Erica Rutherford: The Human Comedy (Confederation Centre of the Arts, 1998).

New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the Arts Council of Great Britain, the Canada Council Art Bank, Arts Council of England, Confederation Centre Art Gallery, Indianapolis Museum of Art, and Museo d’Arte Contemporano in Madrid, Spain.

Feminists Bernice Hausman and Catherine Millot play out this collapse in their studies of transsexuality. In Changing Sex: Transsexualism, Technology, and the Idea of Gender (Duke University Press, 1995), Hausman’s attention to how technology (rather than narrative) constructs transsexuality curiously elides the role photography plays in medicine and the structure of autobiography. In Horsexe: Essay on Transsexuality (Autonomedia, 1990), Millot offers a Lacanian study of transsexuality. Following Lacan, she writes: “In their requirement for truth … transsexuals are a victim of error. They confuse the organ and the signifier” (143). Curiously, this claim is punctuated with photographs of transsexuals, demonstrating her own collapse of image and matter—the error she defines transsexual women as. Note: Her essay is often misread as saying transsexual women suffer from psychosis, but she is very clear that the transsexual woman substitutes The Woman for the Name-of-the-Father. “This fourth ring (The Woman in Lacan’s Borromean knot), however, only holds the Imaginary and the symbolic together; the real is unknotted, and the transsexual’s demand is thus for correction that will adjust the Real of sex to the knotted I and S” (45). This substitution is how psychosis is avoided, in Millot’s reading.

Jay Prosser, Second Skins: The Body Narratives of Transsexuality (Columbia University Press, 1998), 211.

Prosser, Second Skins, 212.

Prosser, Second Skins, 8.

Trans studies’ struggle with beingness has played across different concepts, including ontology, realism, materiality, reality, and Lacan’s real. Even in the introduction to “Left of Queer,” Social Text 38, no. 4 (2020), Jasbir Puar and David Eng variously cite “bodily materiality,” “ontology,” “matter,” and Lacan’s “return of the real.” Unintentionally, they too are tracking the imprecision and collapsibility of these dimensions of existence. That trans studies has welded these differences into indistinction may be less about carelessness then about the accomplishment of gender as pliability, as indifference. And I would add that the logic of this indifference is predicated on a disavowal of sexuality (what structures Lacan’s real).

This begins to explain the field’s whiteness problem. See Jonathan Beller, “Camera Obscura After All: The Racist Writing with Light,” Scholar & Feminist Online →. See also Chela Sandoval, Methodology of the Oppressed (University of Minnesota Press, 2000), and Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (University of Minnesota Press, 2003).

Sigmund Freud, The Ego and the Id (Norton, 1989), 20 and 20n16.

Prosser, Second Skins, 41.

Prosser, Second Skins, 41.

Prosser, Second Skins, 44.

Prosser, Second Skins, 69.

Prosser, Second Skins, 72.

Prosser, Second Skins, 85–86.

Prosser, Light in the Dark Room, 172, emphasis in original.

Prosser, Light in the Dark Room, 186.

Rutherford, Nine Lives, 169.

This point is taken up in a forthcoming “Part 2” essay on Erica Rutherford’s later work. Briefly, what that essay considers is the sensuousness of transsexuality. Attending to estrogenic and surgical processes, the essay offers a sexual theory of sex change.

Which then frames for us the question: Is anti-transwomen violence about envy—not hate—in the form of a misreading? By “envy”—given the social aesthetics of femininity that transsexual women are obliged to reproduce despite their refusal—I mean: “This transsexual woman not only has something I cannot have, but they stole it from me.” Envy is desire disavowed as parlous property: for the watcher of transsexual women, this envy is built through an error in presuming to see the real of her transsexuality. Is anti-transwomen aggression, then, an effect of an anti-sexual social that claims the feminine real for itself? Adding to the difficult question I posed early, in what ways has Prosser (but also any number of transmasculine scholars) used transsexual women to make a case for himself as seen? Rather than improve transwomen’s lives, does this scholarship self-vitalize through a repudiation and de-complexification of these women’s lives—so much so, that the only useful transwoman is a dead one?

Deepest gratitude to McKenzie Wark who encouraged me to get back to the pleasure of my text. This essay would not have happened without her support and editorial guidance.