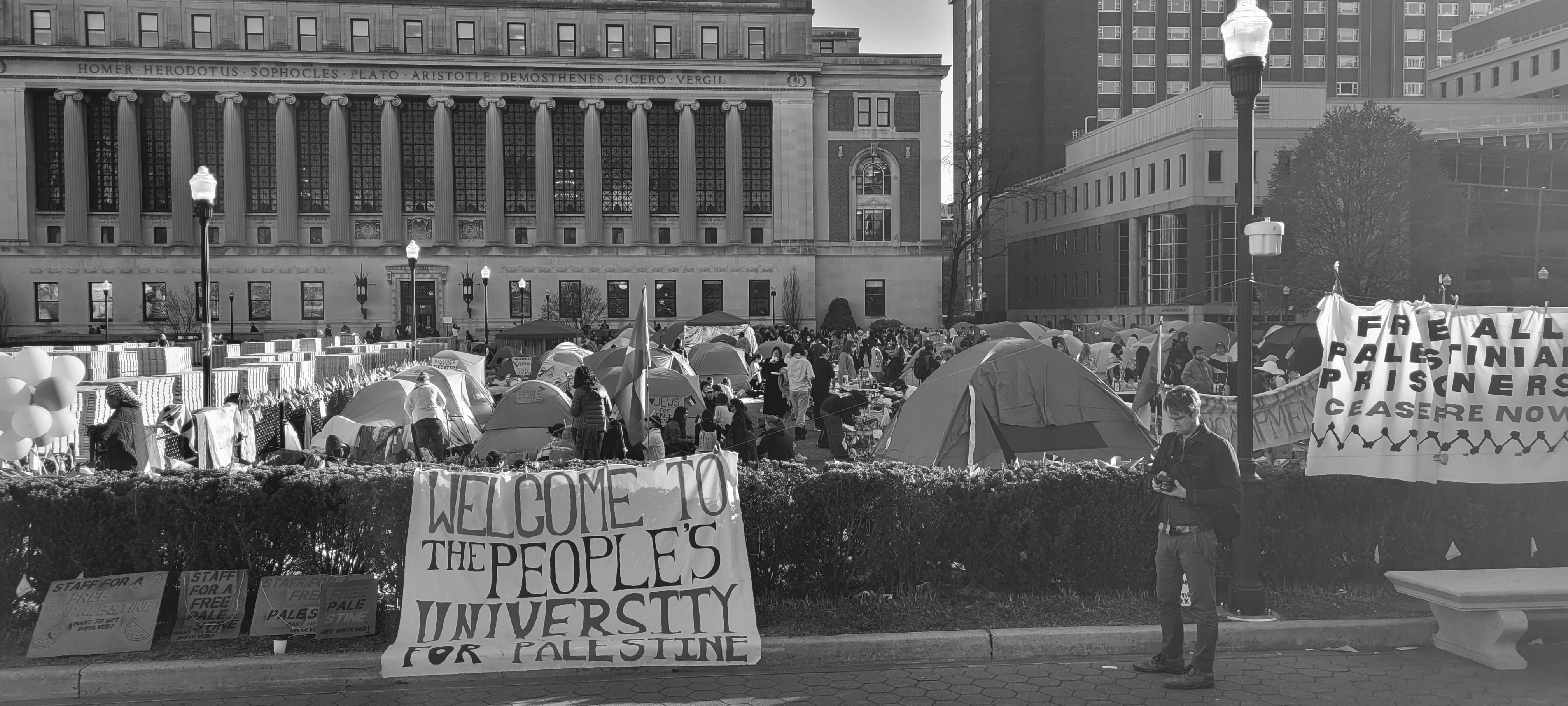

Is there anything more contemptible than an undergraduate? Not if you believe the news. In recent weeks, thousands of students have been arrested, manhandled, banned from campus, evicted from housing, and attacked with rubber bullets, tasers, and chemical irritants at the behest of their own institutional leadership. Mainstream coverage of students protesting the war in Gaza regularly proclaims concern for young people’s well-being, while revealing a clear desire to do them harm. Social-media comment sections are full of impassioned calls to ruin lives for what are, objectively, minor transgressions. Somehow this is not felt to be in contradiction to the overriding imperative of student safety. This style of thought is currently shared by many members of America’s political and economic ruling class, constituting something like a spontaneous ideology that crosses party affiliations. Meanwhile, Israeli forces have destroyed or damaged at least 80 percent of schools in Gaza, prompting experts at the United Nations Human Rights Council to suggest that an intentional “scholasticide” is underway.[footnote UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, “UN Experts Deeply Concerned Over ‘Scholasticide’ in Gaza,” press release, April 18, 2024 →.] Respected news outlets insist that the specter of student-led pogroms on elite campuses is worthier of attention. The anti-student imaginary is full of massacres that aren’t happening, rather than the ones that are.

What accounts for this collective pathology? Or to put it differently: Why does everyone hate college students? In academic as in other counterinsurgencies, it seems that there are times when it becomes necessary to destroy the village in order to save it. To protect students from other students, it is necessary to put a large number of students behind bars. In a fine article entitled “The Campus Does Not Exist,” Samuel P. Catlin points out that the logic of campus security is structured around a fantasy figure that the queer theorist Lee Edelman calls The Child.[footnote Catlin, “The Campus Does Not Exist,” Parapraxis, April 2024 →; Edelman, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive (Duke University Press, 2004).] The Child is not necessarily an actual child; rather, it’s an embodiment of innocence as well as an investment in the (heterosexual) future, even at the expense of people who need help right now. Edelman names this complex “reproductive futurism.” (Another pervasive moral panic that orbits around The Child is the current surge in trans- and homophobia, focused as it is on high school sports and the putative threat of “grooming.”) College students conveniently enter and exit the category of The Child depending on the exigencies of the moment. So do literal children: it is, after all, in the name of the abstract Child that conservatives defend the rights of fetuses even as they eviscerate funding for schools and social programs. But the Republican Party has no monopoly on this libidinal deformation. For the most part, it has been liberal-minded administrators and college presidents bringing down the hammer on campuses.

As Catlin observes, universities present unusually harsh discipline as justified when student-Children are under threat.[footnote Catlin here appropriately cites Jennifer Doyle’s Campus Sex, Campus Security (Semiotext(e), 2015).] Police and administrative violence can be applied to students themselves once they have been stripped of citizenship in the academic state and designated “non-affiliates.” We have seen this happen in the mass arrests at Columbia, NYU, Yale, USC, Emory, UT Austin, Cal State Humboldt, UCLA, and many other institutions. (The list has grown so long that keeping track is difficult.) Catlin argues that this process of recategorizing certain students as “outside” agitators is part and parcel of how both university administrations and the culture at large construct the “campus.” The campus is not so much a physical space as an imaginary one, commonly represented as a site that is forever in crisis. Notions of the crazy, dangerous things that happen on college campuses seem to live rent-free in the minds of many Americans, including, or especially, those who have no direct contact with institutions of advanced learning. Catlin notes that people like to get worked up about protecting Children on Campus even if they happen to be indifferent to students in the flesh.

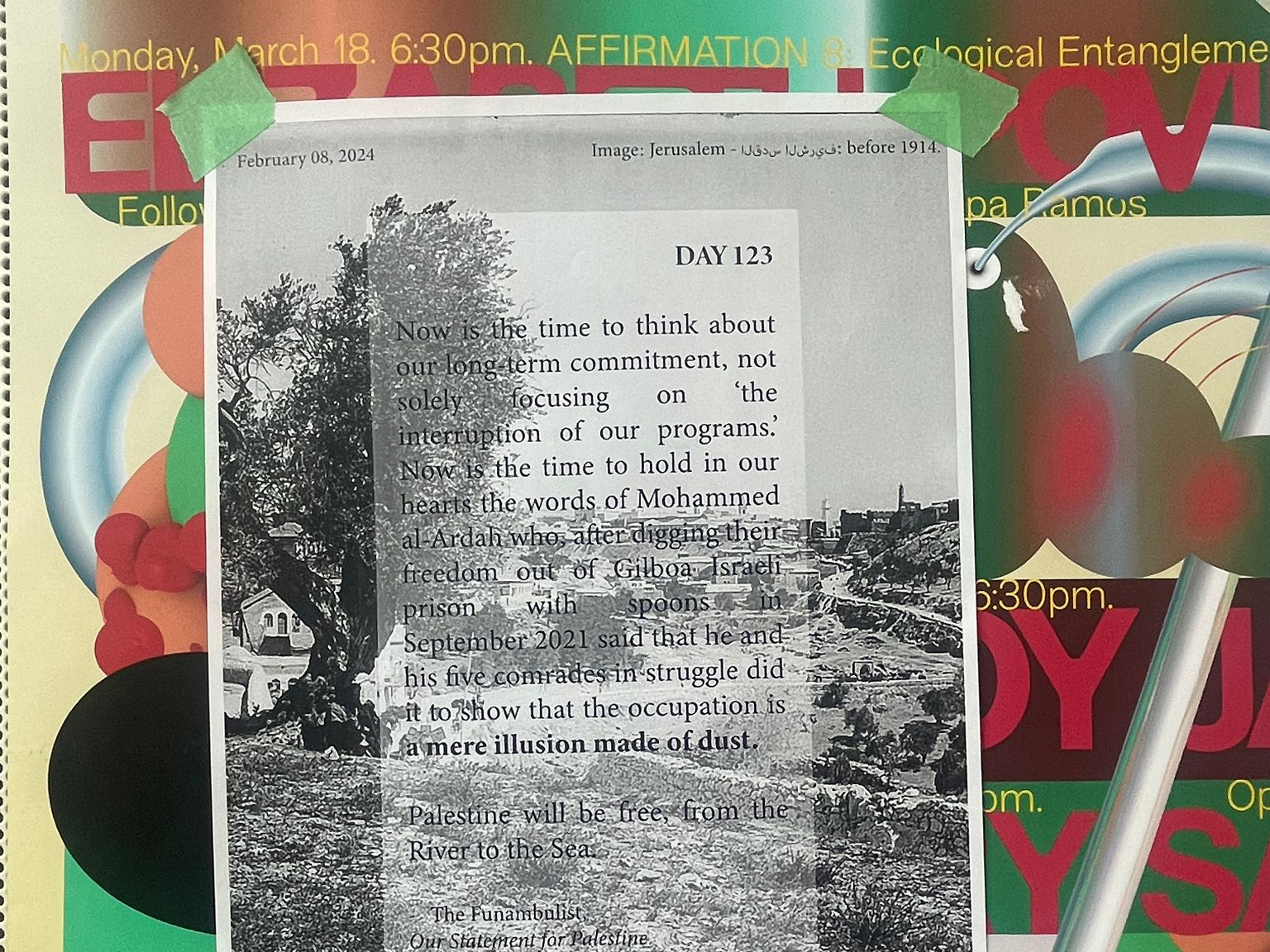

Catlin, however, underemphasizes the reality that sadism directed toward students is a fundamental component of public discourse on higher education. The student is somebody to whom discipline is always rightly forthcoming. Even more so when students are already hateworthy for other reasons: being humanities majors, feminists, queers, critics of colonialism. Even more abhorrent are art students, surely the most frivolous of all. But anti-student sadism generally does not dare speak its name outright. Hence the search for an innocent figure to protect against the disaffiliated student. Jewish people under the threat of antisemitism have been adopted as a new Child, requiring protection at any cost. This scenario—vulnerable Jews under siege—is infantilizing, and, by extension, antisemitic. Invoking antisemitism is a way to enjoy real, potential, or purely hypothetical anti-Jewish violence by concern-trolling about it. We have witnessed congresspeople all but salivate as they ask questions about the supposed genocidal intent of slogans such as “from the river to the sea.” Since these sanguinary visions have little correlation with what protesters say or do, their wellspring seems to be the questioners’ own imaginary. The figure of the student in revolt becomes the vector for the self-proclaimed philosemite’s bloodlust. This student inflicts upon Jews the fantasized violence from which only actual violence can provide protection. It has been said that every accusation is a confession; I wouldn’t put it so categorically, but talk of rampant antisemitism on campus mirrors the logic of Biden’s claim that, without Israel, “there wouldn’t be a Jew in the world that is safe”—a statement that serves as an ostensible warning but rings more as a threat.

It’s moot to speculate how much of this rhetoric is genuine conviction and how much is performance, or whether there is even a difference between the two. There are, of course, powerful material interests that ratify this fantasy. While donor interests might explain the economic and political rationale behind the crackdowns at universities, they do not account for the specific patterns of brutalizing discourse, which seem to be surplus to the demands of capital and the state. Businesses, after all, still need universities to deliver qualified labor power and subsidized research, both of which are under threat from disruption on the scale we have been witnessing. I propose instead that the ferocity of the antagonism must come from the dense overdetermination of higher education’s role in class reproduction.

First: it ought to be self-evident that the paradigmatic function of universities is to reproduce class. Until recently, the point of the Ivy League was simply to produce Ivy League graduates who could serve as a prefabricated (wealthy, white, Christian) ruling elite. Whatever knowledge students obtained along the way was essentially decorative. In recent decades, this function has partly broken down as degrees have become little more than a sorting mechanism—even at the lower end of the labor market—rather than a ticket into the bourgeoisie. While Ivy League universities retain their class-reproducing function to a greater extent than other schools, the ongoing diversification of student bodies countrywide (including a growing number of people from working-class backgrounds) has scrambled ideas of what exactly a student is. No longer automatically a wealthy, white, Anglo-Saxon Protestant, the Ivy League student is now many things at once: privileged brat, liberal arts major turned barista, future finance bro, precocious tech entrepreneur, preppy legacy dullard, affirmative action fraud, dupe of tenured radicals, coddled baby, violent militant. This is what a discourse of class looks like in ruins.

Some of these valences of the Student do connote class superiority; when these are made the targets of anti-student zeal, the fantasy is one of revenge. But the modality in which one imagines revenge converges with the Student’s other incompatible roles in at least one key way. The Student is preeminently a subject of discipline. Arrogant snowflakes meet the real world, where facts don’t care about your feelings; would-be radicals get job offers rescinded; would-be gender theorists get their dignity stripped in low-paying service jobs. In all of these scenes, a real insight into the falling value of advanced education in the labor market is articulated as schadenfreude, with boss or dean serving as avenging angel. In this respect, administrative and police violence, in concert with labor discipline, produces the real unity of an otherwise incoherent category. I would suggest that the figure of the student in current discourse is not a set of empirical characteristics; —rather, it is defined by susceptibility to discipline. A student is a person to whom an expanded range of disciplinary procedures can be applied, since they are at the mercy of multiple sovereignties. Thus, students can be simultaneously arrested by the NYPD, evicted from their homes, and suspended from academic programs. And in Gaza, they are being killed.

There is nothing all that unique about the discipline to which students are exposed. Outside campus gates, non-graduates and the working poor face arbitrary power in even more naked forms. But off-campus violence is naturalized by economic and governmental rationalities in different ways. Here, the “mute compulsion” of economic relations limits the moral responsibility of individual actors, including bosses themselves.[footnote The phrase “mute compulsion” is Karl Marx’s. Søren Mau has recently brought it back to attention in his book Mute Compulsion: A Marxist Theory of the Economic Power of Capital (Verso, 2023).] Getting fired may ruin your life, but that’s just the economy, stupid. At the same time, police and the legal apparatus directly coerce and punish. Despite being unambiguous manifestations of state power, police and the law nevertheless appear as the de facto forms of violence through which any bourgeois society controls its underclass; there is nothing shocking about a poor person getting arrested or getting shot, and accordingly, nothing like the same attention is paid to such events compared to happenings on the mythic Campus. To those on the receiving end of economic exploitation and state repression, the student’s position is enviable indeed.

What accounts for this distinction is that the student is seen as a future worker, or a potential future member of the reserve army of labor—even if, empirically speaking, a large percentage students work their way through college, and that ostensible future is increasingly a vanishing one.[footnote The growing unlikelihood that today’s students will ever get to join the ranks of the middle class is the main fact that has to be appended to a text that otherwise remains exemplary, the pamphlet On the Poverty of Student Life (published by the Situationist International and students of the University of Strasbourg in 1966; Mustapha Khayati was the principle author).] The myriad ways in which students feed into capital accumulation are not directly visible, since, qua students, students are not exploited. In this sense, their activities are perceived as analogous to other kinds of “unproductive,” unwaged labor, such as housework. This is to put things in categorical terms that do not necessarily correspond to reality. Graduate students, for one thing, are often clearly workers (as teaching and research assistants), and successfully organize as such. But “worker” and “student” are at least notionally meant to exclude each other.

The campus thus appears to be a zone in which economic necessity is suspended. A corollary is that violence against students appears to be divorced from the “normal” repression of proletarians. To witness the spectacle of anti-student discipline is to see the force of pure sovereignty, stripped of its economic naturalization. The student is the torsion point at which the mute compulsion of capitalist social relations meets Louis Althusser’s two state apparatuses: the “ideological state apparatus” that reproduces labor power, and the “repressive state apparatus” that metes out discipline and punishment. That students apparently have nothing more useful to do than to learn (or, heaven forbid, make art) is a source of envy, admiration, and resentment, some of it merited, since the quarantining of students from everybody else is part of class society’s logic of separation. But resentment from on high is never merited in the slightest.

Graffiti written on the walls of a classroom at the University of Lyon, 1968. Students occupied portions of the campus during widespread protests, demonstrations, and strikes across France in May and June of that year. Photo: George Garrigues.

A proper contextualization of the current campus protests should not only slot them into the legacy of previous student movements (for which the mythos of “the sixties” is now set in stone). It should also tie them to other recent episodes of mass social unrest in the United States, such as the uprisings for Black lives in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014, and then across the nation after the murder of George Floyd in 2020. During the Black Lives Matter protests, relations between segments of the college-educated but downwardly mobile middle class and racialized proletarians became acutely problematized. Two symmetrical but contradictory representations of these events proliferated across traditional and social media alike. On the one hand, the poor and people of color were subject to a familiar and often blatantly racist rhetoric of feral lawlessness. On the other hand, educated and largely white “riot tourists,” who dared to betray their race and class by performing material acts of solidarity with the insurgents, found themselves called out for supposed hypocrisy, often by liberals and even leftists. The question of what actions other than pointless virtue signaling or grindingly slow institutional reform might be permissible for the “graduate without a future,” a term coined during another cycle of global revolt,[footnote Paul Mason, “The Graduate Without a Future,” The Guardian, July 1, 2012.] was left unanswered. A solution wasn’t found, of course. In any case, despite great efforts made by Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion bureaucrats to roll out new “woke” capitalism within academia, the most important instances of unity happened not in the seminar room or corporate office but in the streets, where shared outrage at the police occasionally bridged real and persistent inequalities between different camps of demonstrators.

These moments of collective action may have been just as chimerical as the cross-class alliances of older proto-revolutionary sequences, such as when French lycéens steeped in Lacan and Mao’s Little Red Book descended to the factories in the 1970s. There is something inherently absurd about these scenes: students who play revolutionaries always seem to wear an ill-fitting costume, even when their revolutions are quite real. Yet something of this sort remains at the horizon of any student movement that has the potential to transcend the hoary rituals of campus protest. There is a chance that pro-Palestinian students, recognizing the treason of their elders (university presidents, police chiefs, and far too many professors), will ally their specific grievances with a more totalizing proletarian critique of the educational system’s function as an engine of class dominance.[footnote This may be happening. As I write, graduate students in the University of California system have just voted to authorize a strike in protest of rights violations during recent demonstrations.] To the advantage of our ruling class, this critique too often tends to be conflated with reactionary anti-student propaganda that fills the airwaves with horror stories about the American youth wing of Hamas. To put it succinctly, poor people hate students for good reasons whereas rich people hate them for bad reasons. Is it possible to disentangle the rational hatred of the poor from the irrational hatred of the rich? Not in words. But the history of revolutionary movements is a history of attempts—often failed—to unify various groups, in practice more than in theory: peasants and soldiers in 1917, workers and students in 1968.

A previous version of this piece appeared on Substack.

UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, “UN Experts Deeply Concerned Over ‘Scholasticide’ in Gaza,” press release, April 18, 2024 →.

Catlin, “The Campus Does Not Exist,” Parapraxis, April 2024 →; Edelman, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive (Duke University Press, 2004).

Catlin here appropriately cites Jennifer Doyle’s Campus Sex, Campus Security (Semiotext(e), 2015).

The phrase “mute compulsion” is Karl Marx’s. Søren Mau has recently brought it back to attention in his book Mute Compulsion: A Marxist Theory of the Economic Power of Capital (Verso, 2023).

The growing unlikelihood that today’s students will ever get to join the ranks of the middle class is the main fact that has to be appended to a text that otherwise remains exemplary, the pamphlet On the Poverty of Student Life (published by the Situationist International and students of the University of Strasbourg in 1966; Mustapha Khayati was the principle author).

Paul Mason, “The Graduate Without a Future,” The Guardian, July 1, 2012.

This may be happening. As I write, graduate students in the University of California system have just voted to authorize a strike in protest of rights violations during recent demonstrations.