With the start of the fall semester, many are wondering what’s next for rattled but energized student activists. Over the summer, at least 100 universities put in place new ordinances to impede, prevent, or discipline protests. Some solicited the services of the “risk and crisis management consulting industry” to usher in a tighter securitization regime, as detailed in a new report from Mondoweiss.1 Earlier this year, Columbia University served as a cradle of pro-Palestine student movements, while the administration’s response provided a model for other universities’ recriminations in turn: in a now familiar sequence of events, pro-Palestinian students were doxxed and faced a chemical attack while the Columbia chapters of two advocacy organizations, Jewish Voice for Peace and Students for Justice in Palestine, were banned from the school. Protestors mounted an encampment on the school’s south lawn, which sparked a movement that spread to around 150 other colleges and universities in the country and a handful more abroad. Participating students faced targeted harassment, got kicked out of housing, were suspended and threatened with expulsion. The school hired a private investigator to visit student activists’ residences in at least two instances.2 Donors flexed, threatening to withhold millions from the school. Columbia’s now-resigned president Minouche Shafik solicited the NYPD to come onto campus, sweep the encampment, and arrest over 150 of her own students.3 At least seventy-two other schools followed her lead.4

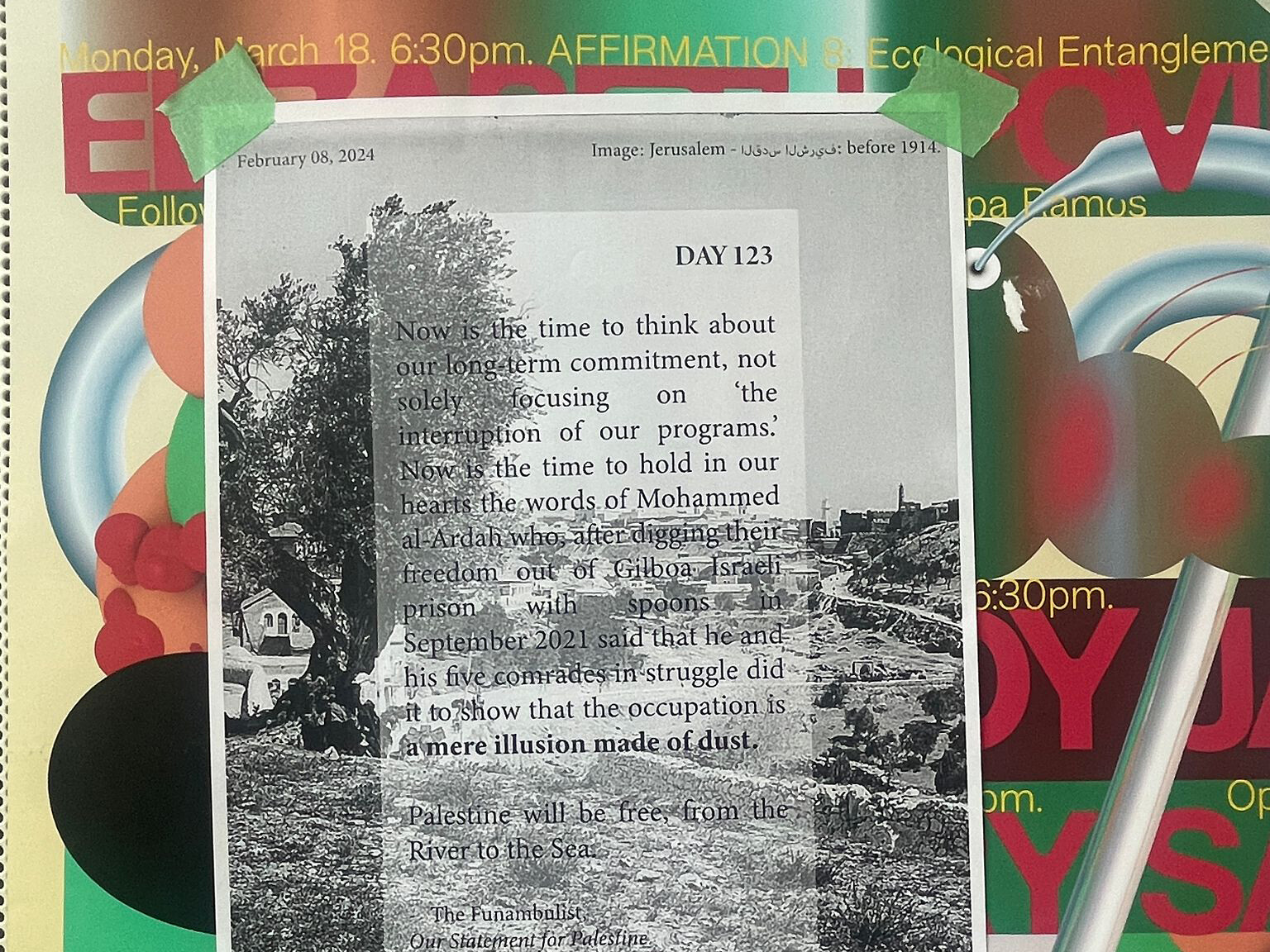

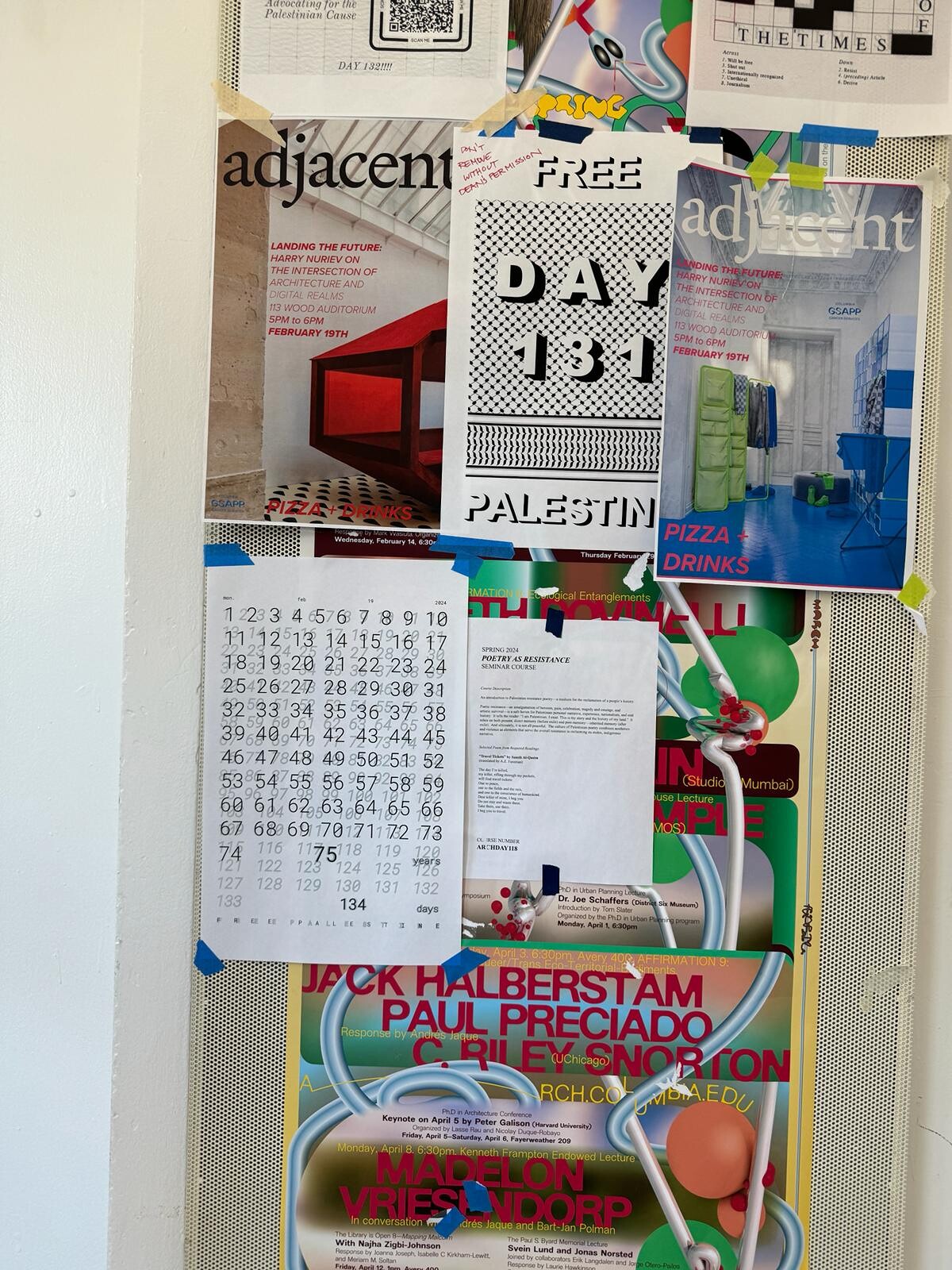

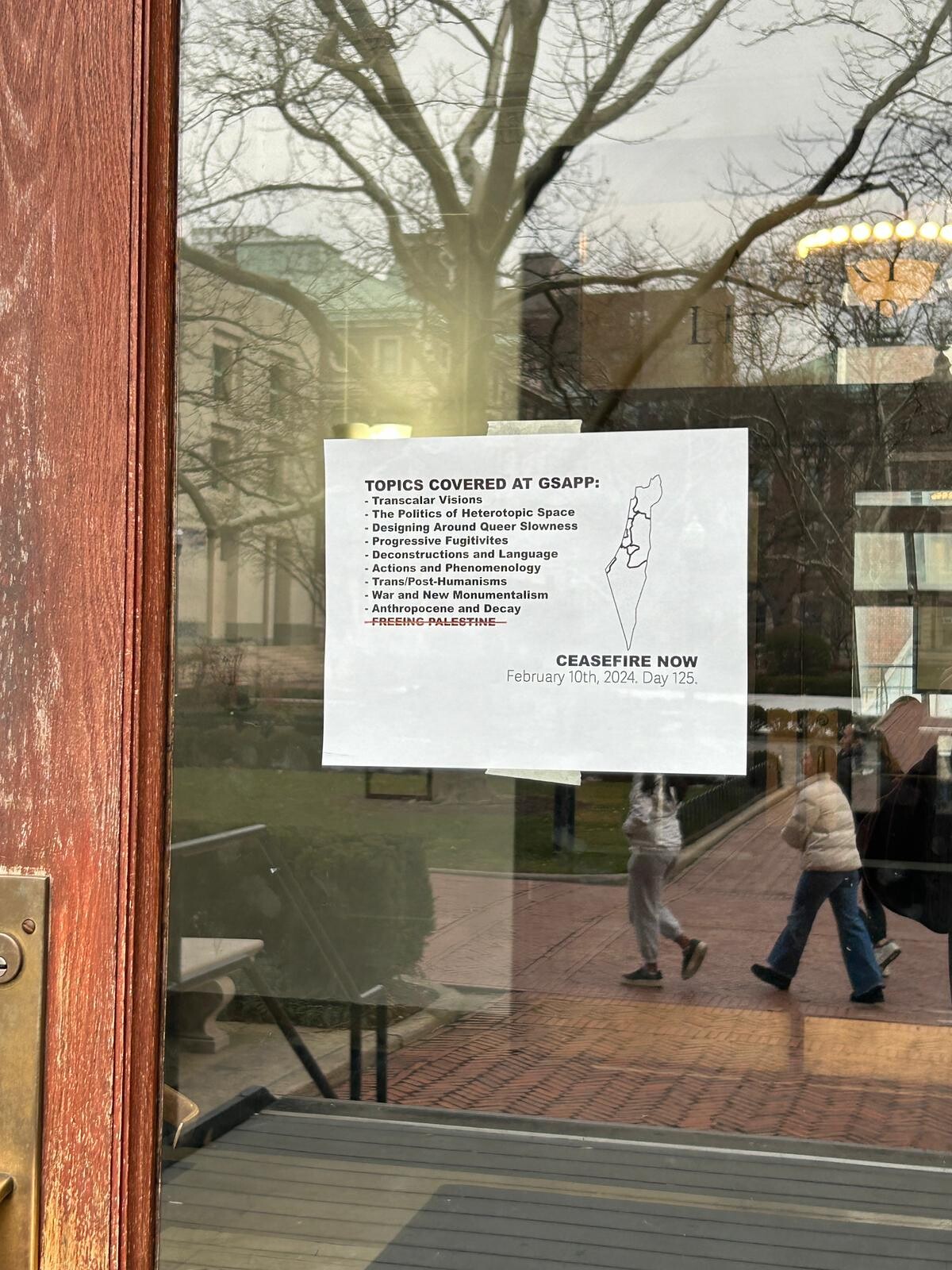

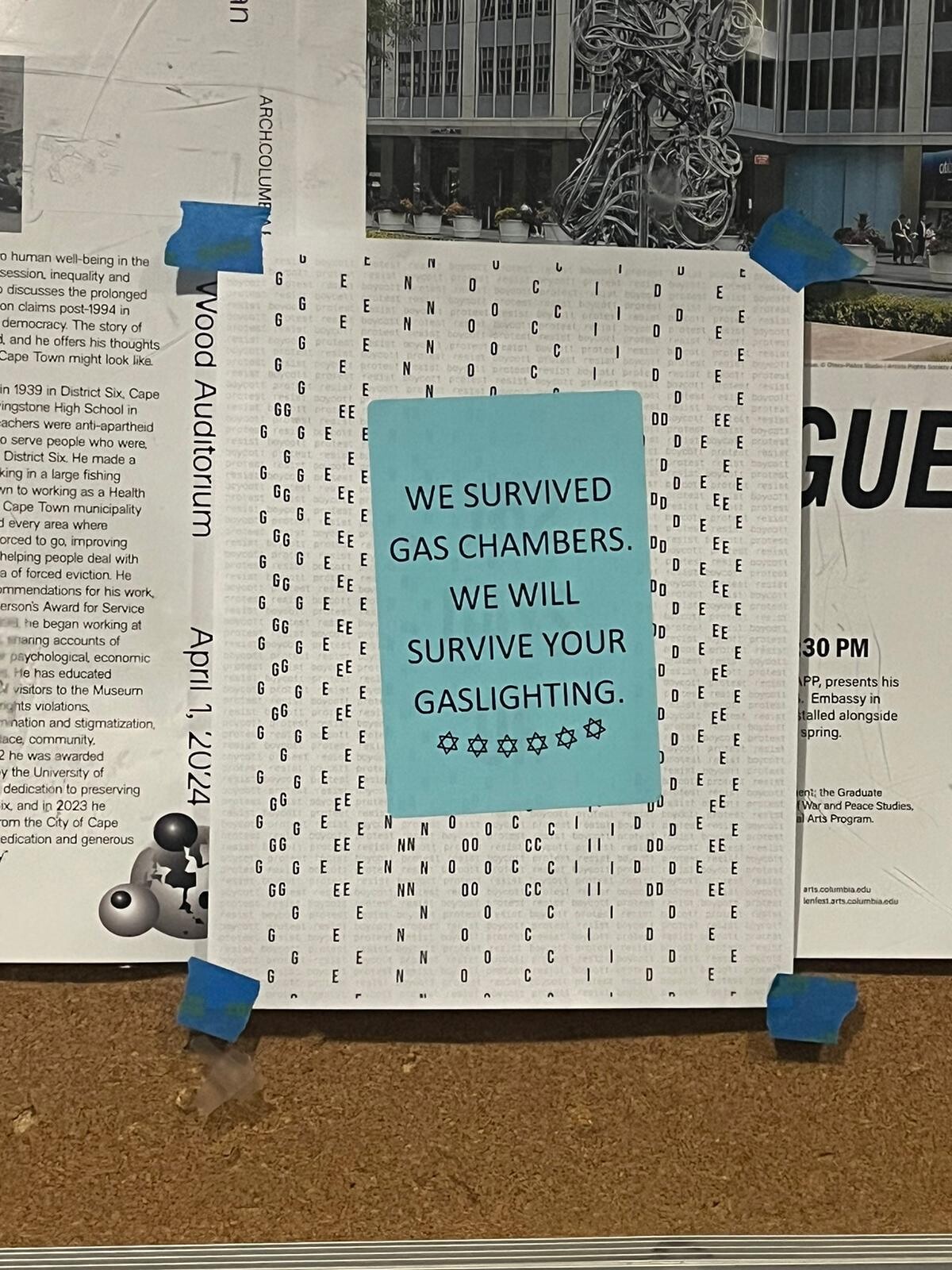

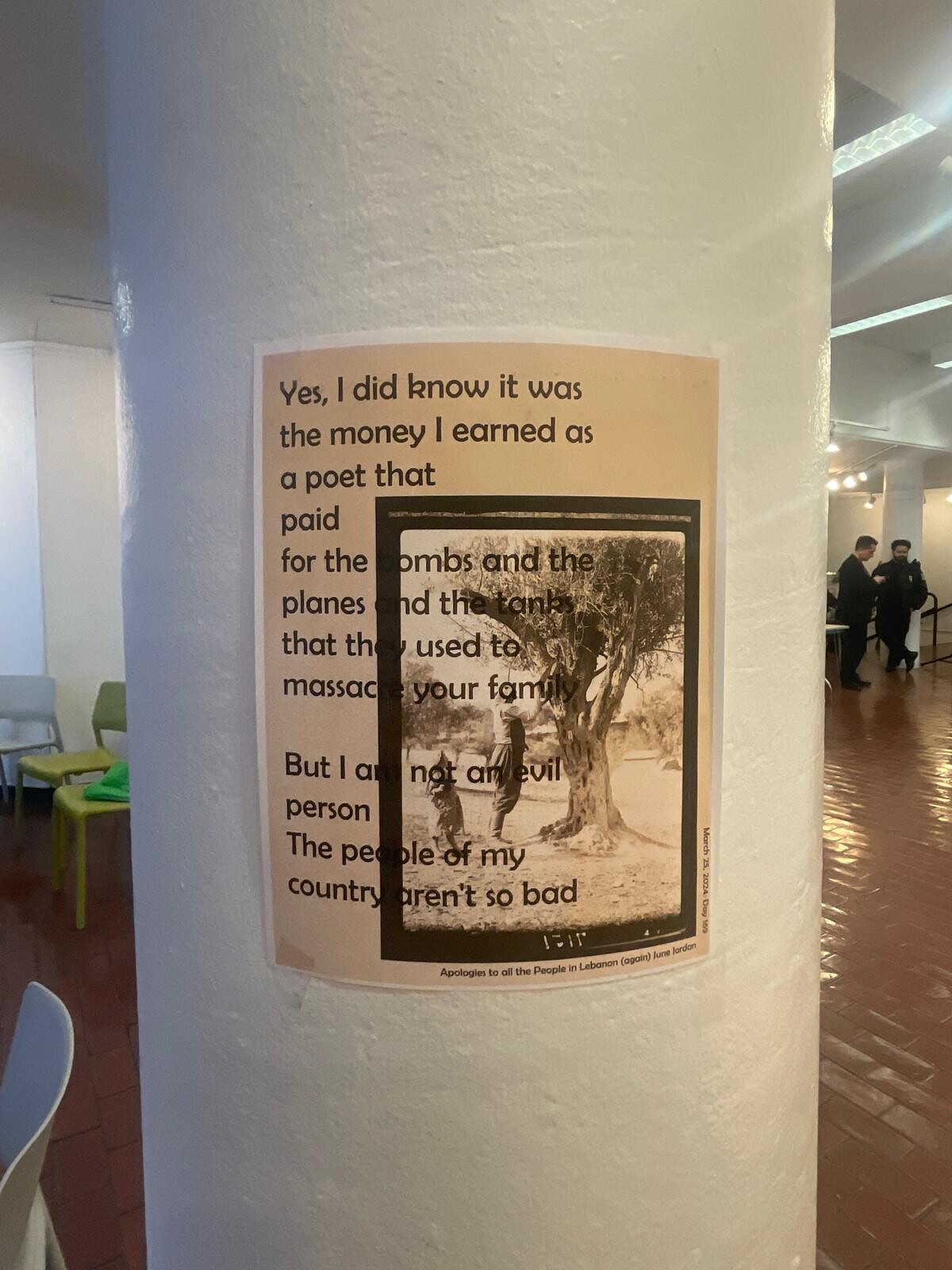

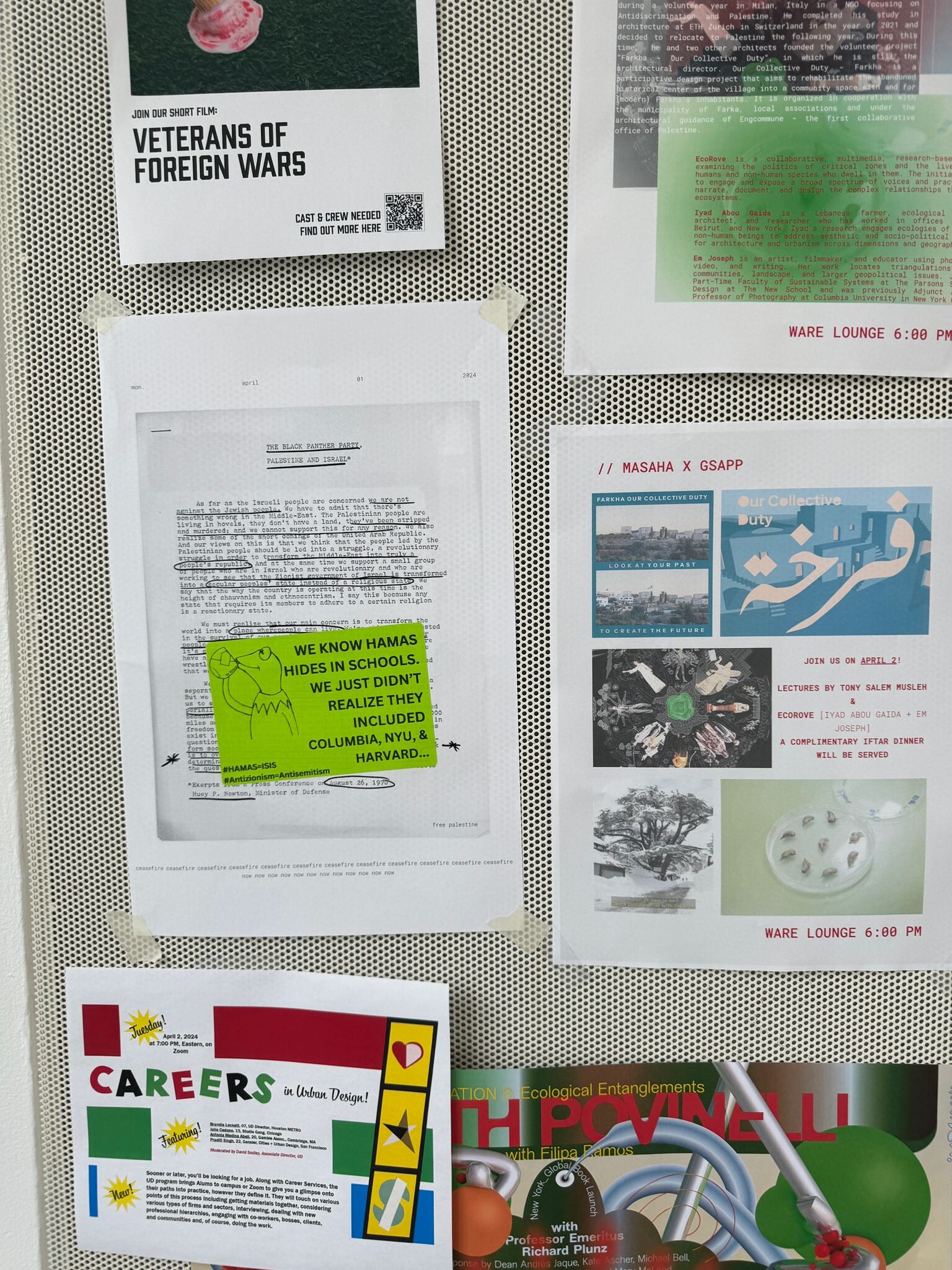

A new coalition, Columbia University Apartheid Divest (CUAD), has emerged to mobilize around five demands, including financial divestment from Israel.5 Molecular, program-specific initiatives have also surfaced in the wake of the campus protest movement, which brings us to the Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation (GSAPP). After the chemical attack in late January, an anonymous collective of architecture students calling themselves the secret poster club (spc) began hanging small printed posters around department buildings—in stairwells and hallways, and on bulletin boards. Some featured quotations by Palestinian writers, including Refaat Alareer, Mahmoud Darwish, Edward Said, Mosab Abu Toha, and Mary Turfah, and Black radicals like Angela Davis, June Jordan, and Audre Lorde. Many read “CEASEFIRE NOW,” which dates the posters to a time before, as Adam Johnson recently remarked, “activists shifted their key demand from a ceasefire to an arms embargo on Israel” in response to the White House’s cooptation of the term “ceasefire,” rendering it toothless.6 Many of the posters serve a timekeeping function by displaying the number of days since Israel began its onslaught. Despite hanging the posters in communal areas where students are permitted to display printed materials, students in support of Israel began tearing down the posters or covering them up with stickers bearing Zionist slogans. Soon, at the direction of school administrators, facilities workers began removing the posters as well.

The effaced, crumpled, and trashed posters are archived on spc’s own website in a section titled “Traces,” which amounts to an evocative repository of an asynchronous, silent, sedimented political dispute. The site displays an impressive quantity and variety of posters, reflecting an output that was designed to counteract the material’s ephemerality. That each poster would only last anywhere from an hour to a couple days changed spc’s design calculus: they hung posters in unorthodox places, created designs that mimicked other departmental materials, sought out the endorsement of the Student Workers of Columbia to provide more legitimacy (the posters still came down), and shrunk their political content so that it would only be legible upon closer viewing. At first glance, one poster resembles a calendar—but the numbers go all the way up to seventy-five, referring to the years since the Nakba. Another mimics the user interface of dimensions.com, an online database of dimensioned drawings used in student projects. The poster proposes an entry for Benjamin Netanyahu with text reading “a genocidal maniac and the longest tenured prime minister of Israel. With a degree in architecture from MIT, Netanyahu understands how formative our field is to the project of settler colonialism.”7 A poster reading “A Field Manual for Starving a Population: A Collaborative Guide by the U.S. and Israeli Government” could feasibly be confused for promotional material for a book talk.

From the secret poster club’s “Traces” archive. Courtesy of the secret poster club.

From the secret poster club’s “Traces” archive. Courtesy of the secret poster club.

From the secret poster club’s “Traces” archive. Courtesy of the secret poster club.

From the secret poster club’s “Traces” archive. Courtesy of the secret poster club.

From the secret poster club’s “Traces” archive. Courtesy of the secret poster club.

From the secret poster club’s “Traces” archive. Courtesy of the secret poster club.

When I asked a spc member about the climate within GSAPP during the spring protests, they said, “Watching the campus events unfold created an environment of fear. Seeing student protestors be accused of being antisemitic, doxxed, suspended, evicted, and threatened with expulsion made us all afraid of what would happen if administration or other students found out who was behind the posters. secret poster club grew out of the desire to create space for engaging with the student protest movement on campus, as well as Palestinian struggles for liberation made us want to make posters and stand in solidarity with each other.” Dean Jaque hosted a town hall to discuss the protests, but did not utter the word “Palestine.” spc participants have a nuanced understanding of this culture of muteness: they know that adjunct professors are muzzled by their relative precarity within the school, and how vicious the punishments meted out for Palestinian advocacy are.

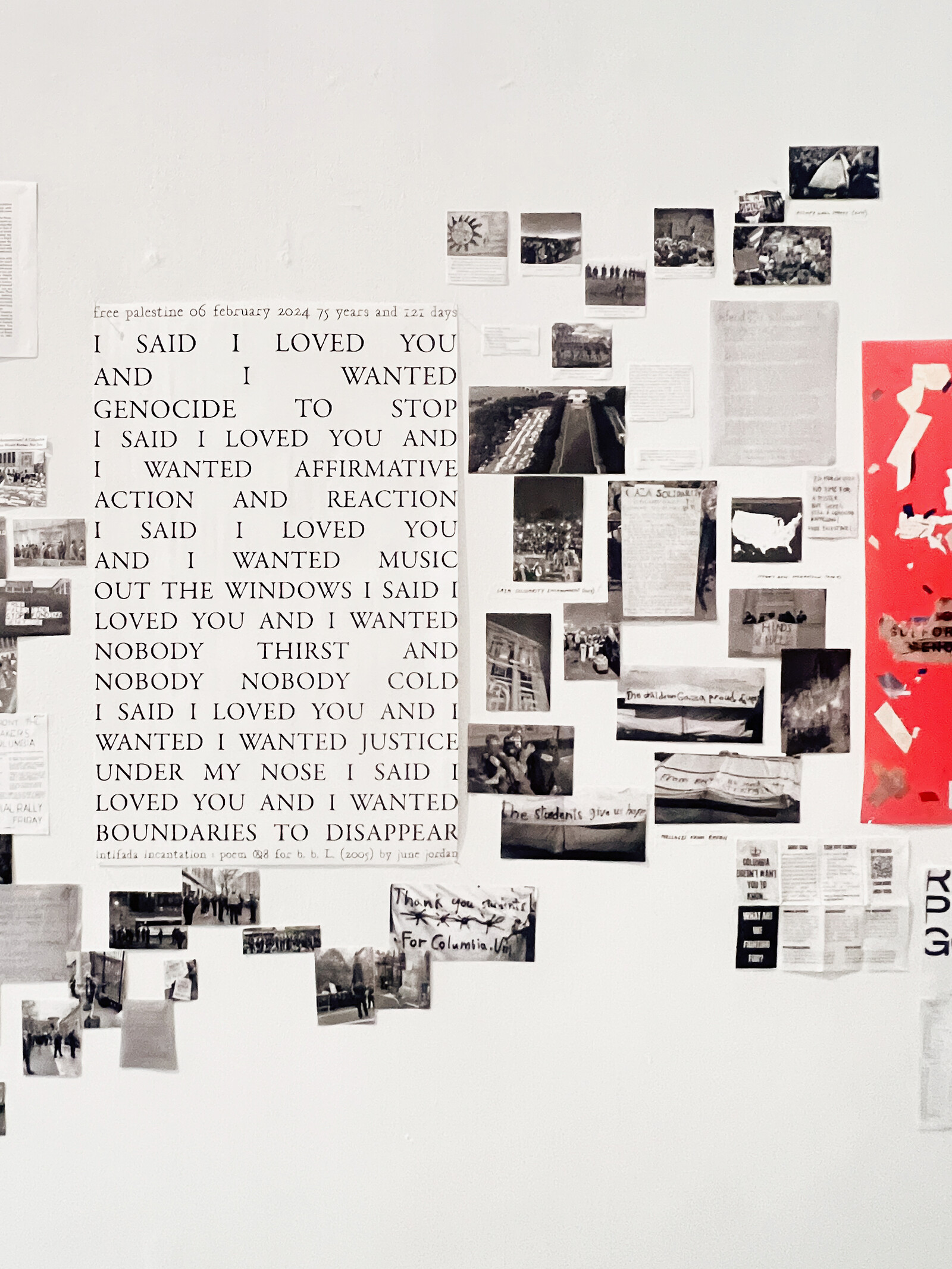

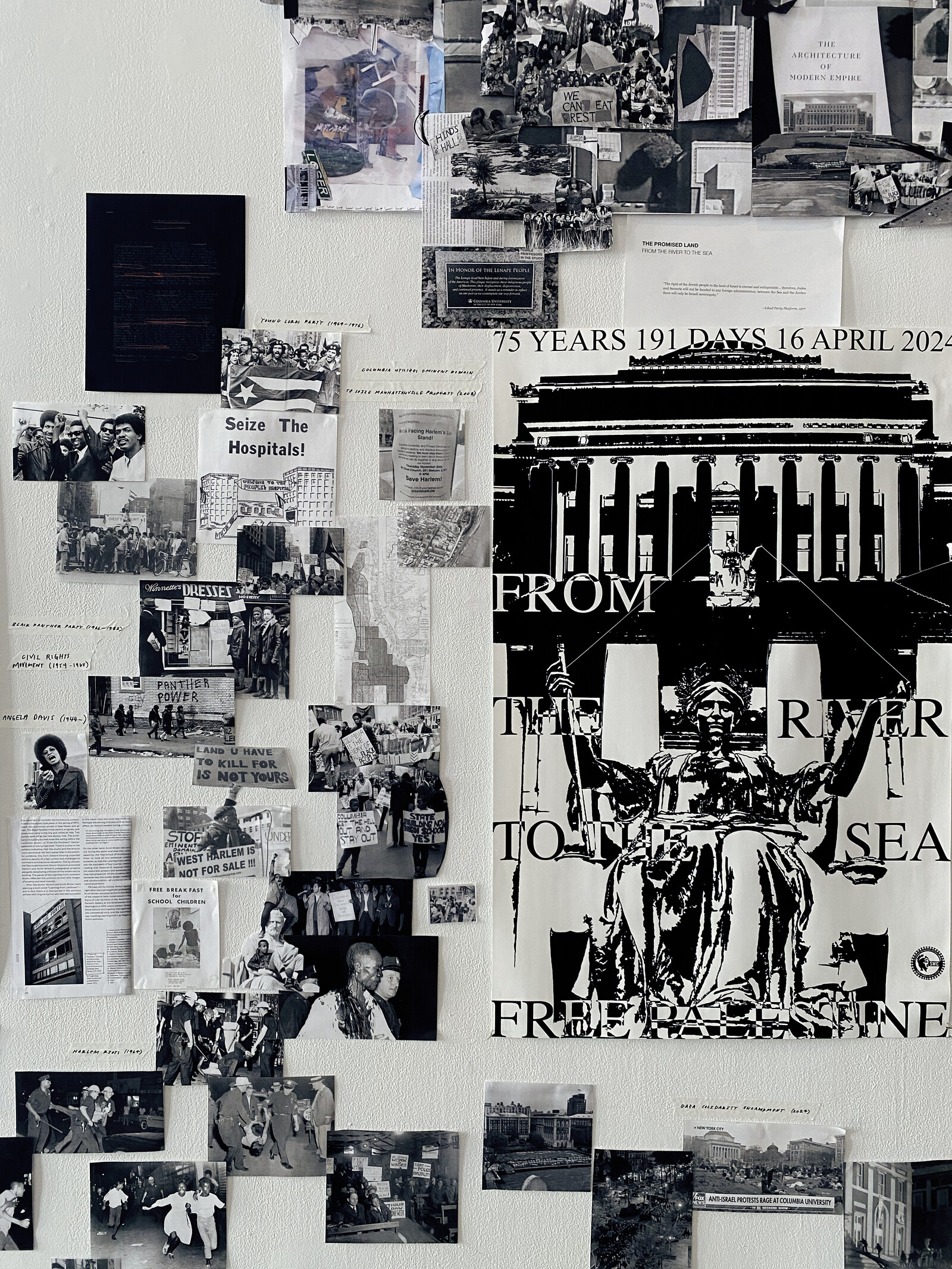

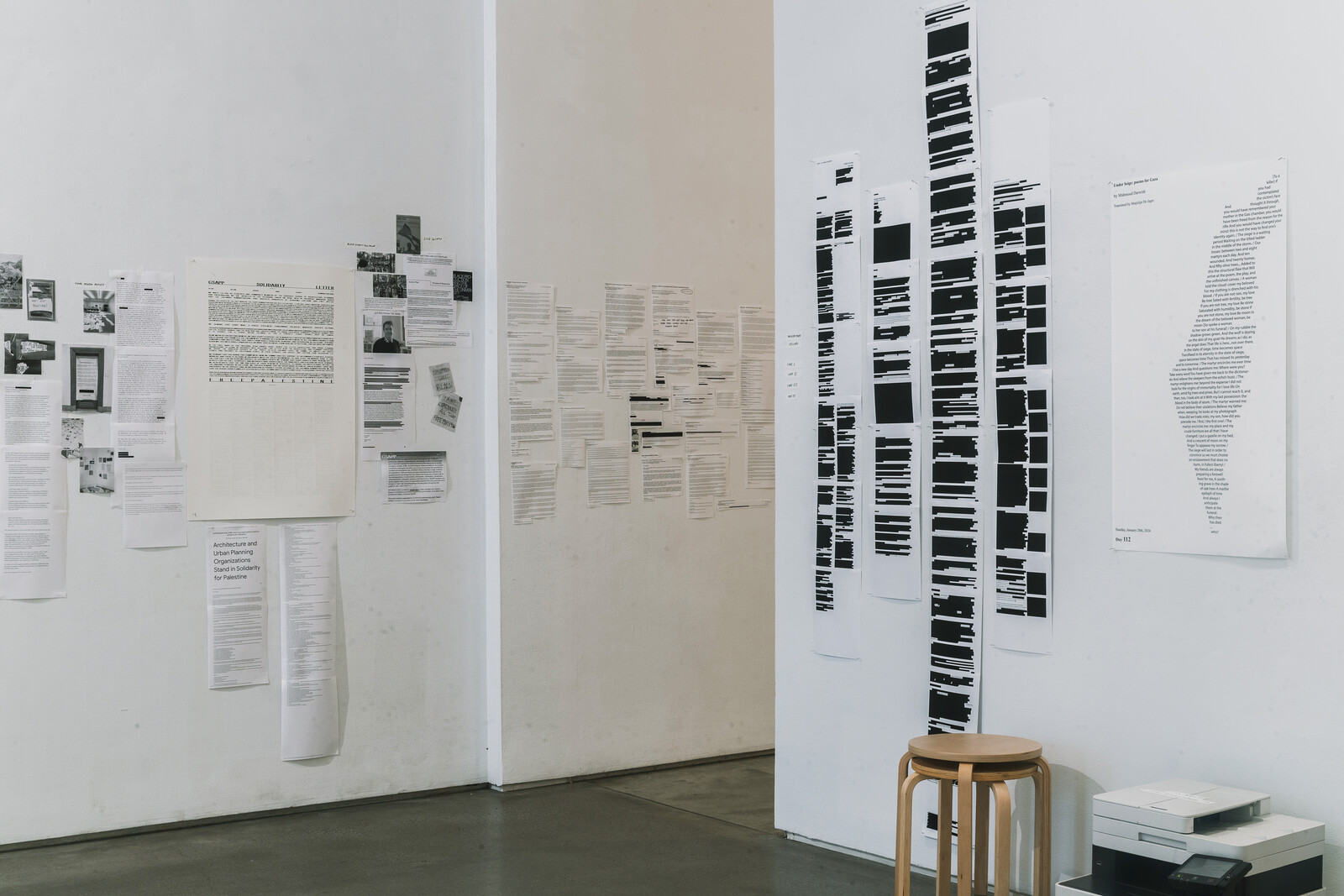

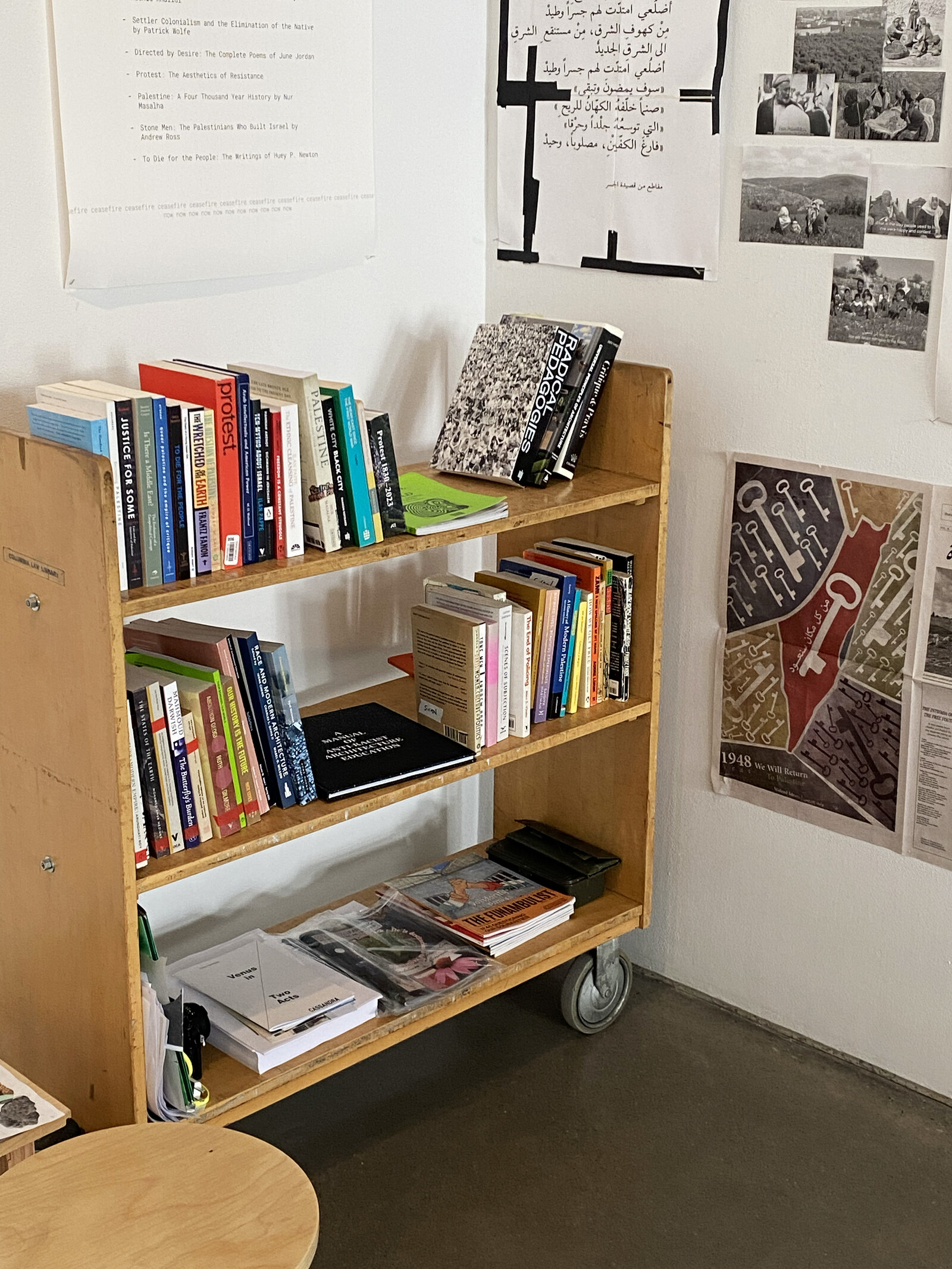

Typically, each GSAPP semester culminates in an exhibition of student work, but since university administrators shut down campus buildings, the showcase moved online. spc members felt it grotesque to celebrate their projects amid suppression on campus and genocide abroad. They instead sought an offsite venue—a83 Gallery in SoHo—to exhibit the posters, along with other research and documentation relating to the occupation, now protected from the threat of imminent removal. The exhibition, which ran from August 16 to September 8, was titled what is a school?, posing a simple question that conferred both the students’ disappointment with the debased form of the actual university and their belief in education as an ideal. They hosted workshops led by architects, designers, and activists, on topics including the relationship between architecture and settler colonialism; the possibility of a solidaristic architecture discipline; the meaning of “pessoptimism,” a term coined by Palestinian writer Emile Habibi; June Jordan’s speculative “collaborative architectural redesign of Harlem”; and an anti-imperial critique of Columbia University’s architectural syntax.8 Through this programming, spc members attempt to advance a critical, at times insurgent architectural discourse that has bloomed over the past few decades to critique the complicity of the architectural field, and to diagram the real architectural machinations of the Israeli occupation—itself instantiated as an interlinked network of checkpoints, prisons, partitions, gates, settlements, turnstiles, turrets, and camps.9

It was GSAPP’s affinity for these very discourses that initially drew spc members to the department. In addition to hosting or employing some of the aforementioned figures, GSAPP has convened discussions about Black-Palestinian solidarity, apartheid in Palestine, settler colonialism, the architecture of refugee camps, the right to asylum, and the role of Palestinian labor in the construction of Israel.10 During the wave of pro-Palestinian activism that corresponded with Israel’s 2021 military aggression against Gaza, GSAPP dean Andrés Jaque signed an open-letter statement of solidarity titled “Architecture and urban planning organizations stand in solidarity for Palestine” along with seven other faculty members and two organizations, the Black Student Alliance and Faculty of the PhD Program in Architecture.11 Seven GSAPP faculty also signed the Letter Against Apartheid that circulated around the same time.12 Themes such as displacement, anti-racism, and colonialism recur in seminars. In response, what is a school? features, according to one spc member, “redacted versions of the core architecture studio syllabi, seeking to highlight the disconnection between GSAPP’s pedagogy and practice.” This exemplifies a broader posture of institutional critique within the exhibition, and spc’s production in general: One poster reads “Topics Covered at GSAPP: Transcalar Visions, The Politics of Heterotopic Space, Designing Around Queer Slowness, Progressive Fugitivities, Deconstructions and Language, Actions and Phenomenology, Trans/Post-Humanisms, War and New Monumentalism, Anthropocene and Decay, FREEING PALESTINE”. This poster indicts both the department for its silence and the curriculum for instrumentalizing various theoretical discourses derived from twentieth century continental philosophy—many originally formulated with a sort of liberatory telos.

View of the secret poster club’s exhibition “what is a school?,” a83 Gallery, New York, 2024. Photo: Omer Gorashi.

Detail view of the secret poster club’s exhibition “what is a school?,” a83 Gallery, New York, 2024. Photo: Omer Gorashi.

View of the secret poster club’s exhibition “what is a school?,” a83 Gallery, New York, 2024. Photo: Omer Gorashi.

Detail view of the secret poster club’s exhibition “what is a school?,” a83 Gallery, New York, 2024. Courtesy of the secret poster club.

View of the secret poster club’s exhibition “what is a school?,” a83 Gallery, New York, 2024. Photo: Omer Gorashi.

Detail view of the secret poster club’s exhibition “what is a school?,” a83 Gallery, New York, 2024. Courtesy of the secret poster club.

View of the secret poster club’s exhibition “what is a school?,” a83 Gallery, New York, 2024. Photo: Omer Gorashi.

View of the secret poster club’s exhibition “what is a school?,” a83 Gallery, New York, 2024. Photo: Omer Gorashi.

In her 2022 essay on the museum protests, Rachel Hunter Himes writes that today’s organizing terrain is characterized by an “almost total lack of strategic pressure points from which to attack an ironclad and unimpeachable oligarchy.”13 This year, an Ivy League university re-emerged as one such pressure point. The rate and scale at which the encampments multiplied was breathtaking. The students were able to hijack its espoused commitment to dialogism and reveal it to be a veneer masking an institution embedded in global processes of dispossession. secret poster club, through their specialized training in architecture and design and their interest in radical pedagogy, attempt to map these processes, for instance, through a spiral timeline in graphite on the wall of the gallery that plots moments of contact and collaboration between Columbia University and Israel. These types of interventions offer a compelling framing of activism as a design problem. Now is, as ever, a time for political experimentation, because the Palestinian solidarity movement has not yet succeeded in stopping the carnage—the genocide in Gaza shows no signs of abating, and the events of the past few days suggest that Israel may be on the brink of war with Lebanon. The public is confronted with symbols, discourses, images, and information about these events in a highly mediated, disordered, affectively loaded context; this material is in dire need of organization into a coherent message about the ongoing emergency. spc strives to do just that.

However, for the most part, spc conveys information, not messages. This is because they have inevitably found themselves facing challenging, irreducibly political questions that transcend design problems. If they wish to continue, these factors will become unavoidable. These questions are not altogether different from those faced by campus activists in the 1960s and ’70s. Student activists must address whether or not the fact that universities are complicit in American imperialist wars of aggression also makes them significant sites for political struggle. They also need to ask how left-wing social movements in the United States can enact a genuinely internationalist politics with the victims of American militarism abroad.14 The spc members I spoke to strike me as intelligent, courageous, motivated, well-intentioned, and slightly green as political thinkers. Perhaps this reflects a broader aporia: as Sami Khatib recently wrote, the post-Cold War human rights paradigm for narrating global violence occludes political antagonism as such. We can recognize humanitarian victims, and we can condemn “terrorism,” but legitimate political resistance on the part of subjugated populations is not really acknowledged as possible, especially not for Palestinians.15 As spc has revealed, this is at best a conspicuous blind spot on GSAPP syllabus, and at worst a form of censorship.

That said, however impressive and thoughtful spc’s exhibition was, I remain ambivalent about their decision to move their activism off campus, although I understand this exhibition is only one instantiation of a larger ongoing project that will hopefully return to Columbia as classes and protests resume. Staging the exhibition in SoHo reads as an exit from a site of real political contestation into a space that is aesthetically sumptuous, cerebral, and aseptic. Columbia’s refusal to let their posters hang, however demoralizing, signals to me that spc is bumping up against something real, which is why I regard the residue of the torn posters—both in the halls of GSAPP and archived through photographs—as a more radical presentation than the exhibition. While spc says that they would not exist without CUAD and the broader campus movement, spc seems to want to carve out its own discursive space with relative autonomy and—dare I say—a more professional gloss. They would do better to hew closer, not further away, from political organizations, so that those swayed by their guerrilla design work can be directed into a movement. If they continue only as an exhibition collective, their presentations will quickly turn into mausoleums for their own good intentions.

Tovia Smith, “With a new semester, colleges brace for more antiwar protests from students,” npr, August 12, 2024, →; Carrie Zaremba, “U.S. universities spent the summer strategizing to suppress student activism. Here is their plan.,” Mondoweiss, September 2, 2024, →.; Sophie Hurwitz, “New University Rules Crack Down on Gaza Protests,” Mother Jones, September 13, 2024, →.

As Columbia law professor David Pozen maps in his essay “Seeing the University More Clearly,” Shafik’s capacity to unilaterally sic the police on students was the culmination of a more than a decade of consolidation of executive power within the university. See: David Pozen, “Seeing the University More Clearly,” Balkinization, May 6, 2024, →.

The New York Times, “Where Protesters on U.S. Campuses Have Been Arrested or Detained,” The New York Times, July 22, 2024, →.

About Columbia University Apartheid Divest,” Columbia University Apartheid Divest, accessed September 9, 2024, →.

Adam Johnson, “Celebrating at the DNC in a Time of Genocide” The Nation, August 23, 2024, →.

“Posters,” secret poster club, accessed September 9, 2024, →.

Claire Schwartz, “When June Jordan and Buckminster Fuller Tried to Redesign Harlem,” The New Yorker, August 22, 2020, →.

See also: Samia Henni and Mostafa Minawi, “Reading Colonial Landscapes in Algeria and Palestine,” The Funambulist, December 16, 2019, →; Ariella Aisha Azoulay, “Palestine is There, Where it Has Always Been,” Cornell AAP, accessed September 9, 2024, →; Eyal Weizman, Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation (Verso, 2007); Eyal Weizman, “Walking through walls: Soldiers as architects in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict,” Radical Philosophy 136 no. 8 (2006), →; Mahdi Sabbagh, “Taking Stock of an Unrecognizable Gaza: What Israel’s bombing has wrought,” Curbed, February 8, 2024, →; Mabel O. Wilson, “Concerning the Violence of Architecture” in Their Borders, Our World: Building New Solidarities with Palestine, ed. Mahdi Sabbagh (Haymarket Books, 2024); Rachel Kushner, “Why Did You Throw Stones?” n+1, Summer 2021, →; Owen Hatherly, “Apparatus of Capture - Architecture in Israel-Palestine, 60 Years On,” Archinect, May 27, 2008, →; and Nurhan Abujidi, Urbicide in Palestine: Spaces of oppression and resilience (Routledge, 2014).

“Black-Palestinian Solidarity: 1968 / 2018,” Columbia GSAPP Events, accessed September 9, 2024, →; “Architecture Against Apartheid: A Teach-in on Palestine,” Columbia GSAPP Events, accessed September 9, 2024, →; “Machines,” Columbia GSAPP Events, accessed September 9, 2024, →; “Settlement / Camp,” Columbia GSAPP Events, accessed September 9, 2024, →; “Anooradha Iyer Siddiqi,” Columbia GSAPP Events, accessed September 9, 2024, →; “Stone Men,” Columbia GSAPP Events, accessed September 9, 2024, →.

Architects and Planners Against Apartheid, “Architecture and urban planning organizations stand in solidarity for Palestine” e-flux, May 24, 2021, →.

e-flux, “A Letter Against Apartheid,” e-flux, May 26, 2021, →.

Rachel Hunter Himes, “Museum Pessimism,” n+1, Summer 2022, →.

For two examples of intellectuals grappling with these questions, see: Bruce Robbins, “Student power,” The New Statesman, May 13, 2024, →, and Kaé Sera and E. Tani, False Nationalism, False Internationalism: Class Contradictions in the Armed Struggle (Seeds Beneath the Snow, 1985).

Sami Khatib, “Against singularity: Palestine as symptom and cause,” Radical Philosophy 216, Summer 2024, →.