March 15–17, 2015

In its third iteration under Swiss direction (Art Basel purchased the Art Hong Kong fair in 2013), Art Basel Hong Kong features an abundance of works that wobble, waft, or otherwise cross the threshold between different modes of sensory perception, in attempts to break with an exhibition format and context that otherwise utterly negates the potential for organic encounters and experiences. Within the sterile grounds of the Hong Kong Convention Centre, the works that appeal to the broader sensorium are the ones that manage deliver both aesthetic and conceptual acuity.

Paradoxically, Hong Kong is a sensuous city. Its dewy sub-tropical climate is a contributing factor, but so too is the sheer scale of both the built environment and the social changes that elicit such visceral reaction. This can be unpleasant (vertigo-inducing heights, over-crowding) or sanctifying (air-conditioning, elevated walkways, and perfumed tissues), and the everyday is a constant negotiation of polarizing physical, ideological, and historical elements. In the commercial context, such colonization of airways is palpable, as various enterprises compete for one's attention—shopping malls pump patented aromas, advertisements play musical jingles—thus it is perhaps unsurprising that in the context of the art world one finds accentuated stimulation.

At the fair, several galleries have made a concerted effort to break the mold of repetition and conventional booth settings to allow for more sustained interactions. In the “Discoveries” section, for example, solo and two-artist exhibitions featuring emerging talent flaunt their newness by allowing for a more open exhibition design. At Star Gallery from Beijing, Ling Wen and Yan Cong (the latter a prolific Chinese comic artist) are unveiling new, child-like drawings in lurid hues each day. Nearby, Hong Kong artist Trevor Yeung's solo exhibition at the local Blindspot Gallery envelops the visitor in a small forest of domestic plants. While ostensibly for decoration, the plants are paired with works of art— for example, The Enigma (Sheung Wan) from 2015, in which the artist seeks to play with frames of vision—and are therefore available for purchase. Perhaps the most compelling work in the section is the performance Pastoral Music (2015–ongoing) by Yeung's fellow Hong Kong artist Samson Young, presented at AM Space, Hong Kong, in which he attempts to recreate the soundscapes of war (such fictional compositions have apparently been employed by the US government in order to throw off the enemy) using electronic devices timed to real-life footage of bombs dropping in Baghdad.

A port city and major financial center, Hong Kong has long been known as the bridge that connects the East and West. Investors looking to tap into the Chinese market stake their claims on the territory, encouraged by its liberal trade models. In the art world, international blue-chip galleries have set up satellite locations bringing with them collectors and new audiences. Despite this expanding art scene, however, Hong Kong still has no major contemporary art institution to call its own, though M+ Museum for Visual Culture is slated to open its doors in 2017. In the meantime, an art fair like Art Basel is filling this gap, charged with the responsibility of being not only lucrative but also educational. Accordingly, the fair's program, which places a special emphasis on the region's offerings, extends further to include public talks and seminars (with names like "Post-global: After Identity Politics") that question what it means to be part of the global art world today.

The “Encounters” section places large-scale works at the exhibition space's major axes. In past years, under the curatorial direction of Yuko Hasegawa (also Chief Curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo), these installations breathed life into the monotony of the fair’s grid, by calling for viewer interaction (for instance, last year, Singaporean artist Lee Wen instigated a circular game of ping pong with Ping Pong Go-Round, 1998/2014). This year’s selection, however, curated by Artspace’s Director Alexie Glass-Kantor, seems slightly restrained. At the local Hanart TZ Gallery, a giant landscape ink painting by Xu Longsen (Beholding the Mountain with Awe No.1, 2015) seems to invite an indulgent “artselfie,” while Wang Keping's wooden sculptures, presented by 10 Chancery Lane, also from Hong Kong, are slightly lackluster, standing like two giant fertility totems.

In other parts of the fair, Mika Tajima's series of gradient acrylics (“Furniture Art,” 2014, at Eleven Rivington, New York) appear at once rendered and natural; Charwei Tsai's durational work Water Piercing Stone (2015) melts away a mass of soap through a steady drip of water at TKG+, Taipei; and Ken Okiishi's digital painting gesture/data (feedback) (2015) blinks and wobbles as if to jump the confines of its HD monitor frame at Pilar Corrias, London.

But the fair itself is not contained; it seeps into other sectors of the city voraciously. In Central, just a few train stops away from the convention center, Hong Kong’s Edouard Malingue Gallery is hosting an exhibition by Wang Wei, in which the artist has transposed a panoramic jungle mural extracted from the Beijing zoo (Two Rooms, 2015) onto the gallery walls. Wang, who is considered a proponent of China's Post-Sense Sensibility movement of the late 1990s and early 2000s, invites visitors to consider the artificial environments that structure the display of both contemporary art and wildlife in captivity. On the 13th floor of a nearby office building, a group exhibition titled “The Tell-Tale Heart,” a joint effort between Shanghai's Leo Xu Projects, Pilar Corrias Gallery, and the local K11 Art Foundation, brings together work circling around themes of narration and perception. Ian Cheng's live video simulation (Something Thinking of You, 2015) suggests that consciousness is learned and not inherent, while Cheng Ran's LP record HIT-OR-MISS-IST (2013) blends soundscapes recorded by the artist on the island of Réunion, in Amsterdam, and in Paris, alluding to growth and expansion.

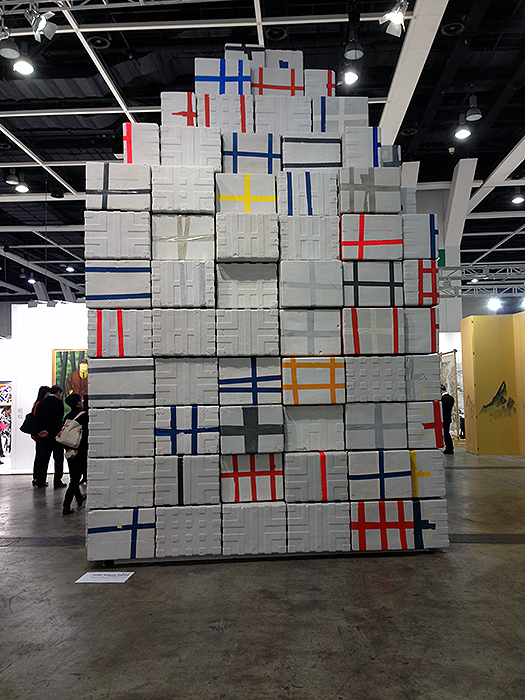

Returning to the fair grounds, walking past Yang Maoyuan's inflated taxidermic experiments ("THEY" are coming to Hong Kong, 2014, at Platform China, Hong Kong) and João Vasco Paiva's monumental tower of Styrofoam boxes rendered on stone resin modules (Mausoleum, 2015, presented by Edouard Malingue Gallery), a video work (Radio Piece, 2015) by David Claerbout for New York’s Sean Kelly quietly speaks to the reality of global cities where physical space is increasingly scarce. "In Hong Kong," the “Encounters” section’s curatorial text posits, "mental space has already become the new real estate." Can art provide a sanctuary for the senses or does the context of an art fair lend itself instead to their total domination?