May 15–18, 2014

At an art fair like Art Basel Hong Kong—now in its second year—what it means to be “truly global” warrants some reflection. For the fair’s global director Marc Spiegler, it meant increased participation from western galleries, artists, and collectors, creating a more “global” market for Asian art and a seemingly more “global” art for Asia. The European and American-centric nature of Spiegler’s definition aside, this shift did allow for a greater diversity of presentations, many coming from younger galleries keen to respond to the context of the fair itself. Overall, the participating artists appeared conscious of such problematic qualifications of the global, leading to works and showcases that emphasized the latter’s increasingly oblique and virtual character.

This scenario was reflected in several works in the curated Encounters section of large-scale sculpture and installation works—notably Yu Cheng-Ta’s The Letters (Live Performance) (2014), presented by Chi-Wen Gallery from Taipei. Comprising a green-screen set, in which actors periodically read aloud spam emails about advance-fee fraud schemes, The Letters raises the question of exactly what encounters in the digital realm entail, as well as the ease with which identities can be concealed within it. That exchanges of capital often drive such confrontations is also significant for Sun Xun’s Jing Bang: A Country Based on Whale (2014), a project co-presented by the Singapore Tyler Print Institute (STPI) and ShanghART (Shanghai/Beijing/Singapore), which invites people to obtain a temporary visa or full-fledged citizenship (selling for 30 and 10,000 dollars, respectively) to the artist’s fictional state of “Jing Bang.” While visa holders received a digital print, citizens were given a Jing Bang toolkit that includes a hand-bound passport and cultural guide. I found the latter’s allegorical embrace of communist-capitalist politics in China especially refreshing, given that all political beliefs—whether communist or capitalist—incorporate varying degrees of contradiction and deception.

The participatory nature of these works reflected returning curator Yuko Hasegawa’s more literal interpretation of the section’s title, which itself connects to a wider trend within art institutions, biennials, and fairs of placing visitors at the center of “the art experience.” Whether a parody of this trend, or simply an attempt to inject some humor into the fair, Lee Wen’s Ping Pong Go-Round (1998) from Singapore’s iPRECIATION was a hit with exhibitors and visitors alike, mainly because of the sheer novelty of playing pint-sized table tennis amidst artworks with million-dollar price tags. Other works in the section felt more like set pieces than participatory platforms, such as ESLITE GALLERY’s presentation of Michael Lin’s Point (2014) and Cecilia de Torres, Ltd.’s commissioning of Marta Chilindron’s Cube 48 Orange (2014). Besides serving as welcome places to loiter, these works offered little in terms of addressing the complicated contexts and conflicts that define human encounters. The fair’s biggest disappointment was Tobias Rehberger’s Homeaway (2014), another re-creation of the Frankfurt art watering hole Bar Oppenheimer, featured by Beijing/Lucerne’s Galerie Urs Meile and Berlin’s neugerriemschneider; its guise as an art project did little to conceal its tame aesthetic (previous iterations of the bar have been dizzyingly psychedelic in form) and clear pretense, with a note on the counter informing visitors that Homeaway was “not a fully functioning bar.” Visitors seeking more epic levels of interaction should look out for Carsten Nicolai’s α (alpha) pulse (2014), a new, Art Basel-commissioned light pattern and soundtrack (available through an app designed by the artist) that will be projected onto the façade of Hong Kong’s International Commerce Centre (ICC) starting this evening.

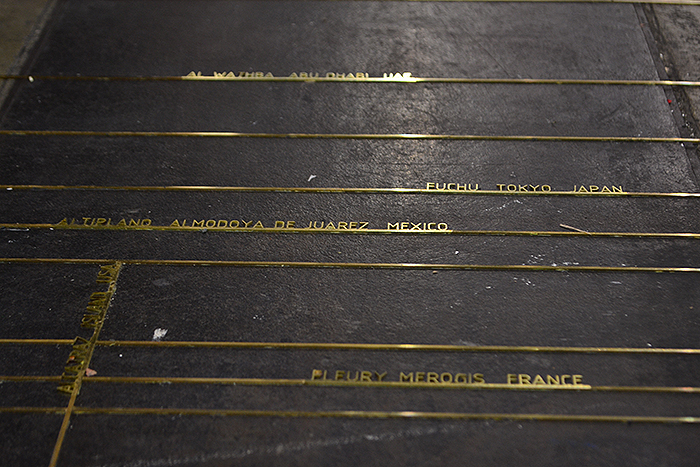

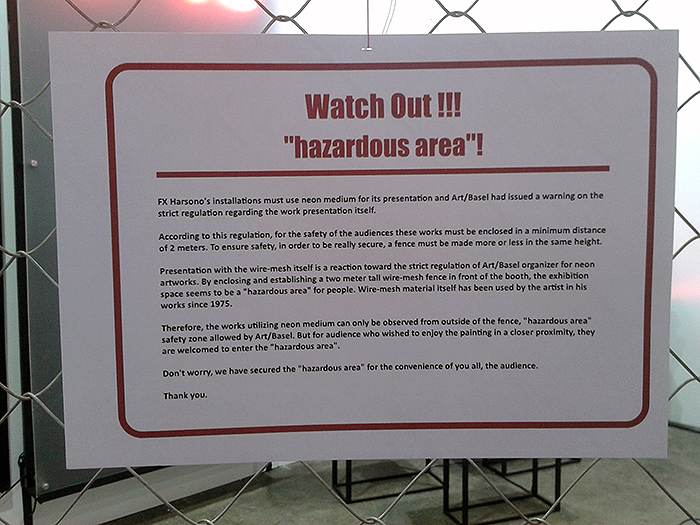

These staged set-ups were paralleled in Insights, a section of the fair devoted exclusively to presentations of Asian artists by galleries in the region. Galerie Paris-Beijing’s selection of Yang Yongliang’s collages of urban landscapes resembling Chinese ink paintings, for instance, was rather predictable, as were works by Wang Yabin and Guo Gong at the booth of Beijing’s NUOART that referenced various tropes and materials of the Chinese ink medium. More inspiring works, like Filipino José Santos III’s fabric assemblages at Artinformal from Mandaluyong City, and Ahmed Mater’s photographs at Saudi Arabia’s Athr Gallery from Jeddah, went beyond their booths’ limited scope, showcasing careful selections from ongoing bodies of work that themselves acknowledge the challenges of singular representations (of everyday objects and the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, respectively). At Jakarta’s Galeri Canna, Indonesian artist FX Harsono was forced to take the limited parameters of the booth into his own hands, erecting a wire fence around his installation that measured and stipulated the minimum distance required between neon works and the public.

Given the restricted space offered to galleries in the Discoveries section of the fair, similar limitations of space functioned more as sources of creative inspiration. Tunis-born, Berlin-based Nadia Kaabi-Linke’s overlapping of the booth assigned to Kolkata’s Experimenter with measurements from standard-sized prison cells was both poignant and ironic in its equation of artistic display with solitary confinement; the work, In confinement my desolate mind desires (2014), has earned the artist this year’s prestigious Discoveries prize. Other booths deliberately gave the appearance of being in the midst of installation, such as Bettina Buck’s exhibition of Plinth Drawings (2014) at London’s Rokeby, which included cardboard replicas of the pedestals used for Auguste Rodin’s sculptures at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London; they served as points of references for various works that looked at ideas of packing and unpacking. Further circular aesthetics and narratives can be caught in the fair’s film program, curated by founder of Beijing Art Lab Li Zhenhua, which includes selections of early video works by Swiss artist Roman Signer and screenings of Vietnamese artist Dinh Q. Lê’s South China Sea Pishkun (2009).

The most courageous and understated position—not only in Discoveries but in the fair overall—came from German artist Daniel Gustav Cramer at Zürich’s BolteLang. His Works (Three Days) (1930/2014) incorporates a small black-and-white photograph of the Matterhorn mountain on the Swiss-Italian border that the artist’s grandfather took 80 years ago, alongside recent views of the peak. Cramer’s sparse arrangement of the photographs left ample space for viewers to wonder about the unbridgeable distance between such polarities as past and present, as well as life and death. Further bold offerings appeared in the general section of the fair, with Melbourne’s Anna Schwartz Gallery presenting punky juxtapositions by Australian artist Shaun Gladwell and Singapore-based Heman Chong, and Guangzhou’s Vitamin Creative Space featuring an intimate selection of works by its represented artists. Among the latter, I especially warmed to Pak Sheung Chuen’s White Library/A Mind Reaching for Emptiness (2009), a work that consists of printed scans from various cover pages of books consulted by the artist during a recent residency at the Asia Art Archive in Hong Kong.

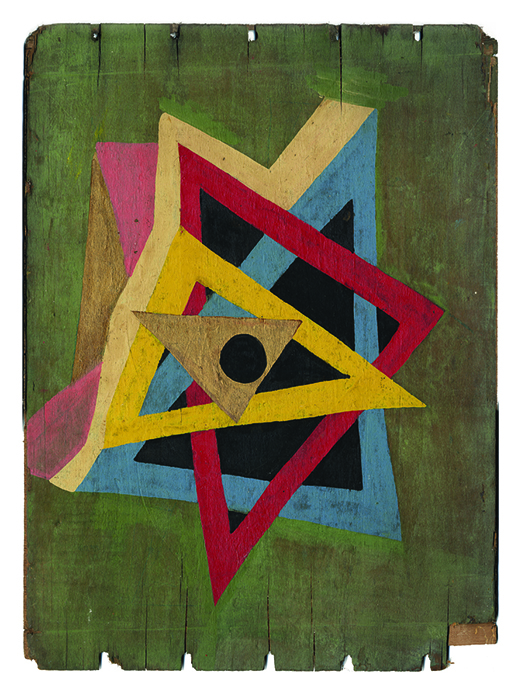

Perhaps the work’s nirvanic state of emptiness appealed to me after a day packed with artistic consumption. At the end of it all, and despite several worthy displays, I am still surprised at how little of Art Basel Hong Kong’s 2014 edition remains in my thoughts. Reminding myself of the impossibility of meaningful viewing in this context, I feel less guilty, and able to contemplate the works I do recall, among them a series of paintings by Antiguan artist Frank Walter (1926–2009) presented by Ingleby Gallery, Edinburgh. Using whatever materials he could find—from cardboard boxes to scraps of driftwood—Walter painted in a way that was both humble and direct, his simple abstractions of the Caribbean landscape, like the undated Tree With Red Leaves and Rainbow Cruise Ship, belying their mastery of figure and form. These paintings, and their roots in a specific time and place, remind us that aspirations towards the truly global can only ever be utopian, and how those very claims towards transcendence rely on continued assertions of “the local.” It is discoveries like these, moreover, that could give new sense to what it means for an art fair to be “truly global”—that is to enable undervalued artists in overlooked locations to earn deserved recognition, whether at home or abroad.