March 22–May 3, 2014

Eighteen years have passed since Hal Foster’s critical remarks on the position of the artist as ethnographer.1 That text, together with Catherine David’s 1997 Documenta X, and its questioning of the anthropological foundations of Western culture, became two groundbreaking events, which heralded a tightening of the artistic and anthropological inquiries that have emerged up to the present day.

If the early 2000s witnessed a period of relative downturn in interest for the methods, topics, and scenarios of ethnographic observations and anthropological comparative analysis, we are currently experiencing another ethnographic revival in artistic practices, which—just as in the mid-to-late 1990s—has been simultaneously evidenced and stimulated in exhibitions by both theoretical ventures like Anselm Franke’s “Animism” (2010–12), and major perennial platforms like Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s Documenta 13 in 2012.

Marine Hugonnier is a London-based artist who has been carrying out a long-standing exploration of the crossroads between anthropology and philosophy. “The Bee, the Parrot, the Jaguar,” her solo show at Galeria Fortes Vilaça, presents an important moment in her inquiry, which engages with the writings of Brazilian anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, a key figure for current trajectories in philosophical realism and the critical evaluation of modernity’s culture/nature dualisms.

All sorts of potential life forms created by Hugonnier inhabit the exhibition: objects, images, and situations for which the lines between symbolism, representation, and embodiment have been intentionally blurred by the artist. Occupying the large subterranean room of the gallery, the space becomes a sort of enclosure for the presence of these multiple beings. The first encounter takes place at the entrance, where an isolated red figure, Anima(L) (2014), which vaguely resembles a hollow pyramid or a stylized mountain peak, faces the visitor. It is the largest of a series of four groups of relatively small aluminum-coated steel sculptures all titled Anima (2014), which are arranged according to their color (red, green, yellow, and blue) and formal properties. Some are presented alongside other elements, as is the case of the red Anima, which is accompanied by a large stock photograph of a black panther.

Each Anima group is displayed on a different sized support, of which the top surface is made of mirrored glass that absorbs and projects the surrounding environment, incorporating the visitor into its inverted image. Besides the appellative call of the reflecting surfaces, there is something deeply enthralling about these sets of abstract geometric figures, which are sort of tropical, ludic, decorative adaptations of Russian Constructivist forms. Their size and ease of accessibility invite the visitor to handle and move them around in a hypnotic interplay between holding, playing, seeing, and being seen.

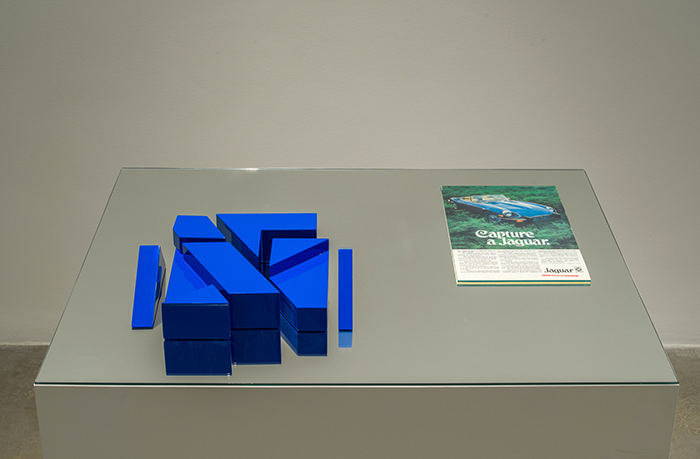

Towards the left, the green Anima—on the lowest pedestal, at coffee table height—appear like a funny-looking group of perfectly round, bright green spheres; assembled around a series of oval tropical fruits (avocados, limes, kumquats, guavas, and papayas), the set becomes a unified ensemble where there are very little distinctions between the fruits and the metal orbs. The set is paired with a found sculpture of a Were Jaguar (2014), an Olmec transformation figure thought to depict the metamorphosis of a shaman into the animal, which the artist enhanced with gold leaf. Nearby, the yellow Anima consist of four irregular shapes that recall the blocks of an infant’s hole-fitting toy, and perched in the upper-most left corner of the room, on the tallest of the four plinths, the blue Anima, an array of International-Klein-Blue, flat solids—mostly rhomboids and triangles—are flanked by a 1970s magazine advertisement for a Jaguar E-Type, associating the car’s brand name with a wild beast, and drawing a connection between hunting, consumerism, and colonialism via its slogan, which invites the viewer to “Capture a Jaguar.”

Atop the fifth pedestal is a book entitled Forest (2014). It consists of a large assemblage of magazine clippings with jungle scenes that are cut lengthwise in three sections permitting the various pictures to mix with previous and subsequent ones, and to form multiple combinations of images: animals evolve into plants, skies give way to leaves, and treetops become leopard fur in a beautiful interchange of ways of being.

Various forms of contact and the possible interactions between things are also at the heart of the main work of the show, the 26-minute, 16mm film Apicula Enigma [The Enigma of the Bee] (2013). Shot in the French Alps, it introduces a spatial derivation from the exhibition’s preponderant Latin-American geographic references, while at the same time offering a bucolic, slowed-down documentation of a film crew in its attempt to establish contact with a human-made hive of honeybees. What the film depicts—more than the animals, the film crew, the landscape, or the beehive—is the insuperable separation between humans and animals, the concrete distance of which is measured throughout its various takes without any attempt to anthropomorphize the insects, whose deafening, outlandish buzz echoes all throughout the gallery.

It seems curious that distance—as well as resistance (to time, to translation, and to interpretation)—remains a fundamental issue for the debate around the critique of the naturalization of the chasm between nature and culture. Distance was the key topic of Foster’s 1996 text, which questioned the artist’s true capacity for reaching the quested Other, whose presence was positioned far beyond any possible contact. Distance is also at the core of Viveiros de Castro’s studies on the Amerindian “animic-perspectival ontologies,” in which he argues that the main difference between human and non-human animals lies with their distanced point of view: what humanity sees as nature is seen by other species as culture (he also famously stated, “what man sees as blood is seen by the jaguar as manioc beer”).2 The insurmountable distance between things, people, animals, and places is also at the heart of this ambitious exhibition, which presents a very delicate balance between theoretical concerns, abstract reifications, and research on popular sources of imaginary.

Hal Foster, “The Artist as Ethnographer?,” in The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century. (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1996), 302–309.

Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, “Exchanging Perspectives: The Transformation of Objects into Subjects in Amerindian Ontologies,” Common Knowledge, vol. 10, No. 3 (Fall 2004), 463–484.