October 12–November 27, 2010

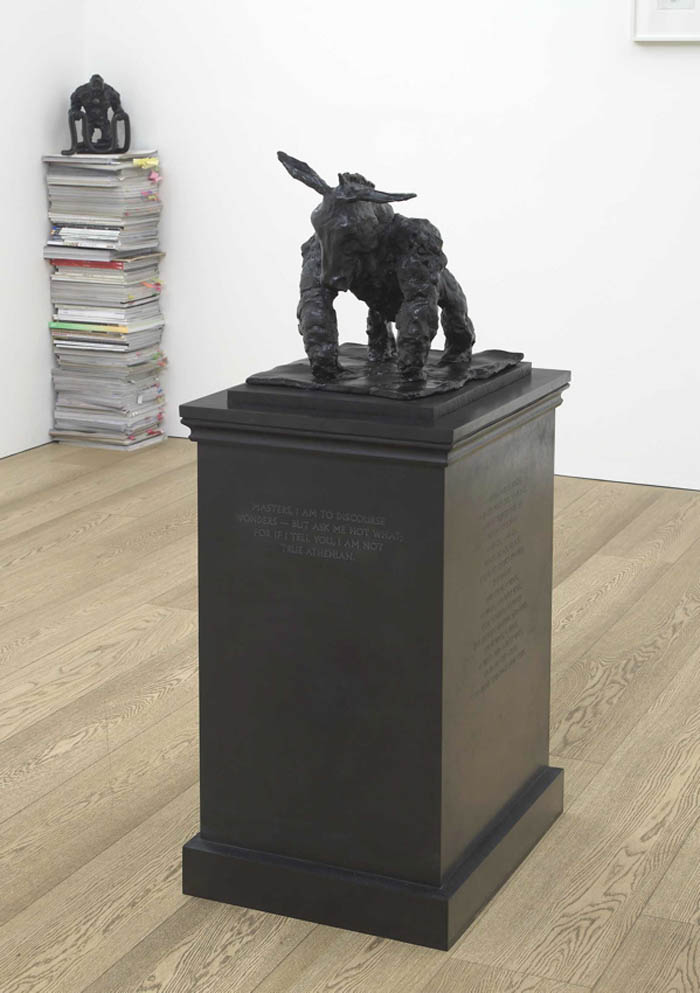

Beyond the overwhelming personal tragedy, one of the many unfortunate consequences of suicide is that a life's work is often mitigated through the lens of it. For Angus Fairhurst's first gallery exhibition since his 2008 suicide, it is at once impossible to elide this tragedy yet simultaneously a disservice to let the artist's death supersede his work's autonomy. Curated and installed by artists Rebecca Warren and Urs Fischer at Sadie Coles HQ in London, the exhibition seeks to join key works in Fairhurst's career, ranging from intimate graphite drawings to various sculptures to a larger installation downstairs. Most compellingly on display are Fairhurst's iconic bronze gorillas supported by newly constructed plinths in tribute to the artist. Commissioned by Warren and Fischer, the plinths range from a hefty, inscribed cast iron totem (designed by Damien Hirst) to castoff cardboard banana boxes, all created by sundry fellow Young British Artists.

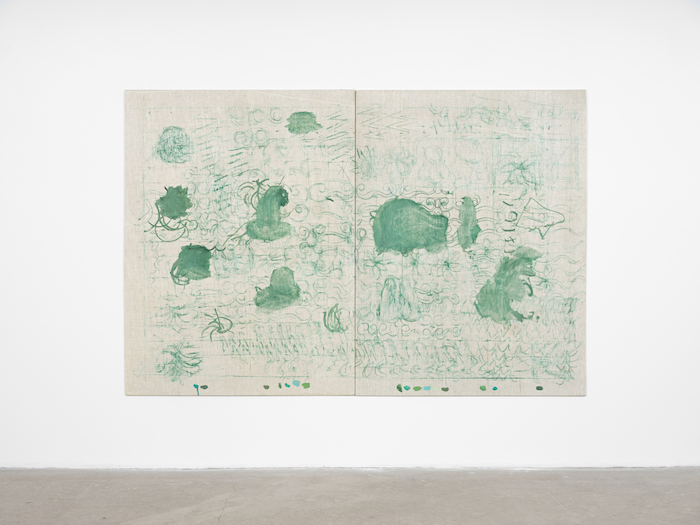

Fairhurst, a lesser-known contemporary of YBAs Sarah Lucas, Tracey Emin, and Gary Hume, rose to prominence in the early 1990s exhibiting throughout England and Europe. His infamous 1991 prank commenting on the insularity of the art world, "Gallery Connections," put confused attendants of London art museums and galleries unwittingly in touch with one another on the phone, which resulted in a hilarious transcription (soon after used in the pilot issue of frieze). [i] Fairhurst's work is neither morbidly brooding nor explicitly comical, but exists as a poignant amalgamation of these two poles, often embracing a one-off jamming of communication and censorship. As evidenced by this posthumous exhibition, the artist employs the aesthetic sensibility of cartoons and comics, toying as ever with humor and playfulness. Yet in his studies and sculptures, gorillas (Fairhurst's metaphor for the human consciousness, or man's "animal nature") interact obtusely with objects ranging from bananas to fish, without the feed-line-then-punch-line vernacular usually associated with jokes or comics. A Couple of Differences between Thinking and Feeling (Flattened), 2002, takes a bronze gorilla and seemingly runs a steamroller over all of the animal, albeit sparing its head, which makes it curiously akin to a pathetic gorilla-skin rug. Titles of his drawings and bronze works point to varied philosophical and cultural references engaging the complex interstices of the human consciousness, will, and existential futility. An obvious reference to Søren Kierkegaard's tome on the internal struggle for personal freedom, A Couple of Similarities to Either/Or, 2006, finds a bronze gorilla holding a limp tube atop a stack of indexed art magazines—the plinth of which was designed here by Juergen Teller. Another bronze piece, Lessons in Darkness, 2008, appears to be at once a dead coral or creepy tumbleweed, its title taken from German director Werner Herzog's 1992 film taking place in the barren, post-Gulf War Kuwaiti landscape. The Birth of Consistency, 2004, finds a gorilla gazing into an oval mirror, referencing the myth of "Echo and Narcissus." The gallery basement houses Fairhurst's melted bus shelter and bench (created out of bioresin), an abstracted structure bearing no advertisements or text, furthering the artist's engagement with self-effacement and aestheticized censorship.

Perhaps strange here is the staging of the artist's first posthumous solo exhibition in a commercial setting aided by all sorts of his institutionally successful friends, their function stated by the curators as "enlivening the sculptures' posthumous display." No doubt, the plinths commissioned by Warren and Fischer provide a new and at times compelling take on Fairhurst's work. But, for all of the artist's gifts in sensitively illustrating the ineffable intricacies of human life, Fairhurst's work, powerful and vital as ever, needs no additional support.