McKenzie Wark

There are more than a dozen books both by and about trans women coming out this winter and spring. As someone who’s been reading trans lit for a while, there’s something surreal about that to me. As if someone had been secretly putting estrogen in the break-room coffee at all the publishing houses.

Some of these books are from major publishers and are conventional in genre and style. Some are from independent presses and have more willful forms. Those appeal more to my own tastes, but as a trans reader and writer, what really makes me happy is the variety. I just love seeing transsexuality expressing itself across a range of literary forms and positions in the marketplace of books.

One of my favorites is Vivian Blaxell’s Worthy of the Event (Little Puss Press). It presents itself as an essay, and like any good essay, it has a lovely branching and diverging form—as does the life it documents. Coming out as a transsexual will usually send your life sideways, in ways both predictable and not. This is a book about how to be worthy of what happens to us, how not to be disappointed with life, to embrace wanting what we want. Blaxell:

Girls like me are often good at disappointment. Girls like me learn not not to be disappointed; we learn how to be worthy of it. We learn to dilute disappointment and wash it down the drain; how to scrape the disappointment off without abrasion several times a day or how to walk past disappointment looking fabulous or how to turn disappointment into a bit worthy of us.

My favorite part of the book is about being and becoming, although it’s a difficult read for me, because it’s partly about me, or rather it’s Blaxell’s reading of how I presented my own transition via social media: “Does McKenzie Wark have some stop up ahead there at which she gets off becoming herself and enters a state of being, or is her becoming, and all becoming, the true condition of life?”

The answer to that turns on what we take to be in flux, and what a fixed property. “Like a lot of us, McKenzie Wark is both an unchanging abstraction and a constant unlocking of herself to become something and somehow else.” What’s the unchanging abstraction part? The fixed property, it turns out, is property:

McKenzie Wark has not lost her professional networks, not her job, not the space in discourse she made for herself before becoming a woman. Just the opposite. McKenzie Wark has used her becoming woman to expand the reach of her voice, to refresh her writing and create new opportunities for herself.

Can’t say that doesn’t hurt, but it’s not untrue.

Blaxell’s writing works through divergence, Jamie Hood’s through repetition. Trauma Plot (Pantheon) is a book about what happens when you can’t let go of the sense of worthlessness of your own life. It’s also a defense, without being defensive, of life writing and of writing through trauma. Perhaps we could undo the hierarchy which proposes that “imaginative” writing, aloof from life, is somehow more valuable than what’s written in the thick of it.

Perhaps we could also undo the common prejudice that writing from experience is somehow a more market-made artifact. Writers with boring lives, who stake their value claim on “imagination,” are just a bit too anxious about what they (we) actually are—boringly secure and middle-class types. More settled-down being than rave-up becoming. Maybe we could make some space in the category of the “literary” for writing which is worthy of the event, of what happens, which lets in a lot of writerly lives, including those of many trans women. Shit happens to trans women. Hood: “I write for the messy bitches. I write for girls who haven’t given their grief language.” She not only gives such lives language, but does it artfully, and well.

There’s a popular game, which I’ll call “neoliberal criticism,” which identifies a style of writing, locates a few random examples of it, claims these are the trend, and then points to them as emblematic of perfidious neoliberalism—thereby magically exempting the rest of the literary market from sin. I call it “neoliberal criticism” because all it does is point to a bad product to add value to a good product.

What might be more interesting is working from the premise that the whole of “literature” is internal to capitalism, and finding a plurality of ways to write about that from within. That’s what these trans books do. The deck is stacked against trans writers, who are less likely to have access to the MFA-to-agent-to-book-deal pipeline. In literature as in life, we learn to be cunning.

From its knowing title on in, Trauma Plot is a sophisticated kind of life writing, and does something far more interesting than claim authenticity through the immediacy of experience. Hood:

Of course the spark of writing, like desire, is often opaque to us, has its own beingness, or (lacking a better term) its own soul, and if you’re a real writer (can I use that term?), you understand that writing must carry you elsewhere, outside yourself, your ego, well beyond the boundaries of your control … There’s a mystery there, an enigmatical quality, and the person recording that soul is indispensable to its transposition but also, necessarily, exceeded by it.

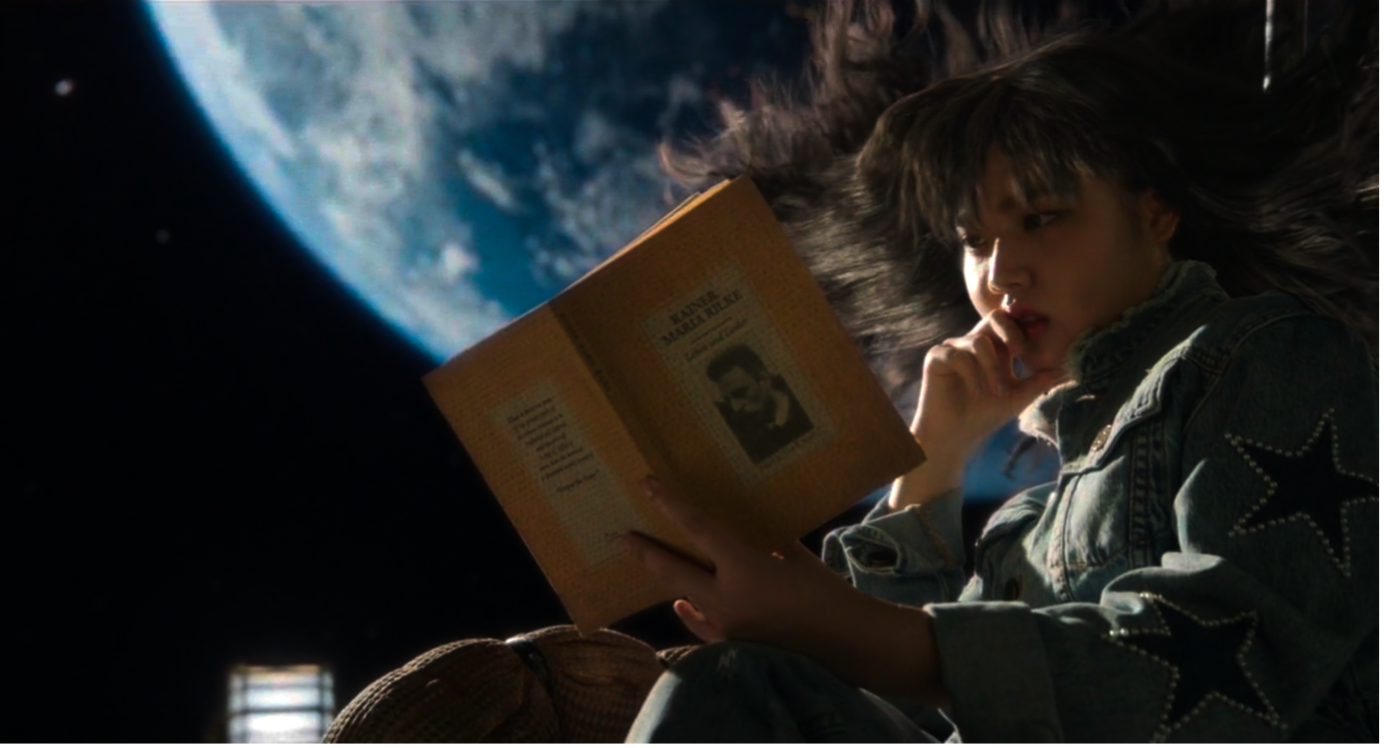

Trans books, to trans readers, are more than objects of disinterested contemplation, although that does not negate the possibility that they can also be objects of aesthetic appreciation. For a lot of trans women, the aesthetic is a life-or-death matter, and in more ways than one. Books, preferably not just about us but by us, are one of the few places we can learn how to appear, how to become, how to be.

There’s a directness to Hood’s sentences. They cut to the matter. Aurora Mattia does something very different in Unsex Me Here (Nightboat). Her sentences are crammed with clauses, her clauses with glittering, gleaming objects, her objects adorned with modifiers, her modifiers with yet more modifiers: “No one told me I could wear lipstick and so I was silent, because they did not give me words to use, I had to make them up. That’s why I write such crude and unbalanced phrases. I had to make them up myself. There was no story for a boy in lipstick.” Trans lives, trans writing, transgress the generic form of bodies and sentences.

The elaboration of the sentence in Mattia might also be a form of intentional misdirection. Mattia: “Transparency means explaining myself, which means, in turn, paying attention to, and responding to the ways my selfhood is predetermined by the algorithm of the state.” As I write, we’re at the tail end of the era of “transgender representation,” the myth that visibility would lead to sympathy would lead to our embrace within the compact of the liberal public sphere.

Mattia: “In a more so-called ‘liberal’ interlude of american empire, the State decided to absorb the concept of trans people. This process of absorption, what we call ‘representation,’ is how the state attempts to make surveillance attractive to me.” Blaxell, Hood, and Mattia find very different ways of being seen and not seen on the page. They work in and against the cis gaze, which always wants to put us in our place, as the bad object, the one whose exclusion stabilizes the genders for everyone else.

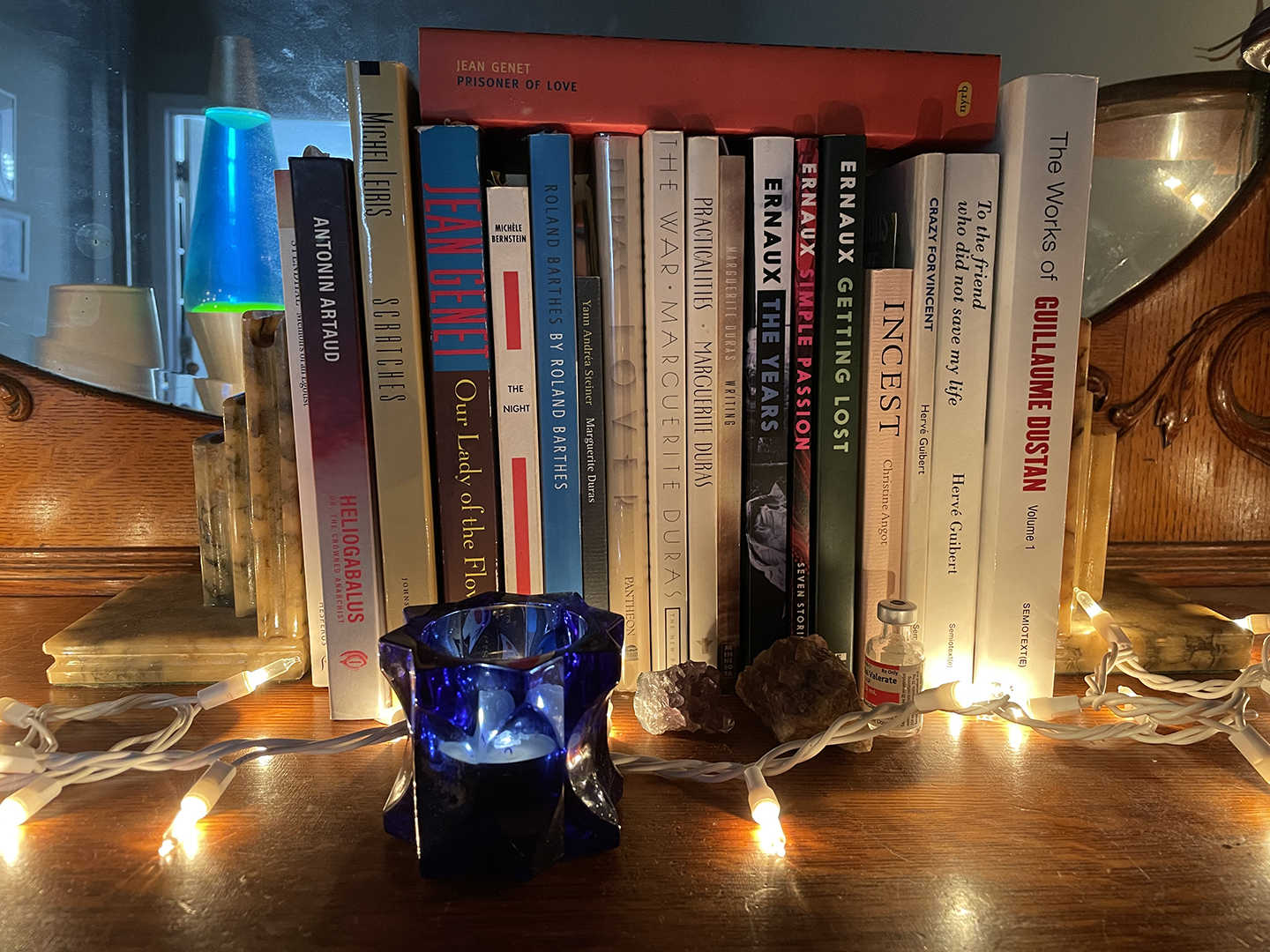

Trans writers might once have felt like we were writing in a vacuum, scratching about for ancestors. If there’s something distinctive about this moment for trans writers it is the thickening of our culture, the expansion of the archive from which we can draw. My favorite part of Harron Walker’s essay collection Aggregated Discontents (Penguin) is a long chapter on Greer Lankton, a New York–based artist who, had she lived, would be my age now.

Walker offers the richest, most nuanced account I’ve read of Lankton’s life and work. She is careful not to reduce the work to the life, or to discount it either. Lankton’s best-known art takes the form of dolls. Those dolls are sometimes trans women. Those dolls of trans women have dicks. Why did Lankton sculpt dick girls? It’s not a question that comes up much. Nobody ever seems to object, as a liberal-minded observer might if a cis artist made them. Walker: “No one thinks to question why a trans woman would sculpt so many women with penises … We don’t accuse her of fetishizing her transsexual subjects’ bodies, in part because of our own projections onto the bodies of trans women—yes, even Lankton’s.”

The body with tits and a dick is the very image of trans-femininity to the cis gaze. And yet here it is in the art of Lankton, a trans woman—who had bottom surgery. How are we to think about that? She gets a pass for reproducing a common cis image of us, because she was trans but not herself a dickgirl. Should only girls with dicks get to picture girls with dicks? That seems absurd. Nobody is outside the structure of the cis gaze, which is driven by anxiety about ambiguously sexed bodies, resulting in the dual impulse to fetishize and punish such bodies. Not even Lankton, or Walker, or me escape it.

Walker pores through Lankton’s archives of photo-booth selfies. Formally, they’re not so different from the pictures I posted on social media, the ones that caught Blaxell’s eye. Walker: “Have any of us ever done anything new? She’s even using the third person to caption her own photos. How beautifully unoriginal we are.” I love that for us. This constant play of image and flesh, being and becoming. The static being of the image a guide to the organic becoming of the body.

It’s helpful to have a trans culture upon which to draw, but many of us had to figure ourselves out with whatever culture was at hand. That’s the premise of The Dad Rock That Made Me a Woman by Niko Stratis (University of Texas Press). It’s great that there are so many trans books coming out, but to nobody’s surprise its trans women who came from money and/or had a formal education who mostly get to write them. Transition can kick a transsexual out of the nest in the tree of class privileges, but it still helps to have been there before plunging earthward. Like her father, Stratis worked in glass factories and other manual trades, and found the thread of a life through music.

Music remembers for us. Stratis: “I don’t always have a great memory; sometimes it takes great skill and concentration to remember anything that happened to me in the years before this one. Music always brings me back to this place. I forgot a lot of my past, but that’s not to say that it is gone.” I’m not particularly fond of “dad rock,” but Stratis shows us how so many of these songs, mostly by men, have an emotional openness and expansiveness that’s not so common in pop music anymore. They form the thread through the book, as Stratis bumbles through family, relationships, jobs, not quite being who she needs to be.

Who knows how much good trans writing came and went through the rise and fall of Blogger, Live Journal, Tumblr, and other social media platforms. Or how much trans literary genius is expended on dating sites. In How To Fuck Like a Girl (Dopamine and Semiotext(e)), Vera Blossom writes: “These Craigslist encounters were exercises in creative writing. I’d write roles and cast myself and some stranger in them.”

The book has the texture of posting. The posts add up to a memoir of a young Filipina trans woman born in San Francisco, raised in Las Vegas, lately of Chicago—who likes to fuck. Sex was once a taboo topic for trans writers. Us being horny gives cis people weird feels. The occasional form of the pieces seems to me to suit contemporary trans life, with its refrains of being broke, changing roommates, jobs, cities. It’s all very direct and engaging and frankly a bit of a break from the style of New York trans writers (myself included) which can get a bit arch.

I expected to feel more affinity with Jennifer Finney Boylan’s Cleavage: Men, Women and the Space Between Us (Macmillan). We’re both white trans women of a certain age who work in academia, although unlike Boylan I was never on the Oprah Winfrey Show, never a columnist for the New York Times, or president of PEN America. Nor do I aspire to any of those things. I suppose it’s no bad thing that there’s a trans writer who is popular, mainstream, and writes and appears within the frame of bourgeois liberal respectability. Yes, Karen, we can be normal! Or almost—we’re always suspect even among the most liberal minded.

The pieces that resonated with me most, as a trans parent, are the ones in which Boylan touches on parenting. In one, she confronts her feelings about one of her own children coming out as trans. Boylan: “I was trying to use my sons as evidence that I was not a bad person.” As if raising “normal” kids would excuse her own transness. It’s a relatable feeling, and also not. I’ve also felt this pressure of the cis gaze on my parenting. I want to resist it, but I don’t want to put my own kids in the middle of it.

Boylan wants the rest of her life to come off as a regular upper-middle-class existence, expressed with humor and grace, albeit one that’s massively overexposed in the media. Which produces the double bind for a nonfiction writer of presenting a small target to the beady eyes of a large public while revealing some of the intimate details of a regular life. No matter how respectable an image trans women have portrayed, we have never escaped the cis gaze, which at best has made us tokens of liberal tolerance and which now shows its ugly side in the campaign to exterminate us.

Maybe we’d be better off taking Joyce to heart and practice “silence, exile, and cunning.” Taking our distance from institutions which make cis gender, heterosexuality, romantic love, and monogamy norms from which a little bit of deviation might be tolerated—but not much.

If there’s a mainstream trans personal essayist who seems more contemporary to me, its Andrea Long Chu. When her essay “On Liking Women” came out in n+1, it was a celebrated piece. It did all the things a good personal essay should. It turned the details of everyday life into the means to craft both a feeling and an idea, in this case about transsexuality. I can just imagine the agents who buzz around journals like n+1 looking for a meal ticket, licking their collective lips.

It turned out that what Chu is really good at is not the essay, it’s criticism. She wants to be Susan Sontag, not Joan Didion. And she is. Or could be. Reading her pieces collected together as Authority (Macmillan), there’s a refreshing pressure that’s sustained in her critical writing that keeps each piece pumped right to the end. It’s exhilarating across a few thousand words but exhausting to read more than a few at a time. Better to sip than chug it.

She’s mostly assigned high-profile “literary fiction,” a marketing category under which commercial publishers ship all sorts of product, good bad and indifferent. It’s hardly the high modernism upon which Sontag sharpened her appreciation. Chu has high standards, and expects literary fiction to be both formally accomplished and intellectually coherent. Publishers sometimes treat the second of those qualities as optional.

The pieces I like most combine criticism and personal essay in the manner of “On Liking Women.” Pieces about disappointment and desire. Chu: “It must be understood how unpopular it is on the left today to countenance the notion that transition expresses not the truth of an identity but the force of a desire. This would require understanding transness as a matter not of who one is, but of what one wants.” Becoming, not being, and being worthy of the event.

It’s a good thing that Chu gets to write about books by and for people who imagine they have regular sexualities and genders, although sometimes I’d like to see her pneumatic prose hose down some trans books to see what’s going on there. What would she make of Jeanne Thornton’s A/S/L (Soho House)? It’s an ambitious book, and I think she pulls it off.

In A/S/L, three teens meet in the world of homemade computer games. They have big plans, which don’t pan out, and they go their separate ways. Many years later their lives intersect again, when the least stable of them turns up in the lives of the other two. Thornton is very good on damaged transsexual lives, on the rolling disaster set in motion, not by transition, but by the way we’re punished for it.

The central characters are all regular working-class people. It’s striking to me how rare that is. The publishing industry sometimes seems laser focused on selling books to affluent, educated white women—about affluent, educated white women like me. A/S/L lets onto the page the everyday struggles around work, housing, social life, and mental health beyond that.

Denne Michele Norris’s When the Harvest Comes (Random House) is about race, sex, and grief. Mostly grief. Davis, the central character, left home after his father found him getting fucked by a white boy. He falls in love, and intends to marry, Everett. It seems like Everett’s close, rich, white family is liberal minded about the whole thing. Until Everett’s little brother says the quiet part out loud: they can accept this gay interracial marriage because they assume—correctly as it happens—that Everett fucks Davis, not the other way around.

The death of Davis’s father, the Reverend Doctor, sends him spiraling. They may be estranged, but the Reverend Doctor is the one who set Davis on his path, as a topflight classical viola player. The book is an elegant account of the complicated grief we can feel for family with whom we’ve had to break—an experience all too common for transsexuals.

That Davis plays the viola is connected to an incipient transsexuality that Davis isn’t quite ready to let out. Unlike a violin or cello, the body of a viola is too small for its acoustic range, leading Davis to remark: “I’m saying I identify with that aspect of the viola—the built-in flaw, the very real limitations to the body in which I navigate the world every day.” And yet he—soon to be she—makes beautiful music with it.

Benedict Nguyen’s Hot Girls With Balls (Catapult) is about a different kind of virtuoso. Its two main characters, Six and Green, are Asian American trans women who play professional volleyball—men’s volleyball. In the parallel universe of the book, it’s become a popular televised sport, with sponsors and a media circus.

It’s a book about twenty-first-century fame and its management. Six and Green are in a clout-gap relationship. The slightly less popular Green can’t help being fixated on their follower counts. Over the course of the book Nguyen reveals many facets to the problem of being both trans in public and also Asian in public, and how the cis gaze and the white gaze interact. The tone is light comedy, but the substance is real enough.

Six and Green have found a way to thrive in the hyper-media era, but this cuts them off from trans community and experience. Class difference is one of the least explored dimensions of trans life. Fortunately, Nguyen doesn’t offer an imaginary resolution to the real contradictions of class. It’s enough to illuminate them.

The existence of Anglophone transgender fiction as something mainstream publishers will even contemplate owes more than a little to two things. The first is the deep work of developing trans writers that happened around Topside Press, a now defunct independent trans publisher that put out some important books, starting with an anthology, The Collection (2012), then Imogen Binnie’s novel Nevada (2013), Sybil Lamb’s I’ve Got a Time Bomb (2014), Casey Plett’s stories A Safe Girl to Love (2014), and Glamourpuss (2016), a collection of poems by Cat Fitzpatrick. Plett and Fitzpatrick later founded the trans-run feminist press Little Puss, publisher of Blaxell’s Worthy of the Event.

Topside came up with an elegant way of deciding what was a “trans” book: Did it have more than one trans person and did they talk to each other about something other than trans medical shit? Not all of the books I’m writing about here meet those criteria. Stratis, Boylan, and Norris center a singular trans character, real or fictional. It’s something I think of as an older model of transness in writing, in which transness appears as an anomaly in an otherwise cis world. The cis gaze has trouble imagining that we’re anything besides its other, existing just to affirm the norm. It can’t imagine we’re an entire culture to ourselves.

The other thing that had not a little to do with the expansion of publishing for trans writers was the success of Torrey Peters’s Detransition Baby, published by One World in 2021. Peters’s brilliant move was to use the genre conventions of the “divorce novel” popular with exactly the kind of educated, affluent white women centered in commercial fiction publishing. Peters’s insight was that divorced cis women, like trans women, confront a rupture in the narrative of their lives and have to make another one. The detransitioner of the title brings the two worlds of experience together.

Peters’s second book, Stag Dance (Random House), collects the novella-length work of the title with some of her earlier stories, which were not published by Topside but are marked by her encounters with that scene. Peters’s work is often about the difficult, messy side of transsexuality—the weird gender feels, quirky sexualities, dysfunctional relationships, inter-trans jealousies. In contrast to Boylan, these stories show trans people as rounded humans, flaws and all. Like Thornton, she is interested in the difficulties trans people can have with each other. The cis gaze structures how we perceive each other too.

Grouping these earlier stories with the new Stag Dance novella highlights another Peters quality: the way all her work plays with genre conventions. There are stories here that take on science fiction, horror, even young-adult fiction. Stag Dance itself is a western. It’s about lumberjacks. It’s a first-person story told in a convincing lumberjack argot. I’ve heard Peters read from this work and she really pulls off the voice.

The stag dance of the title is arranged by the boss of the timber camp to head off dissent. Anyone at the all-male camp who wears a triangle of fabric over his crotch signals that she may be courted as a woman for a period up to and including the dance. Such things did happen; the frontier was alive with all kinds of sexualities and gender that was more heavily policed in metropolitan centers.

The story turns on the jealousy of the narrator for another in the camp. The narrator is a big, tough man, strong and skillful with the axe, or at least that’s how they present themselves and how they are perceived. They discover, once the stag dance is announced, that he might somehow be a she.

Her attention turns to another in the camp who appears more outwardly feminine, and of whom she is jealous, although she will come fitfully to see that being more outwardly femme comes with its own risks and limits. Peters: “What if this saucy and glint-eyed seductress who bestowed and withdrew favor with a haughty glance was yet a green youngster playing at assuredness while barely negotiating the predations of the camp jacks?” Then suspicion intrudes into her feelings again: “But then I considered, equally, how a true seductress would wield artlessness with artfulness.”

It’s a brilliant feat of imagination, both in the way it invokes (something akin to) transness in the historical setting, and for the way it deals with the complexity of intra-trans encounters. The cis gaze, which sees us all as other, also makes us other to each other.

There’s something so bittersweet in this springtime for trans writers. Publishing lags a bit behind the times. For mainstream publishers, maybe it seemed like we were the next thing to add to the diversity playlist in the search for a market. The Great American novel by the Great White Man just isn’t a thing anymore. No matter how much hype the last Cormac McCarthy books got, not many people bought them.

The decline in the authority of the author is not a bad thing. That authority was premised on the assumption that “the others” didn’t read, or if they did, their (our) critical perspective wouldn’t matter. McCarthy could cartoon transness in The Passenger, as David Foster Wallace did in Infinite Jest, because in the synoptic world of the Great Novel we’re just emblems, incidentals, props.

The undoing of the authority of the author proceeded through the dissent of women readers, nonwhite readers, queer readers, and the formation of counter-literatures. Some of which, with some adaptation, became components of a replacement version of commercial literature. One can see the inclusion of trans writers within the field of the literary as a late development in that cycle.

The question is whether it will survive the repressive turn that’s gathered speed and fury in recent years. Public libraries, public-school reading lists, and university courses that center Black or queer or trans writing are up for purging. It’s likely we’ll be pushed back out of public life. I’m not the only one who sees signs of that already.

The commercial publishers will be fine. They don’t like to talk about it, but the bigger ones have imprints under their umbrella that also publish more fascist-friendly books. Losses in the liberal bourgeois-literary imprints may be offset by boosted sales elsewhere. Let’s see if they are willing to keep publishing trans-authored books next season, and the one after that, if the climate of hostility to us continues to intensify.

I’m agnostic about whether trans writers should put their faith in commercial publishing. Certainly there’s been some fine trans books which have survived the market imperative and found readerships, although there are others one could point to that were compromised in the process and which publishers did not know how to market, or decided not to try. My own interest has been in ways of creating not just the writer and the writing but forms of publishing and circulation as a project of trans culture-making.

Which is why I’m interested in smaller presses. They’re doing so much! Also this spring, Greywolf is publishing Paul Preciado’s Dysphoria Mundi, and Feminist Press has (So What) If I’m a Puta? by Amara Moira. There are other books I could mention from both Nightboat and Little Puss. My hope is that there’s a little more agency and autonomy for trans writers at the smaller scale. Maybe not all of our stories and experiences can be contained in more conventional forms. Maybe we have more room to write for each other rather than for cis readers there. On the other hand, smaller presses have a smaller reach, and usually less generous terms for booksellers. Some are dependent on state and private nonprofit funding bodies and subject to the whims of their do-good agendas. We’ll know soon enough if the nonprofit industry is going to abandon us.

In this roundup, I’ve left out books by trans men, nonbinary people. I’ve left out genre fiction and poetry. I tried, but I did not even get to all the literary fiction and nonfiction books by trans women that have been announced. And then there’s a whole other community of self-publishing trans writers and their reading communities. There’s too much for one person to cover—at least for now. No matter what, trans people will keep on writing, and finding ways to connect to readers. We’re not going away.