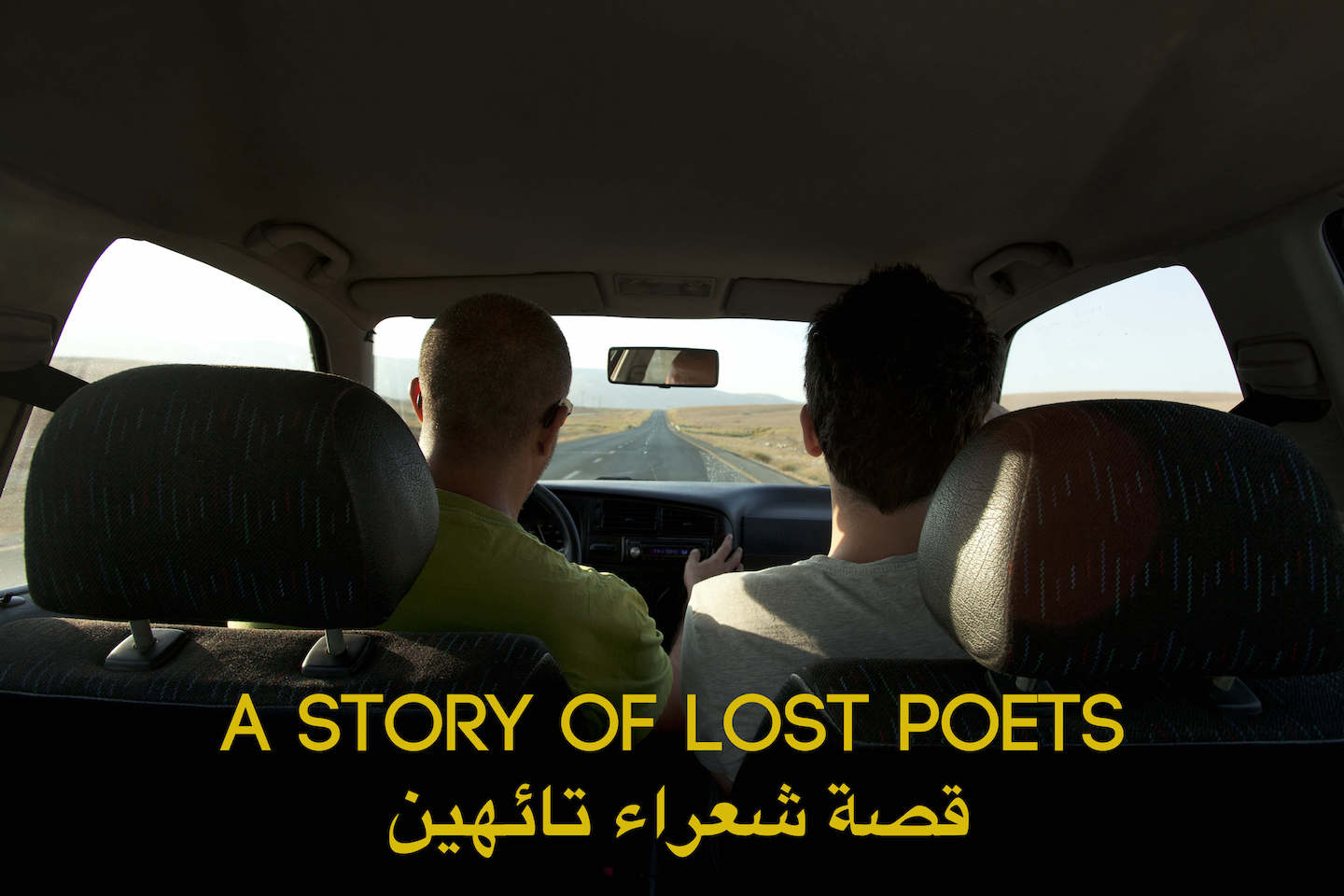

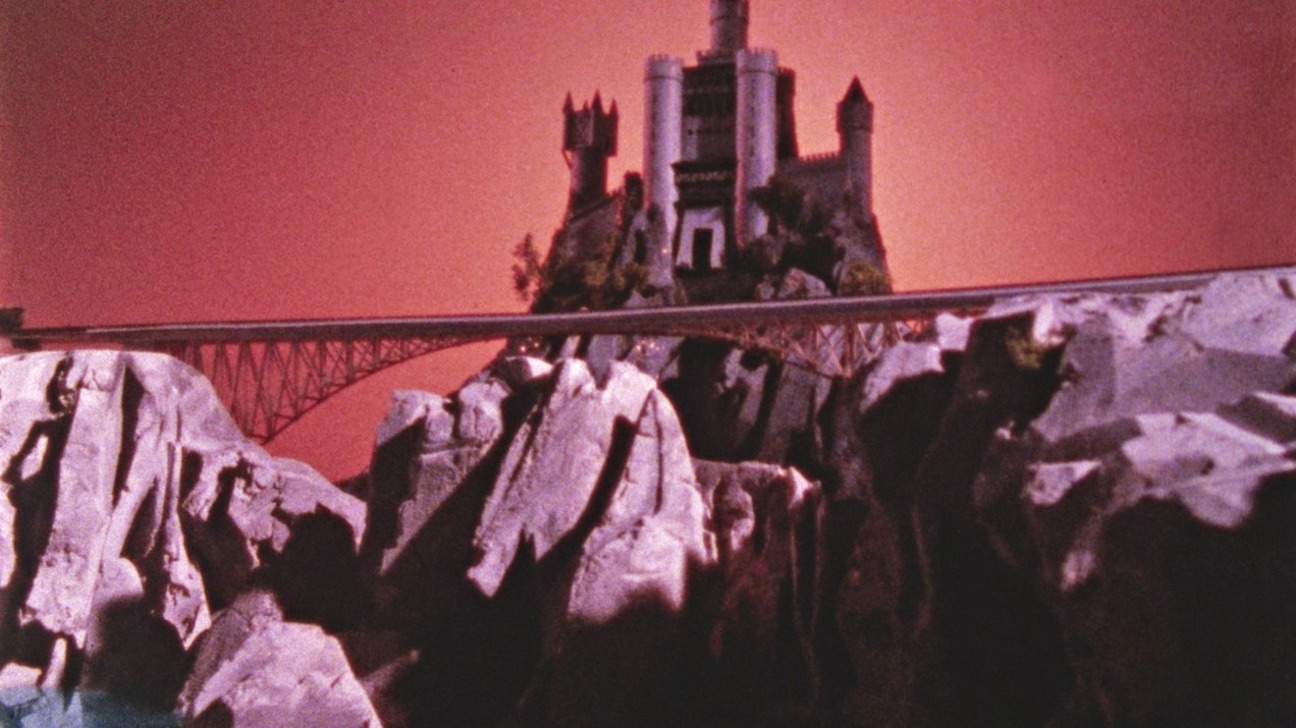

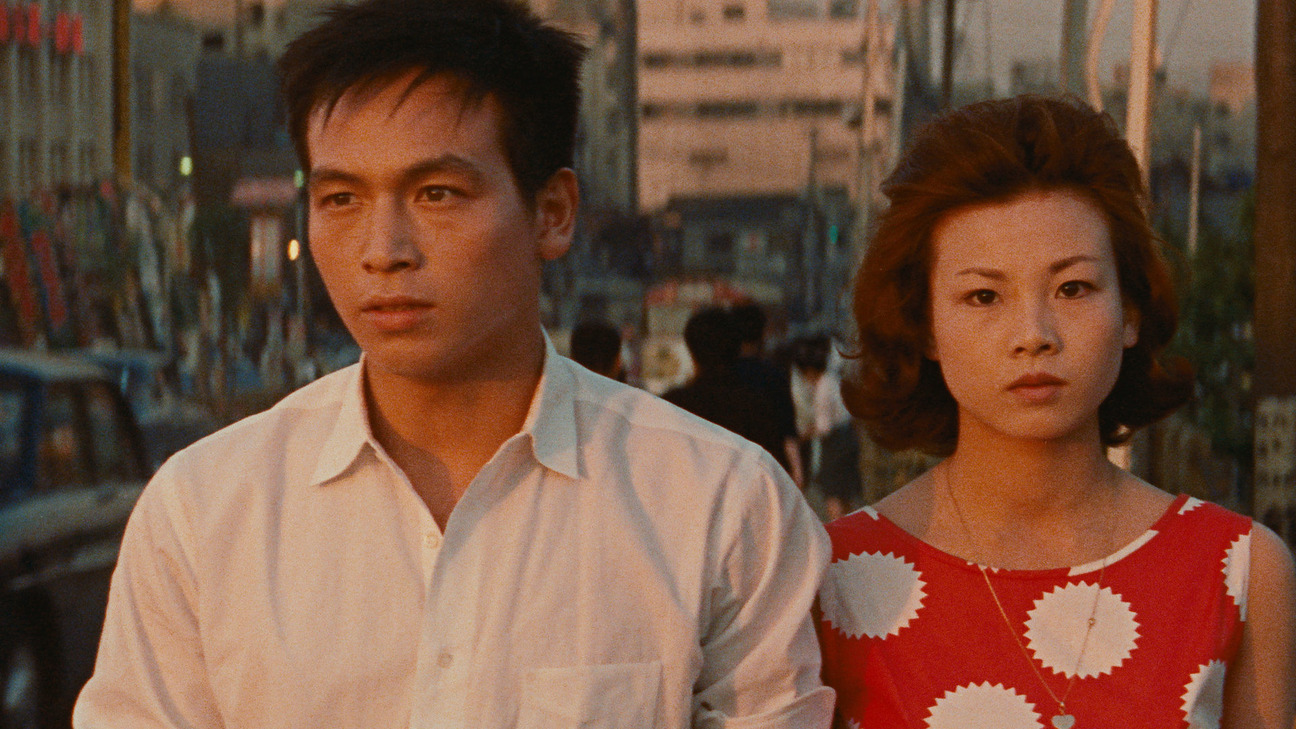

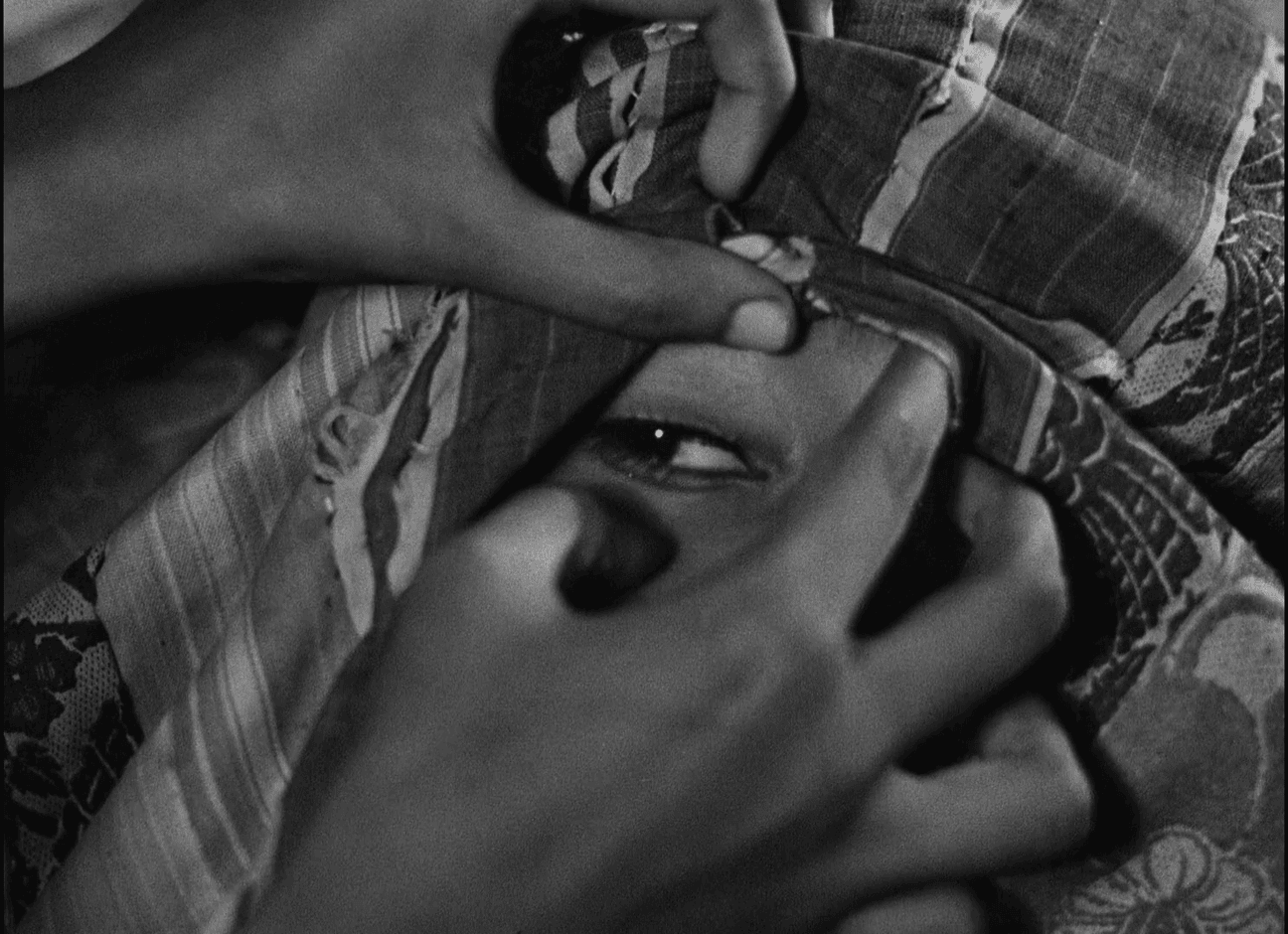

Oleksiy Radynski (still), Infinity According to Florian (2022).

More than a year ago, e-flux Screening Room hosted the New York premiere of Oleksiy Radynski’s Infinity According to Florian (2022), a film on the legendary Kyiv-based architect and artist Florian Yuriev. The screening was followed by a conversation between Radynski, e-flux Film curator Lukas Brasiskis, and the audience. The transcript of this conversation was edited for the present publication.

Question: How did you come to make a film about Florian Yuriev? His work and personality seem extraordinary, but I understand he wasn’t widely recognized in Ukraine until recently. How did you meet him, and what inspired the film?

Oleksiy Radynski: Thanks for asking. It’s really important to clarify because the film might give the impression that Florian was a well-known artist in Ukraine, but he wasn’t—at least not until very recently. For most of his life, he was almost completely overlooked. A few people remembered him, knew he was around, but he wasn’t widely recognized.

I first met Florian through my interest in experimental film. He had been involved in that world, too, though many people didn’t know it. About ten years ago, I got to know him mainly as the author of this architectural work—the Flying Saucer building in Kyiv. In one of our first conversations, he casually mentioned that, aside from everything else he was doing, he used to make experimental films. But, as he told me, these films were lost—nothing remained of them. That really intrigued me.

From that point on, I stayed in touch with him, trying to find any trace of these lost films. In the end, the footage you see in the film is what we managed to retrieve during production. Florian never completed any of his films—just like many of the other projects he started but left unfinished. So, what you see in the film are fragments of what survived.

Question: The film starts with exposition of Florian’s experimental films but shifts to focus on his architectural work. How did that transition happen, and why did you decide to emphasize his role in Kyiv’s architectural legacy?

OR: Yes, exactly. Our conversation with Florian began with the aim of exploring his experimental films, but over time, it shifted to focus more on his architectural contributions. Florian played a significant role in Kyiv’s architectural landscape, although that, too, was underappreciated for many years.

The venue you see in the film—the Flying Saucer, where his public lecture took place—was used for experimental music events, some of which were organized by my friends and colleagues. In 2017, it became a venue for the Kyiv Biennial, and this was when Florian gave his most important public lecture in Kyiv. That event was a part of the biennial, and it marked a turning point for both his recognition and the venue itself.

Around the same time, we discovered that a real estate developer had plans to redevelop the venue into part of a shopping mall. The events depicted in the film were among the last held there before these redevelopment plans began to take shape. These events, and the film itself, were also part of an effort to block this redevelopment and reinstate the original artistic function of the venue.

Question: Florian’s approach to architecture and society seems deeply tied to his unique worldview. How did his ideological stance influence your portrayal of him in the film?

OR: Florian had a very unique position towards ideology, and that was one of the most compelling aspects of his life. He lived through the Soviet system, where he was always on the margins, critical of the regime but still working within it. He endured both the constraints of Soviet control and later the challenges of capitalism.

What’s fascinating is that he never fully accepted either system. He was always an outsider, both under the Soviet regime and later under neoliberal capitalism. He remained incredibly critical of the new capitalist order that emerged in Ukraine after the fall of the Soviet Union, and towards the end of his life, he faced these harsh realities head-on. This sense of being caught between two ideologies—never quite belonging to either—is something I wanted to highlight in the film.

Question: Despite his age and the odds against him, Florian managed to resist the commercial forces trying to take over the space. Were you surprised by the outcome?

OR: Yes, I was. When I started working on the film, I was almost certain it would end badly for Florian and the space he was defending. I thought the forces against him were just too powerful. So it was remarkable to see him hold off the redevelopment, at least for the time being. It felt like a small victory, but an important one nonetheless.

Question: The way you filmed the architecture felt intentional, as if the buildings themselves were characters. Can you talk about the role of the landscape and architecture in the film?

OR: Yes, I’m glad you noticed that. The landscape and the architecture are key elements in the film. Even though the film is centered on Florian, I’m personally very interested in landscapes, especially in a cinematic context. Some of my previous films were almost entirely landscape-based, with no dialogue and no human presence—just the slow changes in the environment over time. With Infinity According to Florian, I felt it was necessary to focus more on Florian himself, but the landscape, especially the urban landscape of Kyiv, is still central. The transformation of the city, and how architecture reflects these larger changes, is something I wanted to convey through the imagery.

Question: The scenes with the workers outside the building were especially striking, almost like a mural. Was that contrast between the stillness of the workers and the chaos around them intentional?

OR: Yes, absolutely. Workers are such an important part of the film’s visual language. There’s a stillness to their presence that contrasts with the rapid changes happening around them. In some ways, they are a fixed point in the landscape, representing something steady and grounded while everything else is evolving and shifting. That contrast was definitely intentional.

Question: Florian’s Flying Saucer building is such an iconic structure. How did he come to design something like that under the Soviet system?

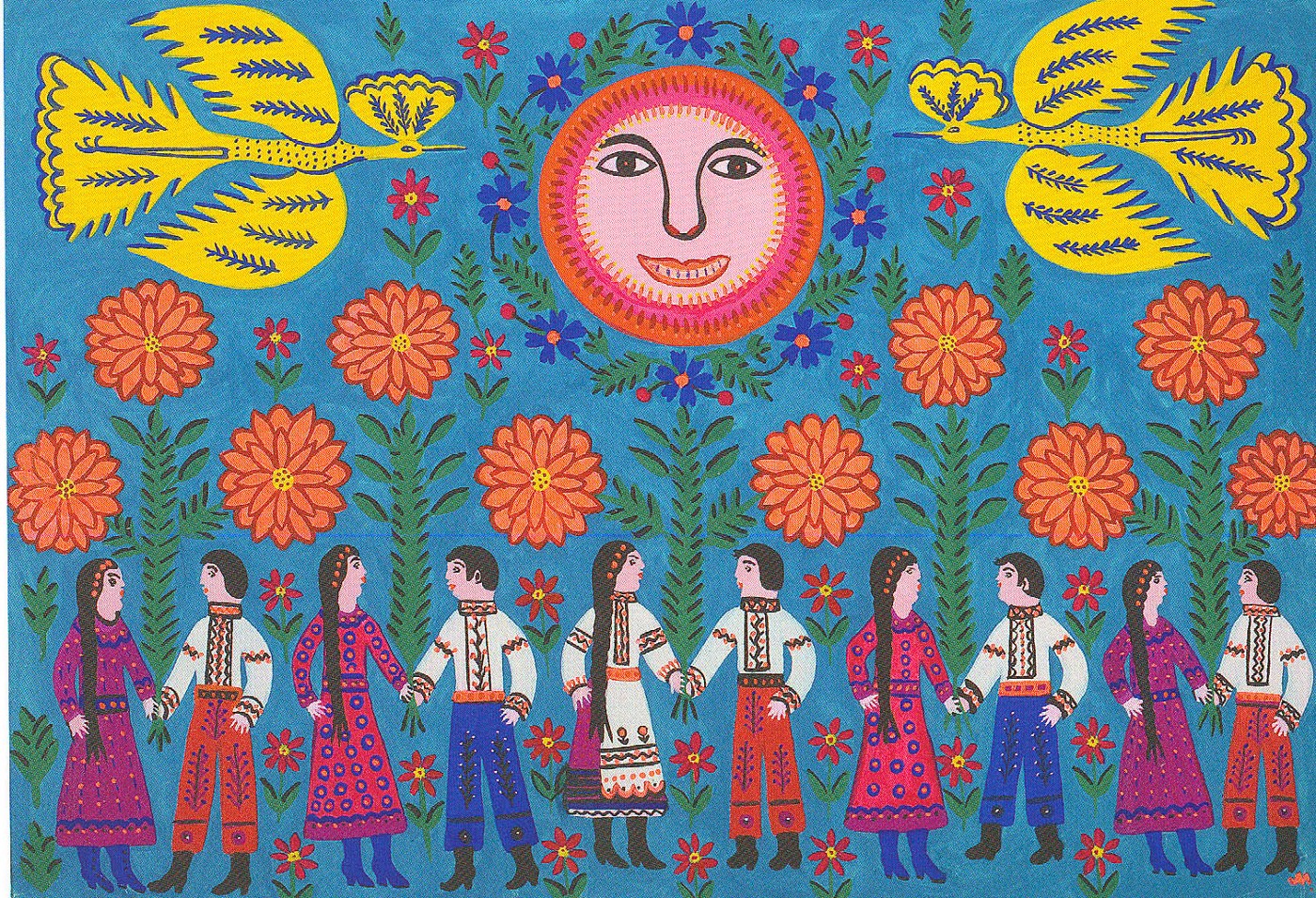

OR: The design of the Flying Saucer building was entirely Florian’s vision. He came up with the concept in the late 1950s, during a brief period of artistic openness in the Soviet Union, when avant-garde ideas seemed possible and state funding was available for experimental projects. Florian designed the building as a venue for synesthetic perception—a space where music could be experienced visually, through color.

Unfortunately, like many avant-garde projects of the time, it was quickly scrapped. What’s interesting, though, is that the KGB took over the project. They built the structure, but not as the theater Florian had imagined. Instead, it became a KGB facility, which is a strange and ironic twist.

Question: There was a scene in the film where a device was thought to be for surveillance but turned out to be for translation. Was that based on real technology?

OR: Yes, that was based on real technology. It’s likely that the device had a dual purpose—translation and surveillance. This kind of dual-function technology was quite common in the Soviet Union, where many things had hidden uses or could be repurposed for different goals.

Question: Florian’s ideas about art and nature were striking, especially his critique of anthropocentrism. Could you expand on his views regarding art and nature?

OR: Florian was ahead of his time in his thinking about nature and humanity’s relationship to it. He was deeply influenced by humanist and Cosmist ideas, which were part of the broader avant-garde movement he was involved in. He always emphasized that his art was rooted in realism, but not in the traditional sense. For him, realism meant representing the underlying forces of nature, even in works that might appear abstract. He believed that art should reflect natural phenomena, and that’s why he never saw his work as purely abstract—it was always grounded in the real world.

Question: The film ends with a small victory for Florian, but do you think his story can be used as an example for preserving architectural heritage in Ukraine?

OR: I’d like to think so, but it’s complicated. The film ends on a hopeful note, with the redevelopment project frozen, but that doesn’t mean the battle is over. Even though the building was granted protected status, that doesn’t guarantee its preservation. In Kyiv, we’ve seen many so-called protected monuments destroyed despite their status. So, while the film has a kind of happy ending, the real story is still ongoing.

Question: You started to shoot the film before 2022. How has the Russian war on Ukraine affected the themes of architectural preservation and capitalism that you explore in the film?

OR: The war has had a massive impact. One of the early outcomes of the Russian invasion was the temporary detainment of the real estate developer involved in the project, who is essentially a Russian oligarch. However, like many things during wartime, the situation remains unclear. Developers often see war as an opportunity to exploit destruction for profit, and the real estate situation in Kyiv has been chaotic since the invasion.

Question: In your 2023 short film Chornobyl 22, you turned your focus on Russian soldiers on Ukrainian soil at the start of the invasion. How did making this film during the early stages of the war influence your approach to storytelling, and what does it mean to create films in such urgent circumstances?

OR: Like most of my fellow filmmakers, since the outbreak of all-out Russian war on Ukraine in 2022, I have been seeking to contribute my skills as a documentarian towards Ukraine’s resistance. During the early stage of the invasion, together with my partner and producer Lyuba Knorozok, we joined the Reckoning Project, a media initiative aimed at documenting Russian war crimes in Ukraine and help ensure accountability for their perpetrators.

The war crime I initially focused on was the Russian military takeover of the Chornobyl nuclear power plant, the site of the worst nuclear disaster in history, located not far from Kyiv. At first, this was not meant to be a film, rather a war crime documentation process. I’ve conducted dozens of interviews with the survivors of the Russian occupation of Chornobyl, mainly the personnel of the nuclear plant, according to strict legal protocols that would enable their future use in court. These interviews were also filmed, and as we started to collect additional evidence by going to the newly de-occupied Chornobyl Zone, it became clear that they were going to be a film.

So, this documentary now has a life of its own, but it’s still part of the forensic process, aimed at the punishment of war criminals. For now, based on the evidence we’ve collected, two of the top Russian commanders in charge of the Chornobyl occupation were added to the EU sanctions list.

Q: Now that the war has entered its third year, how has your approach evolved? What does the role of immediacy mean for a Ukrainian filmmaker at this point, and how has the continued conflict shaped your practice over time?

OR: I guess that for every particular filmmaker, the role of immediacy differs on an individual level, but there’s a universal urge to contribute to Ukrainian resistance in whichever way possible. Many of my colleagues had joined the army, and some of them had unfortunately perished on the battlefield.It seems to me that as the war drags on, it’s important to supplement the immediate, reportage-based approach of the early days of the invasion with a more analytical stance. It is also important for us as Ukrainian filmmakers to go beyond the representation of the victimized side of this war, even though documentary work with Ukrainian communities will still be crucial. I think that Ukrainian filmmakers now have a duty to cinematically dissect our adversary—namely, the Russian society that has now descended into full-scale fascism. I guess Ukrainians are quite well-positioned to analyze the debacle that is today’s Russian Federation: as the former subjects of this empire, we are able to understand it both as insiders and as outsiders.

This is particularly important in the context of an abject failure of (almost) every Russian filmmaker and intellectual to engage critically with the war that their country had unleashed. Russian culture is now completely devoid of its most important function that actually made it what it was: its ability to provide ideas and tools against tyranny. This function has to be taken on by someone else if we are serious about defeating this fascist monster. I already see some really interesting examples of Ukrainian filmmakers analyzing the Russian society in ways that no Russian filmmaker is able to do at the moment. The recent documentary Intercepted (2024) by Oksana Karpovych is of course the most important example. Recently, I’ve completed my modest contribution to that discourse: a short, found-footage film Where Russia Ends (2024), dealing with Russian settler violence in the occupied indigenous lands. My new film that I’m now working on is an attempt to analyze the Russian military machine, which is much-feared but ultimately dysfunctional.