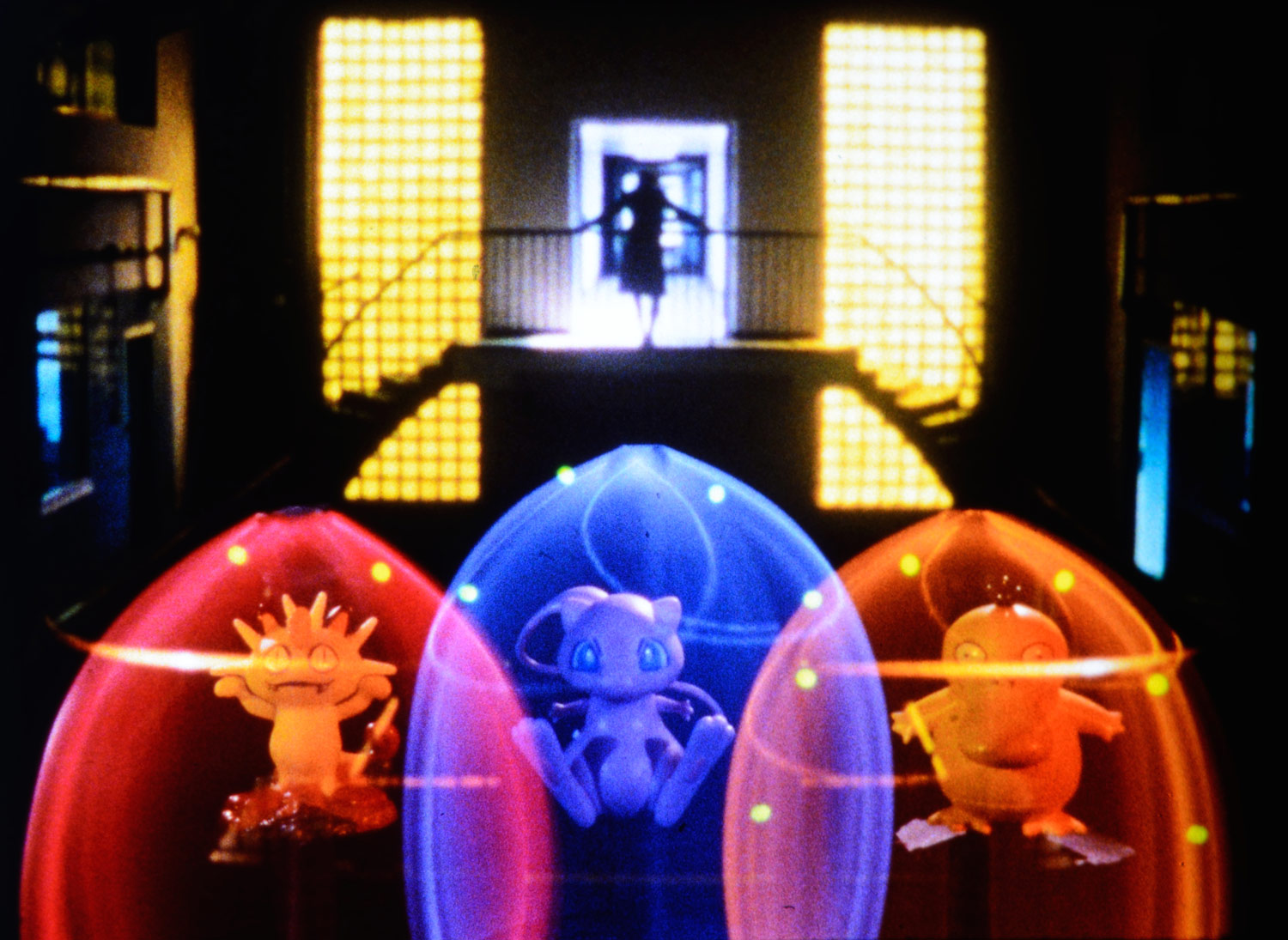

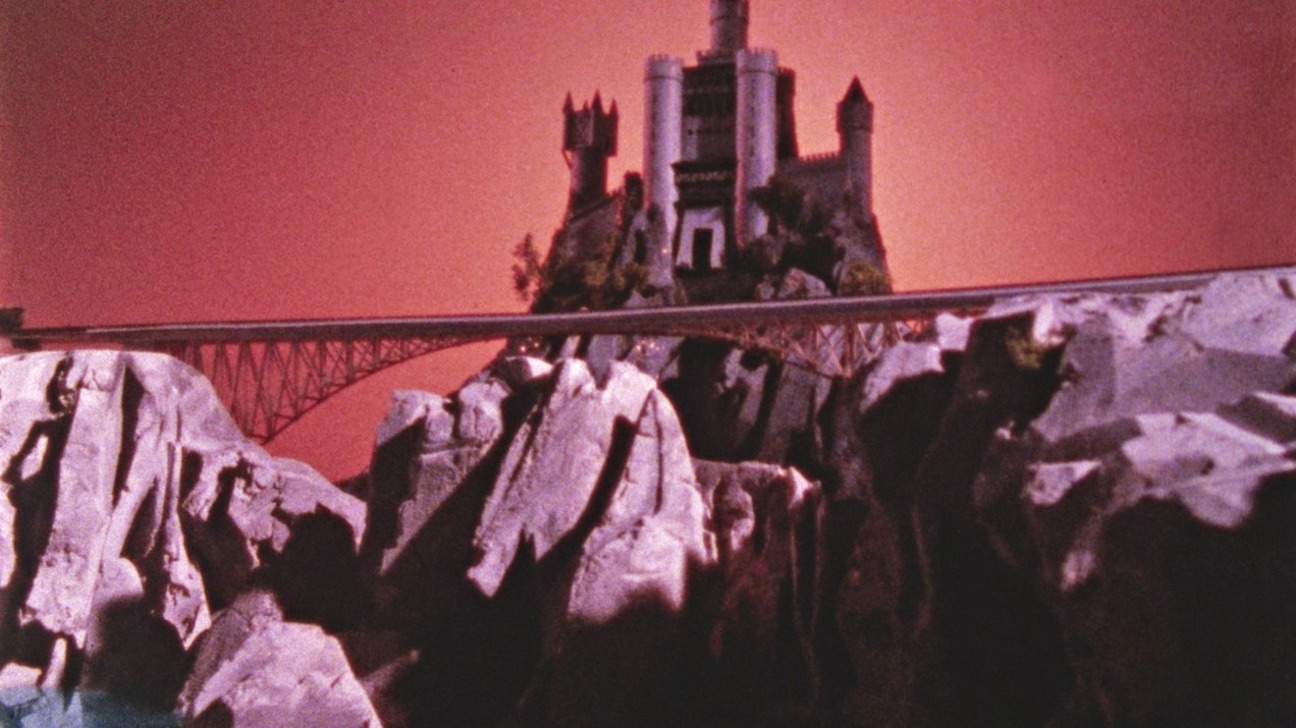

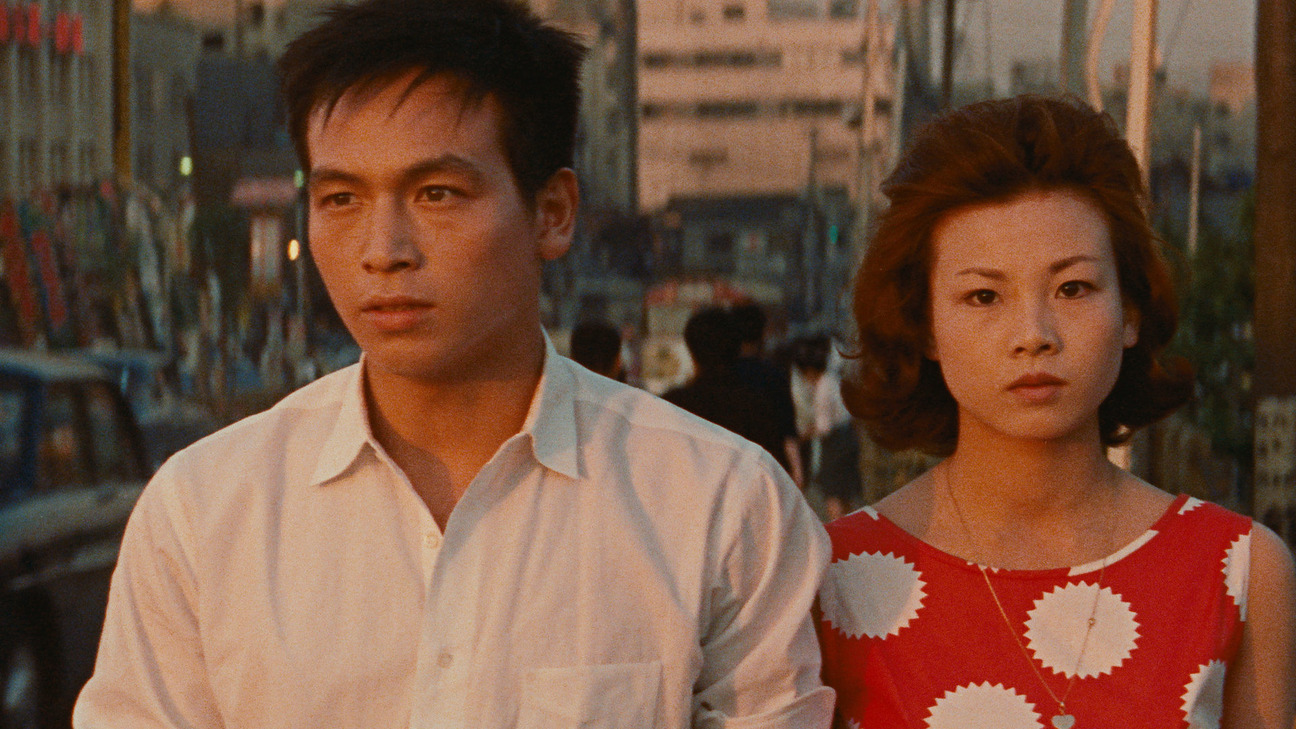

Still from the trailer for Barbie, dir. Greta Gerwig, 2023.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock for the past few months, it’s likely that you’ve already seen Barbie or at least watched the first trailer of the film, released a few months ago. In this short sequence, which turned out to be the film’s prologue, Greta Gerwig pays homage to 2001: A Space Odyssey. We see a group of little girls, in a Kubrickian prehistoric veld, playing with plastic dolls. These girls, who look like they date from the Great Depression, seem to have learned from a very young age to identify with the role that patriarchy has assigned to them: mothers and caretakers of the domestic space. It is when, not the monolith from 2001 but a statuesque woman with the features of Margot Robbie, suddenly appears that something cracks: the little girls are bewitched by this alien presence and begin to vehemently destroy their old dolls. Nothing will ever be the same again: the era of Barbie has begun.

Barbie, however, is not only beautiful, cool, and able to emancipate those little girls from the petty domestic fantasies that entrap them. She is also the embodiment of the object of desire (or at least a certain desire: male desire). Her appearance is also a metaphor for the moment when sexuality enters a little girl’s fantasy. But what kind of sexuality is this? On the one hand, Barbie dresses in skimpy clothes, is curvy, and has an ideal model body (this is what the film calls “Stereotypical Barbie”). On the other, something is missing, and that is her vagina, as Margot Robbie shouts to an embarrassed group of construction workers on Venice Beach. It must have happened to everyone when playing with Barbies, Kens, or similar toys of the time, like Big Jims: we would strip off their clothes to see what was underneath. And of course, the result could not but be disappointing: there was nothing there.

Since Greta Gerwig’s film makes extensive (and intelligent) use of the problem of Barbie’s missing genitalia, it is impossible not to think—right from that homage to 2001: A Space Odyssey—about Freud and the problem of how children deal with the distressing experience of discovering sexuality. Indeed, the discovery of sexual difference has always been, since Freud’s early texts, one of the most delicate and complex issues in psychoanalysis. The Freudian position is well known, and still sounds scandalous even to our emancipated and disenchanted ears: children at first do not know that there is a difference in the anatomy of the sexes, and therefore imagine that everyone—male and female—has a penis. Here it should be noted that Freud does not say that what is believed is that males and females are not different from each other, and therefore there is only one gender, neutral and indifferent. He says, rather, that males and females have a male sex. It is what Freud called—with an expression that’s difficult to use today without some embarrassment—the “primacy of the phallus”: even before experiencing empirically the true anatomy of males and females, children universalize the presence of the penis (or as Lacan would later say, partially detaching it from anatomy: the phallus). So why did Freud decide to elaborate a theory that at first sight seems so absurd? Why not simply say that the child is traumatized by the discovery of the existence of two anatomical sexes, rather than that the child believes that someone’s penis has been cut off?

The castration complex, as Freud would later call it, is indeed a myth: it is the foundational myth of the narcissistic construction of the child and their relationship with sexuality. Through the concept of the phallus, Freud did not want so much to affirm the primacy of male over female sexuality (although this was, inevitably and unfortunately, one of the most problematic legacies of the theory). He wanted instead to introduce a principle: the discovery of sexual difference is not about a world where two positive differences, such as male and female, peacefully coexist, but rather about a hole dug in reality. Sexuality introduces an absence into the fullness of being. It separates reality from itself. It makes reality miss something. That is why, for Freud, the phallus can only be perceived through its disappearance (literally: the girl because she does not have it; the boy because of the anxiety of being deprived of it). But the point of this concept goes beyond its literal formulation. The castration complex introduces a new register of experience: the child is not so much aware of the existence of a real anatomical difference, but of the fact that reality is traversed by an absence. This is what is at stake in the experience of the discovery of sexuality: the discovery of something that digs a hole in the edifice of existence.

What does this all have to do with Barbie? One of the clearest clinical confirmations of the castration complex (or, if you will, of the discovery of sexual difference) is that the child, even when facing empirical evidence of the anatomical difference between the sexes, continues to believe that all human beings—in Freud’s terms—have a penis. Or, if we want to put it in our terms, that there is nothing missing from reality. The world is full, and everything is in its proper place. Isn’t Barbie the epitome of such a quintessential fetishistic denial?: “I know very well that human beings are divided into male and female, and not everyone has a penis, and yet in my unconscious, I keep entertaining the fantasy that this is not true.” Literally: I am well aware that Barbie is a sexualized, seductive female (isn’t this what her appearance precisely communicates?), yet if I try to see what is there under her panties, I find nothing that suggests that she has a sexed body. In short: I want sexuality, but without having to really accept it.

The first fifteen minutes of Barbie provide a perfect psychoanalytic treatise on what a world ruled by fetishistic denial looks like: perhaps never before have we seen, portrayed onscreen, a world where enjoyment and sexuality are so glaringly absent. For Barbie, every day is the happiest day of her life: her breakfast is always perfect, and no one ever has to cook it (it magically cooks itself, since no one has to work in Barbieland); the water in the shower is never too hot or too cold; and Barbie doesn’t even have to climb down stairs to get to the ground floor—she just floats. The most hilarious dialogue in the film occurs when Ken says to Barbie, at the end of a party, “I thought I might stay over tonight. We are boyfriend and girlfriend.” To which Barbie replies, “Why? To do what?” To which he laughingly responds, “I’m actually not sure.” Everyone in Barbieland is beautiful and has a perfect body, but it’s as if they have never learned that sexuality exists.

Precisely because sexuality concerns the presence of an absence and thus a radical imbalance in existence, it cannot but be connected with death: a sexed body is also a body inhabited by its being-toward-death. That’s why the first emergence of castration anxiety in Barbieland has the form of a “thought of death,” which is nothing other than a perturbation or out-of-jointness of reality: the body is no longer perfect (the feet flatten); the water in the shower is either too hot or too cold; the pancake has been burned and the milk has expired; and when Barbie floats to the ground floor, she falls down. In short: “I am well aware that human beings are divided into males and females, but in my unconscious, the fantasy that supports the denial of this difference is cracking.” In other words: symptoms appear, and although Barbie tries hard to suppress them, they become stronger and stronger until they are unbearable. (The scene-homage to The Matrix is probably the most brilliant moment of dialogue in the film, not to mention one of the best representations of how humans are driven by a will of not-knowing.)

The reality check comes when the fetishistic and desexualized world of Barbie is contrasted with the real world: a world that, unlike Barbieland, is invaded by sexuality. In this real world, males and females do not cooperate in the construction of an anxiety-free idyll. They enter into competition with each other, do harm to each other, and look at each other in a threatening and harassing way. Of course, historically this is the world of patriarchy (whose twilight we all hope is near), but it is also and more profoundly the unbalanced and out-of-joint world where life is caught in the craziness of the symbolic, of language. So what should we make of our fetishistic fantasy of Barbieland, where sexual difference does not exist and where everything works perfectly? Doesn’t becoming an adult also mean giving up one’s fetishistic denial and coming to terms with the fact that symptoms, unfortunately, will not go away?

This is where Gerwig’s film hesitates, for while it does not give up on saving Barbieland and making it once again what it was at the beginning of the film, it ends with Stereotypical Barbie finally deciding to become a sexed being (thus abandoning Barbieland). It is as if the fantasy of Barbieland must be preserved—as is shown by America Ferrera’s character, who as a middle-aged woman frustrated by work and unhappy with her family starts to play again with Barbies well into her forties, like she was still a child. But at the same time, something of that fantasy world must be abandoned, as Margot Robbie’s character shows (she in fact gives up Barbieland precisely because she feels too out-of-joint). This hesitancy is symptomatic of a film that wants to have its cake and eat it too: it tries to reconcile being one big Mattel advertisement, while also critically distancing itself from it. The film is perhaps also symptomatic of a contemporary ideology that is full of infantilizing cultural objects deprived of the disturbing dimension of sexuality. Thus the film does not know what to do with sex—this was Steven Soderbergh’s brilliant critique of superhero movies. Perhaps we really should go back to Freud and the problem of castration: for while it is true that the phallus will never become a presence (as patriarchy thinks), it is also true that the problem it poses will not be gotten rid of so easily.