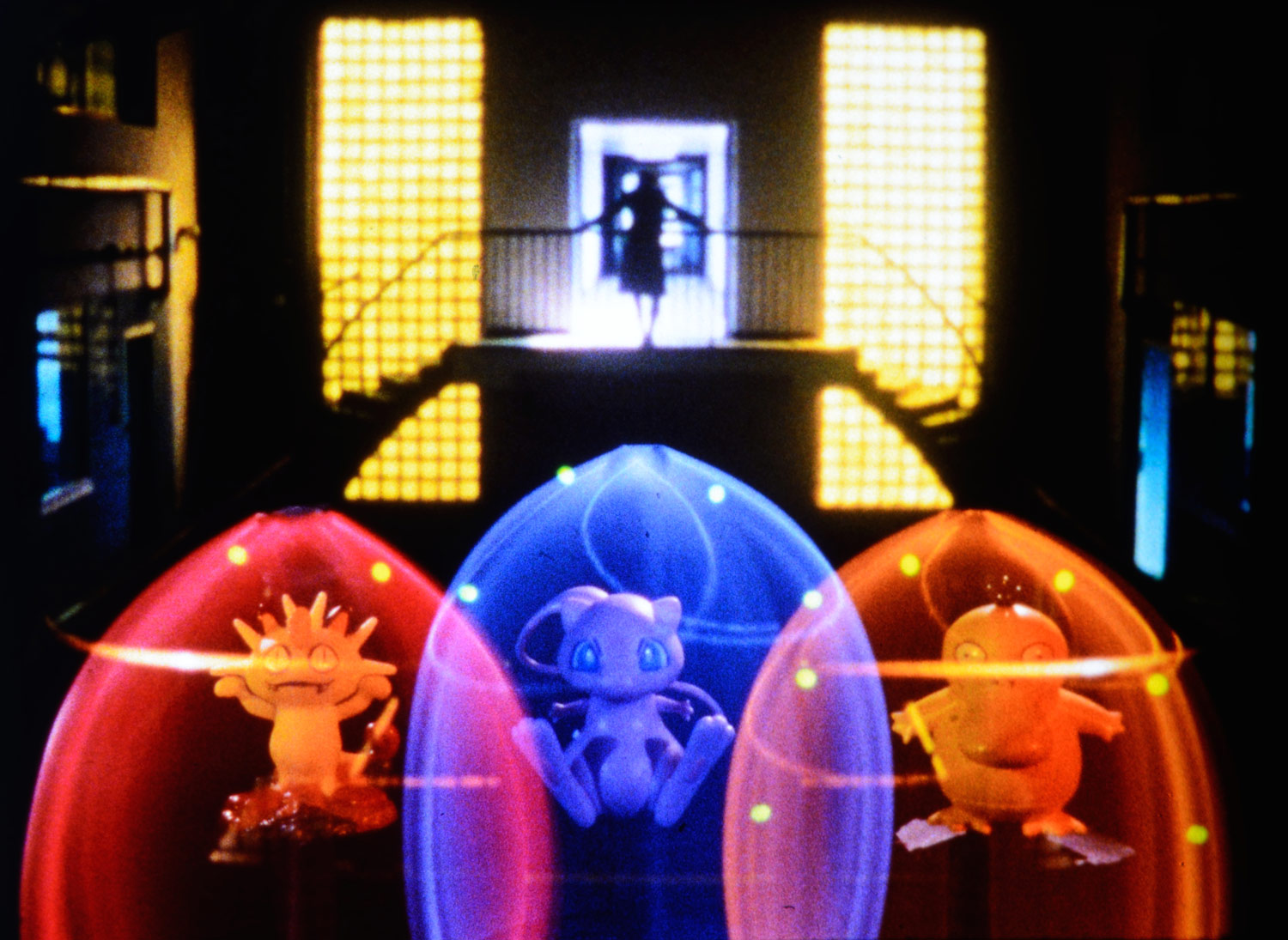

Film still from Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Kuru otlar üstüne (About Dry Grasses), 2023.

Film festival juries are a strange thing. Even though they are composed mostly of industry professionals and artists who have an impressionistic and superficial understanding of film history, and little to no knowledge of aesthetic concepts (and are not film scholars or intellectuals), they are nevertheless called upon to give out awards that spark significant processes of canonization, and of cultural and social recognition. This is why, despite their unreliability—and questionable oscillations in the recent past—it’s difficult to underestimate their impact.

As I discussed in my first dispatch from Cannes, processes of cultural canonization have come increasingly into crisis. We are now in a cultural landscape where so many different canons coexist, with so many different niches and languages for analyzing and discussing films, that jury verdicts are even more idiosyncratic and subjective than in the past. But perhaps, in an even more significant way, what has happened in recent years is that these multiple “canons” are increasingly oblivious to each other; they belong to different worlds, no longer speaking to each other or even speaking the same language. This renders inoperative the modernist dialectic between canon and avant-garde, where provocation, critique, and the questioning of the canon used to go hand in hand with its recognition (even as a negative point of reference).

To this we should add a relatively recent phenomenon: the debate over whether film festivals should privilege films for being generic cultural objects (i.e., ideological formations) that reflect processes of transformation in society, or should primarily look at the form of their representation and the specificity of film language. Probably—although we can’t know for sure the reasoning behind awards—in the first group we would find films such as Adina Pintilie’s Touch Me Not, which won the Golden Bear in Berlin in 2018 with a very interesting but formally traditional documentary on sexuality and disability; or Laura Poitras’s All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, winner of the last Venice Film Festival; or Fahrenheit 9/11, which famously won the Palme d’Or in 2004 (in an edition of Cannes where Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Tropical Malady, Wong Kar-wai’s 2046, the Coen brothers’ Ladykillers, and Olivier Assayas’s Clean were all in competition). In the second group would be Palme d’Or– and Golden Lion–winning directors like Nuri Bilge Ceylan, Lav Diaz, Theo Angelopoulos (for Eternity and a Day from 1998), and Michael Haneke.

This year the Cannes jury, chaired by Ruben Östlund (who won the Palme d’Or twice in recent years, with the divisive and much-discussed films The Square and Triangle of Sadness), decided to award the Palme d’Or to Anatomie d’une chute (Anatomy of a Fall) by Justine Triet—the fourth Palme d’Or won by a French film in the last ten year (while there were only five French films awarded this prize in the fifty previous years). With Triet’s emphasis on the radical heterogeneity between real and procedural truth—in her film, a husband dies after falling from a balcony, and we never know whether he committed suicide or was killed by his wife, who was trying to divorce him—she puts ethics as well as truth out of the picture, in a way that is consistent with Östlund’s cynical and postmodern approach to filmmaking. Jonathan Glazer’s provocative The Zone of Interest, on the other hand, which received the second-most important prize, the Grand Prix of the Jury, juxtaposes an idyllic bourgeois family and the horror of the extermination of the Jewish people. The film, which tells the story of a Nazi commandant and his wife who live in a villa next to Auschwitz, proved to be foreign to the decades-long debate on the relationship between the image and the extermination camps (contrary to what László Nemes did with his astonishing The Son of Saul in 2015). While these two choices in a sense fall somewhere between a formal and a political dimension of representation, their divisiveness and over-the-top provocativeness (especially in the case of Glazer, one of the most heatedly discussed films of the festival) show once again the difficulties of contemporary processes of cultural canonization.

For all these reasons, in this second part of my dispatch from Cannes I have decided not to directly discuss the films awarded by the jury. Instead, I will focus on three films around which the elaboration of a critical discourse, I believe, would be most interesting and productive.

The first one is Kuru otlar üstüne (About Dry Grasses) by Nuri Bilge Ceylan. Ceylan won the Palme d’Or in 2014 for Winter Sleep, but he is probably best remembered for 2011’s Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, one of the most recognized and discussed films of recent years, and one of the defining works of contemporary auteur cinema. Across three decades Ceylan’s cinema has developed one of the most pertinent reflections on the relationship between word and image, with an emphasis on writing and dialogue that is unusual compared not only to the majority of films today, but also to the way script-writing works in contemporary prestige TV. Often his exceedingly long dialogues have such an extraordinary literary quality that his films end up being astonishingly dense despite the accessibility and clarity of his stories. Because of his references to Chekhov and to the tradition of nineteenth-century literature, Ceylan has often been considered (and even dismissed by some) as a director who comes perilously close to neoclassicism or mannerism. However, in his new film—which is among his most original—Ceylan delves more explicitly than ever before into the territories of modernism, even featuring a sequence where a character breaks the fourth wall and enters the set (only to return to the fiction of the story after a few seconds).

Kuru otlar üstüne takes place, like many of Ceylan’s films, in Eastern Anatolia, not far from Turkish Kurdistan, even though the events could just as easily be imagined in other historical or geographical contexts. Shaped by a series of dichotomies—urban and rural, individual and community, good and evil, masculine and feminine—the film’s protagonist, Samet, is a classic filmic figure: neurotic, indecisive, and paralyzed by the different paths his life might take. He is stationed in a rural school, where he is finishing his fourth year of compulsory service as an art history teacher before moving to Istanbul. Samet is an inept, cynical, and manipulative character, absolutely unsympathetic. But then he is confronted by a single “utopian” moment that might suspend the chronic indecision of his life: he develops a friendship, tinged with seduction, with Sevim, the best student in his class, who is ten or eleven years old. Samet brings her small gifts and often chitchats with her in his studio after class. When the school principal and the local school board investigate him for “inappropriate conduct” (here Ceylan gives a hint of the pathologies of Erdoğan’s regime), Samet’s life begins to crumble. Things get even worse when he attempts to seduce Nuray (played by Merve Dizdar, who won the award for Best Female Performance), a leftist colleague who questions his selfishness and individualism. In Samet’s projection onto others of the uncertainties of his life, it is as if he experiences not only the profound contingency of his own existence, but also how his narcissism is fundamentally based on a structural rejection of death. (In this he is a quintessential obsessional neurotic.) The last act of the film—a soliloquy with an overtly philosophical tone—constitutes one of the peaks of Ceylan’s cinema and is a remarkable moment of self-awareness by the director.

One of the most anticipated events of Cannes 2023 was the premiere of Cerrar los ojos (Close Your Eyes), the new film by Spanish director Victor Erice, which comes thirty-one years after his previous film, El Sol del Membrillo (The Quince Tree Sun). Erice, who is now eighty-three, represents something of an underground myth of twentieth-century European cinema; suffice it to say that his feature El espíritu de la colmena (The Spirit of the Beehive) was made when Franco was still in power in Spain, and that Cerrar los ojos is only his fourth film. An extraordinary reflection on memory and cinema, the new film reminded me of the opening sentence of Paolo Cherchi Usai’s Death of Cinema: “A civilization that is prey to the nightmare of its visual memory has no further need of cinema. For cinema is the art of destroying moving images.” Memory can only be based on selectiveness, and thus on erasure, forgetting, oblivion. The idea that everything can be remembered and therefore recorded—that nothing can ever disappear—is the nightmare of a civilization where time does not exist, and which therefore not only rejects the past as a place of disappearance but also the future as a place of transformation.

Cerrar los ojos is the story of a fictional Spanish actor, Julio Arenas, who in 1990, while shooting a film, disappears without a trace. Many believe that he died when an accident befell him by the sea; others, like his friend and director Miguel Garay, think he just wanted to start a new life. The tragedy returns as farce more than two decades later when the mystery of his disappearance becomes the subject of a cheap and exploitative TV show. It turns out that Julio is still alive but has lost his memory. (Is this amnesia the consequence or the cause of his decision to cut ties with the world?) He has been carrying signs of his past life (objects, photographs, and of course films and pieces of films) with him as if they were an external memory lying outside his body, while still being part of him.

By losing memory do we stop being who we are? Or is there something about us that is irreducible to memory, understood as the storing of past information and experiences? These are the questions that Julio’s neurologist asks himself in one of the film’s densest dialogues. It is what many families go through when Alzheimer or dementia strikes their loved ones. The problem of memory gets intertwined with that of identity: What happens to someone when the memories of their life seem to be completely “erased”? Is Julio still himself, or has he become someone or something else? What happens to a person when the content of their life disappears? And how do you interact with this person? Do you rely on the scattered pieces of memory that are left, or do you radicalize even more the heterogeneity of memory and subjectivity?

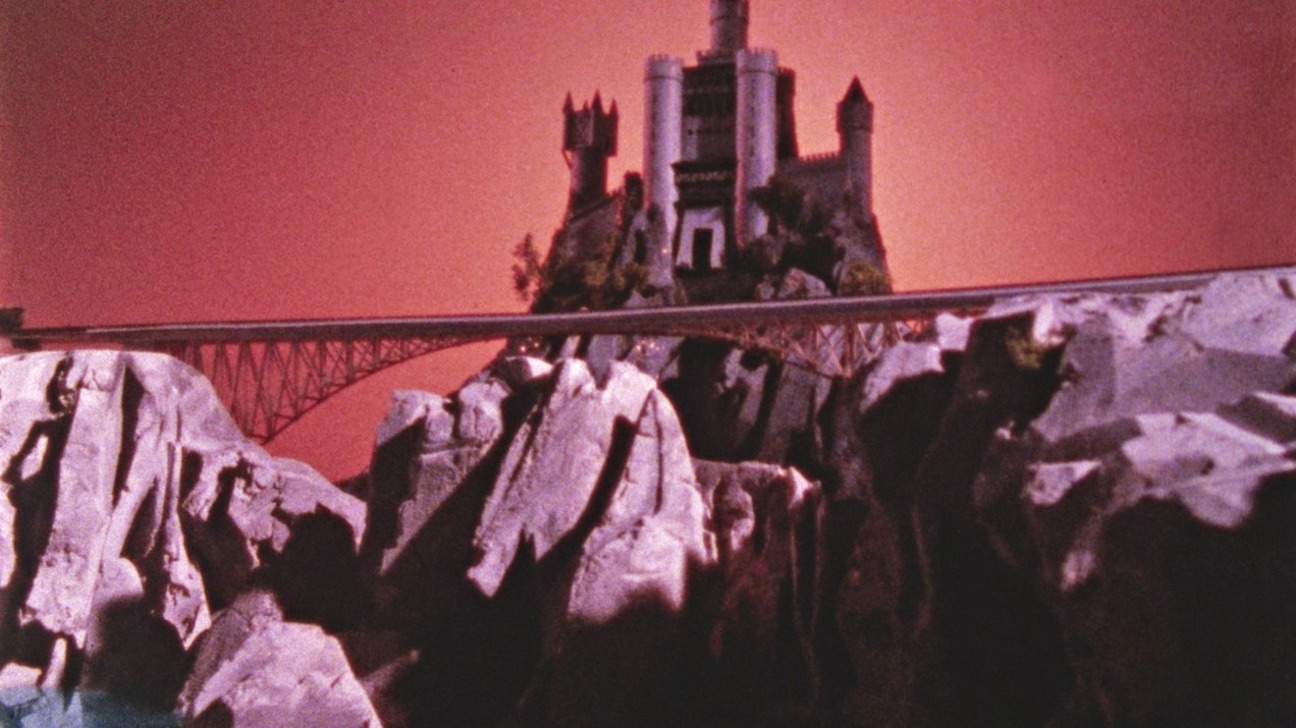

Cerrar los ojos features a film within a film: precisely the one from 1990 that Julio fled, which figures as the opening and ending sequences of Cerrar los ojos. The 1990 film is the story of a sad king (his mansion is called Triste-le-Roy, a name borrowed from Borges’s short story “Death and the Compass”) and his daughter, who has disappeared in China and whose gaze the king desperately needs (it is the signifier he lacks and around which his subjectivity revolves). In this paradoxical and Borgesian story of a missed gaze, the detective played by Julio is supposed to find the gaze and bring it back to the king at the end of the film. There are many biographical references here, and a complex intertwining of fact and fiction: on the one hand, Julio’s “fictional” memory of the film is an integral part of his life (the set photos and props are preserved as if they were real photos and real objects); on the other, the aborted film is also biographically reminiscent of El embrujo de Shanghai (The Shanghai Spell), which Victor Erice was supposed to direct at the end of the 1990s but was later directed by Fernando Trueba.

Yet the question which Erice seems to be pursuing in this film is more than anecdotal and is certainly not reducible to a postmodern game of confusion between reality and fiction. It concerns the problem of what an experience of subjectivity would look like if everything was forgotten. The gaze in its purest form is without past or future: it is, as Freud said of the drive, a zone of indistinction between the active and the passive, or between subject and object. It does not concern the act of looking at something but the cut of the eyes when they close or when they are fleetingly revealed by an oriental fan, as we see in the last scene of the film. Perhaps, the film seems to imply, this is the only possible way of looking at a world that is devoted increasingly to the religion of absolute memory and absolute recording, and is dazzled by the contents of images without being able to see anything anymore. Vision is a matter of looking with one’s eyes closed and finally being able to inhabit the miracle of a vision with no memory and no content. But in the enchanted world of the digital, no one seems to believe in this kind of vision anymore.

Another Cannes film that reflected on memory was Brazilian filmmaker Kleber Mendoça Filho’s Retratos Fantasmas (Pictures of Ghosts), which was among the most inspiring films of the festival. Presented in the Séances Spéciales section, it is a documentary dedicated to Recife, the director’s hometown and the backdrop of all his films. Like many other urban centers around the world, Recife is undergoing a radical and traumatic process of transformation due to gentrification and real-estate price inflation. Retratos Fantasmas is a sort of documentary spin-off of Filho’s Aquarius, which screened at Cannes in 2016. In both films, Kleber is obsessed with the places of cinema: at first with private places, such as his own apartment, where many of his films have been shot, especially during the first part of his career; and then with public places, like movie theaters in Recife, where his sentimental education as a cinephile (and then a filmmaker) took shape. Recife’s theaters and their underground crowd of projectionists, programmers, film enthusiasts, and owners are the core of the film. Kleber relies on a register that is ironic and effortless at the same time. He provides a glimpse of several decades of film-going history not only in Recife but in many other places that have constructed part of their collective sociality around public and community movie theaters.

Retratos Fantasmas is one of those rare films whose great achievement is that of developing a profound reflection while maintaining an easy and affable tone. The old inner city of Recife, like in many urban areas of the United States, has largely been supplanted by shiny new neighborhoods created out of nothing. But a few decaying public places remain, and Kleber interprets these as the impossibility of completely erasing the memory of urban space, which continues to resist in the form of a dark ghost. Similarly, what is the cinematic image if not memory embodied not by a conscious and willful agent but by an unconscious and repressed one? Memory but without a subject to remember it, as in Erice’s film? This is memory embodied not by the mind of a individual but by expired film stock, by an abandoned cinema in a decaying downtown in northeastern Brazil, or by the dry grasses of a provincial town in Eastern Anatolia, where an elementary school teacher goes to reflect on his own existence.