Christa Blümlinger, “Harun Farocki, circuit d’images” in Trafic 21 (Spring 1997): 44–49; “Harun Farocki, Bilderkreislauf” in Ärger mit den Bildern. Die Filme von Harun Farocki eds. Rolf Aurich and Ulrich Kriest (Konstanz: UVK Medien, 1998), 307–315 ; “Image(circum)volution: On the Installation Schnittstelle (Interface),” in Senses of Cinema; as in Thomas Elsaesser (ed.), Harun Farocki: Working on the Sight-Lines (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2004), 315–322; “Bild(krets))lopp. Om installationen Schnittstelle,” in OEI 37 & 38 (2008): 48–57.

Constanze Ruhm, “Hotel Utopia,” Summerstage Festival (Vienna, 1999).

For the haus.0-program of the Künstlerhaus Stuttgart, which was run by Fareed Armaly at the time.

Fareed Armaly and Constanze Ruhm, NICHT löschbares Feuer / Spuren der Inszenierung, exhibition brochure (haus.0 and Künstlerhaus Stuttgart, 2001).

“Fate of Alien Modes” was an exhibition I curated at Vienna Secession.

In Thomas Elsaesser and Malte Hagener, Filmtheorie zur Einführung (Hamburg: Junius Verlag GmbH, 2011), paraphrase.

Mark Rakatansky, “Spatial Narratives,” 1999 / “Räumliche Erzählungen,” translation and publication on the Künstlerhaus Stuttgart website (www.haussite.net/site.html), German and English text.

Harun Farocki in Fate of Alien Modes, ed. Constanze Ruhm (Vienna: Secession Wien, 2003).

In the anthology The Education Image (Das Erziehungsbild), eds. Tom Holert and Marion von Osten (Vienna: Schriften der Akademie der bildende Kunste Wien, 2010).

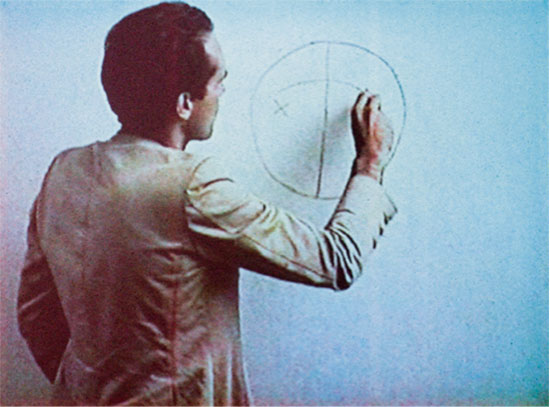

Harun Farocki and Hartmut Bitomsky, Eine Sache, die sich versteht, 1971.

Andrzej Wajda, 1958.

Translated from German by Leon Dische Becker.