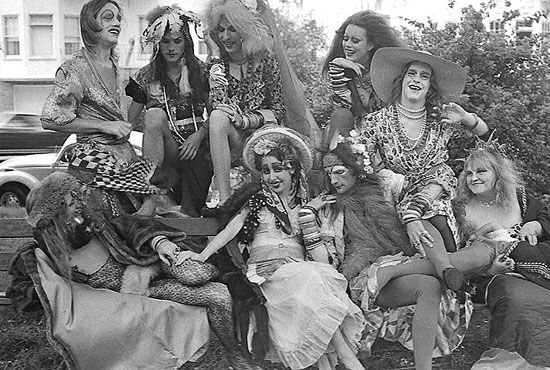

This history is presented in Bill Weber and David Weissman’s documentary The Cockettes (2002) as well as Joshua Gamson’s book The Fabulous Sylvester: The Legend, the Music, the Seventies in San Francisco (New York: Henry Holt/Picador, 2005).

See →.

See →.

Rachel Mason, interview with Bradford Nordeen, Bad at Sports blog (Nov. 4, 2011). See →.

See →.

Clips from The American Music Show can be found on YouTube at →. Thank you to Ricardo Montez for introducing me to the show.

I interviewed Sarolta Jane Cump by phone on March 13, 2013, and Cary Cronenwett and Gary Gregerson (aka Gary Fembot) by phone on March 14, 2013.

See →.

The ideas in this paragraph are developed in Greg Youmans, “Performing Essentialism: Reassessing Barbara Hammer’s Films of the 1970s,” Camera Obscura 81 (2012): 100–135.

José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia (New York: NYU Press, 2009). See also Jack Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011).

See →.

For Borden’s account of the production history of Born in Flames, see her interview with Jan Oxenberg and Lucy Winer,The Independent (Nov. 1983): 16–18. A special issue of Women and Performance dedicated to the topic of the film’s significance is due out later this year, edited by Dean Spade and Craig Willse.

See →.

See →.

See →.

Rebecca Solnit, “Image Dissectors,” in Radical Light: Alternative Film and Video in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1945–2000, eds. Steve Anker, Kathy Geritz, and Steve Seid (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), 16–18. See also Rebecca Solnit, “Diary,” London Review of Books 35.3 (Feb. 7, 2013): 34–35, →.