Thank you to Jenny Gil Schmitz, Emilio Silva Barrera, Carlos Slepoy, Luis Rios, Francisco Etxeberria, José Luis Posadas, Marcelo Esposito for all information relating to this issue and for their generous hospitality. This first part of the text owes very much to discussions with Eyal Weizman.

See Ernst H. Kantorowicz, The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Mediaeval Political Theology (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997).

See Giorgio Agamben’s The State of Exception and Homo Sacer. See also Foucault on biopower.

In a letter written in the 1950s.

G.W. Leibniz, Monadology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1898), 251.

Michael Grau, “Universalgenie Leibniz im Visier der Nazis,” Sept. 12, 2011, Berliner Morgenpost.

Michel Foucault, The Birth of Biopolitics (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave, 2008).

L. Ríos, J. I. Ovejero, and J. P. Prieto, “Identification process in mass graves from the Spanish Civil War,” Forensic Science International (June 15, 2010).

“Discovery of Kurdish Mass Graves Leads Turkey to Face Past,” voanews.com. Howard Eissenstat, “Mass-graves and State Silence in Turkey,” March 15, 2011, blog.amnestyusa.org.

Interview with Luis Rios, Sept. 12, 2011.

Thank you to Tina Leisch, Ali Can, Necati Sönmez, Şiyar, and many others whose names cannot be mentioned.

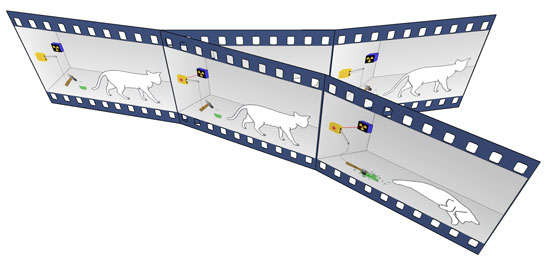

In the meantime, this text has been redeveloped into part of a joint performance with Rabih Mroué called “Probable Title: Zero Probability.” I am deeply indebted to Rabih’s contributions, especially in his brilliant text “The Pixelated Revolution,” which gives other examples of low-resolution evidence.

I discussed some examples of documentary pictures, mainly from Georges Didi-Hubermans essay “Images malgré tout,” in Hito Steyerl, “Documentarism as Politics of Truth,” republicart.net/disc/representations/steyerl03_en.htm.

See Jalal Toufic, “The Subtle Dancer,” p. 24: “a space that is neither two-dimensional nor three-dimensional, but between the two.” Available at d13.documenta.de

“Bones of the Disappeared Get Lost again after Excavation,” bianet.org.

G.W. Leibniz, Monadology, ibid.

For him, whatever is the case is necessarily the best of all possible worlds anyway.

This applies particularly to the bones of murdered Kurdish individuals, which get extremely different treatment according to whether they were killed during the Anfal operations ordered by Saddam Hussein in Iraq, or by Turkish armed forces and militias during the civil war of the 1990s. The Anfal mass murders were investigated by world-class military specialists and interdisciplinary teams, whereas the Turkish cases were barely investigated at all.