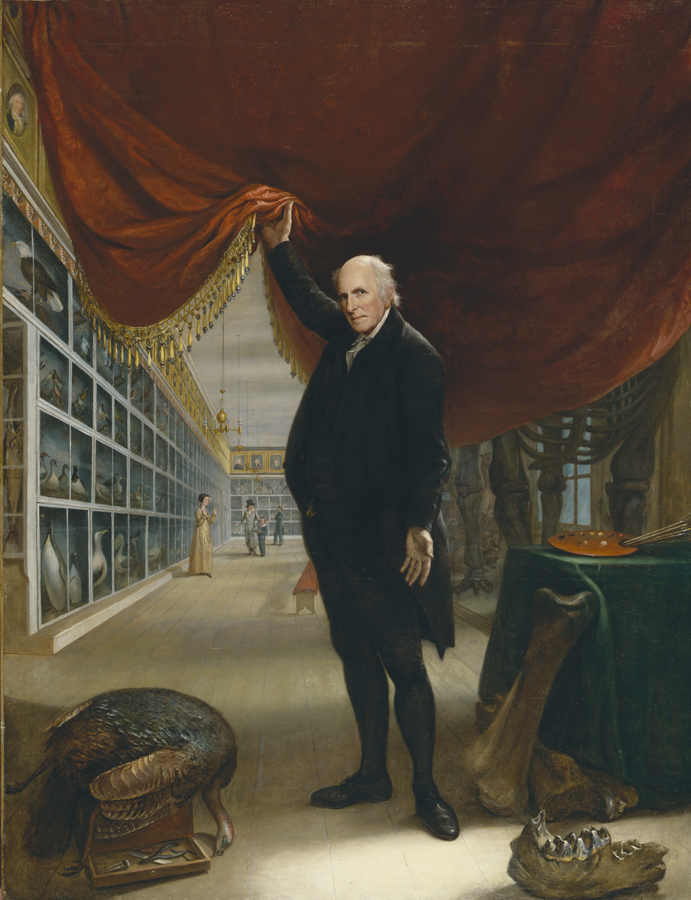

Quoted from Charles Coleman Sellers, Mr. Peale’s Museum. Charles Willson Peale and the First Popular Museum of Natural Science and Art (New York: Norton, 1980), 46. See also Charles Willson Peale, “To the Citizens of the United States of America,” in Museum Studies: An Anthology of Contexts, ed. Bettina Messias Carbonell (1792; Oxford and Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2004), 130. On biographical details, see also David C. Ward, Charles Willson Peale: Art and Selfhood in the Early Republic (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004).

Sellers, 159.

In Peale’s narrative painting The Exhumation of the Mastodon (1806–08), an artistic reenactment of his 1801 scientific excavation, numerous family members and friends appear, although with all certainty, they were not present. The painting hung for a long time in Peale’s Baltimore Museum (founded by Rembrandt Peale in 1814) and is currently part of the collections of the Maryland Historical Society.

Mieke Bal, “Telling Objects: A Narrative Perspective on Collecting,” in A Mieke Bal Reader (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), 170.

Joseph-Marie Degérando, The Observation of Savage Peoples, trans. F.C.T. Moore (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1969), 63. See also Tony Bennett, The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics (London and New York: Routledge, 1995), 194.

Alexander von Humboldt, Amerikanische Reise: 1799–1804, ed. Hanno Beck (Wiesbaden: Erdmann, 2009), 289–92.

Ward, Charles Willson Peale, 179–80.

Mieke Bal, “Telling, Showing, Showing Off,” in A Mieke Bal Reader (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2006), 204.

Georges Bataille, “Museum,” in Encyclopedia Acephalica: Comprising the Critical Dictionary and Related Texts, eds. Georges Bataille, Isabelle Waldberg, and Robert Lebel, trans. Iain White (London: Atlas Press, 1995), 64.

Ibid.

Ibid.

See Bennett, The Birth of the Museum, 76.

Tiffany Sutton, The Classification of Visual Art: A Philosophical Myth and Its History (New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 18–19.

Cesare Pavese, Dialogues with Leucò, trans. William Arrowsmith and D.S. Carne-Ross (Boston: Eridanos Press, 1989), 190.

Ibid., 196. In Quei loro incontri (2005), Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub filmed the dialogue.

ICOM Code of Ethics for Museums (Paris: International Council of Museums, 2006), 15.

Ibid., 9.

The Palestinian physician Tawfiq Canaan (1882–1964) collected and catalogued nearly 1,500 amulets and talismans until 1948. This collection has been at the Birzeit University in Ramallah since 1995; see href="http://virtualgallery.birzeit.edu">→. Canaan also put together a separate selection of 230 objects for Sir Henry Wellcome, who bequeathed them to the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford. Ettore Guatelli (1921–2000) was a collector of used objects from daily life. The Fondazione Museo Guatelli in Ozzano Taro near Parma has existed since 2003; see →.

A Mieke Bal Reader, 285.

The figures quoted are from various sources: Statistische Gesamterhebung an den Museen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland für das Jahr 2009 (Berlin: Institute for Museum Research, 2009), href="http://www.smb.museum/ifm/dokumente/materialien/mat64.pdf">→; Nora Wegner, “Besucherforschung und Evaluation in Museen,” in Das Kulturpublikum: Fragestellungen und Befunde der empirischen Forschung, eds. Patrick Glogner and Patrick S. Föhl (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2010); Julia Voss, “Mensch, was suchst du bei der Kunst?” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, September 20, 2007, 37.

Bericht zur Lage der Bibliotheken 2010 (Berlin: Deutscher Bibliotheksverband, 2010), 4.

Pierre Bourdieu and Alain Darbel, The Love of Art: European Art Museums and their Public, trans. Caroline Beattie and Nick Merriman (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2002), 37.

Translated from the German by Lisa Rosenblatt.