Tony Shaw, Hollywood’s Cold War (Edinburgh University Press, 2007), 26.

James Harvey, Romantic Comedy in Hollywood from Lubitsch to Sturges (Da Capo Press, 1998), 392. Tatjana Jukić observes that “Ninotchka remains dedicated to the revolution even after everybody else’s sense of politics has shifted and mutated, and even after she herself has abandoned her initial strict bureaucratic socialism.” “The October Garbo: Classical Hollywood and the Revolution,” Studia Litterarum 2, no. 2 (2017): 58.

This essay in intended to contribute to an understanding of Lubitsch as a political filmmaker, examining the relationship between comedy and politics in his work. Lubitsch’s great political trilogy, composed by Trouble in Paradise (1932), Ninotchka (1939), and To Be or Not To Be (1942), deals with the biggest shock to the capitalist system the world has yet known, the Great Depression, and the two major historical responses to the deadlocks of capitalism: communism and fascism.

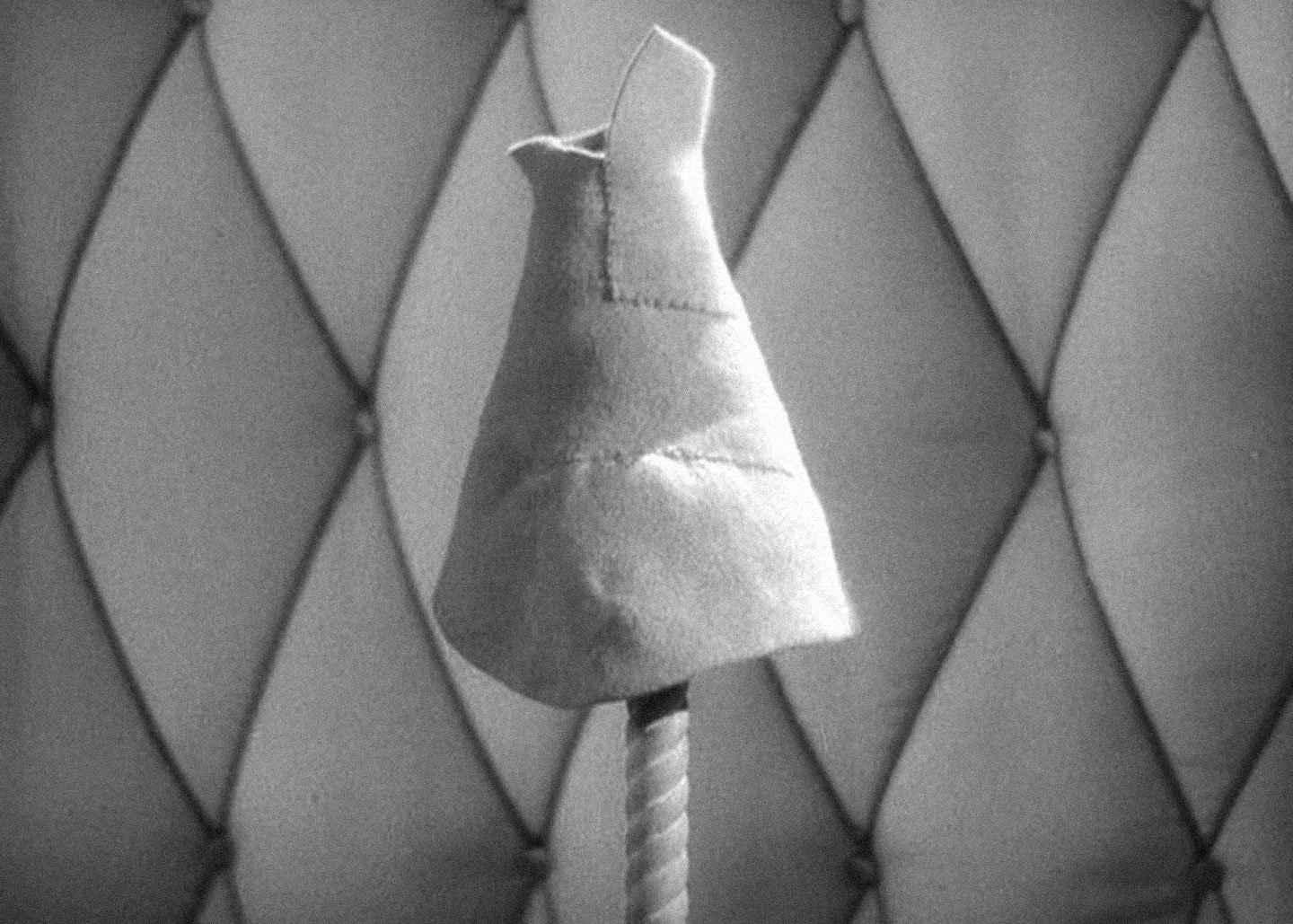

As Marjorie Hilton observes, Ninotchka’s new Western hat and dress are curiously reminiscent of Soviet avant-garde aesthetics: “Paradoxically, as much as this outfit is meant to convey Western fashion forwardness, it also evokes Russian constructivist experiments in fashion of the revolutionary years.” “Gender and Ideological Rivalry in Ninotchka and Circus: The Capitalist and Communist Make-over,” Studies in Russian and Soviet Cinema 8, no. 1 (2014): 13.

Lenin comments in his conversations with Clara Zetkin: “You must be aware of the famous theory that in Communist society the satisfaction of sexual desires, of love, will be as simple and unimportant as drinking a glass of water. This glass of water theory has made our young people mad, quite mad.” Clara Zetkin, Reminiscences of Lenin (1924; Modern Books, 1929), 57–58. Bolshevik feminist Alexandra Kollontai, to whom this theory is often wrongly attributed (including by Lenin himself), is rumored to have been the inspiration for the character of Ninotchka. An outspoken proponent of sexual liberation and the only female member of the Central Committee, she was also sent abroad and eventually became the Soviet Ambassador to Sweden, coincidentally Garbo’s homeland. In fact, however, Ninotchka was modeled not on Kollontai but Ingeborg von Wangenheim, wife of Lubitsch’s friend and actor Gustav von Wangenheim; the communist couple fled Nazi Germany to Russia in the early 1930s, and Lubitsch visited them during his trip to Moscow in 1936. For more on this connection, see Laura von Wangenheim, In den Fängen der Geschichte: Inge von Wangenheim Fotografien aus dem sowjetischen Exit 1933–1945 (Rotbuch Verlag, 2013), 12, 17–18.

Sigmund Freud, “The Question of Lay Analysis,” in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. 20, trans. James Strachey (Hogarth, 1955), 195.

Harvey writes: “According to some accounts, the whole project began with ‘Garbo laughs!’: once they had the slogan, they looked for a movie to go with it. It was Melchior Lengyel, a Hungarian playwright now on the MGM payroll, who came up with the idea of a Soviet in Paris succumbing to capitalist delight.” Romantic Comedy in Hollywood, 384.

For a discussion of another of these Lubitschean partial objects, see my analysis of the jeweled handbag in Trouble in Paradise: “Comedy in Times of Austerity,” in Lubitsch Can’t Wait: A Theoretical Examination, eds. Ivana Novak, Jela Krečič, and Mladen Dolar (Slovenian Cinematheque, 2014), 34–38.

Ivana Novak and Jela Krečič, “Introduction,” in Lubitsch Can’t Wait, 12; original emphasis. This passage is also discussed by Slavoj Žižek in Absolute Recoil: Towards a New Foundation of Dialectical Materialism (Verso, 2014), 293–94.

William Paul, Ernst Lubitsch’s American Comedy (Columbia University Press, 1983), 219.

For a contrary opinion, see Harvey: “He decides to tell her a joke. But this works no better, mainly because the joke is so dumb.” Romantic Comedy in Hollywood, 383.

See Alenka Zupančič, Why Psychoanalysis?: Three Interventions (Nordic Summer University Press, 2008), 42–43. For two of Žižek’s discussions of the “without milk” joke, see Less Than Nothing: Hegel and the Shadow of Dialectical Materialism (Verso, 2012), 765–68; and Incontinence of the Void: Economico-Philosophical Spandrels (MIT Press, 2017), 140.

A brilliant example of this is provided by the Russian avant-garde writer and slapstick metaphysician Daniil Kharms: “There was a redheaded man who had no eyes or ears. He didn’t have hair either, so he was called a redhead arbitrarily. He couldn’t talk because he had no mouth. He didn’t have a nose either. He didn’t even have arms or legs. He had no stomach, he had no back, no spine, and he didn’t have any insides at all. There was nothing! So, we don’t even know who we’re talking about. We’d better not talk about him any more.” Today I Wrote Nothing, trans. Matvei Yankelevich (Ardis, 2009), 45.

Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, vol. 1, trans. Ben Fowkes (Penguin, 1976), 342.

I draw on Jukić’s discussion of the symbolism of milk and blood in her excellent “Garbo Laughs: Revolution and Melancholia in Lubitsch’s Ninotchka,” in Lubitsch Can’t Wait, 86–87.

Hilton, “Gender and Ideological Rivalry,” 16.

This notion of the drive is a key aspect of Lubitsch’s comedy. From a formal perspective, one can compare Ninotchka’s communist drive with that of the title character of Cluny Brown, a working class woman who has a peculiar passion for plumbing. The telltale features of the Lubitschean drive are that it doesn’t obey social rules and cannot be assigned its proper place; it emerges in inappropriate contexts and awkward situations (e.g., plumbing in the middle of a formal birthday dinner, communism in the powder room), like a laugh that comes not when commanded but only at the “wrong” moment.

For more on the hommelette (which Lacan also refers to as the lamella), see The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XI: The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, ed. Jacques-Alain Miller, trans. Alan Sheridan (W. W. Norton, 1981), 197–98; and “Position of the Unconscious,” Écrits, trans. Bruce Fink (W. W. Norton, 2006), 717–18.

A different version of this essay was first published in Slovenian, “Komunistka Ninotchka,” in Lubitsch: Komedija brez olajšanja, ed. Ivana Novak (Analecta, 2019).