Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

June 25, 2021 – Review

Caline Aoun’s “Sedimentary Matters”

Rahel Aima

Summer, muggy and punishing. In another city we might rely on our bodies to index its various accumulations: sunlight, sweat, melanin. Here, we use our cars. Steering wheels and leather seats that scald palms and thighs and—I had forgotten until I found myself hurtling down the highway unable to see—windows that fog up with the contrast between the hot, soupy air outside and our blessedly air-conditioned interiors. Since moving back to Dubai from Brooklyn earlier this year, I’ve been thinking a lot about terroir. What would work that reflects these atmospheric conditions, the filmy dust and sticky heat, look and feel like?

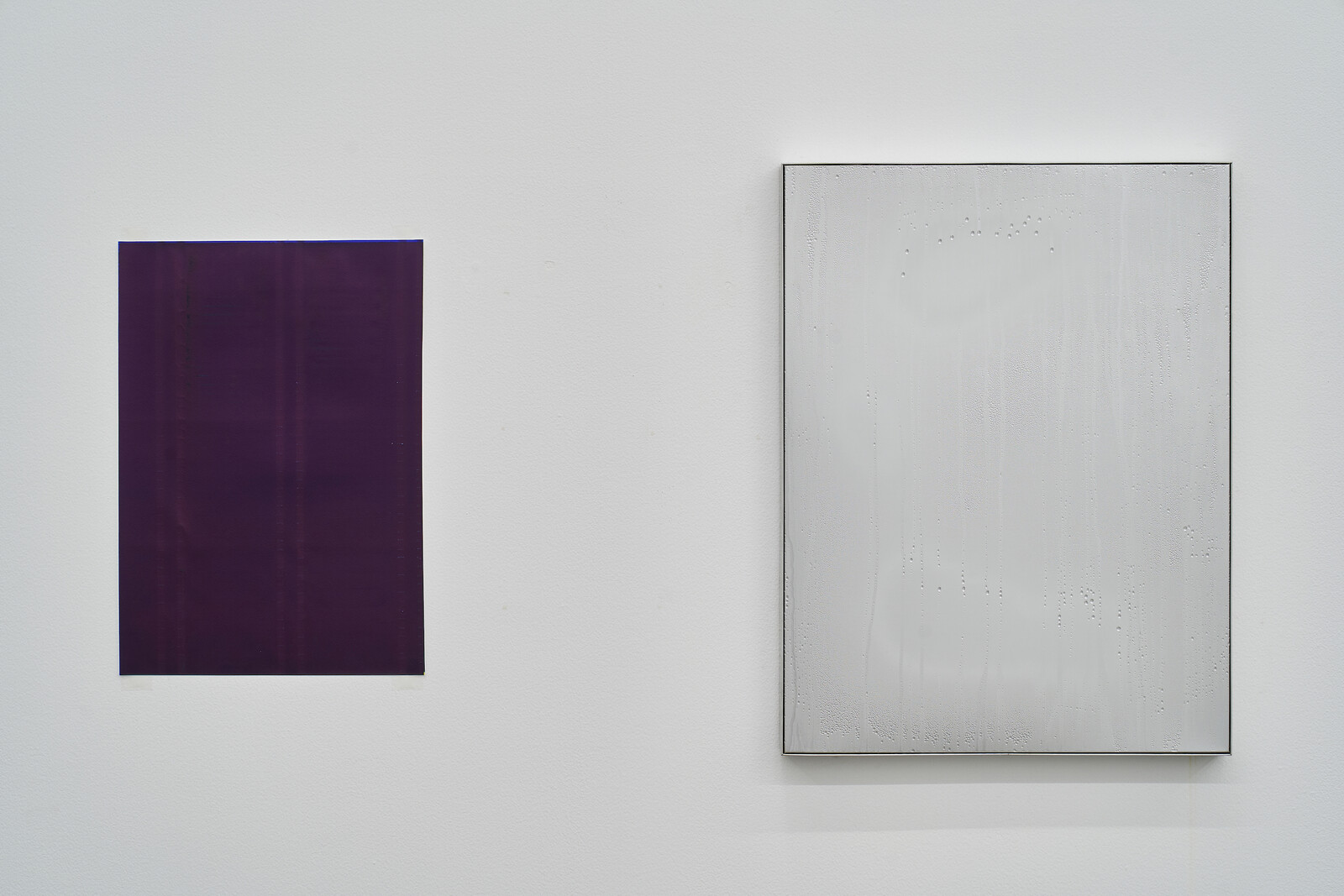

In Caline Aoun’s “Sedimentary Matters,” the uber-minimalist gallery is recast as an alluvial plain. There’s a rare sense of overflow and sensuous excess that overwhelms the space’s usual affective straitjacket. Things accrete into a material typology: ink, shadows, humidity, and the ghosts of all the other shows that have happened there. Upon entering the space, viewers encounter Condensations of the Invisible Space (all works 2021), a machine placed upon a high, spindly table with attached piping that goes through the wall. Those more mechanically literate might identify a fridge and compressor parts. On the other side is an …

April 15, 2021 – Review

Monika Grabuschnigg’s “Razed in Isolation”

Rahel Aima

We knew that the onslaught of pandemic art was coming. In Monika Grabuschnigg’s “Razed in Isolation,” it arrives by way of parable. Here, the cataclysmic disaster is the most powerful volcanic eruption ever recorded: Mount Tambora, Indonesia, 1815. Volcanic ash blocks the sun, changing the weather and affecting crops on the other side of the world. Things, as the Spice Girls once sang, would never be the same again.

At least, according to the exhibition text. This narrative plays out obliquely across a series of flat ceramic works, which are installed on the walls alongside aluminum panels and gnarly, gloopy tire rims. Loosely articulated nude figures cavort across glazed lavalike rocks, all overlapping limbs and orifices and doggy style. It later occurs to me that this kind of thing is probably a bit risqué here in Dubai. The skin tones on view resemble the shade range of a makeup counter up until a few years ago: alabaster, peaches-and-cream, golden, and—other. This is definitely the kind of cinematic event in which all the people of color die first.

The largest works suggest volcanic activity of a different kind, namely the plate tectonics of early geologic time. In works like Rite of passage …

March 5, 2021 – Review

Hiwa K’s “Do you remember what you are burning?”

Nadine Khalil

The second time I visit Hiwa K’s retrospective at Dubai’s Jameel Arts Centre it’s still daylight. In the outside sculpture park is the wood, cement, and metal sculpture One Room Apartment (2008-17), shown at Documenta 14 in Athens. A single staircase leads to a worn mattress on a morbid metal bed without walls. I climb it to take in the scene from above, and watch a bird land on the bedframe. Several kids are sprawled on a grassy patch, and in the distance is Palazzo Versace’s promise of decadence. In a city of labor camps and high-rises, Hiwa K’s comment on the rise of single-person living near minefields in Iraqi Kurdistan, the home he fled from and has recently returned to, takes on a different meaning. Where economic deprivation is fueled more by free-market economics than war, his work on atomized dwelling points to the divergent ways in which art manifests in different contexts: from the refugee crisis in Athens to the ongoing controversy over migrant workers’ conditions in Dubai.

Around the unsheltered bed, Hassan Khan’s multi-channel sound installation Composition for a Public Park (2013) expounds, fittingly, in three languages on the nature of bondage. Inside the exhibition, Hiwa K’s video …

October 24, 2019 – Review

Fazal Rizvi’s “How do we remember?”

Murtaza Vali

From Siegfried Kracauer to Roland Barthes, a photograph of a maternal figure in her youth has prompted some of the most important critical reflections on photography, and specifically its relationship to memory and death. For these authors, the photograph, despite its veracious claims, remains hopelessly inadequate, at odds with lived experience and unable to accommodate the emotional intensity of an intimate relationship. It requires, at least according to Kracauer, a supplement of oral history to even begin to access a person once known and lost. Prompted by a photograph of his maternal grandmother Jehanara Hasan, Fazal Rizvi’s “How do we remember?” is an investigation in this vein, complicated by Jehanara’s progressive dementia, which resulted in her having forgotten much of her life by the time the artist was old enough to remember her. It is an attempt to reconcile the dissonance between a photograph of youth, beauty, and vigor, around which memories and myths have coalesced, with the decay and deterioration of both the object itself but also the subject it portrays.

The exhibition opens with a pair of works that acknowledge how decay, mnemonic and material, troubles a photograph’s status as document. In She is beautiful on a piece …

June 20, 2019 – Review

Shilpa Gupta and Zarina’s “Altered Inheritances: Home is a Foreign Place”

Mahan Moalemi

The inaugural exhibition at the nonprofit Ishara Art Foundation—the newest addition to Dubai’s Alserkal Avenue, an art and culture hub housed in a former industrial compound—is built around an intergenerational dialogue between two Indian artists, Shilpa Gupta (b. 1976) and Zarina (b. 1937). Curated by artistic director Nada Raza, the show is a clear mission statement that sets the agenda for an artistic platform concerned with contemplating South Asia and the Gulf from a transnational perspective. Drawing on a wide array of each artist’s works, the exhibition allows for anecdotal as well as formal undercurrents to surface and resonate with each other.

Zarina’s “Home is a Foreign Place” (1999) is a double inauguration. Comprising a series of 36 woodcuts, the work sets the conceptual tone for the show and lends one of its motifs (Aasman [Sky]) to the foundation’s logo: a delicate, geometric pattern of rectangles, squares, and circles in perfect symmetry. In each of the woodcuts, processes of abstraction and translation feed into textual, visual, and numerical markers of how the artist relates her own life to ideas of home and belonging. Faasla [Distance] shows a straight line with “7438 miles” written above it—the distance between Aligarh in …

January 4, 2019 – Review

Joana Escoval’s “The word for world”

Jennifer Piejko

The Minimalism nurtured in SoHo and Marfa produced industrial cubes, steel beams, and gleaming planes until it was fortified and impenetrable, refracting metaphor or intimacy. Exposing rather than building up, its economical materiality favored the truly elemental, ruling out the human, or even the organic, as frill. So what to make, literally, of a substance like gold—an element weighed equal parts malleable and stable, mythical luxury, electrical conduit, and vitamin? The average human bloodstream contains a fraction of a milligrams of it; it is the treatment for both rheumatoid arthritis and dental cavities.

Joana Escoval’s fine, elegant gold wires embody Minimalism’s essentialism but not its burdens. She makes lines. This exhibition is an arrangement of soft, flat sculptures in pleasing shapes hanging on walls that share the movement’s austerity: the components of Escoval’s sculptures take up room in the way of Fred Sandback’s yarns delineate negative space, but refuse to occupy their volumes; they echo the gilded repetition of Walter de Maria’s Broken Kilometer (1979) while sidestepping its mass. Installed, her sculptures are aware of but don’t draw attention to each other, a whisper network over a choir ensemble. Lithe, skinny forms like An empty list of things missing (all works …

March 28, 2017 – Review

Sophia Al-Maria’s “EVERYTHING MUST GO”

Anna Wallace-Thompson

Qatari-American artist Sophia Al-Maria has long examined the architecture, urban planning, and customs of what she calls “Gulf Futurism,” including the phenomenon of mall culture. Her solo show in Dubai presents a new iteration of works exhibited last year at the Whitney Museum, New York, which further that investigation.

The room-sized installation The Litany (2016) features supermarket trolleys (some upright, some overturned) huddled around the main gallery’s central column like a rugby scrum comprised of brightly colored metallic potato chip packets, cheap mobile phones, and mini jello snack pots. The brands presented here are iconic for those who grew up in the Gulf. Labels such as Mr Krisp and Ali Baba evoke a kitsch nostalgic throwback to 1990s childhoods, and their jewel wrapper colors give the installation the appearance of a candy pile. This cluster is surrounded by a hundred or so digital prints of stills from the digital videos playing on the phones, with phrases including “Panic,” “Teargas Toner,” “Methane Gel,” and “Post-Truth Plumper” emblazoned on garish backgrounds.

A dark cavern, semi-hidden in the corner of the space, houses the 16-minute video Black Friday (2016). Filmed amidst expanses of gleaming marble in one of Doha’s yet-to-open mega malls, Black Friday is …

October 12, 2016 – Review

Hayv Kahraman’s “Audible Inaudible”

Melissa Gronlund

I passed a group of women wearing hijab on the beach the other day, talking in Arabic and English. They had pulled their chairs into the water and were sitting with the bottom of their skirts in the sea. “It’s hard for our sex to find happiness,” I heard one remark as I walked by. It was a comment so profound it almost felt scripted: this scene of women, draped in emblems of their gender, idly dropping historical truths.

Homosociality always makes the outsider covetous of insider knowledge. “What do women talk about,” I imagine men asking, “when we are not there?” Women alone together become not a group but a clique, a coven, a harem. In the Western imaginary of the Middle East, this assumption of difference is amplified by the Orientalization of Arabs, and the popular portrayal of Western–Middle Eastern relations as fundamentally adversarial. For US soldiers during the Iraq War, for example, curiosity about the other turned into paranoia and fear, when any Iraqi or group of Iraqi men could be a threat. In her current show at The Third Line, Hayv Kahraman explores these layers of cultural exclusion, desire, and apprehension, drawing a line between the representation …

February 22, 2012 – Review

"Domination, Hegemony, and the Panopticon"

Dina Ibrahim

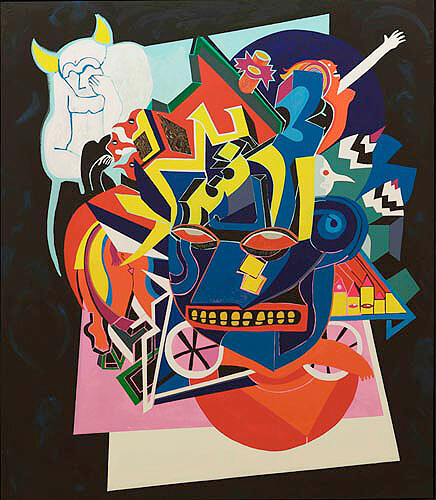

“Domination, Hegemony, and the Panopticon” is the fourth installment of “The State,” a series of exhibitions at Traffic, curated by the gallery-library-design studio’s founder Rami Farook. “The State” also includes a socio-historical journal and forum, a platform for dialogue and exchange about the state of the world today. The current exhibition, with works from nearly fifty artists, focuses on mechanisms of power as explored in the writings of Jean Baudrillard and Michel Foucault.

With a plethora of both international and Middle Eastern artists such as Jenny Holzer, Huda Lutfi, and Gilbert & George, the viewer is immediately made aware of a multitude of power struggles upon entering the space. The works are hung salon style, and that’s not the first challenge of contemporary art norms: there are no labels. Nothing indicates the artists’ names, nor the materials employed—thus key information used to link the works to a larger context of art history are denied us. This strong gesture of anonymity shifts any projection of knowledge (thus dominance, according to Foucault) from the works themselves to the viewer, who finds himself placed in the center of a Panopticon. Surrounded by the artworks like anonymous cell inmates, the viewer stands in the center …