“Domination, Hegemony, and the Panopticon” is the fourth installment of “The State,” a series of exhibitions at Traffic, curated by the gallery-library-design studio’s founder Rami Farook. “The State” also includes a socio-historical journal and forum, a platform for dialogue and exchange about the state of the world today. The current exhibition, with works from nearly fifty artists, focuses on mechanisms of power as explored in the writings of Jean Baudrillard and Michel Foucault.

With a plethora of both international and Middle Eastern artists such as Jenny Holzer, Huda Lutfi, and Gilbert & George, the viewer is immediately made aware of a multitude of power struggles upon entering the space. The works are hung salon style, and that’s not the first challenge of contemporary art norms: there are no labels. Nothing indicates the artists’ names, nor the materials employed—thus key information used to link the works to a larger context of art history are denied us. This strong gesture of anonymity shifts any projection of knowledge (thus dominance, according to Foucault) from the works themselves to the viewer, who finds himself placed in the center of a Panopticon. Surrounded by the artworks like anonymous cell inmates, the viewer stands in the center observing, examining, and judging (to hit on Foucault’s three principles of a disciplinary society).

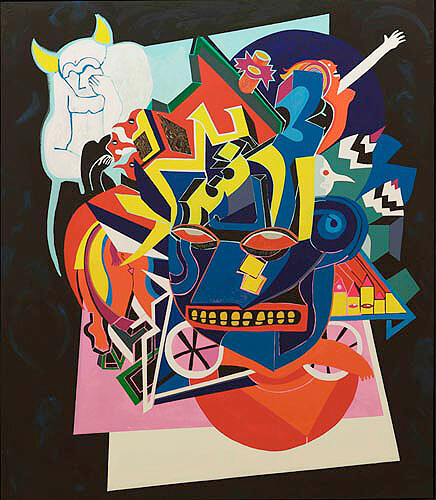

Upon entering the first room in the gallery space, one finds oneself on a battlefield of competing mediums, vying for the viewer’s attention. Small-scale, subtle photographs and prints are placed alongside large gestural paintings with eye-popping color like Athier Mousawi’s Mercedes Benz (2010) and Hesam Rahmanian’s You Fight So I Can Dance (III) (2010), with the latter embodying notions of power, quite figuratively. Progressing along, one’s attention is diverted to Rokni Haerizadeh’s Piss in Bed (2009), a large-scale painting of John Lennon and Yoko Ono in bed with a dead horse’s decapitated head at their feet—referencing the infamous Godfather movie scene. Through utilizing popular culture, the comical approach in this painting puts peace and love in bed with hatred and revenge.

The installation techniques utilized cause notions of knowledge and control to extend beyond the social and into the equivocal territory of art and exhibition space, triggering allusions of performativity. Upon entering the red and blue neon-lit second room in the gallery, power relations shift from the viewer being a spectator to that of active participant when confronted by three arcade machines (courtesy of Faile—a Brooklyn-based collaboration between Patrick McNeil and Patrick Miller). Again here, the viewer has been placed in a situation that goes against gallery conventions (ergo society’s regulations).

Indeed, a multitude of issues are addressed here through the focal point of power struggle, where conflicting parties vary. Some works, such as David Shrigley’s Don’t Play Here (1998), confront the tension between the authoritarian state and its subjects, while others, like Michele Giangrande’s Headless Chicken (2010), focus on the viewer’s existential struggle with himself. Other works find themselves at battle with a dichotomous relationship between art and the spectator; art and the art market; or the self and its alter ego as manifested in Arnaud Brihay’s two-part video installation, So Obvious (2012). Works such as Shahpour Pouyan’s The Hoof (2010) highlight religious power structures—with God being the ultimate Panopticon operator, while others exemplify political and even gender issues as illustrated by Huda Lutfi’s Egyptian Baroque (2006). Overall, the show tackles complex philosophical theory via pessimism, perhaps best elucidated by Damien Hirst’s hasty Skull Drawing (2008), which communicates, through a sense of urgency, cynical sentiments of a grim future.

While the theories of Foucault and Baudrillard may have been successfully communicated in the show via notions of authority and supremacy (albeit through art), one would question the relevance in the here and now. In response, it is important to recall here the one principle drawback to Foucault’s theory in particular: according to him, morality is created through the exercise of power. If one were to take this idea to its extreme, there would be no basis to claiming that anything is immoral. In a region like the U.A.E, where morality is manifest in laws of public decency, and art censorship is seminal (often taking precedence over such moral failings as money laundering and fraud), Foucault seems too relevant to not be questioned in this context of “the state” hegemony.

Surveillance and the all-seeing, all-knowing characteristics of technology seem to be the new instruments of modern discipline which have replaced pre-modern sovereigns (kings, judges). With the state controlling knowledge and the flow of information, it retains its authoritative status, and becomes, in this sense, the Panopticon prison guard, with its prisoners in isolation, left alone to critically examine the overflow of information and media channels, prompted by such instances as this exhibition.