November 11, 2016–March 12, 2017

At the 11th Shanghai Biennale, it isn’t possible to take a photograph without capturing people; the vast Power Station of Art—an electric plant turned kunsthalle since 2012—is busy throughout the preview day and public opening. The curators, Raqs Media Collective, have titled this edition of the biennale “Why Not Ask Again: Arguments, Counter-arguments, and Stories,” but the presence of swarming crowds prompts its own questions, the first of which is: who are these biennales for, and what does their audience want from them?

The previous edition, Anselm Franke’s “Social Factory,” was a biennale Shanghai deserved but did not necessarily want. The exhibition illustrated a particular danger in interrogating the social through frameworks structured by the debt of colonial modernity in a country that never had an internalized colonial experience. This isn’t to deny that the long shadow of troubled histories fall over the biennale: curators have always taken that into account, and a reminder for this edition came when, as the exhibition was being installed, a progressive bubble burst with the United States’ election of its next president. In times like this, what power can art hope to harness and generate?

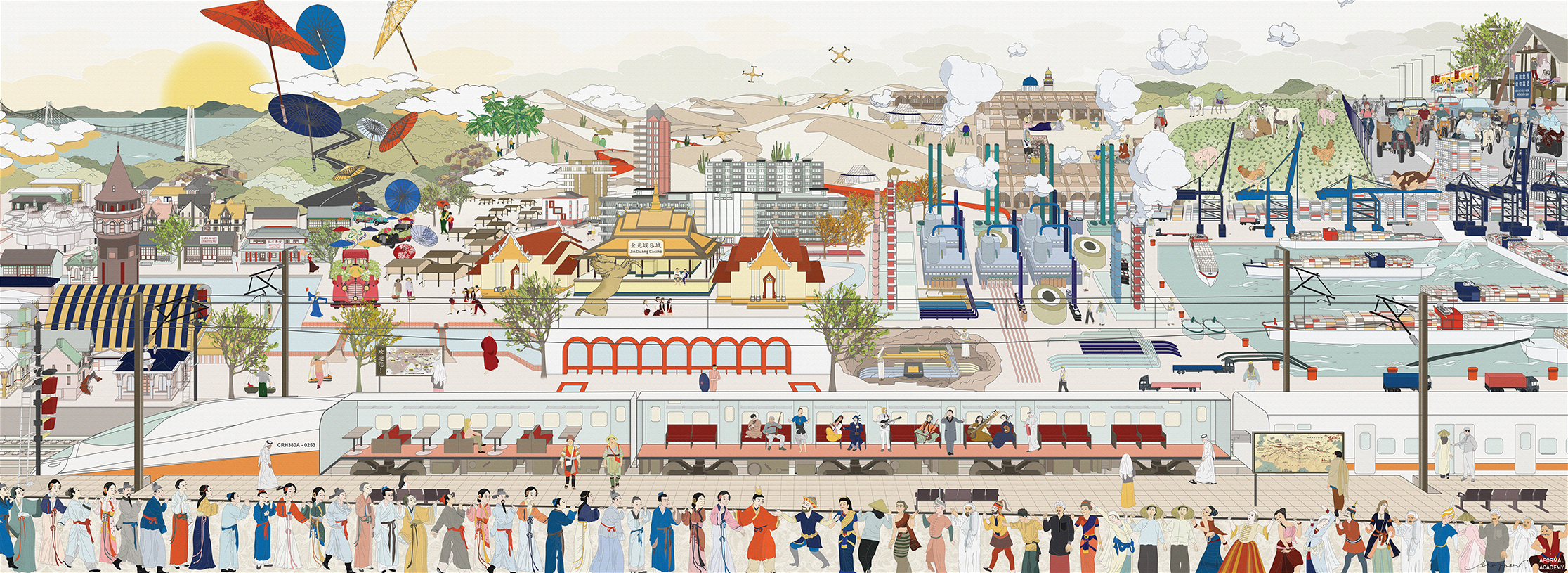

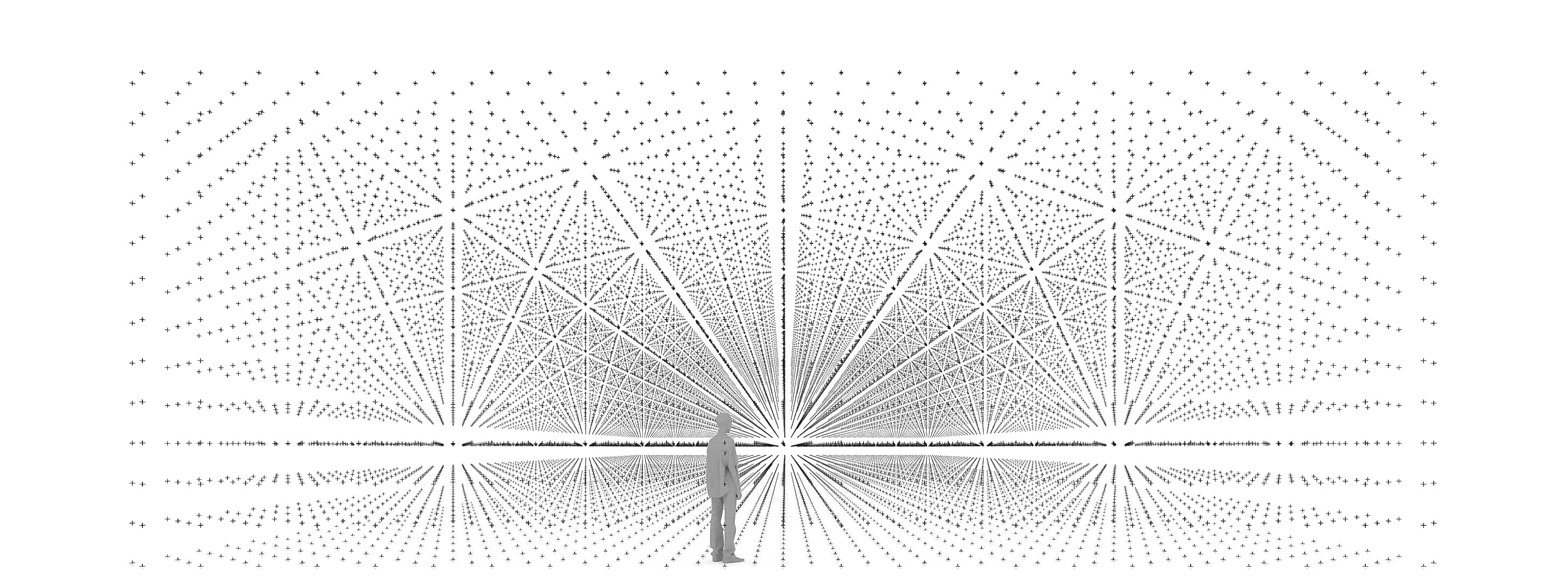

The Delhi-based trio Raqs Media Collective, comprising Jeebesh Bagchi, Monica Narula, and Shuddhabrata Sengupta, are pedagogues par excellence. Their artistic and curatorial practices perpetuate a core strategy of reckoning and, now, coping: to stay inquisitive yet “to look beyond answers.” So it is that speculative imagination and future-oriented utopianisms set the tone in the great hall, turning it into a planetarium of choreographed gestures and temporalities. At the center of the first floor, the dancers of Lee Mingwei’s Our Labyrinth (2015–ongoing) perform intermittent rituals of sweeping grains into patterns before gathering them back into a tight stack, each time imposing a unique, temporary magnetic field upon the space and its spectators; at Marjolijn Dijkman’s nearby Lunar Station (2015), a steel pendulum carves layering patterns on soft sand.

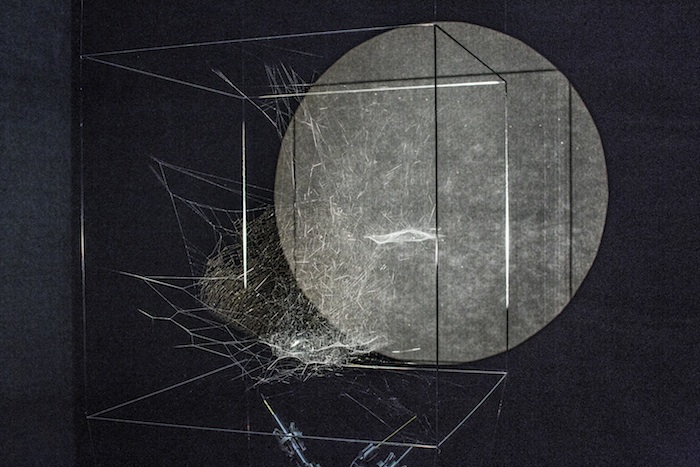

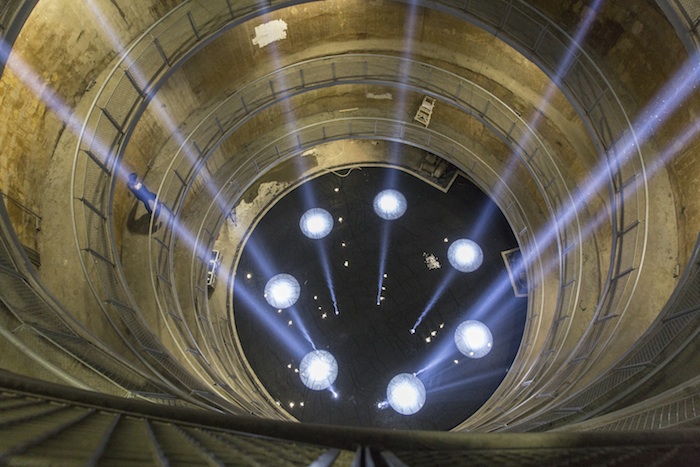

Forms and gestures are repeated and superimposed throughout the exhibition. The slow, long shots of assembly line workers with eerily fitting white masks in Yang Zhenzhong’s Disguise (2015) continue on various screens throughout the building, forcing the visitor to look again, and harder. Kendell Geers’s typographical interlacing of the Chinese characters for “revolution,” which form a glyph resembling the traditional pictogram of double happiness, magnifies an ironic and dissonant pleasure (PostPopRevolution, 2011). There’s also the architectonic sensation of tracing Liu Wei’s Panorama (2016)—a series of abstract structures that seem to constellate the ghosts of Vladimir Tatlin, Italian Futurism, and urban sculpture from 1990s China—up the grand stairs and towards the gargantuan installation built by Mou Sen and MSG, an experimental theater collective founded by Mou. Titled The Great Chain of Being—Planet Trilogy (2016), it is a “storytelling machine” about humanity’s dystopian turn: visitors enter through a crashed airplane broadcasting murky sound-bites of recent political regimes to explore the dark hearts of a strange (or estranged) planet of eschatological spectacles and post-human digital ruins. The theatrics are heavy-handed, with its crater, chasm, and a torchlight jerking menacingly above like the Eye of Sauron, but there’s some validity in the naturalism of this harrowing visualization, as dystopia manifests itself more and more readily in immediate realities.

It’s not hard to recognize parallels between Planet Trilogy and the “Three Body Trilogy” (2006–10), the widely celebrated series of sci-fi novels by Liu Cixin and a prime inspiration for Raqs Media Collective’s biennale. Liu’s story of intergalactic struggle also had its genesis in a recent humanitarian crisis—the political purges of the Cultural Revolution—before evolving to ask how humanity might grapple with technology and morality in a future that’s not necessarily anthropocentric. Cutting a path between cultural pessimism and techno-optimism, Raqs emphasizes the importance of embracing the unknown by mounting an ambitious and multidisciplinary exhibition, not unlike the anticipation of “radical uncertainty” advocated by economists like Mervyn King in late-stage capitalism. More importantly, the biennale pays homage to another important “Three Body” metaphor: when the Trisolaris civilization declared its impending destruction of lives on earth—having imposed a “lockdown” on the scientific progress attainable by humans and belittled mankind as “bugs”—one of the story’s human protagonists pointed out, to his devastated peers, that bugs are notoriously resilient and, when functioning collectively, a formidable force.

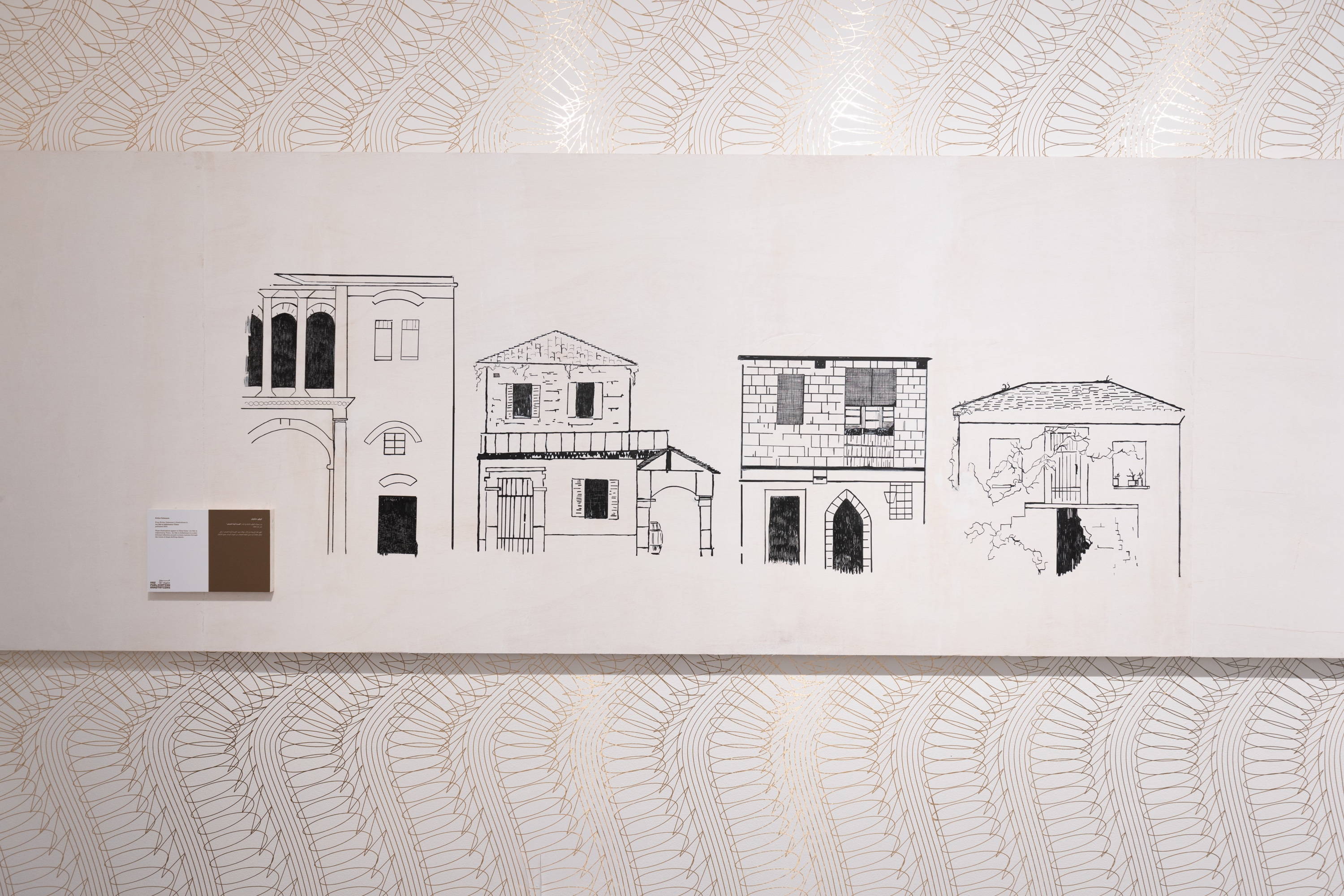

The biennale is among the most heavily populated I’ve seen, not only in the volume of visitors but also in the sheer amount of faces, figuration, lived experiences, live performances, personal stories, and fictions on display. This makes it relatively accessible for the art-curious, non-specialist public, and most works, in their varying tempos and modes of unfurling (and despite the usual translation issues) were able to sustain that curiosity. Hao Jingban’s analytical yet befuddled engagement (Off Takes, 2016) with salvaged, grainy footage of ballroom dancing at crucial points in modern Chinese history—the 1950s and 1970s—works like a spell. Lu Pingyuan’s horror stories (Story Series, 2013-ongoing) play on familiar art-world tropes, providing small doses of morbid comic relief. Visitors walk up to the folding screens on which Patty Chang’s Wandering Lake (2009) is projected, to become engrossed in her slow cleaning of a dead sperm whale. Jagdeep Raina’s drawings of Sikh communities in Canada (Reverberation Coils, 2015-2016) demand scrutiny by employing photographic methods of cropping and refocusing similar images, whereas Georges Adéagbo mounts evidence of a foreign yet rigorous processing of flea market memorabilia in Shanghai (“The Revolution and the revolutions”…!, 2016). There are the elusive caresses of ideological pasts in Desire Machine Collective’s Noise Life I (2014) and the haunting certainty of erased bodies in Khaled Barakeh’s images of refugees’ Pietà moments (The Untitled Images, 2014). With 92 artists participating in the main exhibition, and a special program titled “51 personae” which celebrates noteworthy local personalities, this exhibition manifests itself in a spectrum of poetry, humor, woes, and longing. It’s a very analog kind of interactive art, where interactivity isn’t defined by corny gadgetry but by engrossing one in another, in an other.

Raqs Media Collective’s biennale was keenly anticipated because their appointment represents a very Asian choice, neither Chinese nor Western, but one that activates the direct and refracted resonances in between. In the curatorial statement, they expressed hope of producing “a storm of desires in your heart.” Yet “Why Not Ask Again” finds its ultimate meaning in mobilizing compassion through curiosity. It’s a compassion channeled equally towards the stars and the bugs; the kind in which we might find both solace and solidarity.