“A repetitive moment becomes eternity.” This fragment of speech, ringing through Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in Philippe Parreno’s installation Anywhen (2016), might equally describe the frustration or elation of viewers’ experiences of moving image artworks. This season’s blockbuster exhibitions of film and video—Frieze Film (October 6–9, 2016), BFI London Film Festival’s Experimenta (October 6–16), and Parreno’s commission for Tate Modern (October 4–April 7, 2017)—showcased new works in these media through a variety of structures, some more effective than others.

When considered against the relative paucity of moving image works in the booths of Frieze Art Fair this year, the Frieze Film project—which commissioned work by Samson Kambalu, Rachel Maclean, Shana Moulton, and Ming Wong—seemed like an effort to redress the balance. The works were shown at scheduled times in the Frieze auditorium and also on national television as part of Channel 4’s Random Acts strand, which inserts three-minute shorts between programs. But to those already familiar with the oeuvres of the featured artists, this year’s commissions felt too brief; introductions to their style and ideas, rather than fully formed works.

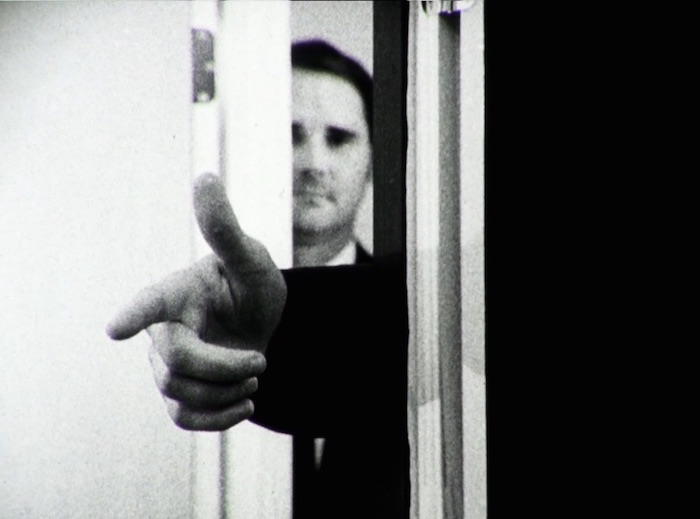

When it is installed in an exhibition space, as at the 2015 Venice Biennale and now at London’s Whitechapel Gallery (23 August, 2016–8 January, 2017), Samson Kambalu’s “Introduction to Nyau Cinema” has a powerful impact. The work surrounds viewers with playful silent films projected on every wall, connected by texts that evoke their inspirations. In the Nyau films—all of which last less than a minute, following a set of rules published in 2013—the artist often appears as a protagonist, evoking slapstick and early cinema tropes, as well as signifying rituals of film presentation in his native Malawi.

In the context of Frieze London, however, the presentation of four films from the series seemed not only safe but confusing. Aspect ratio aside—these four are in widescreen, whereas all of the others are 4:3—it’s unclear what distinguished these Nyau films from any others, or why they were grouped together. Furthermore, their exhibition on television and in the Frieze auditorium violated one of Kambalu’s Nyau Cinema rules: “Screening of a Nyau film must be in specially designed cinema booths or improvised cinema installations that complement the spirit of the films.”1

Of the four commissions, Rachel Maclean’s Again and Again and Again (2016) was the only work to take advantage of the project’s context and strict three-minute duration, creating an eye-catching music video that sped the viewer to the finish line. A chant of “we want data” morphs into a full-on techno-pop song, pushing Grimes-style vocals and visuals to a comic extreme. Data here is not just cellular; it’s also the data the government mines from our communications, the materials it requires for immigration, our digital footprint. Maclean’s video was not only the most absorbing of the group, but also the work that—despite engaging in fantasy and visual excess—offered the deepest insight into to our contemporary situation.

As Frieze Film is a sidebar to the fair, so Experimenta is the artist moving image strand of the BFI London Film Festival. This year’s most rewarding works shared a thread of animating historical details, bringing the past to the present through reenactment, extrapolation, or allegory. Deborah Stratman’s The Illinois Parables (2016) uses all these techniques to make an experimental catalog of radical people and astonishing events through the history of the midwestern American state. A devastating 1925 tornado, for example, is examined topologically through layers of news coverage and aerial film footage, while a soundtrack shifts and cycles through first-person testimony, a mournful gospel soul tune, emergency broadcast radio, and finally a blend of abstract noise and contemporary disaster scene audio. This slippage from the past into the present animates sequences like the recreation of the Chicago Police Department’s demonstration for the media of the murder scene of Fred Hampton, or a hot air balloon taking flight over Michael Heizer’s Effigy Tumuli (1985) at Buffalo Rock State Park.

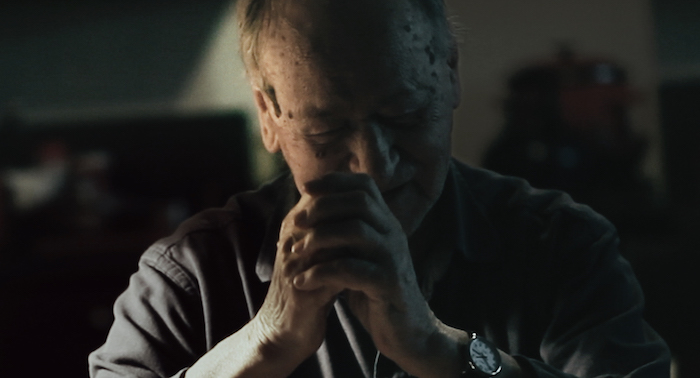

Douglas Gordon’s I Had Nowhere to Go (2016) is an adaptation of Jonas Mekas’s diaries from 1944–1954, the period which saw his flight from rural Lithuania, subsequent capture and internment in a Nazi forced labor camp, and his eventual emigration to Brooklyn. Gordon’s tumultuous film gives precedence to Mekas’s voice, which narrates a fractured sequence of these scenes. The vast majority of the film takes place with nothing on screen, a blank canvas training the audience’s attention on the soundtrack to a period of confusion, anger, and finally relief. “I had nowhere to go” is Mekas’s refrain in the shelter of New York City’s streets; a liberating, affirmative statement after years of hardship. Gordon arranges Mekas’s passages through an associative and poetic sequencing which mimics memory’s echo. This is reinforced by several sparse images: green trees swaying in a breeze, a chimpanzee lounging and gazing directly into the camera like a mirror of the viewer, or potatoes and onions roasting on a bed of embers. Gordon peels back the layers of Mekas’s testimony, not simply illustrating his journey but also illuminating the passage of time, the processes of remembering, and the collective experience of the audience.

If the best works from Experimenta reanimated history, Parreno’s Anywhen animates the bodies of its viewers. The work utilizes the cavernous space of Turbine Hall, augmenting its architecture with light panels, a large carpet on which visitors are invited to sprawl, and a massive projector and screen system which moves from the ceiling to the floor. Each of these systems interact in complex ways: flickering lights are triggered by sound, lighting elements move and cast shadows, fish-shaped balloons float freely around the space, bumping into walls or interrupting the projector beam. In this way, Anywhen is constantly shifting, a flowing ecosystem of energies that viewers orient themselves in relation to. Over several visits, which because of the always-changing configurations of the work result in different experiences of it, Anywhen gains an alluring strangeness, a persisting sense of unfamiliarity. When one realizes the whole installation is controlled by bio-reactive microorganisms, viewable inside a glass room in the far end of Turbine Hall, the character of the work becomes clearer. Music, video, and shifting sculptural forms lull audience members into positions of repose and contemplation not possible in Frieze Film and Experimenta.

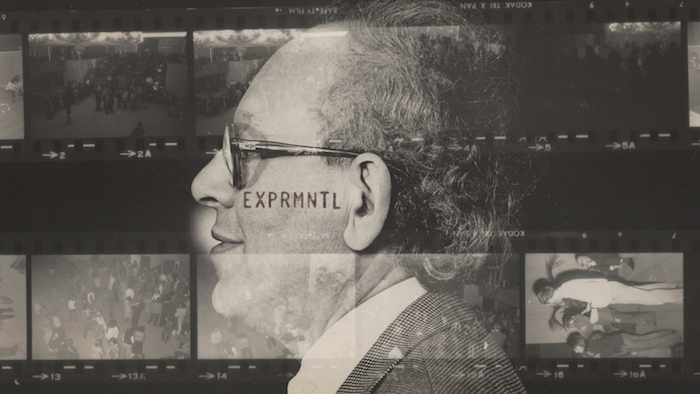

In the Experimenta-screened EXPRMNTL (2016), Brecht Debackere's documentary on the Belgian underground film festival held between 1949–1974, the French artist, theorist and curator Jean-Jacques Lebel describes the festival’s revolutionary spirit: “we expected unexpected things to happen.” This commitment to chance and unpredictability resulted in some of the most potent legends of experimental film history: Jonas Mekas surreptitiously screening Jack Smith’s censored Flaming Creatures (1963) to curious audiences in his hotel room; Lebel’s spontaneous, nude, and gender fluid “Miss Experimental” competition; the student faction led by Harun Farocki and Holger Meins protesting the imperialism of American filmmaking in the shadow of Vietnam.

Unfortunately, the mega-structures of Frieze Art Fair and the London Film Festival necessitate a carefully regimented schedule that can feel formulaic and staid. In the case of Frieze Film, this translated to small audiences and scant attention paid to the works; Experimenta suffered from the polite feature-length-screening-then-discussion format. By contrast, Anywhen allows the unexpected to take control, letting interactions unfold according to their own logic. Perhaps both Frieze Film and Experimenta could benefit from a dose of this exploratory spirit, creating a more deeply engaged audience experience through different venues, lower ticket prices, or experiments with new exhibition formats. Or perhaps they might turn to artists to consider new ways in which the structure of the institution could reflect the ambition and resistance to categorization of the best works they screen.

Samson Kambalu, “Nyau Cinema: The Rules,” published on the artist’s website Exercise and Exorcise (August 26, 2013). See: https://samsonkambalu.files.wordpress.com/2012/12/nyau-cinema-the-rules2.doc. Accessed November 8, 2016.