Protecting Cultural Heritage: An Imperative for Humanity, United Nations Brochure (22 September 2016), produced on the occasion of the “high-level meeting” at the United Nations, 10.

Vandalism on the world stage is nothing new, nor is its prosecution as a violation of international norms. A crucial precedent was set by the International Tribunal established in the aftermath of the Balkan wars, which tried and convicted criminals for “intentional cultural destruction.” But the Dayton Accords this Tribunal enforced pertained only to one conflict, conscribed in space and time. On this, see Andrew Herscher, Violence Taking Place (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010). In contrast, the International Criminal Court prosecuted Al Mahdi for his violation of a prohibition against “intentionally targeting cultural sites” that makes up Article 8 of the Rome Statute, an agreement that originates in a 1998 agreement to establish a permanent international judiciary.

Among those pushing for this bridging are journalists such as Robert Bevan, “Attacks on Culture to be Crimes against Humanity,” The Art Newspaper (27 September 2016) and scholars such as Stener Ekern, William Logan, Birgitte Sauge, and Amund Sinding-Larsen, “Human rights and World Heritage: preserving our common dignity through rights-based approaches to site management” International Journal Of Heritage Studies 18/3 (2012), 214-354. In Africa, the phrase “crime against world heritage” has been circulated; see Slimane Zeghidour, “Crime contre le patrimoine de l’humanité” in TV5 Monde (11 March 2015) →. In Western elite preservation circles, the two terms have also been cross-pollinated, as when Renzo Piano’s addition to a building by Le Corbusier was called a “crime against humanity.” Michael Z. Wise, “Confrontation at Art Museums,” ArtNews (29 October 2014). The film version of Bevan’s book The Destruction of Memory (dir. Tim Slade, 2014) features a number of international figures arguing for new “conjoining” heritage and humanitarian law. Most prominently UNESCO Secretary General Irina Bokova declares “You don’t choose between lives and monuments because it’s about identity.” On the differentiation between humanism and humanitarianism in the construction of international architectural heritage value, see Lucia Allais, “This criterion should preferably be used in conjunction with other criteria,” Grey Room 61 (Fall 2015): 92-101.

Rafael Lemkin, the author of the Genocide Convention, originally included “vandalism” in his definition of genocide but dropped this aspect when it threatened the passage of the convention. See A. Dirk Moses, “Raphael Lemkin, Culture, and the Concept of Genocide,” in Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies (Oxford: University Press, 2012).

International Criminal Court, Summary of the Judgment and Sentence in the case of The Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi (26 September 2016), 10.

This is a distinction reiterated in 1938 by Erwin Panofsky, “The History of Art as a Humanistic Discipline,” (1938) reprinted in Meaning in the Visual Arts (New York: Doubleday, 1955), 1–2.

The prevalence of video evidence was a factor in the court’s decision to take on the Al Mahdi case for cultural property crime alone, producing what Foreign policy calls “an evidentiary slam-dunk” →. But it was his confession that established the “gravity” of the crime and its punishment.

See Association Malienne des Droits Humains, “Mali: La comparution d’Abou Tourab au CPI est une victoire, mais les charges à son encontre doivent être élargies,” (30 September 2015). To argue for “widening” the charges they wield a combined language of heritage and humanity, see →. Erica Bussey of Amnesty International argued along similar lines in the Guardian →.

Faisal Devji, The Terrorist in Search of Humanity: Militant Islam and Global Politics (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008).

Hannah Arendt, “Karl Jaspers: Citizen of the World?” (1957) in Men in Dark Times (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1968).

Far from a tabula rasa, the landscapes of destruction that increasingly patched the globe after the first world war were shaped around architectural objects that had been designated for survival, singled out for reconstruction, or both. This history of monument survival is the subject of my forthcoming book, Designs of Destruction: Monument Survival and internationalism in the 20th Century.

Faisal Devji, “A Life on the Surface,” 21 September 2015, Hurst Publishing →.

Vyjayanthi Rao, “How to read a Bomb: Scenes from Bombay’s Black Friday,” in Public Culture 19, no. 3 (2007): 567-592, cited in Ibid., Devji (2008), 51.

Ibid., Devji (2015).

Like many other groups in the Sahel, Ansar Dine has shifting alliances within global terror networks. At the time of the destruction it was allied with Al Qaeda, but also also hosted recruiters and preachers coming through Timbuktu from a constellation of other groups. ISIS’s cultural targeting became systematic in Mosul in June 2014, when the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Shām issued a “Charter of the City” announcing that “all shrines and mausoleums” would be razed. Cited in Aaron Zelin, “The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria Has a Consumer Protection Office” The Atlantic (13 June 2014).

In “Between Cult and Culture: Bamiyan, Islamic Iconoclasm, and the Museum Author(s) The Art Bulletin, 84/ No. 4 (Dec., 2002), pp. 641–659, Finbar Barry Flood already critiqued the essentialist view of Muslim iconoclasm as a cultural pathology by inscribing the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddahs within tropes of global modernity, especially as a response to the “hypocrisy of Western institutions.” I wish to thank Byron Hamman for reminding me of this seminal article and for thoughtful comments on a draft of my own text as well.

Ansar Dine’s monitoring and patrolling of the sites was one reason for the UN’s decision to place them on the list of endangered cultural property. United Nations Press release, “Mali site added to List of World Heritage in Danger – UNESCO,” 13 July 2012 →. The ICC also noted that the destruction was a response to the initiatives of the Malian ministry of culture begun in 2013.

“Les Islamistes détruisent les derniers mausolées de Tombouctou” L’express with AFP (23 December 2012) →.

“Les Islamistes poursuivent la destruction des monuments de Tombouctou,” L’express with AFP (1 July 2012). These citations were made to Agence-France-Presse over the phone, reported widely (see for instance “A Tombouctou, les islamistes détruisent les mausolées musulmans,” Le Monde with AFP (30 June 2012) →. This citation is from the ICC’s own “unofficial internal translation” for the video MLI-OTP-0034-0395: “Our reference is not to international law, nor the United Nations, nor UNESCO … These international bodies … don’t concern us, and for us their indignation is an atonement … What is the value of these walls?” See also an interview of Sanda Ould Boumama by Marie-Pierre Olphand of RFI, “Mali: la destruction des mausolées de Tombouctou par Ansar Dine sème la consternation,” (10 November 2013), which became evidence MLI-OTP-0007-0228, and MLI-OTP-0020-0584.

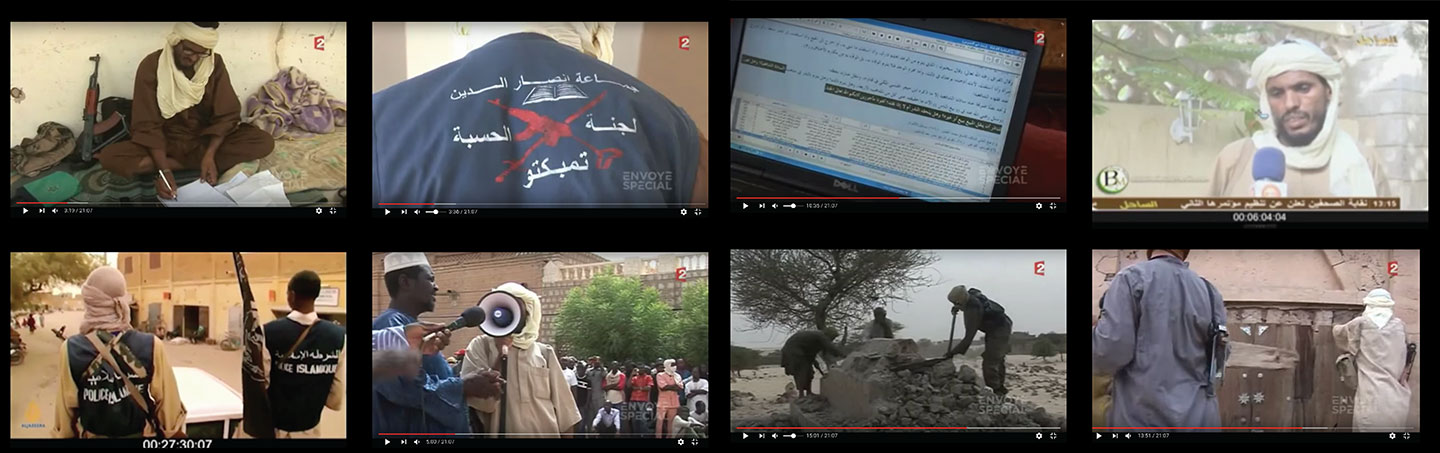

These videos, which serve as the core evidence in the ICC’s case against Al Mahdi, were shown in an elaborate multimedia presentation during trial. Originally they were recorded by a Mauriantian videographer, Ethnam Ag Mohamed Ethman who was embedded with Ansar Dine for months. Ethman periodically broadcast them on Saharamedia (for example, for June 20, 2012). Eventually they were acquired by producers and reporters from France 2, and broadcast in Envoyé Spécial on January 31, 2013 as part of the report Mali: La vie sous le régime islamiste” →. Henceforth Envoyé Spécial.

The Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi, Transcript, Trial Chamber VIII, 24 August 2016: ICC-01/12-01/15/T-6-ENG, 11. Transcript from ICC trial indictment (12 January 2015).

The ICC documents describes this as a rule against building anything measuring over “an inch” while press reports say “building anything that is taller than the span of a hand.”

Envoyé Spécial 15:07—15:30. "Settling the graves" is taswiyat al qoboor. Translation from original Arabic by Leen Katrib

“If a tomb is higher than the others, it must be leveled (…) we are going to rid the landscape of anything that is out of place” Cited in “The prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi,” Public Judgment and Sentence, 27 September 2016, (ICC-01/12-01/15), 20–21. “Un homme remercie Dieu après avoir détruit un tombeau plus protubérant que les autres; un autre qui loue Allah de leur avoir accordé toutes ses victoires et de leur avoir permis d’appliquer Sa Loi sur terre.” “Sahara média accompagne Ançar Edine en train de démolir les mausolées de Tombouctou,” Saharamedia (30 June 2012) →.

See note 19.

Envoyé Spécial 14:00—14:30. Translation from original Arabic by Leen Katrib.

“The door was condemned and bricked up. Over time, a myth took hold, claiming that the Day of Resurrection would begin if the door were opened. We fear that these myths will invade the beliefs of people and the ignorant who, because of their ignorance and their distance from religion, will think that this is the truth. So we decided to open it.” Cited in Trial Chamber VII, Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi, Public Judgement and Sentence, (ICC-01/12-01/15-171), 22.

In response to the question, “have you changed your religious conviction?”, Al Mahdi replies: “If you review my former statements, you will see that I was not convinced originally with the appropriateness to undertake such actions from the beginning because the decisions I had made were made on the basis of a legal decision. I said that what I did was based on a theory according to which one cannot build anything on tombs, and a tomb, according to the religious beliefs, should not be over 1 inch above the ground, and those mausoleums are far higher than that. (…) But from a legal and political viewpoint one should not undertake actions that will cause damage that is higher or more severe than the usefulness of the action. Such mausoleums I believe are not as harmful as the contradiction they represent as they are built on tombs, but the people who controlled the country at the time considered that such. (…) Thus, I believe that by doing that I do not change my beliefs, I should not undertake action that will cause damage to others. This is a former belief and a present belief of mine, sir.” Trial Chamber VIII, Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi, Transcript, 23 August 2016 (ICC-01/12-01/15-T-4-Red-ENG), 13.

“We are not here to decide on the fate of the author of single act of vandalism, but to render justice to memory and affirm the importance of symbol in the existence of a people.” Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi, Transcript, 24 August 2016. “His role as media spokesperson in justifying the attack” is from Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi, Public Judgement and Sentence, 27 September 2016, 39-42.

This choice of tools was also noted by the press. See →.

The English translation and transcription is Prosecution v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi, Transcript, 23 August 2016 (ICC-01/12-01/15-T-4-Red-ENG), 8–9. The French is ICC-01/12-01/15-T-4-Red-FRA. This and following quotations of Al Mahdi’s statement are re-translated by Leen Katrib from the Arabic video, not transcribed but made available by the court as “In the Courtroom Programme.”

Also critical to Al Mahdi’s performance as an international witness was the somewhat belabored procedure of his choosing a language for the trial. Being asked which language he preferred, al Mahdi chose Arabic, indicating his exo-graphic affinity is with global Islam rather than, the State of Mali whose official language is French. When he indicated this choice through his lawyer, however, the presiding judge replied that he should have spoken this choice himself. Once al Mahdi obliged, the judge then ensured an Arabic simultaneous translator, and asked all parties not speaking Arabic to pause periodically to allow this interpreter to keep up with proceedings.

“This is how deep the connection is between the mausoleums and the people of Timbuktu … to erase an element of collective identity.” Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi, Transcript, 22 August 2016, 21.

Ibid.

“He acted with the requisite degree of knowledge. He knew that the buildings targeted were dedicated to religion and had a historic character and did not constitute military objective” Trial Chamber VIII, Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi, Confirmation of Charges Hearing, 24 March 2015, (CR2016_02424), 25.

Jukka Jokilehto, “Human rights and cultural heritage,” International Journal of Heritage Studies 18, no. 3 (May 2012): 226–230.

Accordingly, Bensouda cited an elderly man captured on camera, declaiming the loss of the city’s “soul.” Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi, Transcript, 22 August 2016, (CR2016_05767), 19.

“These monuments, your Honours, were living testimony to Timbuktu's glorious past … a unique testament to the city's urban settlements. But above all they were the embodiment of Malian history, captured in tangible form from an era long gone yet still very much vivid in the memory and pride of the people who so dearly cherished them.” Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi Trial Hearing Transcript, 22 August 2016, (CR2016_05767), 17

Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi Transcript, 22 August 2016 (“CR2-16_05757”), 24.

The prosecution argued that the “multiple victims” aggravated the crime, while the chamber countered that it had “already taken into account the far-reaching nature of the crime.” “World Heritage” status means that the crime “not only affects the direct victims of the crimes (namely, the faithful and inhabitants of Timbuktu) but also people throughout Mali and the international community.” Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi Transcript 24 August 2016 (“CR2-16_05730”).

Mauro Bertagnin et Ali Ould Sidi, Manuel pour la Conservation de Tombouctou (Paris: Unesco, 2014).

See “Analyse et constat: Dégradation des bâtiments” and “Les matériaux de la tradition et le rôle des maçons” in Manuel pour la Conservation, pp. 61-70. See also Ali Ould Sidi, “Monuments and traditional know-how: the example of mosques in Timbuktu”, Museum International 58, 1-2, 229-230; “Timbuktu: Mosques face Climate Challenges” World Heritage Review 42 (2006), 12-17, and “Partnership to preserve Timbuktu”, World Heritage Review 29 (2009), 16-17.

Ibid., Manuel pour la Conservation, 61.

For Bensouda, rebuilding and regular architectural maintenance, in an allegory for peacemaking itself, “contributing to the workshop of peaceful coexistence.” Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi Transcript, 22 August 2016, 24.

I take inspiration here from Brian Larkin’s description of the mediality of the loudspeaker in Jos, Nigeria, a city where both daily life and conflict are, as in Timbuktu, mediated through techniques and technologies for attention and inattention. Brian Larkin, “Techniques of Inattention: the Mediality of Loudspeakers in Nigeria,” in Anthropological Quarterly 87(4), 989-1016.

Pietro M. Apollonj Ghetti, Étude sur les mausolées de Tombouctou (Paris: Unesco, 2013).

Robert Caillié, Voyage à Tombouctou, (1830) Facsimile (Paris: La Découverte, 1996).

Francesco Bandarin’s testimony at the ICC notably weaves together three themes of Timbuktu’s architecture to argue for its multivalent historical value: a site of material know-how, of religious aura, and an urban network that is a “focus point for religious life, the region… and focus for pilgrimage” Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi Transcript, 23 August 2016, 44.

Even Timbuktu’s famous manuscripts, which had been meticulously digitized before 2010, have been re-released into networks of global mobility. Originally housed in new museums on site, they were smuggled to Bamako before Al Mahdi’s group was able to get to them, thanks to a network of globally-trained curators, funded in part by a Ford Foundation grant. These funds had originally been granted in a “multidimensional and integrated United Nations initiative for stabilization” (MIUNIS) to Abdel Kader Haidara, a collector and librarian in Timbuktu, to conserve these manuscripts on site. They were officially diverted to help for the secret removal of these objects to Bamako by boat and car. “Trois Bibliothèques de manuscripts anciens réhabilitées à Tombouctou,” UN Press Release (1 December 2015) →.

On this history see Mary Jo Arnoldi, “Cultural Patrimony and Heritage Management in Mali” in Africa Today 61/1, (Fall 2014), pp. 47-67

On Timbuktu as a warscape see Fiona McLaughlin, “Linguistic warscapes of northern Mali,” in Linguistic Landscapes 1:3 (2015), 213-242.

On the use of these rituals in post-war reconciliation in both Timbuktu and Gao see Thierry Joffroy and Ali Ould Sidi, “Stratégie de reconstruction du Patrimoine Culturel détruit ou endommagé des regions du nord du Mali,” in Mali, post-crise: de nouvelles perpsectives pour le patrimoine (Paris: Riveneuve, 2015), 337-350. “Noble Pile” is from a description of one of the towers of the Djingareiber mosque by Heinrich Barth, Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa 1849-1845 a Vol, III. (London: Frank Cass & Co, 1965), 323.

Daniel Monk and Jacob Mundy have described the post-conflict environment as an ideological construct, a “reification” that helps to realize the interventionist habitus of the liberal international community. Daniel B. Monk and Jacob Mundy, “Conclusion,” in The Post-Conflict Environment (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press,2014), 219. While theirs is a critique primarily of statebuilding practices, it applies equally to softer cultural forms of post-conflict pacification such as the ones operated in Timbuktu, where urban heritage is reified along with the humanity that is produced in its defense.

Bensouda argued during the trial that “attacks on religious property are usually the precursors to the worse outrages against population” and therefore cultural punishment was “an integral part of humanitarian efforts.” Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi Transcript, 22 August 2016, 21. She is a vocal proponent of the use of the ICC to prosecute “sexual violence in conflict.” Esther Addley, “Fatou Bensouda, the woman who hunts tyrants,” The Guardian (5 June 2016) →. The idea of cultural violence “signaling” the presence of other human rights violations, and of the ICC trial “signaling” international policing in return, is articulated by Patty Gerstenblith and Bonnie Burnham in The Destruction of Memory. Raphael Lemkin himself wrote in 1923 that “physical and biological genocide are always preceded by attacks on cultural symbols.” Moses, Op Cit, 41.

See Laura Kurgan’s ongoing work to “document and narrate” the urban damage in the Syrian city of Aleppo, Conflict Urbanism →, and Eyal Weizman’s group’s work, collected in Forensis: The Architecture of Public Truth (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2014).

Superhumanity, a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, is produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.