Naomi Davidson, Only Muslim (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2012); Marcel Maussen, “The Governance of Islam in France: Church-State Traditions and Colonial Legacies” in Religious Newcomers and the Nation State: Political Culture and Organized Religion in France and the Netherlands, eds. Erik Sengers and Thijl Sunier (Delft: Eburon Academic Publishers, 2010), 131–154.

Gilles Kepel, Les banlieues de l’islam; Naissance d’une religion en France {The Suburbs of Islam: Birth of a Religion in France} (Editions du Seuil, 1987).

Historian Michel Renard examines the motivations for the pursuit of such a project, noting that, in addition to philanthropic and political motivations—and against the backdrop of the colonial pacification of Algeria—there were “also religious ones because Muslims are considered closer to Roman Christianity than are the Jews.” Michel Renard “Les prémisses d’une présence musulmane et sa perception en France — Séjours musulmans et rencontres avec l’islam” (Arkoun, 2006), 573–582.

Gerbert Rambaud, La France et l'islam au fil de l'histoire: Quinze siècles de relations tumultueuses (Monaco: Le Rocher, 2017), 321.

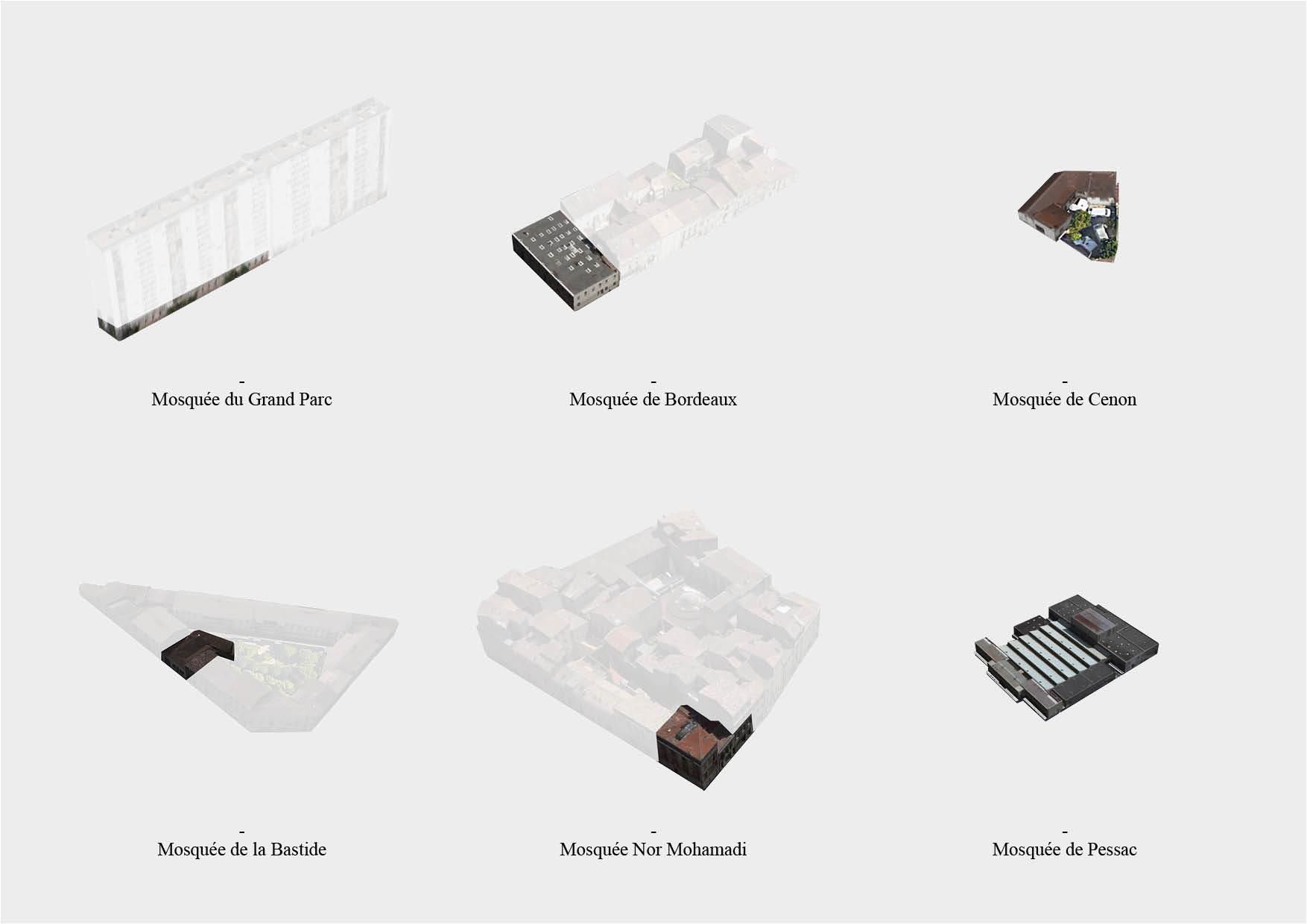

Elsa Provenzano, “Bordeaux: Une mosquée veut un abri extérieur pour faire face à l’afflux de fidèles, la ville refuse,” 20 Minutes, January 30, 2023.

Fanny Ohier, “Pleine à craquer aux heures de prière, la mosquée de Cenon s’agrandit,” France Bleue, May 14, 2019.

Former Mayor Alain Juppé declared to Sud-Ouest: “we made the decision to move the mosque project to the Garonne Eiffel, to a site where there are no residents and where parking spaces will be available. So there won't be any problem.” See ➝.

“The construction of a twelve thousand metre square mosque remains an extremely sensitive issue for elected officials… If, from the outset, he was in favor of the Grand Mosque project in Bordeaux, carried by a Tareq Oubrou to whom he is close and whom he considers to represent a moderate Islam, Juppé no longer wishes to speak on the subject.” See ➝.