The saga of the establishment and subsequent decline of the Children’s Health Resort was first unveiled to the local public in the exhibition project (Dis)Trust the Storyteller: The Case of Krvavica curated by the association Slobodne veze (Loose Associations) at Salon Galić in Split in 2021.

In the inaugural publication on the Children’s Health Resort in Oris magazine, back in 2008, architect and researcher Miranda Veljačić reflected on the poignant remnants left behind. She observes the devastated pieces of furniture, the beach equipment, and the canoes, all of which speak of the luxury that belonged to the youngest and the ill. This evocative statement underscores the stark contrast between the past opulence of the resort and its current state of neglect. In her assessment, the resort stands as a testament to an era when societal empathy and architectural innovation were seamlessly intertwined. Miranda Veljačić, “Perja na buri / Feathers in the Bora,” Oris 50, 2008. See ➝.

According to architecture historian Tamara Bjažić Klarin from the Institute for Art History in Zagreb, as presented in her lecture titled “Parallel Track of the Architect Rikard Marasović: A Sketch For Biography And Further Exploration,” which took place in Pula in 2023.

Igor Skopin, "In Memoriam Rikard Marasović (1913-1987),” Čovjek i Prostor 34 (1987): 5.

The complex was, for example, included in MoMA’s 2018 exhibition Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980.

This experience engaged the local and professional community and formed part of the international project “City-Hospital,” spearheaded by associations f.act from Graz, Intermundia from Zagreb, and mART from Makarska, and sought to prompt reflections on the intersection of illness, spatial environments, and healing practices. The communal cleaning action, as part of the program, was documented by filmmaker Matija Kralj Štefanić in a video To Cure a Place of Care - Liječenje lječilišta / Krvavica (2021), which can be seen here ➝.

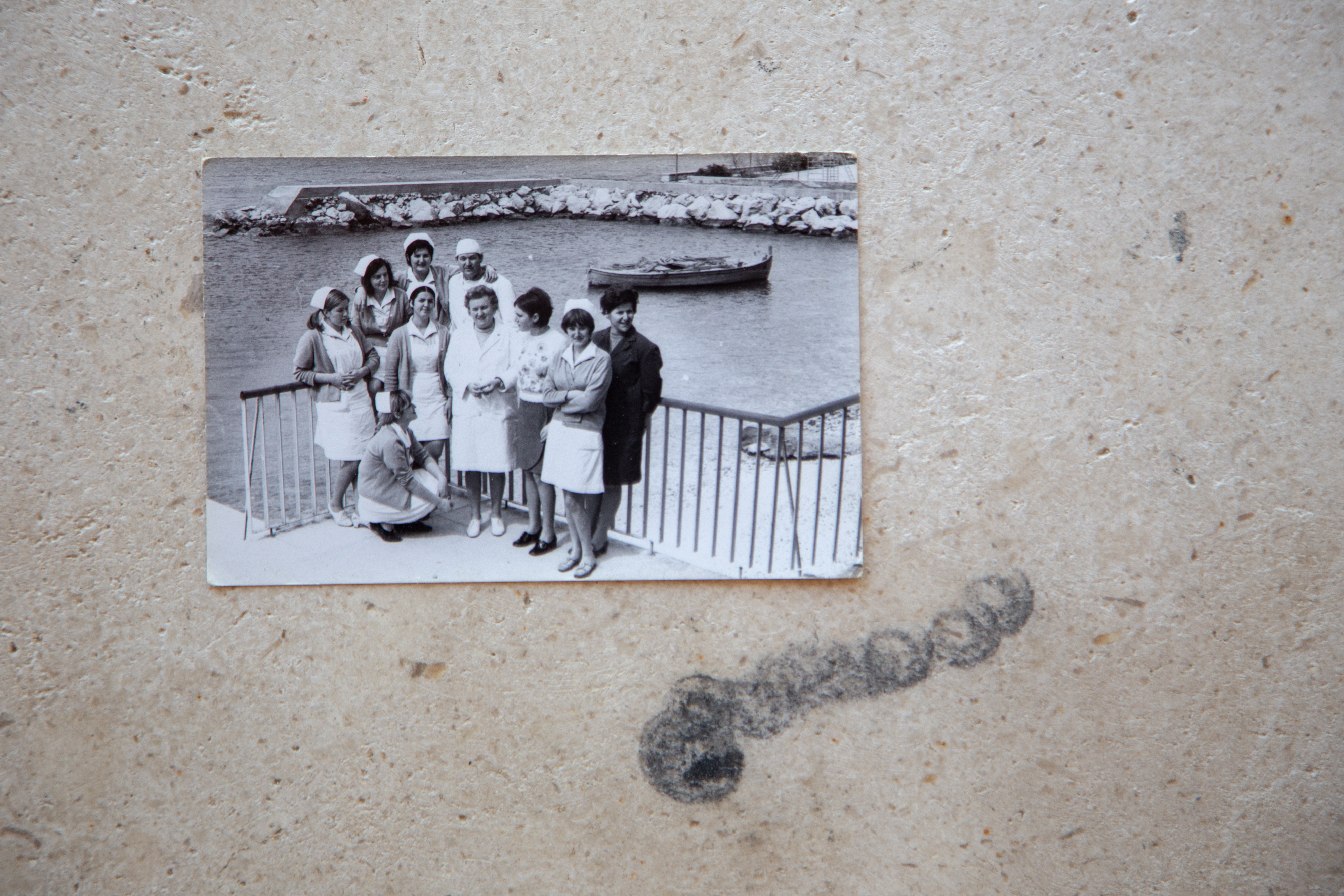

The film features interviews with architecture professionals such as Miranda Veljačić, an architect and researcher from Split, Stevan Rodić, an architect and urbanist from Novi Sad, and Rajko Jurišić, a local historian from Baška Voda. Former employees, such as Ineska Paić, a former receptionist from Makarska, and Josipa Balajić, an art historian and pedagogue from Krvavica, offer insights into the building's history and significance. Local actor Lovrenco Laušić brings Marasović's character to life, while Bojan Divić provides a compelling voice-over narration, further enriching the film's narrative collage.

More information about the program can be found here ➝.

Under the auspices of LINA and DAI-SAI, this has led to the creation of a zine, short films, texts, documentation, research, talks, and performances. Supported by the editorial construct Adria, the fanzine gathers thinking and contemporary cultural notes, as well as archival snippets, in hopes of weaving together something akin to an experience of a nostalgic road trip along the coastal highway, while remaining acutely aware of the rapidly accumulating crisis around us. Adria, S’lim 7 (July 2022), ➝.

“The Mysterious Object in the Pine Forest” is the name of an episode in the renowned documentary series Slumbering Concrete, which explores the modern architecture of the former Yugoslavia, its utopian aspirations and its disputed future, produced by the Hulahop production company for Croatian Radiotelevision in 2016.