Roland Barthes, “Inaugural Lecture at the Collège de France,” in The Continental Philosophy Reader, eds. Richard Kearney and Maria Painwater (New York: Routledge, 1996), 365–366.

Ibid., 366.

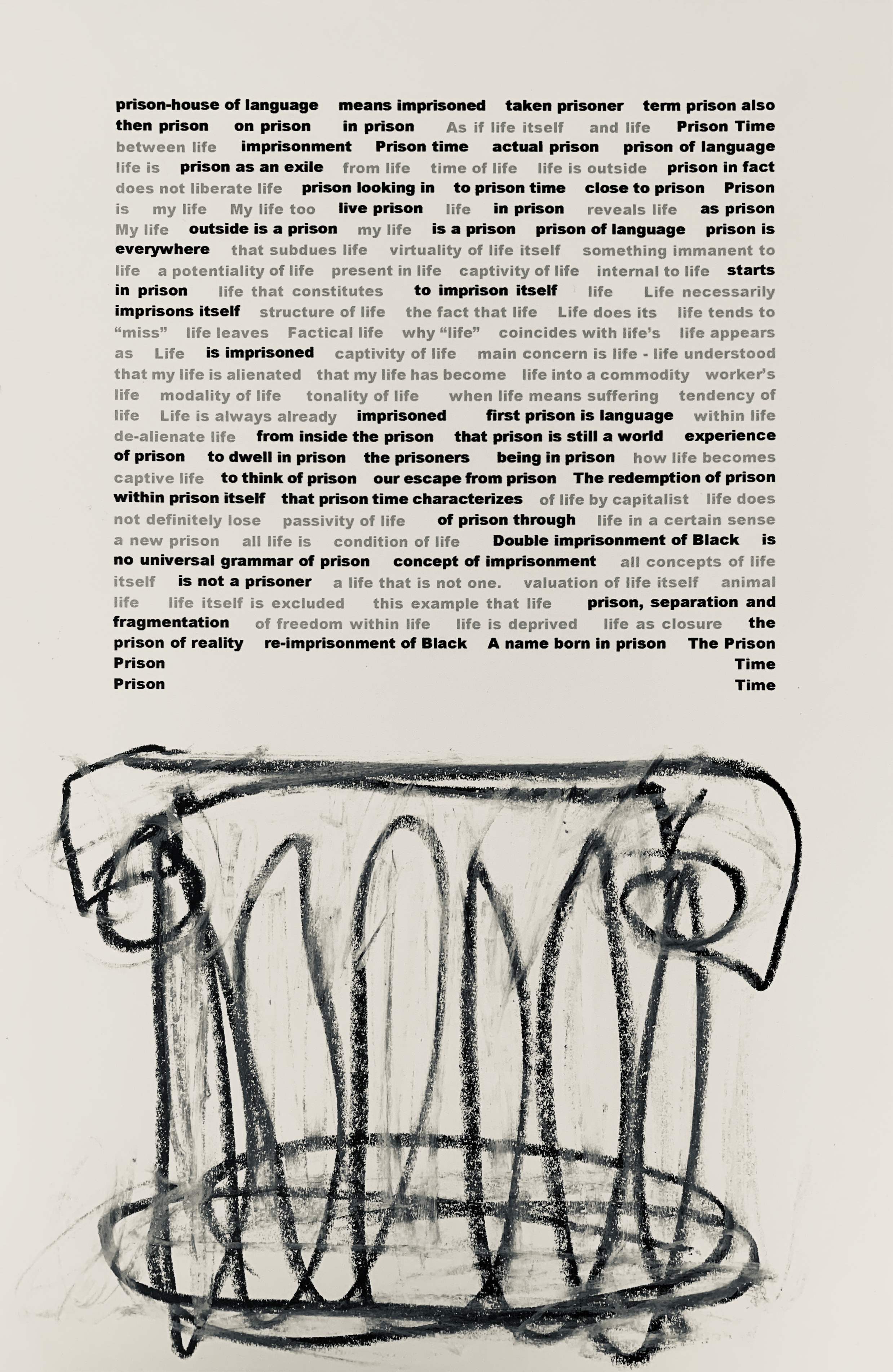

Cf. Frederic Jameson, The Prison-House of Language: A Critical Account of Structuralism and Russian Formalism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975).

“Prison,” Centre National de Ressources Textuelles et Lexicales, 2012, ➝.

Michael Hardt, “Prison Time”, in Yale French Studies, “Genet: In the Language of the Enemy,” special issue 91 (1997): 64–79.

Ibid., 66.

Ibid., 66–67.

“Stereotypic behaviour is an abnormal behaviour frequently seen in laboratory primates. It is considered an indication of poor psychological well-being in these animals. It is seen in captive animals but not in wild animals…Stereotypic behaviour has been defined as a repetitive, invariant behaviour pattern with no obvious goal or function. A wide range of animals, from canaries to polar bears to humans can exhibit stereotypes. Many different kinds of stereotyped behaviours have been defined and examined. Examples include crib-biting and wind-sucking in horses, eye-rolling in veal calves, sham-chewing in pigs, and jumping in bank voles. Stereotypes may be oral or involve bizarre postures or prolonged locomotion. A good example of stereotyped behaviour is pacing. This term is used to describe an animal walking in a distinct, unchanging pattern within its cage…The locomotion may be combined with other actions, such as a head toss at the corners of the cage, or the animal rearing onto its hind feet at some point in the circuit.” Nora Philbin, “Towards an understanding of stereotypic behaviour in laboratory macaques,” Animal Technology: Journal of the Institute of Animal Technicians 49, no. 1 (1998): 19–33.

Barthes, “Inaugural Lecture,” 368.

Martin Heidegger, Phenomenological Interpretations of Aristotle, trans. Richard Rojcewicz (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001), 80.

Michel Henry, Marx: A Philosophy of Human Reality, trans. Kathleen MacLaughlin (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993).

My translation. Ibid., 608.

Hardt, “Prison Time,” 67–68.

Ibid., 68.

Ibid.

Ibid., 64.

Ibid., 70.

Ibid., 68.

Barthes, “Inaugural Lecture,” 369.

Michael Hardt and Tony Negri, Empire (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000), 61–62.

Martin Luther King, Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Birmingham City Jail, April 16, 1963.

Frank B. Wilderson, Red, White & Black: Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonisms (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2010).

Ibid., 279.

Ibid.

Ibid., 281.

Ibid., 288.

An earlier version of the text was published by Alienoscene on October 23, 2018. It is the edited transcript of a lecture given at the European Graduate School on August 13, 2018.