Rooms of Muted Violence

April 25–June 9, 2024

Oldenburg D-26121

Germany

Hours: Tuesday–Friday 2–6pm

Saturday–Sunday 11am–6pm

T +49 441 2353208

info@hausmedienkunst.de

Rooms of Muted Violence is a solo exhibition by the Dutch artist Robert Glas, whose research-based works revolve around the question of bureaucratically produced justice. With his films and film installations, he aims to open up spaces to scrutinize the ways bureaucracies produce justice, interrogate the kind of justice they produce, and tackle the question of at whose gain and whose cost. Following anthropologist David Graeber’s line of thought, Glas is convinced that, next to politics, it is actually bureaucracy that is the true organizing force of modern society. Through his works, the artist aims to make visible the willful blindness—which bureaucracy itself produces—toward the violence inherent in its system.

The exhibition’s central piece is the video installation 1986, Or a Sphinx’s Interior (2022), which takes as its starting point the notable expansion in the prison system from the 1980s onward throughout the Western world. The urgency of Glas’s artistic inquiry stems from the fact that decades-long abolitionist practices in the Netherlands, building support until the mid-1980s, stand in stark contrast with today’s virtually uncontested call for harsher punishments. Meanwhile, in the field of philosophy, mainly inspired by recent neuroscience research, the existence of free will is being challenged yet again.

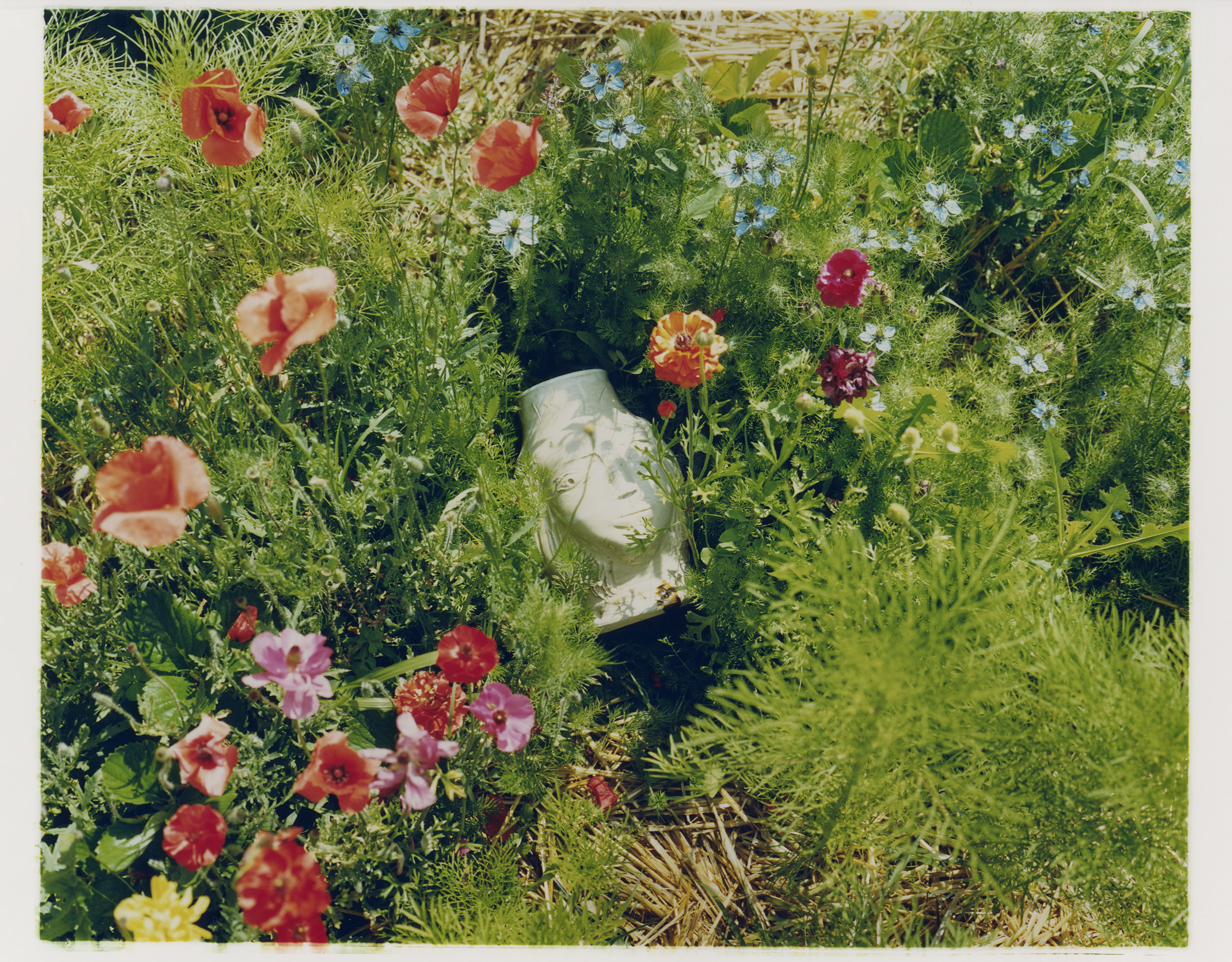

For Sphinx, Glas rather ambitiously chose to reproduce, at 1:1 scale, the architectural model of a Rotterdam prison cell, which stands in the middle of the exhibition hall. The original was built by the renowned Dutch architect Carel Weeber in 1986 as part of his design process. Working with actor Ali Ben Horsting (in the role of the architect’s younger self), the former prison detainee Jonathan Geerman, and Weeber himself, Glas created a video work examining the architect’s visit to his test model in the 1980s. The initial practical question of “How does one test a prison cell?” leads to underlying questions about how incarceration affects a life and a body.

Alongside Sphinx, the exhibition includes 1986, Or Recalling Louk Hulsman (2024), which circles around the legacy of the well-known professor of criminal law (until 1986), who toward the end of his career passionately advocated for abolishing the criminal justice system. The artist brings together five criminal law students with five fellow Rotterdammers who have spent time in prison. While reciting some of Hulsman’s crucial texts, the law students—trained in public speaking—were asked to assist the former inmates in practicing a persuasive performance. During rehearsals, conversations arose about the relevance of Hulsman’s propositions and insider perspectives from today’s context, marked by politicized calls for increasingly harsher punishments while critical voices struggle to be heard.

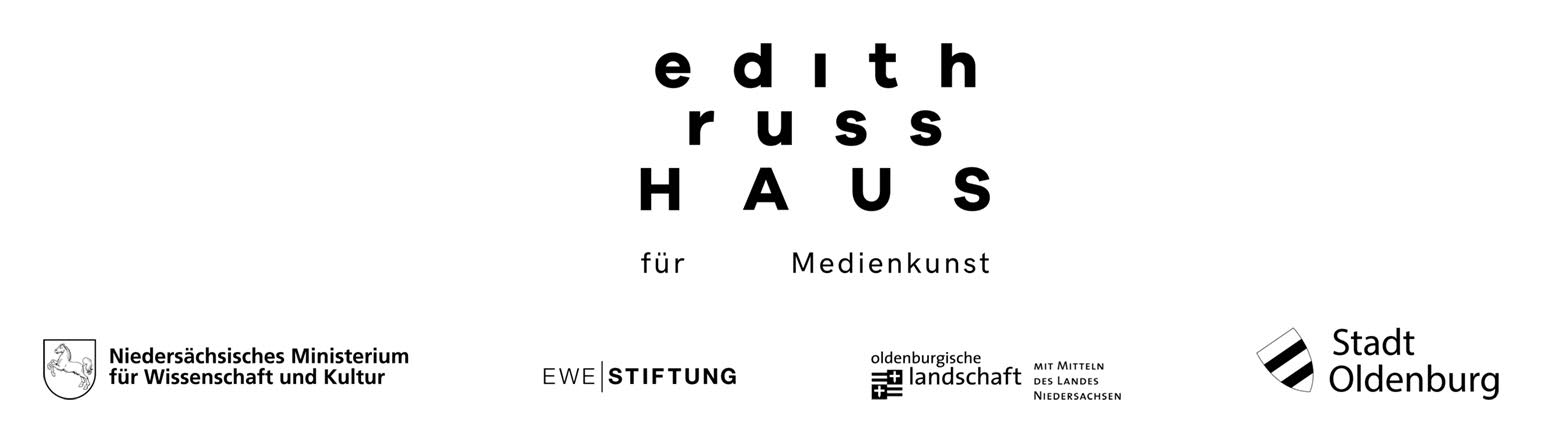

The work Voor vrij Nederland (For a Liberated Netherlands) (2016), involves an actual legal battle the artist took on. It comprises a series of photographs and all documents produced in the process of taking the State of the Netherlands to court regarding the right to access of state facilities in order to photograph them. The photos depict the interiors of detention centers for asylum seekers with rejected application—a policy that became the target of international criticism. To exhibit these images, the artist had to engage in a second lawsuit to claim the right to distribute them, supported by lawyer Frans Willem Verbaas, Amnesty International, and the Dutch Journalists Union. The small marks left behind in the spaces—like finger scratches and nose prints on windows—create portraits of people who are, to this day, detained as criminals without having committed a crime.

How to Motivate Someone to Leave Voluntarily, also from 2016, feels like a video portrait of such a person. In this video documentation of an improvised performance, two actors and a coach in “motivational interviewing” reconstruct a dialogue between a “foreign national” and a “departure supervisor.” Motivational interviewing is a governmental tactic intended to manipulate a person into believing they are leaving a country of their own will—a method in use in the Netherlands since 2016.

Glas’s solo exhibition is completed with a newly curated selection of books, under the title If Luck Swallows Everything (for Justizvollzugsanstalt Oldenburg Niedersachsen). The set of books was gifted by the artists ands is located in the nearest prison, Justizvollzugsanstalt Oldenburg, and a copy of the library is available for reading in the exhibition space. The books all focus on free will, with authors ranging from free will defenders such as Daniel Dennett to fierce free will skeptics like Derk Pereboom.

Why is free will particularly significant in this context? Retribution—or simply, payback—is a key component of prison sentences. Through this component, the state, on behalf of the victim and society as a whole, avenges the crimes a convict is found guilty of. A guilty sentence requires that it be proven the suspect committed the crimes they are charged with and, critically, that they could have acted otherwise. The assumption that humans have free will is thus fundamental to the criminal justice system. As a philosophical concept, however, free will is far from uncontested and the subject of millennia-old debates.

The works in Rooms of Muted Violence, based on extensive research into both the justice and European asylum systems, share a calm and contemplative tone. The artist instrumentalizes conversation as a primary tool in tackling major political, ideological, and societal questions, unfolding from his interest in the possibilities of using a common language to move beyond the communication breakdown between the formalized world of bureaucratic justice and the world of everyday life.