June 18, 2021–January 9, 2022

Berlin 10117

Germany

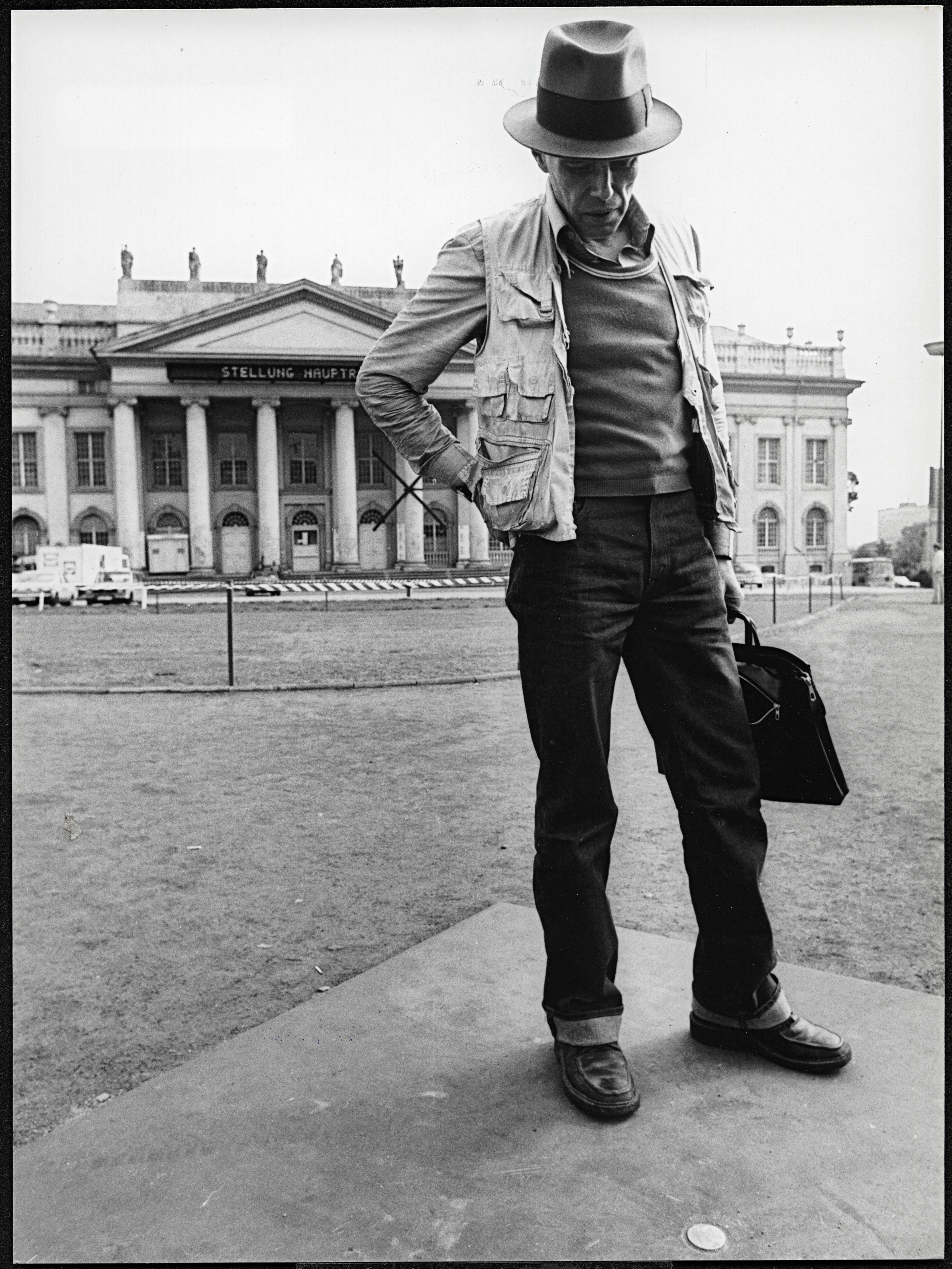

From its founding in 1955, this major, internationally oriented exhibition acted as a place where West German self-understanding was debated. From that time on, the organisers have felt empowered every four, later every five, years to represent current artistic tendencies. For the first time, the Deutsches Historisches Museum places the history of the first ten documenta exhibitions in the context of the political, cultural- and social-historical development of the Federal Republic of Germany between 1955 and 1997. Artworks, films, documents, posters, oral history interviews and other original cultural-historical exponents illustrate how the documenta as a cultural event and at the same time as a historical location commented on, called for, and reflected on socio-political changes. Famous documenta works by such artists as Max Beckmann, Willi Baumeister, Joseph Beuys, the Guerrilla Girls, Hans Haacke, Séraphine Louis, Wolfgang Mattheuer, Emy Roeder and Fritz Winter are shown in the exhibition.

Beginning in 1955, the documenta audience was confronted with “Modern Art,” artistic styles which until 1945 had been considered “degenerate” in Germany. The programme with which the Federal Republic commended itself in Kassel to its Western partners lived off a past it purported to want to overcome. And yet almost half of those who participated in the organisation of the first documenta had been members of the NSDAP, the SA, or the SS. By contrast, works by murdered Jewish or persecuted communist artists were not represented at the documenta. There was apparently no room for the victims of persecution, war and mass murder in the narrative of the supposed “fresh start” in the young Federal Republic.

documenta was closely connected with the political agenda of the Federal Republic of the 1950s and 1960s and mirrored the stress and strain of the Cold War. The formerly defamed Modern Art advanced, due to considerable financial support and commissioning by the political entities, to the status of official state art and thus a means of bonding with the “West.” Located on the periphery of the Eastern zone, it also addressed itself to an East German audience, but East German art was not welcome. It was not until the 1970s, in the wake of Willy Brandt’s “Ostpolitik,” that the documenta showed awareness of East German and Eastern European artists.

Over the years, the documenta forged its career as a festive, international, major event, thronged with young people who came there to discuss art with the artists. However, the traditional educated middle-class milieu reacted to the event with irritation, sometimes even holding counterdemonstrations. But in the following decades, the brand name “documenta” established itself once and for all international as the model of a popular and commercially oriented art event in a globalised (art) world. Time and again it became a platform for political activism, as the feminist artists’ group Guerrilla Girls impressively demonstrated at documenta 8 in 1987.