October 15, 2020–January 23, 2021

17 West 17th Street

10011 New York NY

On view by appointment, RSVP is required, Wednesday–Saturday 11am–6pm

The Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation is pleased to present To Cast Too Bold A Shadow, an exhibition examining culturally entrenched forms of misogyny in order to understand the dynamics between sexism, gender, and feminism. Artists Anetta Mona Chisa & Lucia Tkáčová, Furen Dai, Tracy Emin, Hackney Flashers, Rajkamal Kahlon, Joiri Minaya, Yoko Ono, Maria D. Rapicavoli, Aliza Shvarts, Betty Tompkins, and Mierle Laderman Ukeles challenge the constraints women have endured across economic, cultural, and political lines.

The title borrows a line from Adrienne Rich’s 1963 poem “Snapshots of a Daughter-In-Law,” suggesting that ‘to cast too bold a shadow’ is not only a right, but a necessity, and that gender equality is critical in forming a more just society. Rajkamal Kahlon’s series Do You Know Our Names? (2017) questions the representation of colonial subjects in visual culture, and humanizes those who have been reduced to nameless anthropological subjects. Joiri Minaya complicates the fetishization of ‘the other’ through her #dominicanwomengooglesearch(2016). Culling images from the web of the phrase “Dominican women,” she examines the destructive effects culturally specific fantasies have had on women, specifically those from the developing world.

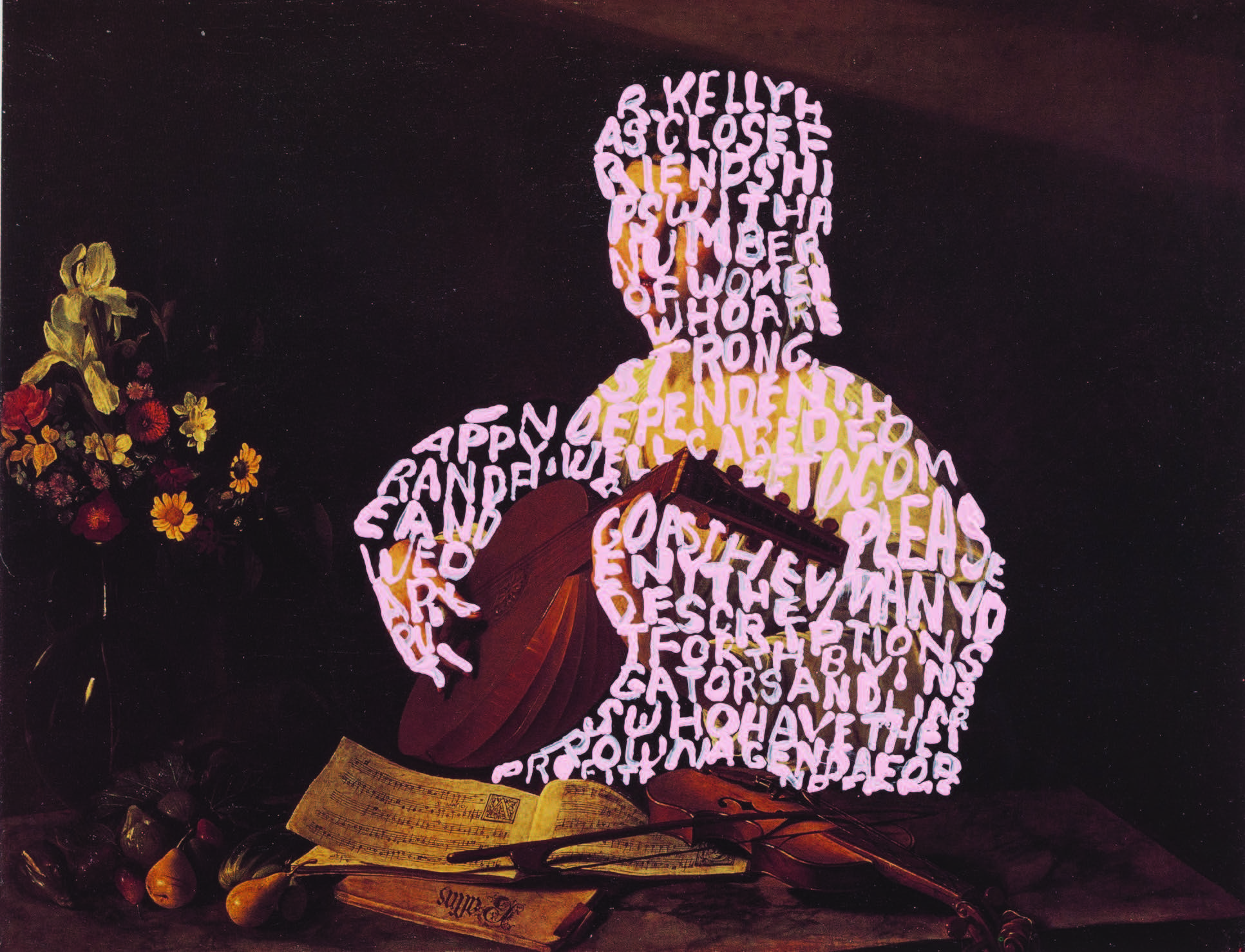

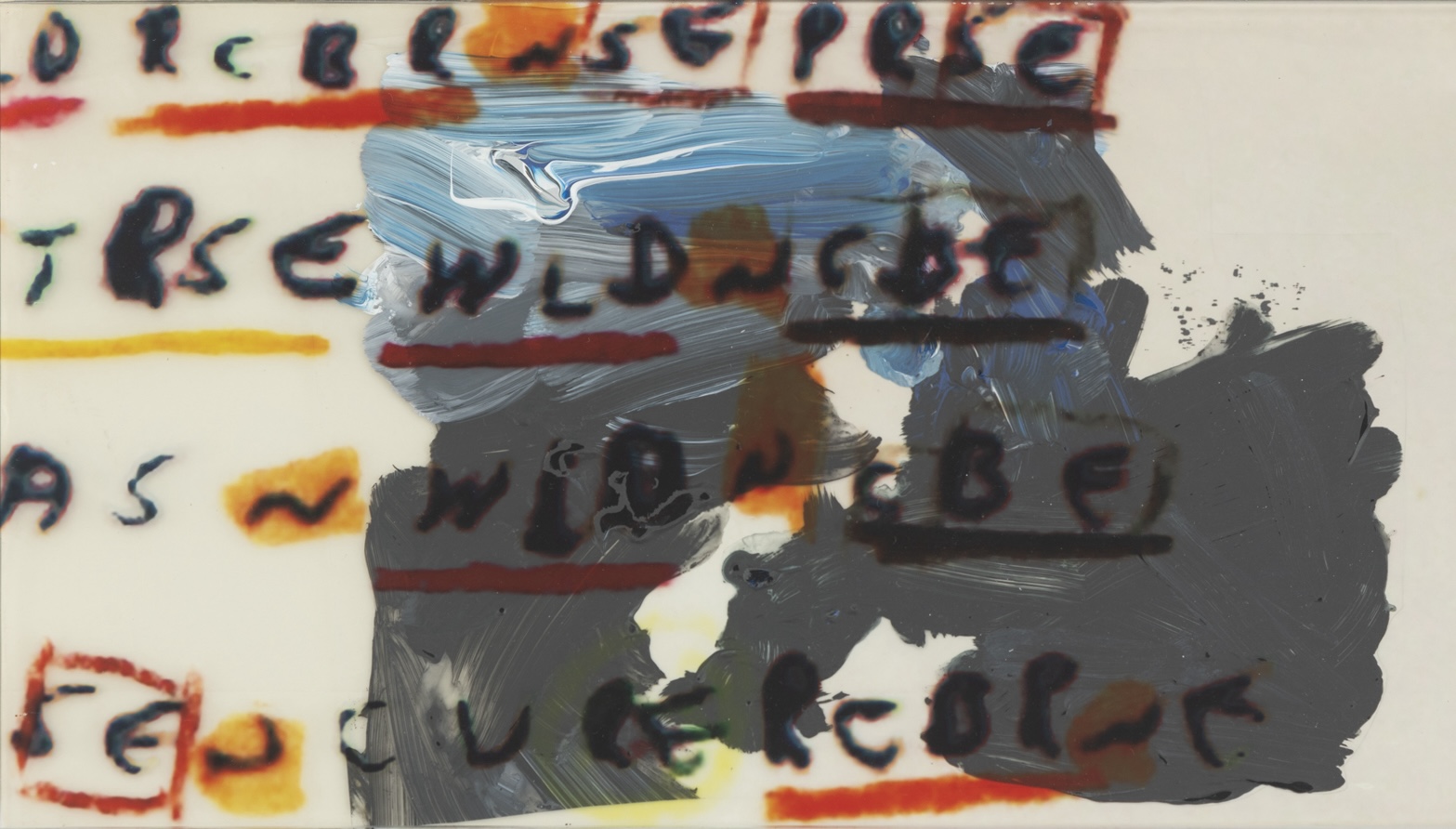

The place of desire–specifically in a patriarchal society–is analyzed by Tracey Emin, Yoko Ono, and Betty Tompkins. In her 1995 video Why I Never Became a Dancer, Emin unpacks the misogyny she experienced as a teenager, when she learned the double standard for women, in regards to their sexual adventures. Yoko Ono’s participatory performance Cut Piece (1964/2003) invited audience members to cut off a piece of her clothing, which they could then keep. Ono’s rules gave her the right to end the performance when she saw fit, ensuring that she maintained agency, and the participant was forced to confront the implications of the potential for gender-based violence in everyday life. In response to violence against women, Betty Tompkins addresses the hollow apologies made by male celebrities who have been called out for sexual assault in the context of the #MeToo movement. Pages torn from art history books provide backdrops for her interventions which partly obscure classical paintings with the text quoting their statements of regret.

In a newly commissioned installation Anatomy (2020), Aliza Shvarts classifies illustrations collected from rape evidence kits utilized by different law enforcement agencies throughout the United States. Used to document violence endured by survivors of sexual assault, Shvarts isolates the imagery of these anatomical diagrams to question how survivors of assault are often oppressed through a lack of nuance in both policy and practice.

The apparatus of motherhood and marriage are critiqued by several artists. In Love for Sale (2020), Furen Dai transcribes verbal exchanges between parents in marriage markets in Beijing, highlighting the gender imbalances in Chinese culture. Maria D. Rapicavoli’s newly commissioned film The Other: A Familiar Story(2020) reconstructs the narrative of an Italian woman, forced to marry and emigrate to the United States from Italy after World War II. Rapicavoli’s project is supported by the Italian Council program (6th Edition, 2019), to promote Italian contemporary art internationally, funded by the Directorate-General for Contemporary Creativity of the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism.

Hackney Flashers (1974–80) staged Who’s Still Holding the Baby? (1978) as a critique of the lack of state support for child care, and its impact on the opportunities for economic and educational advancement of women. Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ Washing/Tracks/Maintenance: Outside, July 22, 1973, staged at the Wadsworth Athenaeum, ritualized the hidden menial work that underscores institutions. Artist duo Anetta Mona Chisa & Lucia Tkáčova’s photograph Caryatids, (2013) features female models standing in for the mythological figures that uphold the entablature of a building. The figures balance precariously on stacks of books, drawing a connection between institutional power and knowledge, emphasizing the importance of what women know.