Grand Hotel Abyss

steirischer herbst '19

September 20–November 28, 2019

Graz 8010

Austria

Hours: Tuesday–Sunday 10am–6pm

T +43 316 740084

info@halle-fuer-kunst.at

In the frame of the extensive project Grand Hotel Abyss, the festival steirischer herbst and the Künstlerhaus, Halle für Kunst & Medien collaborate on three artistic positions whose works "play" with the idea that the construction of the Künstlerhaus was a farewell present by the British allies positioned in Styria in the post-war era. This rumor sheds new light on the genesis of the institution and its late modern building that was changefully planned over decades and eventually realized in 1952, under the auspices of the province of Styria and with the support of the city of Graz, the federacy and local artists. For the construction of the 2nd republic, the British allies put significant emphasis, next to general administrative activities, on the rebuilding of the constitutional state, the re-democratization and denazification, whereby a cosmopolitan cultural policy played a valuable accompanying role, which provided the regional population and artists with access to modernism, which was prohibited in the times of Austro-fascism and National Socialism, and enabled international exchange.

Jasmina Cibic’s video installation The Gift—Act I (2019) is the first chapter of her new poetic study of the many “political gifts” found in European history of art and architecture, especially during times of rebuilding after political upheaval. There is a persistent and unsubstantiated rumor in Graz that the Künstlerhaus was also such a “gift” from the departing British occupation forces. Cibic’s installation looks at how culture turns into a Trojan horse with such donations. Some of the most spectacular architectural examples of this become the backdrop for a poetic narrative guided by “Four Fundamental Freedoms”—allegorical characters based on a speech by Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1941. These protagonists devise a plan for a cultural battle between different worldviews, where three personifications of Art, Architecture, and Music face off to tender themselves as the perfect presents for an imaginary, divided nation. They are judged by the Freedoms, who offer increasingly aggressive populist criticisms of culture’s complicity to politics, and in the end, their verdict is damning. Cibic’s film follows this contest, while a wrought metal sculpture represents the perfect gift with a quote drawn from the political debates around one of the film’s locations: “Everything that you desire and nothing that you fear.”

Jeremy Deller’s new single-channel film Putin’s Happy (2019) provides a unique view of the rise of right-wing populism and, possibly, fascism in the United Kingdom. It looks at the often-absurd xenophobia, isolationism, and misplaced patriotism fueling the vote to leave the European Union, sentiments ironically shared by many Continental Europeans on the right, including those in Austria. A vocal opponent of Brexit, Deller has intervened directly in the political process—as with his highly publicized T-shirt campaign of 2017—and also delved into the “magic” of British national myths and political history that have produced the present moment. In his new film, Deller focuses on the grotesque details and eccentric decor of British populism’s fantasy world, showing its tragicomic effects in reality as its protesters reappear day in and day out. Anti-Brexit banners designed by Deller preface the installation, continuing another means with which Deller has lent his unique voice as an artist to political struggles over the years.

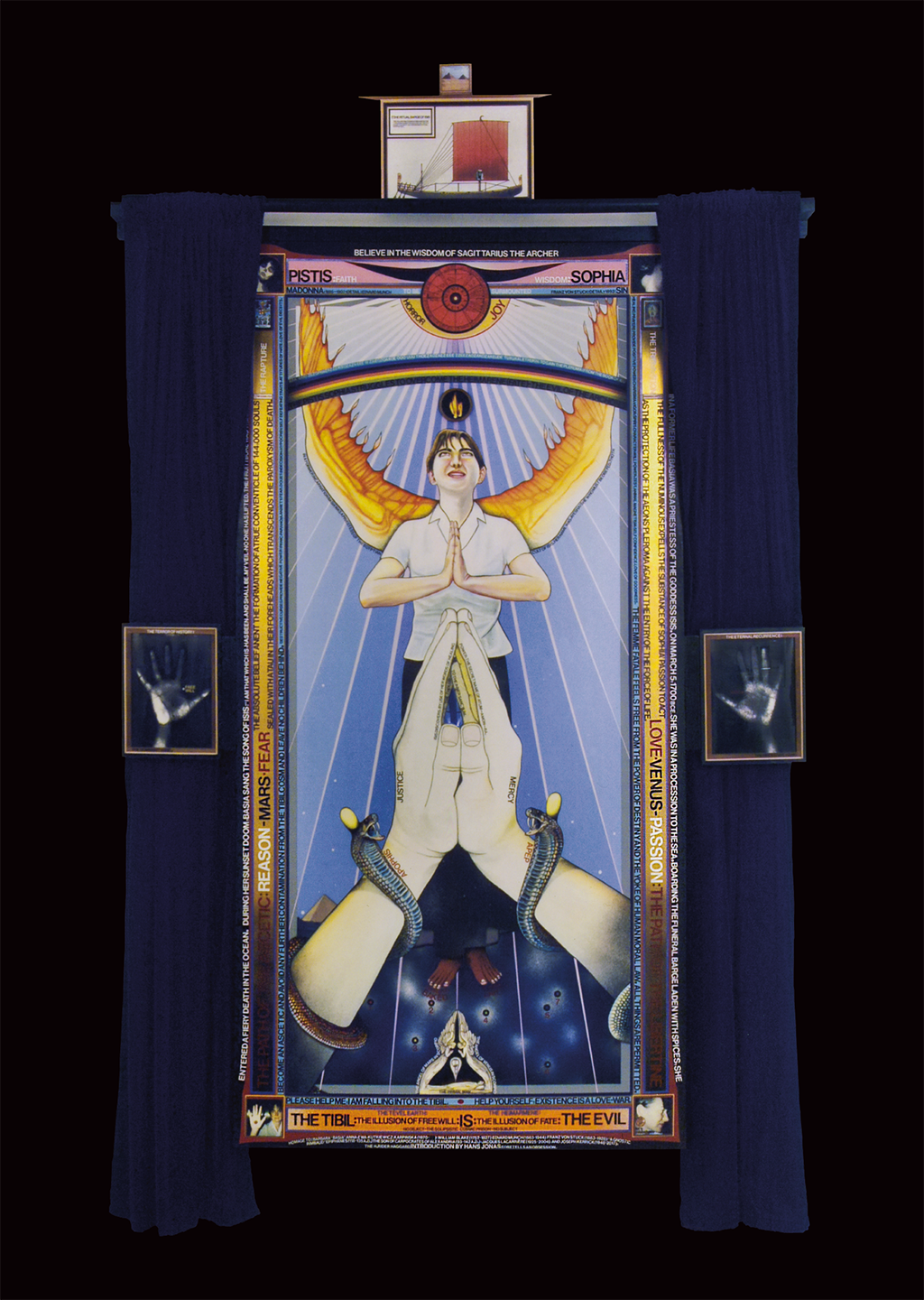

Ian Hamilton Finlay’s work, presented here through a selection of prints, objects, and aphorisms (1973-2003), revolves around the ambivalence of neoclassicism—a style linked to the democratic ideals of the French Revolution but revived as a totalitarian aesthetic in the 20th century. Finlay daringly balances on this double edge. Fragments of neoclassical art become visual puns, commented by lines of poetry, inscriptions, and anagrams, reflecting upon the history of the revolution and its conscription of classical art to quasi-military service. Not only does Finlay find traces of this militarization in neoclassicism itself, he also discovers neoclassical elements in the aesthetically beautiful machines and camouflage patterns of modern war. Finlay rarely traveled and spent most of his life working on a garden installation in Scotland facetiously named Little Sparta to contrast it with nearby Edinburgh, which is sometimes called “Athens of the North” due to its topography and its high incidence of neoclassical architecture. It was here that he realized many of the poetic propositions shown in these prints, punctuating his rambling garden with stone tablets on trees, classical fragments, aircraft-carrier bird platforms, and beehive battleships. In the present context, the outward conservatism and defiant radicalism of his work comments on the urban myth that Graz’s Künstlerhaus was a gift from the British occupation forces.

The exhibition is accompanied by an extensive educational and side program, which can also be accessed through the institution’s online magazine, the KM– Journal and the festival’s Vorherbst Magazine.

Curators: Ekaterina Degot, Christoph Platz, David Riff